United States Secretary of Transportation Ray LaHood and Washington Post columnist George Will have been locked in debate over transit. Will called LaHood the “Secretary of Behavior Modification” for his policies intended to reduce car use, citing Portland’s strong transit and land use planning measures as a model for the nation. In turn, the Secretary defended the policies in a National Press Club speech and “upped the ante” by suggesting the policies are “a way to coerce people out of their cars.”

These are just the latest in a series of media accounts about Portland, usually claiming success for its policies that have favored transit over highway projects as well as its “progressive” land use policies. Portland has also become the poster child for those who advocate planning restrictions and subsidies favoring higher density development in parts of the urban core.

Indeed if Secretary LaHood has his way, Portland could become The Model for federal transportation policy. So perhaps it is appropriate to review what it has accomplished.

Portland’s Mediocre Results

Portland’s record of transit emphasis began more than 30 years ago, when the area “traded in” federal money that was available to build an east side freeway to build its first light rail line. The east side light rail opened in 1986. Since that time, Portland has significantly increased its transit service, especially opening three more light rail lines (West Side, North Side and Airport) as well as a downtown “streetcar.”

Portland’s Static Transit Market Share: With these new lines and expanded service, Portland has experienced a substantial increase in transit ridership. Passenger miles have increased more than 130 percent since 1985, the last year before the first light rail line was opened. This is an impressive figure.

However, over the same period, automobile use increased just as impressively. In 1985, approximately 2.1 percent of motorized travel in the Portland urban area was on transit and it remained 2.1 percent in 2007, the latest year for which data is available.

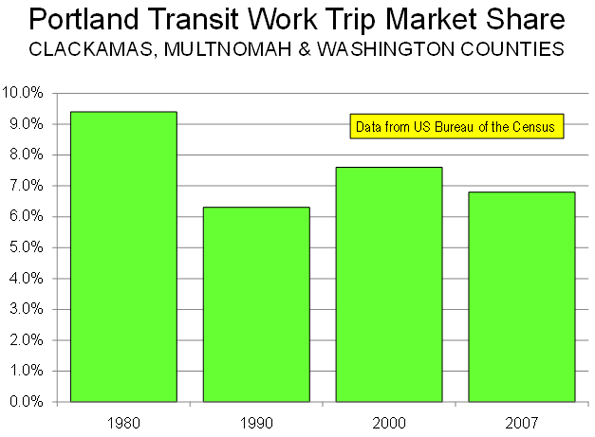

Portland’s Declining Transit Work Trip Market Share: One of transit’s two most important contributions to a community is providing an alternative to the automobile for the work trip (the other important contribution is mobility for low income citizens). Work trip rider attraction is important because much of this travel is during peak periods, when roadways are operating at or above full capacity. In 1980, the last year for which data is available before the first light rail line opened, United States Bureau of the Census data indicates that transit’s work trip market share was 9.5 percent in the Portland area counties of Clackamas, Multnomah and Washington covered by Portland’s strong land use policies. Yet despite this, and the transit improvements, the work trip market share has not grown. By 1990, transit’s market share had dropped a third, to 6.3 percent. It rose to 7.6 percent in 2000 and by 2007 had fallen back to 6.8, despite opening two new light rail lines since 2000 (Figure 1). Remarkably, transit’s 2007 work market share was 28 percent behind its 1980 share and had fallen 10 percent since 2000.

Figure 1:

Yes, Portland did increase its transit use, but failed to increase the share of travel on transit and the proportion of people riding transit to work declined.

Driving the Portland Evangelism: GHG Emissions

Secretary LaHood’s affection for Portland appears to principally be that its policies can materially assist in the objective of reducing greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. The data is available to test that claim.

We examined GHG emissions per capita by transit in Portland and the urban personal vehicle fleet, including cars and personal trucks (principally sport utility vehicles). Overall, including upstream emissions (such as refining and power production), transit in Portland is about 50 percent more GHG friendly per passenger mile than the 2007 vehicle fleet. If all of the increase in transit passenger miles from 1985 to 2007 replaced automobile passenger miles, then reduction of approximately 50,000 GHG tons can be said to have occurred as a result in 2007 (though as is indicated below, things are not that simple).

