I’ve observed many times that cities outside of the very top tier almost always come across as generic, cheesy, and trying too hard in their marketing efforts. They highlight everything about their city that is pretty much a variant on things everybody else already has (beer, beards, bicycles, etc) while downplaying the things that truly reflect their community. Call it “aspirational genericism.”

Most places are extremely desperate to be part of the cool kids club, and so they buy the right preppy clothes, etc. and treat the things that are authentic and true about themselves as something to be ashamed of instead of celebrated.

Today lots of cities produce videos to showcase themselves. But a while back it was cities commissioning songs, hoping for something like Frank Sinatra’s standards about New York and Chicago. These were for the most part embarrassingly cringe worthy.

Indianapolis did the same a while back, in an effort I won’t given specifics on to protect the guilty, who were, after all, operating with the utmost sincerity.

What I do want to highlight is though is that Indianapolis has one of the greatest songs ever recorded about a city, the Bottle Rockets’ “Indianapolis.” I have not, however, ever heard anyone in the city actually bring it up.

And it’s easy to understand why. The song is an extremely negative take on the city in every respect. The refrain is:

Can’t go west

can’t go east

I’m stuck in Indianapolis

with a fuel pump that’s deceasedTen days on the road

Now I’m four hours from my hometown

Is this Hell or Indianapolis

with no way to get around?

He proceeds to regale us with a series of humorous but negative observations about the city, such as:

Who knows what this repair will cost

Scared to spend a dime

I’ll puke if that jukebox

Plays John Cougar one more time.

Having seen the Bottle Rockets in concert many times, I can tell you that songwriter and lead singer Brian Henneman really does seem to dislike Indianapolis, where he apparently had an actual bad experience. (His hometown is somewhere near St. Louis, and he spent a lot of time with the Uncle Tupelo crew in Southern Illinois – and environment one would not expect to encounter someone looking down on Indy).

Nevertheless, this is an amazingly great song. Here’s a 1991 acoustic demo version recorded with Jeff Tweedy and Jay Farrar. If the video doesn’t display, click over to listen on You Tube.

While it’s probably a bridge too far to suggest that the city should embrace this song as a branding anthem, I’d like to point out that many nicknames and branding aspects of cities started out as digs. And let’s be honest, the idea of being trapped in Indy without a car isn’t that far from the truth. I might also observe that gangster rap became a phenom precisely because it did not deny the reality of life in the inner city.

Here’s another, though not a song but a TV commercial. This one is a local legend. You’ll have to watch it to believe it. It’s a TV ad for local institution “Don’s Guns.” The eponymous Don was famous for his slogan, “I don’t want to make any money, folks. I just love to sell guns.” If the video doesn’t display for you, click over to watch on You Tube.

If you search “Don’s Guns” on You Tube you can watch a variety of other colorful ads.

Again, this is not likely to be something that will be used in the chamber of commerce’s marketing materials anytime soon. But if you don’t live in Indy, wouldn’t you find the idea of a bunch of people there who love guns believable? Of course you would, because it’s true. Indiana is a state that explicitly includes a right to bear arms for self defense in its constitution. Now, many people locally may not like guns, but at some point people are going to discover the actual reality of the place, even if you don’t tell them about it. And believe it or not there’s a large market of people who have an interest in guns. If you want to try to market to the gun-free crowd, are they likely to put Indy at the top of their list anyway? You’re probably fighting an uphill battle.

Then lastly back to music. If there’s one thing that people around the world know about Indianapolis, its the Indianapolis 500. So it’s no surprise that the city and race were featured in the 1983 song “Indianapolis” by Puerto Rican boy band Menudo. There’s even a music video for it. You should click over to watch on You Tube as this copyrighted music has playback restrictions.

This one, it’s true, is a cultural relic that has not stood the test of time, other than for retro flourish purposes (though it’s not a bad song). But it seems to be little known locally. I didn’t know about it until a message board commenter linked some years back. And I haven’t seen a marketing campaign around the city focused on auto racing in a long time.

