Urban form in American cities is in a constant state of evolution. Until recent years, American suburbia was often built without an appreciation for future evolution. This has left many older suburbs in a deteriorated state, and has accelerated claims of a more generalized suburban decline.

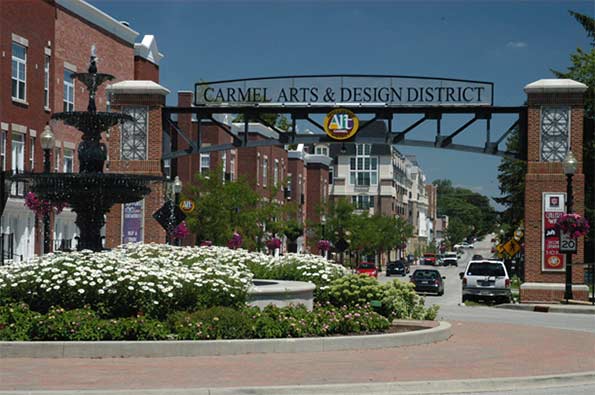

The Indianapolis suburb of Carmel represents a response to this historic pattern. While responding to today’s market demands with a new aspiration level designed to make it nationally competitive, it’s also trying to position itself for success tomorrow and over the longer term.

This is a critical issue for many suburbs. Like big cities before them, many older suburbs have now aged, and no longer necessarily meet the requirements of the marketplace.

There are many reasons for this. The early, usually small-scale Cape Cod-style housing common to many 50s vintage suburbs is not what today’s market is demanding. It’s the same for older enclosed malls – today “lifestyle centers” and other formats are preferred – many of which are now vacant, their grim remains featured on web sites such as DeadMalls.com. Many suburban areas were also built out with “infrastructure light” without upgraded streets, sidewalks, etc. leaving a big backlog of infrastructure need.

Across the country many of these older districts have fallen into decay and become increasingly poor, taking on many of the characteristics of the inner city. As the Brookings Institution noted over a decade ago, they “are experiencing some signs of distress—aging infrastructure, deteriorating schools and commercial corridors, and inadequate housing stock.”1 Today, the public is more aware of the trend, and events in Ferguson, MO recently gave a wakeup call to newer and still-thriving suburbs that they too may be troubled at some point.

Like other American cities, Indianapolis has many of these older, struggling suburban areas. In its case, many of them are within the core city limits due to a 1970 city-county merger. As regional growth continues to expand outside the central urban county, newer generation suburbs have a chance to learn from the struggles of many of their predecessors.

Carmel – pronounced like the Biblical Carmel – is the first suburb directly north of the city of Indianapolis. It is an upscale residential and business suburb similar to many others around the country such as Dublin, OH; Naperville, IL; and the Cool Springs, TN area. Its 2013 population of 83,573 made it the 5th largest municipality in the state. While not monolithically wealthy, its 2013 median household income of $100,358 is the 14th highest in the United States among communities of 65,000 people or more.2 It’s a preferred area for the estate homes of wealthy Indianapolis area residents, such as Indianapolis Colts owner Jim Irsay. But it’s not just a bedroom suburb; real estate brokerage Cassidy Turley reports that the Carmel submarket has over six million square feet of office space.3

Being located in the center of the favored quarter of the Indianapolis region, Carmel grew as an upscale area. This gives it a leg up in long term sustainability out of the gate.

Yet Carmel has not relied just on its wealth to insure against decline. Rather, it has embarked on a transformation program now nearly 20 years old from which three major themes emerge:

1. Responding to current market forces to build a “state of the art” community that is competitive globally, not just within the Indianapolis region.

2. Building a full spectrum of amenities and infrastructure to create a “complete city” with a high quality of life and intrinsic appeal that is a) not based solely on newness or low costs, and b) which has broad demographic appeal.

3. Attempting to create unique cultural and regional attractions to turn Carmel into a destination in its own right, as much city as suburb.

