A couple weeks ago the Economist ran a leader and an article on the plight of smaller post-industrial cities, noting that these days the worst urban decay is found not in big cities but in small ones. They observe:

Partly, this reflects the extraordinary success of London and continuing deindustrialisation in the north of England. Areas such as Teesside have been struggling, on and off, since the first world war. But whereas over the past two decades England’s big cities have developed strong service-sector economies, its smaller industrial towns have continued their relative decline. Hartlepool is typical of Britain’s rust belt in that it has grown far more slowly than the region it is in. So too is Wolverhampton, a small city west of Birmingham, and Hull, a city in east Yorkshire.

…

And even with growth, the most ambitious and best-educated people will still tend to leave places like Hull. Their size, location and demographics means that they will never offer the sorts of restaurants or shops that the middle classes like.

Their editorial forthrightly embraces a policy of triage, saying “The fate of these once-confident places is sad. That so many well-intentioned people are trying so hard to save them suggests how much affection they still claim. The coalition is trying to help in its own way, by setting up ‘enterprise zones’ where taxes are low and broadband fast. But these kindly efforts are misguided. Governments should not try to rescue failing towns. Instead, they should support the people who live in them.”

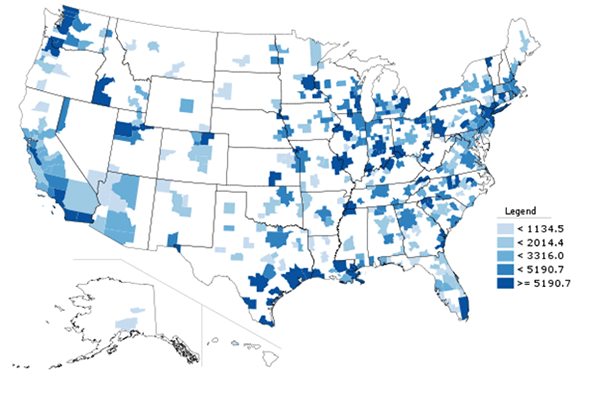

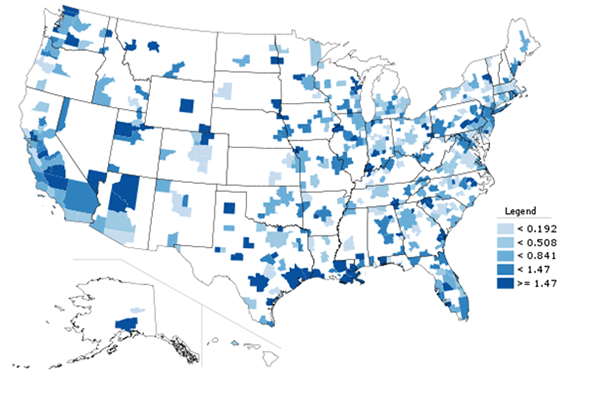

This same dynamic is clearly evident in the United States as well. Bigger cities have tended to weather industrial decline far better than smaller ones. There seems to be some threshold size below which it is difficult to support the infrastructure, the amenities, and the thick labor markets that attract the people and businesses in 21st century growth industries. My “Urbanophile Conjecture” heuristic suggests that you need to be a state capital with a population greater than 500,000 to be thriving. But even larger places that aren’t capitals and conventionally viewed as failures like Detroit retain powerful metro area economies and large concentrations of educated workers, especially in the suburbs. Conversely, smaller places like Youngstown, Ohio and Flint, Michigan face much bleaker circumstances.

There are exceptions to the rule, including many delightful college towns or the occasional oddball like Columbus, Indiana, but for the most part smaller post-industrial cities have really struggled to reinvent themselves.

In part this is because a rising tide hasn’t lifted all boats, only some of them. As economist Michael Hicks noted, “Almost all our local economic policies target business investment, and masquerade as job creation efforts. We abate taxes, apply TIF’s and woo businesses all over the state, but then the employees who receive middle class wages (say $18 an hour or more) choose the nicest place to live within a 40-mile radius. So, we bring a nice factory to Muncie, and the employees all commute from Noblesville.”