That sounds like a large number, until you consider that Portland traffic produces more than 8,000,000 GHG tons per year. Transit’s expansion has reduced GHG emissions by approximately 0.6 percent annually over 22 years. This pales in comparison to the 83 percent national reduction over a 45 year period that would be required by the Waxman-Markey bill being considered by Congress.

The Cost of GHG Emission Reduction

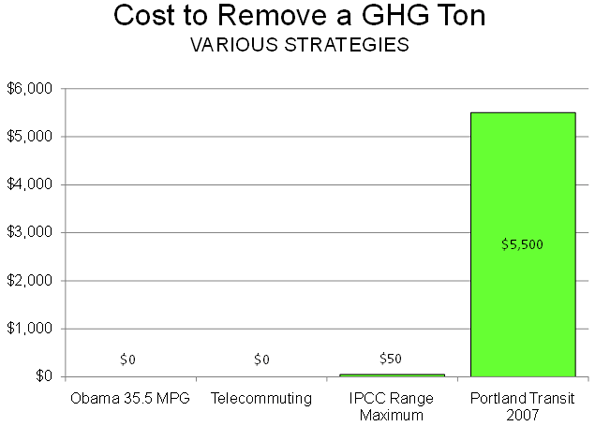

Moreover, GHG emission reduction requires a context. Not all GHG emission reduction strategies make sense. Given the widely held principle that GHG emission removal must not hobble the economy, it is crucial that costs (per ton of GHG removed) be a principal criteria. If excessively costly strategies are employed, the result will be wasted financial resources, which will translate into diminished economic growth and higher levels of poverty. According to the United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), between $20 and $50 per ton is the maximum amount necessary to accomplish deep reversal of CO2 concentrations between 2030 and 2050. It is fair to characterize any amount above $50 per ton as wasteful and likely to impose unnecessary economic disruption.

Even that cost may be high. The current “market rate” is about $14 per ton, which appears to approximate the amount that figures such as former vice-president Al Gore, Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi and California Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger pay to offset their GHG emissions from flying.

Portland Costs of GHG Emission Reduction

This $14 to $50 range provides the context for comparing the cost of GHG emission reduction through transit expansion in Portland. Annual transit costs in Portland more than tripled from 1985 to 2007 (including inflation adjusted operating costs and the annual capital costs of the light rail lines), an annual increase of more than $325 million. This figure is reduced to capture the consumer cost savings from reduced automobile gasoline and maintenance costs. The final result is a cost of approximately $5,500 per ton of GHG removed.

This is 110 times the IPCC $50 maximum and nearly 400 times the Gore-Pelosi-Schwarzenegger standard. If the United States were to spend as much to remove each ton of the likely 83 percent national reduction target, the cost would be $30 trillion annually, more than double the gross domestic product. To call the Portland GHG cost reduction figure extravagant would be an understatement.

Traffic Congestion Increases GHG Emissions

There is not a one-to-one relationship between reduced driving levels and reduced GHG emissions. As traffic congestion increases, urban travel speeds decline and “stop-and-start” traffic increases, fuel consumption is reduced (miles per gallon declines). Some or even all of the supposed gain from reduced driving can be negated by the higher GHGs from traveling in greater traffic congestion.

Portland’s traffic congestion has increased substantially since before light rail. Further, by 2007 Portland’s traffic congestion had become worse than average for a middle-sized urban area and worse than in much larger Dallas-Fort Worth, Atlanta, Philadelphia and Phoenix.

Further, according to information in the Texas Transportation Institute’s Annual Mobility Report, the amount of gasoline wasted due to peak period traffic congestion in Portland rose 18,000,000 gallons from 1985 to 2005 (latest data available, adjusted for the population increase), simply due to greater traffic congestion. The increase in GHG emissions from this excess fuel consumption is estimated to be approximately 200,000 tons annually. This is four times the estimated reduction in GHG emissions that was assumed to have occurred from the increase in transit ridership.

