Public transit systems intend to enhance local economies by linking people to their occupations. This presents problems for many low-income families dependent on transit for commuting. With rising prices at the gas pump, much hope has been placed on an influx of investment into public transit to help low-income households. But does public transit really help the poor? While the effect of transit access on job attainment is murky, several alternatives such as car loans and car-sharing programs have seen real results in closing the income gap. For Christina Hubbert, emancipation from public transit has been a change for the better. NBC News reports:

A car means Hubbert no longer spends two hours each way to and from work in suburban Atlanta. It means spending more time with her 3-year-old daughter — and no longer having to wake her up at 5 every morning so she can be in the office by 8. It also means saving hundreds of dollars each week in day care late fees she incurred when she couldn’t get to the center before its 6:30 p.m. closing time.

Research finds that car-ownership is positively correlated with job opportunities while no such relationship exists with access to transit stations. Furthermore, increased transit mobility has been proven to have no effect on employment outcomes for welfare recipients. The notion that newer and nearer public transit creates benefits for all is inaccurate; it only creates opportunities for those who live near the transit stations, and those opportunities are limited. A study by the Brookings Institute finds that, among the ten leading metropolitan areas in the US, less than 10% of jobs in a metropolitan area are within 45 minutes of travel by transit modes. Moreover, 36% of the entry-level jobs are completely inaccessible by public transit. This is not surprising given the fact that suburbia houses two-thirds of all new jobs.

The mismatch between people and jobs can be reconciled in two ways: car loans and car-sharing services. Basic car-sharing involves several people using the same car or a fleet of cars, as with the ZipCar. The concept has branched out to on-demand car sharing services, such as Lyft, mobile apps which link riders with drivers.

Car loans on the other hand have been around for a while and offer affordable financing for a car without a required down payment. Ways to Work, one of the largest loan providers in the U.S., includes courses on personal finance and credit counseling. By making vehicle travel more attractive, these two disruptive innovations threaten the expansion of public transit – and its powerful associated lobbies – in three ways:

1. It’s more cost-efficient and time-efficient.

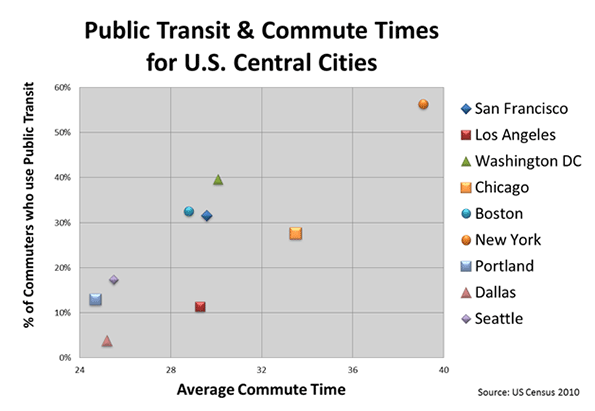

To improve the way we move people, transit developments must save both time and money. Sadly, transit lines are notorious for their extraordinary costs and long delays. Data from the 2010 Census reveals that people living in central cities with a higher proportion of transit riders experience longer commutes. And since transit riders have more cumbersome commutes, they are much more likely to be tardy or absent from work.

The hefty price tag of transit projects also triggers concern. For example, the cost per new passenger of the Washington Metro line to Dulles Airport was estimated at $15,000 annually. That’s about the same as the current poverty threshold for a household of two.

Car-loan programs on the other hand are largely cost-efficient, producing real fiscal benefits to borrowers, employers, and taxpayers. A survey of 4,771 borrowers and their employers finds that borrowers have greater job security as a result of access to vehicles. With access to credit, borrowers increase their purchasing power by an average of $2,900 each year and save about $250 by avoiding payday loans and checks-for-cash outlets. Employers gain as well through cost savings due to increase retention and reduced absenteeism and tardiness, which amount to $817 and $1130 per borrower respectively. In large part, providing vehicle financing is a smart investment since it reduces the number of low-income families on social welfare – an annual cost savings of $2,900 for each borrower coming off public assistance.

Given its clear advantages, car sharing is increasing. Recent reports find that shared-use vehicle organizations have been lucrative. Between August 2012 and July 2013, car-sharing ridership grew by 112 percent and the number of vehicles increased by 52 percent. And although car-sharing is not typically used to transport the poor, having on-demand car service makes it so that door-to-door access is more available and affordable. If car-sharing continues to grow at its current rate, it’s reasonable then to assume that these pseudo-taxi services will be eventually be affordable enough so that people would choose to be chauffeured rather than drive their own vehicles.