In short, growth actually fuels divergence because a) the growth disproportionately accrues to the places that are doing well in the first place and b) even when struggling cities can attract jobs, people earning middle class wages frequently live elsewhere. Doug Masson likened this to Jesus’ statement that “For he that hath, to him shall be given: and he that hath not, from him shall be taken even that which he hath.” I think there’s a lot of evidence that for bigger cities a lot of activity is exhibiting a convergent or flattening effect. That’s why so many places today have decent startup scenes, quality food, agglomerations of talent, etc. But for smaller cities my observation is that it’s still a divergent world.

You see this on full display in central Illinois, where the town of Danville (population 33,000) and Champaign-Urbana (combined population 124,000) are only about half an hour’s drive apart on I-74. Danville is one of the bleakest towns I’ve ever visited in the Rust Belt. When your Main Street is a STROAD, you know you’re in trouble. Champaign-Urbana by contrast, is a fairly healthy community. It’s home to the main campus of the University of Illinois, seems to be reasonably thriving, has many high quality residential streets, a direct rail connection to Chicago, etc. As a college town, it’s one of those “exception” smaller places.

Anyone within reasonable driving distance with a choice would almost undoubtedly choose to live in Champaign over Danville, unless they had a family or personal connection to the latter. It’s an easy slam dunk decision. In effect, proximity to Champaign acts as kryptonite to Danville’s revitalization. Again, a rising tide only fuels this divergence.

This sort of divide between communities mirrors the divide in society as well. The question is, what approach should be taken to address these disparities? One approach is to focus on the people, and leave the places to rot. Jim Russell has noted that “people develop, not places” thus most place based economic strategies are destined to fail. This approach has also been advocated by economist Ed Glaeser, who in an article title, “Can Buffalo Ever Come Back?” answered his own question by saying, “probably not—and government should stop bribing people to stay there.”

This is obviously unpalatable to policy makers of either the left or the right, as no one has yet embraced it openly. How then have the left and right responded? The response of the left seems to be what Walter Russell Mead has labeled the “blue model” solution. His basic view is that the post-war economy was based around a policy consensus he labeled the blue social model (and which Urbanophile contributor Robert Munson has simply labeled the New Deal). This involved large corporations, powerful unions, extensive industrial regulation, and an expanding safety net. Those who wish to retain the model suggest allowing divergence to continue, but raising taxes on the wealthy and successful in order to redistribute them to sustain those at the bottom of the ladder (via an expanded welfare state), who are in effect seen as lost causes in the modern global knowledge economy, though few of them will openly say it. So the idea is to invest in success, and redistribute the harvest aggressively. That’s why you see lots of left advocacy in favor of tax increases on higher income earners and against food stamp and other benefit cuts, but a paucity of ideas for how to provide the left behinds with jobs and opportunity.

Mead suggests there’s no such thing as the red social model, and perhaps he’s right in that there’s never been a national policy consensus we could label as such, but there’s certainly a red model response to current conditions and it’s called the Tea Party, or what Mead has labeled a “Red Dawn” in many places like Kansas, North Carolina, and New Mexico. This is a type of single factor determinism model. In these kinds of models, a single factor like education, transportation infrastructure, climate, etc is treated as overwhelmingly determinant in driving the economic structure and outcomes. The factor posited by the Red Dawn model is government, therefore the red model response is to slash and burn government (with the potential exception of highway spending) to lower costs, taxes, and regulatory barriers that are perceived to be holding the economy back. In other words, government is the base, and the economy and everything else is the superstructure. Fix the base and the superstructure will correct itself. That’s the theory.

Broadly speaking, these are the paths that Illinois and Indiana have followed. Chicago’s size enables it and its values to political dominate the state in the modern era. With only a rump of a Republican Party, the Democrats are free to do what they like. Conversely, in Southern influenced Indiana it is the outstate areas that are numerically superior to the successful urban regions, thus the state follows their policy preference, and Republicans overwhelmingly dominate the state so there’s little real opposition to red model policies.

What have the results been? Most obviously, Illinois is nearly bankrupt while Indiana is sitting on a AAA credit rating and a $2 billion surplus in the bank. (It has a pension deficit, but it’s manageable and there’s a funding strategy in place). Clearly Indiana has a more functional political system than Illinois, which somehow manages to remain gridlocked despite a “four horseman” style legislative system and overwhelming Democratic dominance. So score two for Indiana.