The bottom line: The Portland model inherently produces more congestion and increases GHG emissions. Failure to expand roadways to meet demand and forced densification increase traffic congestion.

Better Models

The ineffectiveness of Portland’s model strategies in GHG emission is in contrast to other strategies. Between 2000 and 2007, the share of people working at home in Portland rose more than one quarter. If transit and working at home should continue their 2000s rates, transit’s work trip share will be less than that of working at home by 2015. Working at home eliminates the work trip, resulting in substantial GHG emission reductions and does it at a cost of $0.00 per ton.

Another approach is the Obama Administration’s automobile fuel efficiency strategy. About the same time as the LaHood-Will debate was heating up, the President announced that automobile manufacturers would be required to increase their corporate average fuel efficiency for cars and light trucks to 35.5 miles per gallon by 2016, a 75 percent performance improvement from that of the present fleet. If this fuel efficiency could be achieved in Portland today, the reduction in GHG emissions would be more than 40 percent. This new policy would eventually close 90 percent of the gap between personal vehicles and transit in Portland.

President Obama indicated that this strategy is costless. The higher costs that consumers will pay for cars will be more than made up by the fuel cost savings. Thus, according to the President, this policy costs $0.00 per ton of GHG emissions removed, less than the IPCC’s $50 and less than Portland’s $5,500. Of course, it is not possible to achieve 35.5 miles per gallon now, but it will be (Figure 2).

Figure 2:

The best hybrid cars now achieve 50 miles per gallon, which makes them less GHG intensive than transit in Portland. President Obama has gone further, indicating the potential for developing 150 mile per gallon cars. The curtain could be rising on a future of cars that emit less GHG emissions per passenger mile than transit. People and officials genuinely concerned about GHG emissions should applaud these advances. On the other hand, people and officials who value coercive behavior modification more than GHG emission reduction are likely to resist.

The Consequences of Coercing People Out of Cars

Moreover, Portland policies ignore a crucial factor: how automobiles facilitate economic growth and employment. Generally, the research indicates that the economic performance of metropolitan areas is enhanced by greater mobility. Moreover, no transit system provides the extensive mobility made possible by the automobile, not in America and not even in Europe. Coercing people out of cars coerces some out of employment and into poverty.

Even where transit service is available, it generally takes longer than traveling by car. In 2007, travel to work by transit took 3:50 (three hours and 50 minutes) per week longer than driving in the nation’s largest metropolitan areas. With all of Portland’s transit improvements, it still takes approximately 3:15 longer per week to commute by transit than by driving. It appears that Secretary LaHood would add more than three hours (time many don’t have) to our work trip each week.

The Land Use Cost

The second plank of The Model is strong land use regulation (smart growth), which economic research shows to materially increase house costs, which would lead to a lower standard of living.

Time to Turn Off the Ideological Autopilot

The policies of The Model Portland have no serious potential for reducing GHG emissions and could even make it worse. On the other hand, the rapidly developing advances possible from improved vehicle technology, something the Administration espouses, show great promise. Behavior modification a la The Model turns out not only to be undesirable, but also unnecessary.

Wendell Cox is a Visiting Professor, Conservatoire National des Arts et Metiers, Paris. He was born in Los Angeles and was appointed to three terms on the Los Angeles County Transportation Commission by Mayor Tom Bradley. He is the author of “War on the Dream: How Anti-Sprawl Policy Threatens the Quality of Life.”

Comments

19 responses to “Portland: A Model for National Policy?”

Look, every half truthful study on this issue comes up with the following realities.

The true cost of running public transport is so high that if fares were “user pays”, nobody would use it.

The true cost can be calculated simply by dividing total running costs of public transport (just like a business would have to; not omitting the cost of financing infrastructure) by total fare revenue: then just multiply every fare by that factor.

If it is cheaper for a given traveller to run a given car rather than pay true-cost reflecting public transport fares, then that car uses less resources than public transport; not even counting the energy used to get to and from bus stops.

