The home-buying struggles of Americans, particularly millennials, have been well documented. Yet a recent study by Hunt.com found that the often-proposed “solution” of renting is not much of a panacea. Rents as a percentage of income, according to Zillow, are now at a historic high of 29.1%, compared with the 25.8% rate that prevailed from 1985 to 2000.

No surprise, then, that 58% of the 1,300 renters in the Hunt survey said they felt “stressed” about their rent, or that many respondents said they couldn’t save for future purchases like homes. Rather than the sunny freedom promised by those who promote a “rentership society,” most of those surveyed said that finding a convenient place with the amenities they required – for example, fitness rooms, places for pets and adequate space – was very difficult. Some renters have been forced to euthanize their pets, spend upwards of 50 days looking for a place or move farther from family and friends.

All of this is taking place at a time when the national vacancy rate has fallen to 7.3% (in the second quarter of 2017), from 11.1% in the third quarter of 2009. That trend has continued even with apartment construction in many areas, notably core cities, because the new buildings tend to be too expensive for most renters.

Fuel for a Housing Crisis

There is a strong relationship between high rents and high house prices. Although rents have not risen as much as house prices generally, they tend to attract people who in the past might have become homeowners but instead have been crowded out by the high prices. This essentially brings into the rental market more affluent tenants who directly compete with those with lower incomes.

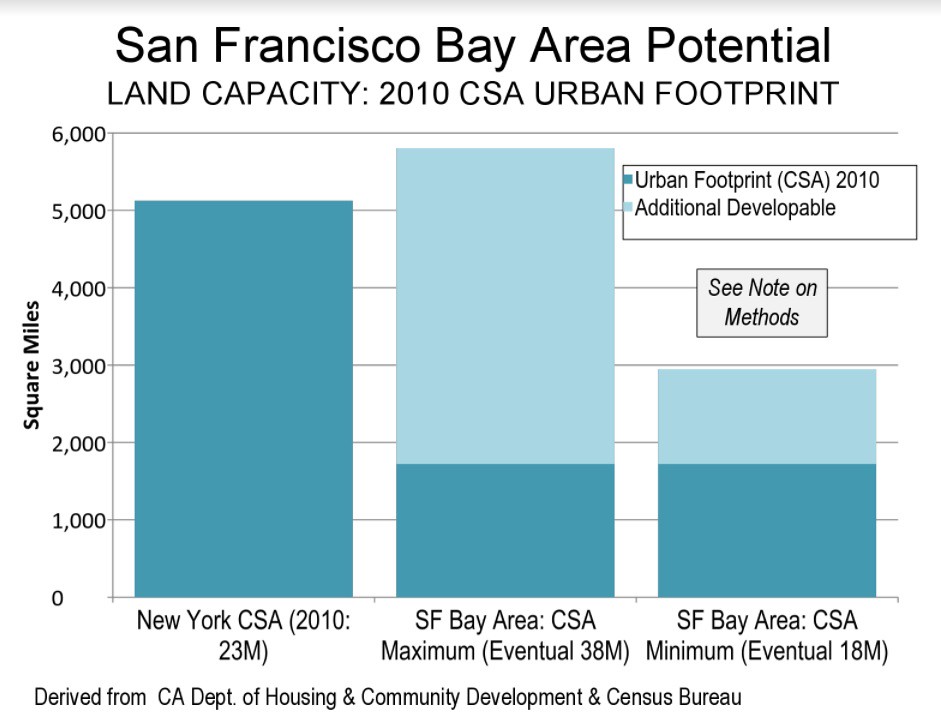

The result in many places, such as Southern California, is overcrowding. Two-thirds of the places in the United States (municipalities and census-designated places) with more than 5,000 residences and with more than 10% of housing units being overcrowded are in California, according to the American Community Survey.

The rent-related stress also points to a bigger crisis: the decline in the purchase of homes. One of the most prominent reasons for not buying a house directly relates to higher rents: It becomes all but impossible to save enough for a down payment. This also reflects changes in the labor market; service and blue-collar workers, whose incomes have been down in relation to rents, are the most burdened by rising rents. In San Francisco, even a teacher has been driven into the ranks of the homeless.

The situation is worst in the most expensive markets. In New York City, incomes for millennials (ages 18–29) have dropped in real terms compared with the same age cohort in 2000, despite considerably higher education levels, while rents have increased 75%. New York, Los Angeles and San Francisco have three of the nation’s four lowest homeownership rates for young people and among the lowest birthrates.