Finances aside, what have the results been? Illinois has poured massive quantities of cash into building on success, with items like the O’Hare Modernization Program and Millennium Park. The successful side of the economy, epitomized by the global city portion of Chicago, has soared to incredible heights. This is a city that earned at seat at the table of the global elite. On the other hand, the overlooked areas like much of the south and west sides of Chicago and places like Danville, are in horrific shape. The goal of allowing divergence clearly worked. However, with the state’s finances in abysmal shape, the redistribution portion did not happen. Indeed, the social safety net and basic services depended on by the rest of Illinois are being shredded. Even if you believe that it’s viable to simply support a large lumpenproletariat in perpetuity on welfare – which is doubtful – financial extremis means Illinois isn’t even able to try.

Meanwhile in Indiana, pretty much the entire state policy has been reoriented towards making the left behind areas attractive to lower wage businesses. Policies that would cater to higher end businesses in successful urban areas have been less popular. That’s not to say there’s been nothing. Gov. Pence recently agreed to subsidize a non-stop flight between Indianapolis and San Francisco to help the local tech industry, for example. And he’s supported efforts to boost the life sciences sector. But I think think it’s fair to say low costs and low taxes are the watchword, with right to work, light touch environmental regulation, mass transit skepticism, etc.

However, most of Indiana’s left behind type places have not recovered. Overall the state has retained a stubbornly high unemployment rate significantly above the US average, and, even more worrying, incomes have been declining relative to the US. Metropolitan Indianapolis, Lafayette, Bloomington, and Columbus have done reasonably well. Much of the rest of the state has continued to struggle, particularly in adding jobs with middle class wages. As the recent commentary by Brian Howey, Michael Hicks, and Doug Masson shows, Indiana retains its “Noblesville-Muncie” divides mirroring Illinois’ “Champaign-Danville” ones.

In short, the blue and the red model produced some success, albeit in different modes (think San Francisco vs. Houston, Chicago vs. Indianapolis), for the “haves” side of the equation but haven’t yet proven equal to the “have nots.” The Economist makes it clear the totaly different policy configurations of the UK haven’t made a dent in it either. Post-industrial blight in much of Europe tells a similar tale. This suggests that there are powerful macro forces at work that are extremely difficult if not impossible to overcome. It’s no surprise then that the Economist suggests giving up.

Again, that’s not likely, so what should we do? I won’t pretend to have all the answers to a very difficult question. However, I’ll suggest a few possibilities:

- Seek to stop the civic death spiral. This means getting ahead of the decline curve by seeking to halt the cycle of people and businesses leaving, leading to revenue declines and degraded quality of place, leading in turn to to service cuts and tax increases and disinvestment, which leads to more people and businesses leaving. This involves getting ahead of decline and restructuring government to a place where you can hold a defensible position on services and taxes from which you can seek to rebuild.

- Integrate with metropolitan economies. Rather than Muncie trying to hold Noblesville/Metro Indy at bay, or Danville the same to Champaign, closer connectivity is the key. I’ve written on this before regarding Indiana. In the short term losing the highly paid employees to a nearby municipality is a good thing. Without those living options for the managers, etc. you’d never be in play for the plant in the first place. That connection expands your labor pool, provides trade opportunities, etc. Just the property taxes from the plant is valuable, and can be used in rebuilding. Fostering these connections would require decisions that seem counter-intuitive on the short run. For example, Ball State University in Muncie should clearly expand its downtown Indianapolis presence. That isn’t necessarily taking away from Muncie. It’s building new connections and opportunities for Muncie where they don’t exist today.

- Find a claim to fame around which to rebuild. Carl Wohlt says that every commercial district needs to be known for at least one sure thing. Similarly, what’s Danville’s sure thing? Some towns like Warsaw or Elkhart already have it and need to build on it. Others need to find one. That’s not to say one thing is the only thing you’ll ever need or that you aren’t opportunistic around potentials deals that come your way. But you have to start somewhere. Where do you put your limited available civic funds?

I’m not so naive as to think this it the complete answer. But if there’s to be a genuine attempt to rescue places, then new thinking is needed and a turnaround will take a long time. In the meantime in parallel, clearly people-centric solutions also need to be pursued, to give people the best opportunity to realize their potential and dreams in life, where ever that may take them. No city is a failure that does this for its citizens.

Aaron M. Renn is an independent writer on urban affairs and the founder of Telestrian, a data analysis and mapping tool. He writes at The Urbanophile, where this piece originally appeared.

Photo by Randy von Liski