The cost benefit ratio of getting a shift like 10% of car users, to public transport, is exponentially worse than the cost benefit ratio of simply providing new roads and lanes; if there is even a benefit at all. Because most travel is done only at certain times of day, huge “investments” in rolling stock would be necessary to cope with such a shift. Roughly ten times as many people use cars as what use public transport. This means that a 10% decline in car use, shifting to public transport, requires nearly a 100% increase in public transport subsidies. It is a myth that increased patronage will bring efficiencies sufficient to negate this need, as long as public transport is not having to compete in a free market.

If we attempted to run a public transport based, car-free transport system, the cost would be greater than our entire current GDP and/or the lost flexibilities of individual motor vehicles would lead to massive economic contraction. Look at the former USSR. Do you think that their public transport was more efficient than our car use? Did you know that they were far worse wreckers of the environment on every measure, and used more resources per unit value of GDP, than capitalist countries?

Car-free societies absent totalitarian planning, were (Victorian England) and are (Slumdog Millionaire) mixed-use land use societies with people and animals living above and around factories and offices. We will only reach the stated aim of resource conservation and emissions reductions to the extent we return to such a society. Long distances are the main problem, not modes of transport.

Limiting sprawl does not achieve the desired result because of the effect on land prices. Alain Bertaud’s work on urban density profiles show that average commute lengths have increased in cities like Portland precisely because of this effect. The cost of land closer to the urban center becomes prohibitive, and most of the infill development takes place closer to the more affordable fringes. Seriously, take a look at his graphs.

Cities that have been allowed to develop closer to Lassez-Faire principles actually end up with lots of mixed use land use and multiple nodes and much lower average commute distances, and urban density profiles that slope evenly from the highest at the centre, to the lowest at the fringes. The low density at the fringes means that the commuting done by these people is of minimal effect, while the affordability of land is retained over the whole urban area, meaning that many people who could not have afforded to live closer to work under the controlled scenario, can do so under the “free” one.

Trains initially served the use of getting wealthy people over longer distances faster and in more comfort than horse drawn carriage. Trains have had their day long since. But we are doing ourselves serious economic and environmental harm with our mistaken assumptions about all public transport.

People run their own cars by choice. The taxes they pay for petrol alone, covers the cost of roads and externalities. It is public transport that does not pay its way even for running costs let alone externalities.

No-one would use public transport by choice if they had to pay the true cost.

The worst thing here is that people are being lied to about what their hard-earned rates and tax money being spent on public transport, actually achieves. It has never achieved cost-benefit justifiable reductions in road congestion and it has never achieved real reductions in resource use or emissions, let alone cost-benefit-justifiable reductions. We would have been better off in every way to have never spent a cent on public transport subsidies, and simply built more roads and lanes and had lower congestion.

If there were no public transport subsidies, and no government interference in transport, entrepreneurs would identify opportunities to run appropriate vehicles on appropriate routes at appropriate times of day, and make a profit on it.

If you understand economics, you will understand that if people buy product A because it is cheaper than product B, it is simply because the making of product A is a more efficient use of scarce resources than the making of product B. It is not necessary to attempt to trace the whole process from one end to the other: (refer to the essay “I, Pencil” by Leonard Read: to see how complicated it is to calculate all the inputs into making a pencil) the price is the quick answer.

If public transport fares absent subsidies would have to be more than people would pay, then it is not an efficient user of scarce resources. Actually, you do not have to look very far into the way Public Transport is run, to get a gut confirmation of this.

It is NOT a question of running 30 people from A to B by bus, compared with 30 people running their cars from A to B, and it never has been.

The 30 people get from 30 different “A”’s to 30 different “B’s”. To get the bus to pick them all up and drop them all off, would take so long that nobody would use it. The only people that use the bus today, are the small minority who it really suits.

The bus has to start somewhere empty and finish somewhere empty. Its average loading for the 1 trip is more like 15 people. Then it has to go back to the start mostly empty; average loading drops to below 10. That is just for the peak times of the day, which are the only times when running these services might make any sense at all. But then we have the lunacy of running that same bus around all day, with average loadings not exceeding 3 people. And I said “buses”, the same thing applies, only worse, to trains.