2. Vehicle ownership provides greater access to jobs and economic opportunities.

Instead of being limited to a few areas that are transit-oriented, families with cars have access to more jobs and economic opportunities. Public transit lines are limited in their geographical coverage and take time to make often numerous stops. Transfers are inefficient and time-consuming, making much of that coverage impractical. Also regular transit riders have limited employment options since they’re only able to consider jobs in the vicinity of transit stops and stations.

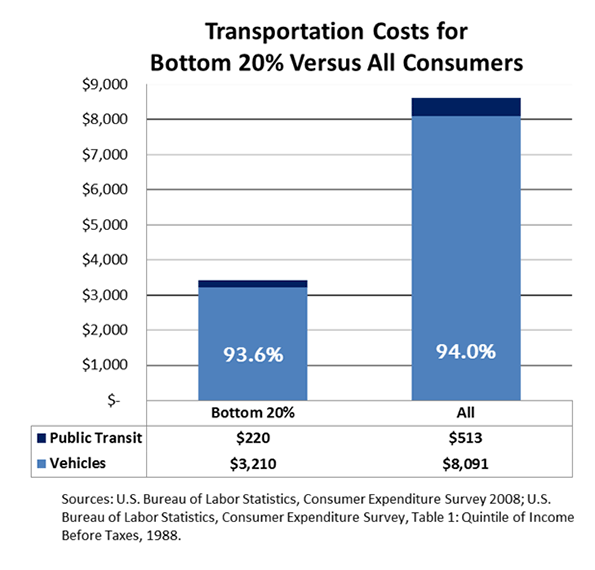

3. Travel by car is responsive to current travel patterns

A common misperception is that low-income people do not have cars. In reality, 86% of the poor have cars, compared to 95% of the entire population. The high percentage of poor families with cars reveals how automobile culture has become fixed into American ideals of economic well-being and prosperity. And contrary to stereotypes, the poor and the rich similarly spend about 94% of their transportation costs on vehicle travel versus public transit, challenging the notion that low-income travel behavior is unlike that of the rest of the population. As such, providing the poor with cars dramatically levels the playing field as they are the ones who would gain the most from increased access to employment destinations and education facilities.

A strong argument posited by public transit advocates is that as more cars use the road, congestion and pollution will intensify. And to be sure, public transit is more environmentally friendly than motor vehicles. The Amalgamated Transit Union (ATU), the largest union representing transit workers in North America, reports that one full bus eases the road of thirty-five cars, and that existing transit usage cuts national gasoline consumption by 1.4 billion gallons annually. Yet, on average, this result can only be achieved if buses were always full, which they are not – authorities from the Los Angeles Metro estimate that their buses run at an average of 42% capacity.

But is it equitable to ask the poor to forgo mobility and economic gain for the environment? Considering that most Americans experience some degree of social mobility via vehicle ownership, it’s far more reasonable to allow low-income families greater access to opportunity. In addition, new fuel efficiency standards for cars set by the Obama administration will decrease overall GHG emissions substantially; according to forecasts by the Department of Energy, carbon emissions from light-duty vehicles will drop 21% between 2010 and 2040 in spite of a 40% increase in driving. This shows that, even with more cars on the road, environmental goals can be accomplished.

Although the eligibility requirements are stricter in some areas than others, every state in the U.S. has a program for low-income residents to have access to car loans. Car-sharing is also rapidly expanding, but marketing now is geared towards millennials on a budget rather than low-income families. Both innovations, however, respond to new demands faced by future workers, who are likely to find employment in dispersed locations and may make more trips per workday since many may have multiple part-time jobs. With more efficient ways of getting people to work, it’s time to challenge the assumption that the expansion of public transit is the best way to meet the needs of America’s hard-pressed working class.

Jeff Khau graduated from Chapman University with a degree in business entrepreneurship. Currently, he resides in Los Angeles where he is pursuing his dual-masters in urban planning and public policy at the University of Southern California.

Photo by Romana Klee, #113 zipcar.

Comments

17 responses to “Mobility for the Poor: Car-Sharing, Car Loans, and the Limits of Public Transit”

The veracity of the claims in this article are highly suspect, and probably biased.

Car sharing programs have been shown so far to effectively work in transit-rich environments, not low density suburbs. I fail to see the relevance to the arguments made here.