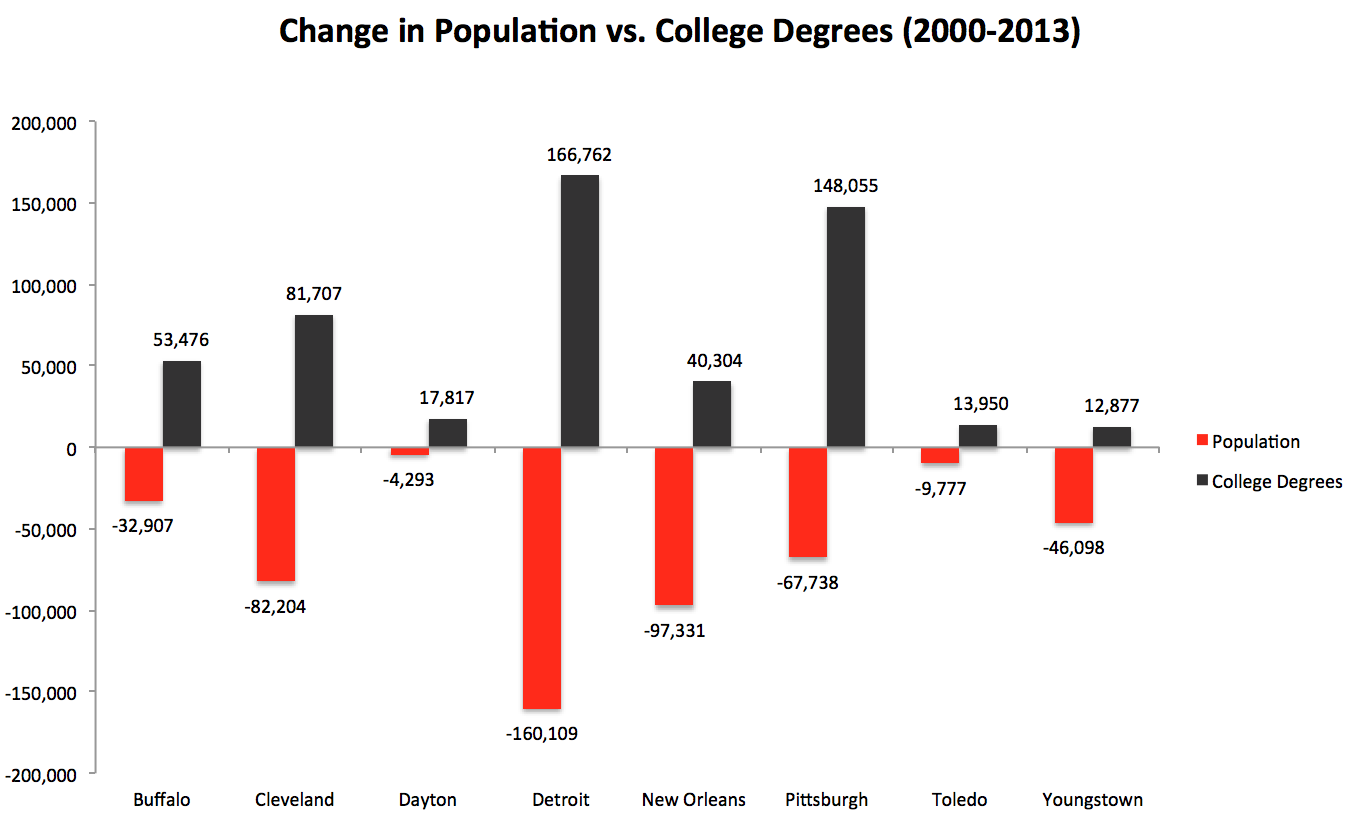

The struggles of working class life in a car dependent town, guns, and auto racing. Not the makings of glamour, but certainly authentic. Jim Russell and others have written a lot about rembracing the industrial heritage of the Midwest as “Rust Belt chic.” Indy is not really Rust Belt in the same sense as Cleveland or Pittsburgh. But these items are part of its own unique take on the formula. What could potentially be done with them?

Certainly Texas has done well by being Texas. And Nashville has succeeded by being unapologetic about country music. And I’ll point out again that the Midwest repudiated its own heritage of agriculture, workwear, and blue collar lagers only to have them picked up by Brooklyn hipsters and made cool again. The Midwest threw its culture away and Brooklyn bought it out of the thrift store. Now the region is reimporting is own birthright after it has been made “safe” by the embrace of the cool kids. Midwest cities should have owned local and urban agriculture. But of course, in a region of places like Columbus that are deeply ashamed of being seen as “cow towns”, that was simply impossible. If Brooklynites ever start buying up old Chevy Vans, expect that only then will a place like Indy embrace the reality of that culture as well.

Aaron M. Renn is a senior fellow at the Manhattan Institute and a Contributing Editor at City Journal. He writes at The Urbanophile, where this piece first appeared.