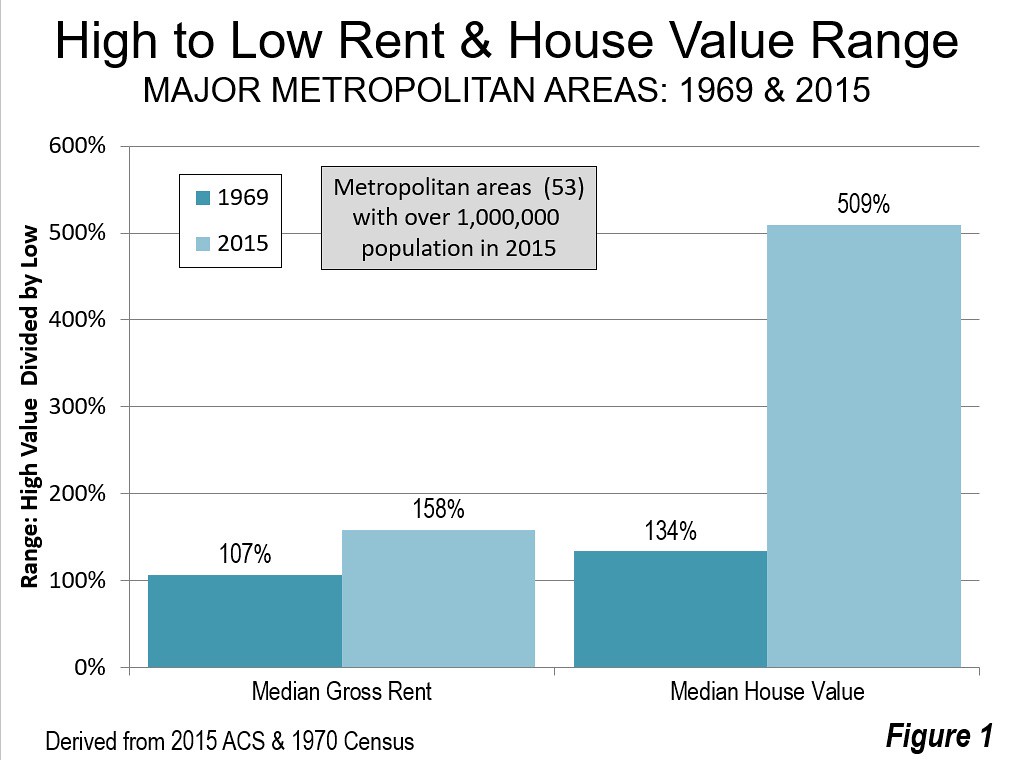

According to Zillow, for workers ages 22-34, rent costs claim up to 45% of income in the Los Angeles, San Francisco, New York and Miami metropolitan areas, compared with closer to 30% of income in metros like Dallas-Fort Worth and Houston. Home prices provide an even starker contrast. Dallas-Fort Worth, the nation’s fastest-growing housing market, as well as Houston, San Antonio and Charlotte have prices that are more like one-third those of the superstars.

That helps explain why, according to the Hunt survey, the highest percentage of people who cannot save for future purchases (almost 60%) live on the pricey West Coast. The West Coast also had the largest percentage of people stressed about their rent, followed, not surprisingly, by the East Coast.

High rents may also help explain recent shifts in migration to lower-rent areas. A recent survey by Apartmentalist.com found that the best prospects for renters becoming homeowners are in metropolitan areas like Pittsburgh, Provo, Madison, San Antonio, Columbus, Oklahoma City and Houston; the worst are, not surprisingly, in California, New York, Boston and Miami.

Profound Implications

What emerges from the Hunt study, and other research, is a renting population that may never achieve homeownership. This represents a sort of social evolution from the culture of self-assertion and independence that once so clearly characterized America after World War II and was so important to the unprecedented spread of middle-income affluence. Rather than striking out on their own, many millennials are simply failing to launch, with record numbers living with their parents or forced to shell out much of their income rent.

The implications of high rent, and declining home ownership, could be profound over time. In survey after survey, a clear majority of millennials — roughly 80%, including the vast majority of renters — express interest in acquiring a home of their own. A Fannie Mae survey of people under 40 found that nearly 80% of renters thought that owning made more financial sense, a sentiment shared by an even larger number of owners. They cited such things as asset appreciation, control over the living environment and a hedge against rent increases.

But it won’t just be renters impacted by rising rents. Jason Furman, who served as chairman of the Council of Economic Advisors under President Obama, calculated that a single-family home contributed two and a half times as much to the national GDP as an apartment unit.

The decline in investment in residential properties has dropped to levels not seen since World War II. By some estimates, if we had that kind of housing investment again, we would return to 4% growth, as opposed to our all-too-familiar 2% and below.

America’s housing crisis, long tied to ownership, is now extending into rising rents. But the stress that renters are feeling impacts all of us.

This piece originally appeared on Forbes.com.

Joel Kotkin is executive editor of NewGeography.com. He is the Roger Hobbs Distinguished Fellow in Urban Studies at Chapman University and executive director of the Houston-based Center for Opportunity Urbanism. His newest book is The Human City: Urbanism for the rest of us. He is also author of The New Class Conflict, The City: A Global History, and The Next Hundred Million: America in 2050. He lives in Orange County, CA.

