On July 18, at a site pregnant with symbolism — the future location of what HSR advocates hope will become San Francisco’s terminus of the state’s bullet train — California Gov. Jerry Brown signed a bill to fund construction of the first section of the high-speed line. Earlier in the day, Brown had traveled for a similar ceremony to Los Angeles, the other "bookend" of the project. The bill signing ceremonies followed the state Senate’s approval (by a single vote) earlier in the month of nearly $8 billion in state and federal money to build the initial section of the line in the Central Valley and to make a series of transportation infrastructure improvements in the LA and Bay Area.

According to sources at the California High Speed Rail Authority (CHSRA), the total infrastructure commitment now involves:

* $6 billion for construction of the first section of the high-speed line in the Central Valley ($2.7B of state HSR bonds and $3.3B of federal ARRA funds);

* $1.2 billion for electrification of Caltrain, the commuter rail line in the SF Peninsula (half from state HSR bonds and half from local funds);

* $1 billion for San Francisco’s Central Subway (of which $61M is in HSR "connectivity" funds and $930M in federal New Starts money);

* $1.5 billion in other connectivity improvements (BART car replacements, LA Metrolink upgrades, LA regional connector, grade separation improvements) funded by the remaining "connectivity" funds, which must be matched ; and

* $1 billion in other SoCal projects ($500M from state HSR funds which must be matched).

As can be seen from the above summary, almost half the funding is for upgrades to conventional transit/commuter rail services in LA and the Bay Area. Much to the chagrin of high-speed purists, the project has morphed into a statewide transportation program much of which is totally unrelated to the high-speed rail initiative approved by the voters in Proposition 1A.

Whether this shift in emphasis represents "a giant fraud perpetrated on the voters who passed Proposition 1A and voted for a true HSR system;" or whether this is a "victory for common sense, a decision that wisely places greater value on satisfying present-day needs than on promises and conjectures of distant-in-time benefits" depends on one’s point of view (both are direct quotes from our interviews.) While bullet train visionaries will view the "bookends" strategy as a betrayal of the original Prop 1A pledge, pragmatists will hail it as a prudent and realistic move to gain political support and a hedge against the uncertainties facing the high speed rail project. Just what obstacles confront the project in the months ahead can be gleaned from the discussion below.

Obstacles and Uncertainties

Despite the celebratory and self-congratulatory tone of the Governor’s speech, the project faces a number of impediments that could delay it for years if not put an end to it altogether. As a headline in a Wall Street Journal article put it, "For Now, the Bullet Train May Go Nowhere." (WSJ, July 8, 2012). The hurdles the project must overcome include:

* A major lawsuit asserting that the Central Valley line project as proposed and approved by the Legislature does not comply with various provisions of the enabling Proposition 1A. According to the plaintiffs, the deficiencies include:(1) no electrification, (2) lack of a "useable segment" (the 130 mile section in the Central Valley by itself is claimed not to satisfy the requirements of an operable segment); (3) lack of adequate committed funding; (4) trip times above the promised 2 hrs 40 min; (5) the need for an operating subsidy; (6) inability to meet the Federal requirement to complete project by September 2017; and (7) inability to meet the promise of a "one-seat ride" from LA to SF (the "blended" approach would require at least one transfer). (John Tos, Aaron Fukuda and County of Kings v. California High Speed Rail Authority). The suit is moving toward trial sometime in 2013.

* A lawsuit filed by the Madera County and the Madera and Merced County Farm Bureaus asking for a preliminary injunction to block rail construction in the Central Valley, slated to begin later this year. The suit asserts that the rail line would disrupt 1500 acres of fertile land by cutting off irrigation canals. Officials of the two bureaus say more than 500 farmers whose land lies in the path of the rail line plan to fight any attempts by the state to seize their properties by eminent domain. "It’s going to be a long battle for the Rail Authority," said executive director of the Merced County Farm Bureau. "There is going to be opposition every step of the way."

* Several lawsuits challenging the Program level EIR for the Bay-Area-to-Central-Valley section of the statewide project. A victory by the challengers of the Program EIR would "undo" the project level EIRs for the Central Valley construction project, according to Gary A Patton, an attorney who has been involved in the litigation.

* Several environmental lawsuits charging the HSR project with violations of the state environmental law (CEQUA) and the Endangered Species Act. The Governor, under pressure from environmentalists, has recently withdrawn his threat to waive CEQUA requirements.

* The possibility of a legal challenge that Proposition 1A money is being used "unlawfully," i.e. for non-HSR projects, in the "bookend" areas.

Any of the above actions could delay the issuance of the bonds and/or land acquisition, potentially delaying the start of construction and threatening the Authority’s ability to complete the Central Valley section by the federally imposed deadline of September 2017.

When asked about the potential impact of litigation on the Authority’s schedule, Chairman Dan Richard observed that "simply filing a lawsuit does not means they will win, nor if they do win does it automatically mean injunctive relief." In other words, the litigation may or may not delay construction in the Central Valley. It’s California, so there will always be lawsuits," Richard added with a chuckle.