The primary driver of this transformation has been Mayor Jim Brainard, a Republican currently in his fifth term. Carmel long had top performing schools – it’s the top rated district in the state – houses with generous yards, low taxes, and other standard attractors of suburbia. Previous administrations had put in place key policies such as reserving the Meridian St. corridor for high end office space and banning billboards. But Brainard brought numerous changes in Carmel during his tenure including:

Annexation. Carmel has undertaken a series of annexations – nearly 20,000 acres since 2001 alone.4 With over 47 square miles of territory, Carmel has now largely achieved its desired geographic scale.

Parks. Carmel’s park acreage increased from 50 to 1000 acres and it has spent heavily on building out its parks. This includes building a $55 million Central Park, which includes a showplace community and fitness facility called the Monon Center.5 And the popular Monon Trail, a rail-trail through the length of the city that extended a previous project built by the City of Indianapolis.

Monon Trail at Main St.

Road Infrastructure. Carmel has invested heavily in upgrading the legacy network of county roads that it overgrew. This includes an aggressive deployment of modern roundabouts. Carmel now has over 80 of these, more than any community in the United States.6 It has upgraded miles of collector roads to urban standards with enclosed drainage, curbs, extra-wide travel lanes, landscaped medians, eight foot multi-use side paths on both sides of the street protected by a landscaped buffer zone, and decorative street signs and other detailing.

Roundabout at Main St. and Illinois St. in the fall

An upgraded segment of River Rd. in early winter

Two major state highways passed through the town, Meridian St. (US 31) and Keystone Ave. (SR 431). These were designed as rural style divided surface highways as is common in Indiana. Carmel convinced the state to relinquish Keystone Ave. to the city and give it $90 million for upgrades and future maintenance. Carmel converted this into a mostly free flowing parkway by spending $108 million to replace stoplight intersections with roundabout interchanges. These not only dramatically improved traffic flow, the bridges over the busy highway provided a high quality, safe connection – especially for pedestrians and bicyclists – connecting eastern and central Carmel, which had previously been separated by this “great wall” of a road. The state is currently performing a similar freeway upgrade on Meridian St., the principal office corridor.

Roundabout interchange at 126th St. and Keystone Parkway.

Water and Sewer Upgrades. Part of Carmel previously received water from the Indianapolis water utility. The City of Indianapolis had privatized this utility but sought to repurchase it. Carmel intervened in the process to pressure Indianapolis into selling it the water lines inside Carmel. Carmel has since undertaken significant infrastructure upgrades such as new wells and pumping stations. During a recent summer drought, Carmel, unlike Indianapolis, did not put in place a mandatory restriction on lawn watering.7

New Urbanism. Beyond core infrastructure, Carmel under Brainard has sought to change its style of development to embrace some of the more positive aspects of New Urbanism such as creating more urban nodes and walkability.

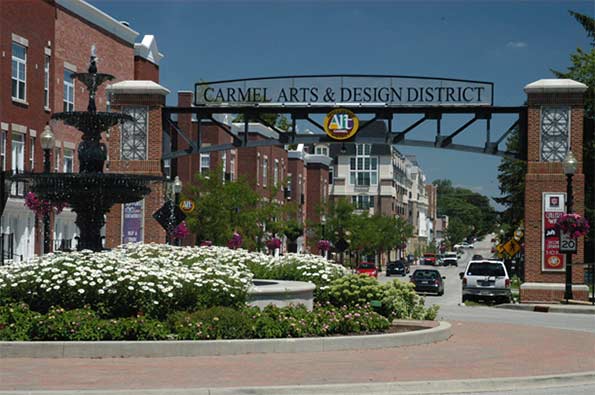

Unlike some traditional railroad suburbs or county seats, the historic center of Carmel was very tiny, and its Main Street populated mostly with one story buildings and empty lots. This was the first focus area, and started with fixing the physical infrastructure.

The city rebranded the area as the “Arts and Design District” and utilized Tax Increment Financing to promote multi-story, mixed use development. The result is a mostly occupied and often well-patronized Main Street district. The surrounding historic residential blocks have seen significant redevelopment activity as well.

Main St. at western fountain and gateway arch entryway to rebranded “Arts and Design Distrct.”