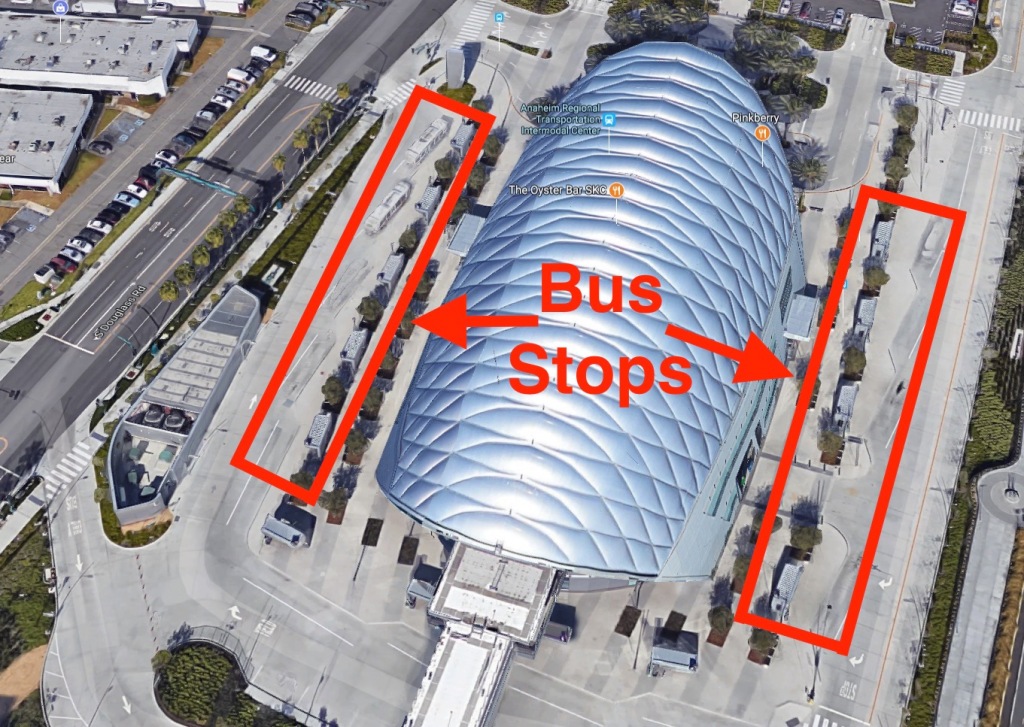

Wendell Cox is principal of Demographia, an international public policy and demographics firm. He is a Senior Fellow of the Center for Opportunity Urbanism (US), Senior Fellow for Housing Affordability and Municipal Policy for the Frontier Centre for Public Policy (Canada), and a member of the Board of Advisors of the Center for Demographics and Policy at Chapman University (California). He is co-author of the “Demographia International Housing Affordability Survey” and author of “Demographia World Urban Areas” and “War on the Dream: How Anti-Sprawl Policy Threatens the Quality of Life.” He was appointed to three terms on the Los Angeles County Transportation Commission, where he served with the leading city and county leadership as the only non-elected member. He served as a visiting professor at the Conservatoire National des Arts et Metiers, a national university in Paris.

Photo: Omar Bárcena, via Flickr, using CC License.

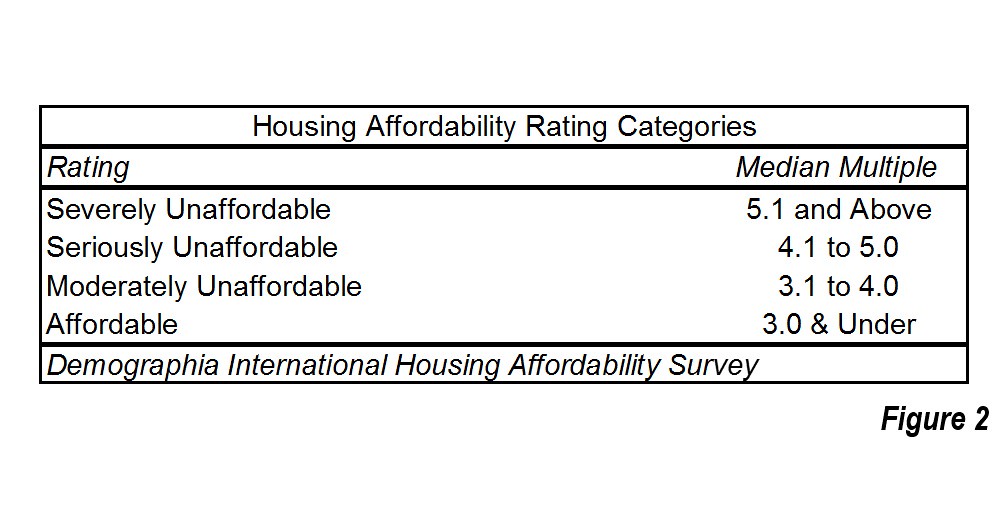

Demographia International Housing Affordability Survey with a median multiple of 9.6 (median house price divided by median household income) and the San Francisco metropolitan area is 7th worst, with a median multiple of 9.2. Before the evolution toward urban containment policies began, the median multiples in these metropolitan areas (and virtually all in the United States) were around 3.0 or less.

Demographia International Housing Affordability Survey with a median multiple of 9.6 (median house price divided by median household income) and the San Francisco metropolitan area is 7th worst, with a median multiple of 9.2. Before the evolution toward urban containment policies began, the median multiples in these metropolitan areas (and virtually all in the United States) were around 3.0 or less.