Why don’t ratepayers and taxpayers realise this? We are being fleeced for no good reason. The environment is not being saved and there are stuff all less cars on the road; if public transport use increases 10% there are only 1% less people on the road. It is exponentially cheaper to build new roads for the 10% odd people who do not yet use cars for their travel, than it would be to provide buses and trains for the 90% of people who do not use public transport: in fact the latter has been calculated to cost more than our entire GDP.

As for the social objectives of running buses and trains for poor people to use during the day, this is so expensive that we could provide hired stretch-limos for them at a lower cost, to pick them up at their door and drop them off where they want to go.

Public transport in its current subsidised, “social objectives” form, is actually doing more harm than good. It is a pretty good economic rule of thumb that if it needs subsidising at all, it is not an efficient use of resources.

Wendell Cox, in the above essay, points out that carbon credits for every tonne of CO2 reductions, is expected to trade for amounts of $10 to $30; but every tonne of reduced CO2 emissions gained through public transport substituting for private vehicle use, is costing in the region of several thousand dollars. You can argue Mr Cox’s figures till you are blue in the face, you simply cannot overcome that sort of order of magnitude in economic viability analyses.

Here are some conclusions from a European Parliament Conference on Transport Policy in July 2005.

“90% of travel in the EU is by car”. “Transport modes are not simply interchangeable”. “Public Transport operates effectively within specific niches”. “In the great majority of cases, travel by road cannot be made any other way”. “The smooth running of modern economies relies on road transport. Cars play a large role in economic productivity and the enlargement of markets”. “The high costs of public transport subsidies weighs heavily on Europe’s economy”. “The “external costs” (air pollution, etc) of vehicle use is covered many times over by the net taxation revenues specifically levied on road users”. “Since 1985, emissions levels of each new vehicle coming to market have been reduced by a factor of at least 10, and even though traffic volumes have increased, air quality in Europe’s cities is improving spectacularly”. “Investments in Rail would take 10,000 years to recoup in terms of reduced CO2 emissions”.

We can make huge gains in average vehicle efficiency yet; there are still people who buy V8’s by choice. Price rises will accompany resource depletion, and average vehicle efficiency will rise. Even with today’s technology, we could gain 70 or 80%. But of course there will be further technological advances. Heck, Greenies themselves talk about this out of one side of their mouths, when it comes to energy SOURCES, but they talk out the other side when it comes to energy CONSUMPTION by private vehicles using roads. I believe that new technology, electric cars and so on, will be very quickly supplied at affordable prices through manufacture in Chindia; at the moment they are made in small quantities in the USA or Europe and are just unaffordable. Think of the first one-piece carbon fibre bicycle frames and what they cost (Kestrel; $10,000?).

Internet-based car pooling/ride sharing alone, is an answer that public transport is not. ANY full car is already more efficient than even the fullest bus or train, and any car with two people in it is already more efficient than the current public transport average. I think if the authorities want to get serious about this issue, taxi licensing regulations should be abolished to allow anyone to carry a passenger for a fee. That would incentivise participation by all those drivers with spare seats.

Then we must return to more flexible uses of land. It makes no sense to force lengthy commutes through rigid zoning that was based on a previously popular ideology; society has taken one step forwards and two backwards. Along with dispersion of sources of jobs, we need interconnectedness to minimise trip distances and times by road. It is an economic impossibility to provide this interconnectedness by public transport.

The model being pursued by our planning classes now is just so wrong-headed that one suspects that they are driven by ideologies other than genuine concern for humanity and its environment. Their model will only work under conditions of such population density, that totalitarian rule would be necessary to achieve it. Alain Bertaud’s study on Atlanta concluded that Atlanta would need to abandon two thirds of its existing housing and retract back into the remaining one third, if public transport was to be viable. But of course the reconstruction that would be necessary, would consume so much resources that it would be doubtful whether recouping them would ever be possible through the alleged efficiencies of the higher density.