Beyond the historic downtown, Carmel has also implemented multiple New Urbanist style zoning overlays, including on Old Meridian St. and Range Line Rd. (the city’s original suburban commercial strip). These promote mixed use development, buildings that front the street, and multi-story structures. Infrastructure improvements and TIF have been used in these areas as well. There’s also a major New Urbanist type subdivision in western Carmel called the Village of West Clay.

Strip mall and traditional suburban development along Range Line Rd.

New Urbanist style development along Range Line Rd.

New Urbanist development and street improvements under construction on Old Meridian St.

The historic downtown was deemed too small to function effectively as the downtown of a city the size of Carmel today. The city thus decided to create a new downtown area called City Center. The location for this is an area south of the historic downtown area in an older suburban industrial zone that had fallen into a blight pattern. Much of it was vacant and what’s now the principal City Center development was built on the site of a failed strip mall. TIF was aggressively used here as well to redevelop the area.

The City Center development is only partially complete. A veterans memorial and other civic spaces are complete, as are several small office buildings, apartments, and a large mixed use complex. The anchor is a publicly funded $175 million concert hall called the Palladium and an associated theater complex with three stages.8 While these are complete, significant development remains to complete the City Center vision. The city also wants to redevelop the area between City Center and the old downtown, which they now label Midtown, but very little has been done to date.

Interior street of City Center development.

The goal of all this development is not the full urbanization of Carmel; this city does not aspire to be dense metropolis, or even Indianapolis. It’s rather about creating more town center type districts with the walkable feel that’s increasingly in favor, but without compromising the fundamental suburban character of the city. It’s also designed to create a city with options. Having a diversity of development styles within the city is part of a strategy of appealing to a more diverse demographic base, including singles and retirees, not just the stereotypical younger family with kids. Traffic flow has been improved, but short trips are now easier to undertake by foot or bicycle, not just by car.

Retro Architecture. Carmel has de facto mandated traditional architectural styles. There’s no one consistent style. Major buildings have been done in Georgian, Second Empire, and Neoclassical type designs. But modernism has been rejected, further differentiating suburban Carmel from urban areas that frequently elect for starchitecture that is unapologetically “of the now.”

The city has also attempted to prevent large corporations from building their standard architectural templates. Brick is effectively mandated, even for big box retailers like Lowes. Retailers like CVS and Kentucky Fried Chicken were forced to build second stories on their structures to locate in certain areas. Another Carmel CVS has an art deco façade.

The city wants high quality aesthetics and a unique sense of place. They also want “timeless” design, though like much New Urbanism architecture it can sometimes come across as pastiche.

Arts and Culture. As part of the attempt to appeal to more arts minded middle aged consumers, as well as members of the so-called “Creative Class,” Carmel has heavily invested in the arts. The City Center performing arts center was paid for almost entirely with public funds (TIF), an investment in the arts dwarfing even that of Indianapolis. The city has also paid for an extensive public art program, mostly statues by Seward Johnson. And it makes operating grants to local arts organizations such as the Carmel Symphony Orchestra.

Interior of the Palladium concert hall. Photo by Zach Dobson.

Seward Johnson is not a favorite of urban sophisticates. His statutes illustrate the type of play it safe art generally featured by Carmel. More sophisticated or cutting edge fare is not as prevalent. And there have even been some complaints by a limited number of citizens about items such as the classical nudes featured on the door handles of the Evan Lurie Gallery.

Brainard is thinking about the long term when Carmel is no longer the shiny new thing. As he put it, “Because we are designing a new city that will be in place for hundreds of years, the responsibility of doing it right falls to this generation…Carmel is a young city – we are still building our parks, trails, roads and sanitary sewer and water systems that will be here for centuries.”9

He’s also keenly aware of global economic competition and the fact that Indiana lacks the type of geographic and weather amenities of other places. He frequently uses slides to illustrate this point. In one talk he said, “Now this picture, guess what, that’s not Carmel; but this picture is the picture of some of our competition. Mountains – that’s San Diego of course, mountains, beautiful weather, you know I think they have sunshine what, 362 days out of the 365…. What we’ve tried to do is to design a city that can compete with the most beautiful places on earth. We’ve tried to do it through the built environment because we don’t have the natural amenities.”10 While the claims to want to equal the most beautiful places in the world may be grandiose, the key is that mayor believes Carmel’s undistinguished natural setting and climate requires a focus on creating aesthetics through the built environment.