Also, the suburbs of Atlanta are the worst possible example of an area lacking transit services; effective transit only covers about 40% of the Atlanta Area, e.g., the MARTA service area.

Given these factors, the points made by the article are extremely dubious, and sound more like libertarian anti-transit propaganda than valid academic research results.

So your point might be that Transit can be wound back and replaced with ride-sharing, at massive savings to the taxpayer, where transit is currently “viable”?

And what better could we do for people in the non-transit-friendly local environments, than give them, or subsidise, a car? The cost of trying to take transit to the 60% of Atlanta not currently served, would be many times more costly than giving the bottom 1% a car.

One of the most sickening things about rail transit subsidies is that they are not in the slightest, intelligent targeting of assistance to the poor. Most riders are not poor at all, and the more viable the transit system is (think Manhattan) the more disgraceful the capture of benefits by wealthy travelers and property owners.

What is the real number of individuals who would need a car vouchers based on their income being too low to afford a reliable car to navigate the suburban community that is built on the assumption that every trip is done by car?

If you are to argue that cars don’t need to be reliable, and that the working poor can get by with a decade old car that costs only $2000 a year to go unreliably a few thousand miles per year, then you create a world where the fast food worker showing up erratically is the norm because the car not starting or needing to sit in the street until money can be found to pay for a rebuilt engine is just the norm.

I notice job ads beginning to require applicants for low wage jobs have two reliable vehicles a few years ago, indicating the decline in standards for a reliable car. Clearly many employers were faced with firing workers who failed to show up for work because of car trouble. Attending community college as an adult from 2002-2006, I noticed two excuses for missing classes or dropping out – unreliable cars and unpredictable work schedules.

Public transit is the alternative provided for the working poor based on the working poor deserving to suffer from being second or even third class in society. No one is willing to make the right to a car a matter of public welfare policy.

The problem with car reliability that you are referring to, is one that has been steadily improving for decades and this is why automobility is part of the answer, not the problem.

Transit, on the other hand, has been steadily increasing in real cost per person mile, for decades. It is now in most cases, MORE expensive per person mile than running a car is – and it doesn’t take riders “anywhere” like a car does. It would be far cheaper to assist the poor with reliable automobility than try to bring transit to them.

Furthermore, location relative to transit routes is something that is rationed by real estate markets – hence most rail transit ridership is now by significantly above-average income earners. Way to go to “help the poor”, huh?

My practical compromise suggestion would be to abolish mass transit subsidies altogether and provide “mobility vouchers” to the poor, redeemable by anyone who provides them the service they need in a completely deregulated market. I suggest willing “ride sharers” would be numerous if there was remuneration involved, even of a fraction of the current level of cost of transit per person mile. In fact the whole system could be based on IT and electronic communications and GPS, and “the poor” could be given the handheld device that accesses the system for them.

This has the advantage that it would actually be the CHEAPEST way of doing it; there would not be a capture of the benefit of subsidies by well off riders and CBD property owners; and the poor would be provided with far greater “mobility” than the status quo.

The late great urban economist Colin Clark suggested something like this in his 1982 book, “Regional and Urban Location”.

From a colleague of mine:

The fundamental problem with the article’s “logic” is in this quote: “The mismatch between people and jobs can be reconciled in two ways: car loans and car-sharing services.”

WRONG. There is a third way in which it can be reconciled – by steering jobs back to transit-accessible locations. The author treats job sprawl as a fixed background condition and never considers the idea of treating the geographic distribution of jobs itself as the thing that needs changing. (We have addressed the job-sprawl problem in our report Getting To Work.)

New Jersey has recognized the opportunity to relocate jobs with a tax credit that rewards capital investment in transit-accessible locations (the Urban Transit Hub Tax Credit). The objective of the tax credit is to spark additional private investment and job creation in these locations. And it has been successful, attracting or retaining several large employers in areas easily reachable by transit, obviating the need for their employees to have access to a car.

Acknowledge the option of changing the geographic distribution of jobs, and most of the article’s other truisms suddenly no longer look to be so self-evident.

How many advocates of limiting employment locations to transit routes have thought of the following basic economic reality?

Anthony Downs; “A Growth Strategy for the Greater Vancouver Region”, 2007:

“……The cost of land poses a key dilemma for urban planners everywhere who want to concentrate jobs together so they can be best served by public transit. Such concentration raises the costs of land near centers; in fact, it would confer a monopoly advantage on landowners who owned such land and could exploit firms trying to locate there. Now firms want to locate elsewhere to cut their

land costs.