William Eager’s study in my above list, shows that increased population densities result in more road congestion, not less, for the simple reason that greater majority of the increased population moving into an area still opt for car use. The exceptions may be downtown Hong Kong and Manhattan.

Such high densities bring their own environmental and quality of life problems. It is far from certain that the resource efficiency and emissions of high density living are superior to urban sprawl. Urban sprawl is partly the result of choice and partly the result of zoning fashions of the past. Free market choice is actually a very good allocator of resources. I believe that those zoning fashions of the past have given us the longer commute distances that are our main problem today: under a freer market in land use, we might have had more urban sprawl but we would also have lower average travel distances.

We don’t have a “school zone” that we all pack our kids off to 30 miles away by train; I fail to see why we have to have “workplace zones”, if we really do have such a “crisis” of resources and emissions to confront.

Isn’t it funny how the political classes favored “solutions” to any problem invariably involve reductions in human freedom, even when an increase in human freedom would be a better solution, knowledge of which needs to be suppressed accordingly?

The reality is that even if peak oil is real and AGW is real, public transport is no fix. The same factors that will make free use of private vehicles less feasible will also apply to public transport. If we really do have to confront such a crisis, we will be forced to resort to freely mixed uses of land; it will simply be impossible to continue an urban planning model that implies lengthy commutes and focuses myopically on the mode of travel. It is absurd to imply that massive investments in electric rail or any kind of rail or even in buses, is responsible planning for an anticipated future crisis of resources or climate.

The inner city jobs to which people commute today, simply will not exist in the brave new, resource-scarce world and the greatly shrunken world economy. For a start, the government’s revenue simply will not be sufficient to pay the salaries of armies of bureaucrats; neither will most of the private sector office jobs be viable. The transport necessary for the support of modern living, particularly for the supply of food and necessities, will no longer exist; neither will the supplies of affordable electricity.

Apart from the fact that public transport is barely any more efficient than private cars, “travel and commuting” absorbs only around 11% of total energy consumed by households: 29% is from goods and services consumed, 28% from food, 20% from household uses (mainly electricity), 12% from construction and renovations. (Referring to the study “Consuming Australia”, by “the Centre for Integrated Sustainability Analysis” at Sydney University).

In this brave new world of depleted resources, what makes sense? Living in a wholly separate house with its own plot of surrounding land, where you can burn biomass to heat your home, cook on a barbecue, hang washing on a line, grow your own vegetables and fruit trees, collect rainwater, compost your own waste and recycle “grey water”, keep fowls or even a sheep or two, and have solar panels all over your roof and a wind turbine in the back yard? Or living in Green utopians high density inner city blocks of flats? This is a such a no-brainer, that these Green utopians very motives and veracity are very much in question. But for Mr Cox and many of his fellow contributors on this site, I have nothing but respect.

Excuse me, I just wish to emphasize the above couple of paragraphs, because they are of vital importance when added to Mr Cox’s argument.

Limiting sprawl does not achieve the desired result because of the effect on land prices. Alain Bertaud’s work on urban density profiles show that average commute lengths have increased in cities like Portland precisely because of this effect. The cost of land closer to the urban center becomes prohibitive, and most of the infill development takes place closer to the more affordable fringes. Seriously, take a look at his graphs.

Cities that have been allowed to develop closer to Lassez-Faire principles actually end up with lots of mixed use land use and multiple nodes and much lower average commute distances, and urban density profiles that slope evenly from the highest at the centre, to the lowest at the fringes. The low density at the fringes means that the commuting done by these people is of minimal effect, while the affordability of land is retained over the whole urban area, meaning that many people who could not have afforded to live closer to work under the controlled scenario, can do so under the “free” one.

http://alain-bertaud.com/images/AB_The%20Costs%20of%20Utopia_BJM4b.pdf

Take a look at the graph on page 12, of Portland’s urban density profile, in contrast to the normal urban density profiles of less-restricted cities, in which the density graph slopes evenly down from center to fringe. Bertaud rightly concludes that average commuting distances are driven UP as the result of urban limits and their effect on land costs and resulting patterns of development.