What have the results been to date? Economically and demographically, the city has performed well. It has managed to create an environment that is proving competitive for business opportunities that might have previously bypassed Indiana. For example, American Specialty Health relocated its headquarters to Carmel from San Diego, with the CEO of the company personally making the move from La Jolla to Carmel.11 Geico also recently expanded. Numerous other corporations are either based in Carmel or have major white collar facilities there. The income levels are very strong, as noted above.

The city’s demographics have also expanded to become much more diverse. The minority population grew 295% between 2000 and 2010, adding 9,630 people and growing minority population share from 8.7% to 16.3%.12 12% of the city’s households speak a language other than English at home.13 Many of these are highly skilled Chinese and Indian immigrants working for companies like pharmaceutical giant Lilly. Even black professionals are increasingly moving to Carmel, with the black population growing 324% in the 2000s and black population share doubling to 3%.14 Carmel is not a polyglot city today, but it’s far more diverse than in the past.

Carmel has also attracted both national press and national awards. Money magazine ranked Carmel as the #1 best small city to live in 201215, and it’s scored highly in other surveys as well. Drew Klacik of the Indiana University Public Policy Institute notes that in an echo of the transformation of the city of Indianapolis since the 1970s, “Carmel has transformed itself from a desirable community within Indiana to a desirable and competitive community nationally.”16

However, it’s hard to argue that Carmel’s results materially outperform peer cities in other regions. Places like Dublin, OH and Cool Springs, TN have significantly more office space, for example. Many of those places are, however, implementing policies similar to those in Carmel . Most Carmel New Urbanist development continues to require TIF subsidies and is not yet sustainable at market rates. The city has obtained better financial terms in some recent deals, however. And despite major public investment and construction in the central city, many central area census tracts lost population during the 2000s.

The changes have also attracted significant criticism and opposition in some quarters. While the public remains largely positive on the results, there have been many critiques of the way they were done, some of them legitimate. A number of the projects had significant cost overruns. The mayor originally said that the Keystone project could be completed for the $90 million the state gave it. The actual cost was nearly $20 million higher.17 The Palladium was originally sold as an $80 million facility, but ended up costing $175 million. The city also said it planned to pay for ongoing operations by raising a $40 million endowment, but was unable to raise the funds, leaving it on the hook for $2 million in annual operating costs. These are not small misses.

Critics also pointed to state figures showing Carmel with nearly $900 million in total debt.18 While it is a wealthy community that can afford the payments, in a conservative state like Indiana, a suburb accumulating nearly a billion dollars in debt raises eyebrows. Carmel’s tax rates remain among the lowest the state, however.

The way the debt was accumulated has been criticized as well. The Palladium was paid for with TIF funds. Rather than bonds, the Carmel Redevelopment Commission – the authority that manages the TIF program and which was controlled by mayoral appointees – structured the Palladium debt as Certificates of Participation to circumvented the need for city council approval, incurring higher interest rates in the process. The city council later refinanced the debt at a lower rate using a general taxing power guarantee in what some called a bailout. In return for the refinancing, the council obtained more oversight over TIF activity.19

Though some controversy is inevitable and some criticisms are legitimate, ultimately the change program in Carmel has proven popular with the public and the city is booming, a boom that’s lending an increasingly bitter tone to the longstanding hostility Carmel has enjoyed from the region due to its status as the highest profile “rich suburb” in the region.

Yet for all the controversy, many regional suburbs are copying some aspects of Carmel’s approach, with roundabouts now a regular feature in area communities and major park programs and New Urbanist style town center developments as well. This includes the massive sports-oriented Grand Park in Westfield and the Nickel Plate District in next door Fishers’ town center.20

It’s also clear that peer type suburbs around the country are adopting similar strategies, such as Dubin, OH’s Bridge Street Corridor proposal21 or Sugar Land, TX’s $84 million performing arts center.22 Imitation, they say, is the sincerest form of flattery. Carmel represents the leading edge of the emergence of a new type of post-Edge City aspirational suburb. It’s something we may be seeing a lot more of in the future.