Planned concentration of jobs in a few centers is not consistent with private ownership and control of land. Some type of collective control over that land would be necessary to prevent monopolistic exploitation of land values. In theory, this could be done with high land taxes in such areas and special zoning rules. But adopting those devices is politically difficult in a free enterprise economy…….

“……A similar but less intensive dilemma concerns land near transit stops, where it would be most efficient to concentrate high-density housing and jobs. That also creates ownership monopolies over such land unless it is specially controlled or taxed. Yet focusing development near transit stops is a key to using more transit…..”

Subsidising employers to move to those locations merely adds to the monopoly capital gains captured by the property owners. A disgraceful wealth transfer from taxpayers.

WRONG. There is a third way in which it can be reconciled – by steering jobs back to transit-accessible locations.

Please explain the sordid history of the GEICO (yes, the Gecko, car insurance and the rest of it) property in Friendship Heights, Montgomery County, Maryland (Google Maps here).

This is about two blocks from the Friendship Heights station on the Washington Metrorail system’s Red Line in a county that has relentlessly supported transit as an alternative to building highways as far back as the early 1970’s.

Seems like a pretty good place for a lot of employment, right?

Umm, WRONG!

In the late 1980’s, GEICO wanted to significantly expand its operations on this site, but the solid citizen neighbors loudly objected, even though it was close to a rail transit stop. After several years of loud opposition and significant expense, the company threw in the towel in 1992 and instead built a massive new campus on U.S. 17 in Stafford County, Virignia (here).

Note the huge parking lot in front. Note that there is no Metrorail station (or any other transit) nearby (the closest Metrorail station is about 40 miles distant).

Perhaps you should reconsider your assertions?

From the Washington Post, dated 1992-02-13 by reporter Beth Kalman:

The decision by Geico Corp. to halt a planned expansion of its Chevy Chase headquarters and move 650 employees to Virginia, will cost Montgomery County up to $100,000 in income tax revenue and, initially, $300,000 in anticipated annual property taxes.

County Economic Development director Jon A. Gerson, tallying the hard numbers after Geico’s announcement that a failing economy and neighborhood opposition forced the move, said estimated losses are based on an assumption that up to one-third of the shifted employees are county residents who will either move away or join the ranks of the area’s unemployed. He said the situation represents “an opportunity lost.”

But the greatest impact, he said, will result from the loss of property tax revenue that would have been generated by Geico’s earlier plan to build a 500,600-square foot complex near its headquarters. Gerson said that if there had not been years of delay on the proposal, much-needed property taxes from the project would be about to start pouring into the county.

Although last week’s announcement that Geico plans to move came as no surprise, Gerson said, the pullout to rural Stafford County, which abuts Prince William County in Northern Virginia, is a “wake-up call” for Montgomery to streamline its development process. Other companies, which he declined to name, have issued signals, that they also are considering cheaper, less complicated places in which to do business.

I am very pleased to see a graph of the transportation costs for the bottom 20% versus the rest of society. I have always argued, and in fact Anthony Downs has made this point in his books, that the potential lowest cost of automobility is far below the “mean”, which is of course inflated by discretionary choices of expensive vehicles, by those who can afford them.

Besides this, there is the very significant cost of depreciation, which is avoided by poorer people buying already-depreciated cars. And as Downs points out, the improvements in reliability of cars as they age has been hugely beneficial to those buying the oldest ones.

This is why the poor overwhelmingly already have cars, and is yet another triumph of the free market versus central planning. So is the mobile phone ownership rate, and the microwave oven ownership rate, and so on.

The free market even beats planning hands down for housing affordability, too. You can get 10 times as much “home” for your money in a US city with a median multiple of 3, than you can in a UK city which has been centrally planned for 60 years now.

Do you have evidence the poor have the licenses they need to drive cars?

I see data that indicate the percentage of people with driver license has been declining since the early 80s.

Are those not allowed to drive a car stuck in their homes unless they are provided the vastly inferior public transit services that the market refuses to provide because the market serves only those with enough money to buy cars?

I grew up in the 50s and 60s when the only ones who road school buses were the farm kids, while the rest of us walked, biked, or used the city bus.

That changed, of course in the late 60s and 70s. It was at that point when suburban sprawl became the idea way of isolating the poor from the middle class. No longer could the city be divided by the tracks to the industrial zone with the poor living downwind of the pollution, and the middle class living on the other side of the tracks, with the city services convenient for the middle class to be served by the lower working class poor.