The "Bookends" Approach

Chairman Richard’s approach is two-pronged. While supportive of the distant vision of linking the Southern and Northern portions of the state with a high-speed rail line, he sees a need to show signs of near-term service improvements in order to gain crucial political support of skeptical local officials and the public. The dollars spent on the "bookends" could have "an immediate and dramatic effect" he told us.

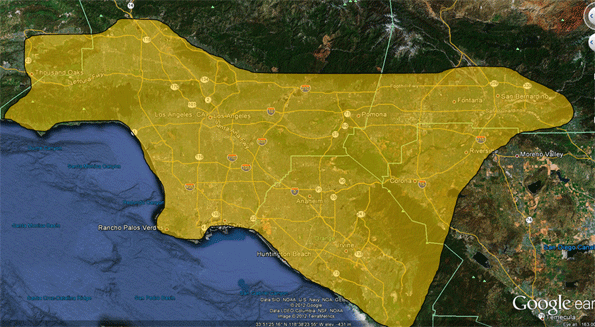

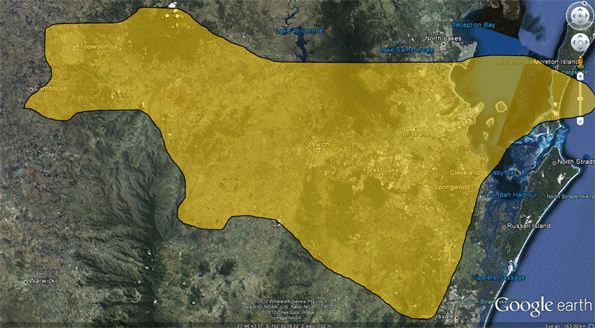

Improving the metropolitan "bookends" of the system will make it possible to increase the speed of local commuter trains and thus bring immediate travel benefits to large segments of California’s urban population. Will Kempton, chief executive of the Orange County Transportation Authority (OCTA) and chairman of the Independent Peer Review Group advising the High Speed rail Authority agrees. It will be a good investment whether or not the overall $68 billion high-speed rail project ever gets completed, he said. Sensing a promise of new money, planning and transportation agencies in Southern California and the Bay Area have thrown their support to the Authority’s "bookend" strategy.

The Long-Term Strategy

As for implementing the high-speed rail project itself, Richard is convinced that its various pieces will eventually fall into place, one step at a time. "What we’re doing is building a high-speed rail line," he told us, "that will connect to the existing tracks and allow passenger-only service between the town of Madera (north of Fresno) and Bakersfield. It will cut significant time off the trip from Oakland/Sacramento to Bakersfield.. At the same time we will be upgrading Metrolink from LA/Union Station up to Palmdale and we have our sight set on the next phase, which is Bakersfield to Palmdale. Once that gap is closed, we’ll have an intercity rail line from LA to northern California, albeit one with a couple of transfers, but we think that is when private sector investment will come in and help upgrade the entire line to full high speed rail. Even our critics agree that if we get to Palmdale, everything changes. We’re not that far away, in terms of either miles or dollars. … Richard summed up, "We took great pains to make sure the investment is not stranded. The point is that we have an effective beachhead for a true advanced passenger rail system."

Exactly how does the Authority propose to fund the $8-11B cost to close the gap from Bakersfield and the Central Valley to Palmdale and down to LA (assuming the project does not go over budget)? Richard remains serene and confident. "We will have about $4 billion of our bonds left," he said." They must be matched. We will be looking for federal funding, to be sure, arguing that this can help free up freight capacity, assist goods movement through the Central Valley and enhance the efficiency of ports. … We will also be pushing hard to look at other private sources…If all of that fails, we have the prospect of state cap-and-trade revenues."

These are heroic assumptions. Future federal support is highly uncertain. Congress, by eliminating Title V of the Senate transportation bill (the National Rail System Preservation, Expansion and development Act of 2012) from the final version of the surface transportation reauthorization (MAP-21) and by denying Administration requests for high-speed rail funds three years in a row, could not have sent a clearer message that states should not count on continued congressional funding of high speed rail, Transportation Secretary Ray LaHood’s bluster notwithstanding ("We will not be dissuaded by the naysayers in Congress…High speed rail is alive and well in America…The Administration is keeping high-speed rail on track…") "The President’s high-speed rail program is "a vision disconnected from reality," members of the Democratic-controlled Senate Budget Committee lectured Secretary LaHood at a recent hearing.

Private sector funding is equally problematic. "We see no evidence that private investors are taking serious interest in this project at this time," a financial consultant knowledgeable in public-private partnerships told us. As for cap-and-trade revenues, their use to bail out HSR is expected to meet with opposition from the state legislature, according to several sources.

For the backers of high speed rail, the implications are grave. Absent further federal funds and absent private capital, the State will be obliged to seek a fresh infusion of public money as early as 2014 if it is to continue pursuing its $68 billion train project. Will California voters be willing to approve new bonds for this venture, given recent surveys indicating dwindling popular support? Can the Governor and the Authority keep the faith alive by dangling a vision of a bullet train that few voters (and politicians) can hope to see deployed in their lifetime? There is reason to be skeptical.

Ken Orski has worked professionally in the field of transportation for over 30 years.

CA route map by Wikipedia user CountZ.