Aaron M. Renn is a senior fellow at the Manhattan Institute and a Contributing Editor at City Journal. He writes at The Urbanophile.

————————————-

1 Robert Puentes and Myron Orfield. “Valuing America’s First Suburbs: A Policy Agenda For Older Suburbs in the Midwest,” Brookings Institution, 2002.

2 U.S. Census Bureau, “American Community Survey 2013 1-yr”, Table B19013.

3 Cassidy Turley, Indianapolis Office Market Snapshot (Third Quarter 2014), 3.

4 Ellen Cutter. “Explaining the annexation process,” Greater Fort Wayne Business Weekly, June 12, 2014. Accessed January 8, 2015. http://www.fwbusiness.com/opinions/columnist/businessweekly/article_f42da036-6182-575a-8445-274cd82ca296.html

5 Matthew VanTryon. “Carmel then and now: World’s Apart,” IndianapolisNewsBeat.com, December 16, 2014. Accessed January 8, 2015. http://blogs.butler.edu/multimedia-journalism/2014/12/16/carmel-worlds/

6 James Brainard, transcript of speech at 2014 International Making Cities Livable Conference, June 23-27, 2013.

7 “Why no watering ban in Carmel,” WISH-TV News, July 12, 2012. Accessed January 8, 2015. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=y51BJYM4Fgc

8 David Hoppe. “The Palladium’s boffo budget,” Nuvo Newsweekly, June 20, 2011. Accessed on January 8, 2015. http://www.nuvo.net/indianapolis/the-palladiums-boffo-budget/Content?oid=2275080

9 James Brainard, notes for 2014 State of the City Address.

10 James Brainard, transcript of speech at 2014 International Making Cities Livable Conference, June 23-27, 2013.

11 Andrea Muirragui Davis. “Wellness provider beefing up new Carmel office,” Indianapolis Business Journal, October 29, 2014. Accessed on January 8, 2015. http://www.ibj.com/blogs/11-north-of-96th/post/50241-wellness-provider-beefing-up-new-carmel-office?id=11-north-of-96th

12 U.S. Census Bureau, calculations by author from Census 2000 and Census 2010.

13 U.S. Census Bureau, “American Community Survey 2013 1-yr”, Table B05007.

14 U.S. Census Bureau, calculations by author from Census 2000 and Census 2010.

15 “CNNMoney Ranks Americas Best Places to Live,” Daily Finance, August 20, 2012. Accessed January 8, 2015. http://www.dailyfinance.com/2012/08/20/cnn-money-ranks-americas-20-best-places-to-live/

16 Drew Klacik, telephone interview with author, December 29, 2014.

17 “Brainard seeks bonds to finish Keystone,” The Indianapolis Star, October 18, 2009. Accessed January 8, 2015. http://archive.indystar.com/article/20091018/LOCAL/910180409/Brainard-seeks-bond-finish-Keystone

18 Indiana Department of Local Government Finance. “Local Government Debt Report,” September 21, 2012, 15.

19 Kathleen McLaughlin. “Brainard seeks deal on maxed-out TIF,” Indianapolis Business Journal, March 31, 2012. Accessed January 8, 2015. http://www.ibj.com/articles/33569-brainard-seeks-deal-on-maxed-out-tif

20 Cara Anthony. “New look for the Nickel Plate District in Fishers,” The Indianapolis Star, June 28, 2014. Accessed January 16, 2015. http://www.indystar.com/story/news/local/hamilton-county/fishers/2014/06/27/new-look-nickel-plate-district-fishers/11537251/

21 Brent Warren. “Dublin Moves Ahead With Bridge Street Corridor Plans, Connecting Across River,” Columbus Underground, March 23, 2013. Accessed January 8, 2015. http://www.columbusunderground.com/dublin-moves-ahead-with-bridge-street-corridor-plans-looks-to-connect-across-river-bw1

22 Rebecca Elliott. “Sugar Land breaks ground on $84 million performing arts center,” Houston Chronicle, December 9, 2014. Accessed January 12, 2015. http://www.houstonchronicle.com/neighborhood/fortbend/news/article/Sugar-Land-breaks-ground-on-84M-performing-arts-5946247.php