Instead of the tracks separating the middle class from the poor, it is now the car that separates them.

I can’t imagine any bipartisan support of a principle that everyone over the age of 17 has a right to a car in the same way the right to food, housing, and medical is recognized for all, and school is for those under age 17. If the poor get both car vouchers and housing vouchers and move in next door to the middle class in significant numbers, those suburbs will go the way of Detroit.

As long as you consider a society where everyone drives a car, those who can’t drive a car, the blind, infirm, disabled, the poor, the young, are relegated to second class status in the community, excluded from the life of the community on their own terms.

But this does seem to be a recurring theme – how to divide between us and them. If not the tracks to divide, then the car or lack of a car to divide.

I see your point. But there has been a massive shift of “the poor” of the past – those with the respectability and the ethics – into “bourgeoise” existences anyway. Prof. Nicole Garnett (Notre Dame) suggests there is “something unseemly in curtailing this process” by urban planning that makes all housing expensive, and gentrifies central areas, “just as the remnants of the previously excluded minorities are the main beneficiaries of this process”.

In fact, nothing has halted this process and left us with a crisis of unassimilatible underclasses who remain stuck in ghettoes, more than social and family breakdown. We can be thankful that so many “made it out of there”, in the past, but we have a serious problem with the remnants.

While racial prejudice may have been a problem in the past, what is far more significant is that people do not want criminals living next door and disruptive aggressive kids in their kids schools. Skin colour does not enter into it. “White trash” in UK cities have been “excluded” for decades.

Charles Murray has been right all along. Breakdown of social mores leads to underclasses that polite society can do nothing with other than incarcerate either in prison or in “ghettoes”. I suggest that “births out of wedlock” among the communities on the wrong side of the tracks, at a rate of 10% in the past, correlates with a high level of future social mobility among those people; and a rate of 70% correlates with future incarceration.

Socially mobile folk from the lower-decile communities among which births out of wedlock were 10%, were neighbours and community members and parents that suburbanites have had little problem with. But of course no-one wants socially immobile, aggressive and criminal “70 percenters” insinuated into their society.

I think arguing the merits of subsidised cars or transit for these people is irrelevant. Cars are clearly superior for those who are dedicated to “making it out of there”. Blind, disabled, young dedicated working poor can be helped far more cost effectively by community van services and other small-scale paid providers, not mass transit routes. But we need something other than physical-determinist urban and transport policy to resolve the problem of the remainder. Churches and faith played a massive role in the beneficial progress of the past. The secular State has nothing to fill the gap with.

Due to economy imbalance we have found various types of financial crisis in most of the countries. It is quite tough for people (those are belongs to poor category) to afford luxurious lifestyle. Basically due to low budget people were used to hire cars for rents instead of own them. Therefore we have found the concepts of car hiring, car loans, car sharing and pubic transits. So with the use of old and used cars we are able to own cars; therefore we need to visit our nearest car repair shops.

Car sharing is really a very nice service for the car lovers. This is providing by the Car Rental companies. Several car rental companies are there and particular they are now more focus on car sharing service for the people. Car sharing service is the self driving service in which the person taking the service will be the owner and operator of the car till the service lasts. It is quite good better than that of taxi services. Car service is definitely a good one for the car lovers and it will help to have the proper repairing of cars.

Especially people those are belongs to poor category are always suffer from various problems. Most probably due to low income system people were unable to ride cars and vehicles; so it’s better to adopt the system of car sharing and car loans; which is helpful in providing cab facilities to the people as well as allow them to own their personal vehicles.

Mercedes repair Gardena

This blog is financially more effective. Car rental and sharing both are two way of provide car service to normal public which have interest or need to have a car for a certain period of time and they don’t have enough money to buy a car. In such situation these financial services are very useful. Car rental and sharing are very effective and useful for both the car lover and the owner. Both got benefits through it. In other hand it help in our country’s financial growth and partially help to make our environment pollution free because due to these the number of buying car reduces. Benefits of car rental and sharing.

To develop the transportation system in the country; we have found that vehicle manufacturing companies were used to produce different types of vehicles with advanced features. But due to low family income or budget and rapidly increase of fuel price; people were suffering from various problems.

For a middle class family it is quite tough to afford a car; therefore they used to take the support of loans and finance. Therefore now government introduced various types of schemes such as; mobility for poor, finance, car sharing and car loans. I hope with the help of these above opportunities we are able to afford our own cars.

Volkswagen Repair Orange County