The only way around this, would be for literal confiscation of land value for owners of land closer to the urban centers, as that land becomes price out of reach for the very people the utopians expect to live there. I presume the reason that utopian planners and politicians have not yet insisted on this as part of their plan to save the planet, is that they are too plain stupid to grasp these mechanisms of basic economics at work.

Bertaud’s whole site, and all his papers, are a “must” for anyone who wishes to claim they understand these issues at all.

http://alain-bertaud.com/

I beg to partially disagree with the previous comment. I agree that Portland has failed to tilt the modal share towards mass transit, and if we only care about reducing GHG, after all cleaner cars in the future will probably allow us to achieve that without using more mass transit transportation. If I remember well Bertaud’s readings, the mistake that Portland made was not to increase the available FAR and size of its downtown to accommodate for additional mass transit commuting. Since it was not the case, prices would have risen in downtown and led some businesses to move elsewhere, leading to more polycentrism and a less effective transit system.

At the same time, it seems that we overlook something quite important here, which is traffic congestion. Whether cars are clean or not, the road infrastructure often cannot cope with peak hour traffic, resulting in hours of wasted time. I am French and I lived and worked in Paris and in the Paris suburbs, near Washington DC, in the Netherlands, in Japan and in Taiwan, and I can confirm that in many cases, riding in the subway or commuter train is MUCH faster than driving one’s car to go to work. When the transportation system is efficient, you take maybe 20 minutes for some travel which would take you 1 hour or more by car at peak hour. And this is not only in cities where local governments have implemented “anti-car” policies, but also in other cities where even large infrastructure can simply not cope with the amount of traffic there.

Private buses like you see in Manila for instance (jeepneys) are just part of the huge daily traffic jam and don’t offer any solution to relieve congestion.

Now, I agree that mass transit systems (complemented with bike and pedestrian networks) work only well in dense monocentric cities, or in dense, close knit polycentric urban fabric like in the Netherlands, and that driving your car is still more efficient in most of the US suburban areas unless they have been densified into TODs such as in the famous Arlington example. But I still think that, notwithstanding the specific situation in Portland, which I don’t know much about except for what this article says about it, mass transit often plays a very important role in relieving traffic congestion in the world’s metropolises.

Your articles don’t beat around the bushes exact t to the point.

window cleaning Barrie

The caliber of collection that you are providing is but marvelous.

Sell my Philadelphia Home

I have been searching for hours and I haven’t found such awesome work.

Kamagra

transport, actually achieves. It has never achieved cost-benefit hey there and thank you for your information – I’ve certainly picked up anything new from right here. I did however expertise several technical issues

I sent your articles links to all my contacts and they all love it including me.

zalando gutschein

But we’re uniquely qualified to make up for that. Premise makes your words work with copywriting advice delivered directly from your WordPress interface for each type of landing pageIrish Rugby Shirts

I’m not missing anything at all. Even for someone whose lactose intolerent and hates nearly all vegetables, I find enough to eat 😛 I expect I’ll become fully vegetarian in a few years. far from boring promotional products

congestion in road congestion I had been wondering if your hosting is OK? Not that I’m complaining, but sluggish loading instances times will very frequently

Great, This specific net webpage is seriously thrilling and enjoyment to learn. I’m an enormous fan from the subjects mentioned. Logo Design Brisbane

justifiable reductions in road using this web site, as I experienced to reload the web site a lot of times previous to I could get it to load properly.

Thank you very much for this useful article. I like it.

walk fit inserts

Thanks so much for sharing this awesome info! I am looking forward to see more postsby you!

web design los angeles

This blog website is pretty cool! How was it made !

SEO Edmonton

thank you for a great post.

https://www.rebelmouse.com/thepaleorecipebook/

Nice blog and absolutely outstanding. You can do something much better but i still say this perfect.Keep trying for the best.

https://www.rebelmouse.com/skintervention/

Friend, this web site might be fabolous, i just like it.

protoshares