The latest local government elections in Queensland, along with the by election for former Premier Anna Bligh’s state seat of South Brisbane, may point to a fundamental shift in popular mood back in favour of growth and development. After many years of anti-growth policy paranoia, it’s a refreshing wind if it lasts.

Was the electoral storm that swept ‘Can Do’ Campbell Newman and the conservative LNP to power only a few weeks ago something more than a direct reaction to a failed state Labor government? Subsequent local government election results state-wide may point to a more fundamental shift in community attitude. Why? Because one month after a resounding rejection of the state government, voters once again lined up to sink the knife into incumbent mayoral candidates who have presided over needless bureaucracy, excessive red tape and anti-growth policies disguised in political or media spin.

Those who expected a bounce back to Labor from voters recognising the very large mandate of the new LNP state government were proven badly wrong. Even Labor’s stronghold state seat of South Brisbane, narrowly held by the former Premier at the last election, barely got over the line to Labor this time in a by election.

Is this a sign that anti-growth and anti development policies, manifesting themselves in all manner of precautionary principles, red tape and green tape and which effectively ground the Queensland economy to a standstill, are on the nose? Maybe it’s not just the Labor ‘brand’ but bad public policy per se which is being rejected.

The real economy – undisguised by the statistical support of the booming resources sector – has been suffering, with construction activity across the board falling to record lows, interstate migration and population growth slowing to record lows, and house prices and personal balance sheets under stress. Rising utility costs, partly or largely (depending on your view) driven by green-tinged policy settings, have hurt average families. New housing costs have risen and proven a barrier for a generation of young families wanting to enter the market without having to sacrifice everything in exchange for a mortgage they can’t afford. Overall, the people are clearly pissed off. And they showed it.

In Brisbane, Lord Mayor Quirk – a prominent anointee of ‘Can Do’ Campbell Newman – was returned with an increased majority. And elsewhere, pro-growth candidates replaced incumbents whose administrations had presided over growth in regulatory process with little by way of measureable outcomes. In Redlands, a reputedly notorious local authority in terms of its hostile attitude to growth and development, Mayor Melva Hobson was turfed out in favour of pro-growth candidate and new Mayor, Karen Williams, (Williams scoring 69% of the primary vote to Hobson’s 31%).

On the Gold Coast, pro-growth candidate and Chamber of Commerce President Tom Tait won resoundingly with 37% of the primary Mayoral vote. The next closest candidate was Eddie Saroff – a long serving Gold Coast Councillor and former Labor federal candidate, on 17.5%.

On the Sunshine Coast – another Council which became notorious for being difficult to deal with and consumed with red tape and pointless administrative process – the pro growth and pro business candidate Mark Jamieson (33%) scored more than double his nearest two rivals, each on 17%.

In Ipswich, popular Mayor Paul Pissale increased his majority, with almost 88% of the primary Mayoral vote. You would be hard pressed to find a more passionate, pro-growth and pro-development Mayor than Pissale, especially when it comes to his beloved Ipswich. This is a man who proudly proclaimed that he welcomed development and developers to his city.

In Cairns, another region fast developing a reputation for an economy strangled in anti-development red and green tape and excessive planning controls, prominent local business identity and pro growth candidate Bob Manning picked up 56% of the primary vote, well ahead of his nearest rival, the incumbent Val Schier on 20%.

The South Brisbane by-election result adds weight to the argument that this is part of a widespread and deep seated mood for change. Labor, in what is billed as a stronghold inner city seat, expected some solid bounce back as South Brisbane voters were encouraged not to give the LNP another seat in Parliament. They didn’t listen to the party line, and only one in three (33%) put the new Labor candidate Jackie Trad first. By contrast 38% of South Brisbane voters put LNP candidate Clem Grehan first. Labor had to survive on the preferences of the green vote, which drew 19.4% of the primary vote in that seat.

Now take these most recent results and put them back to back with what happened in the state election just over a month ago. The LNP picked up a staggering 50% of the primary vote state wide, giving them 78 of the 89 seats. Labor picked up just over one in four primary votes, at 26%. The Greens only picked up 7.5% – less than their result in the previous election. The Greens in fact were outpolled by Katter’s ‘Australia Party’ which scored 11.5% of primary votes state wide. (I’m not sure whether to describe Katter’s party as pro growth but its connections to pro development rural interests suggests it is).

That state election was a clear cut choice between a ‘Can Do’ Campbell Newman and a Labor machine which ran heavily on anti-development messages in its campaign, alleging that an LNP Government would be hostage to developers and hostile to the environment. There was no confusion in voter’s minds when they rejected the latter and firmly chose the former. You don’t get much more pro-growth than a candidate and a party which uses ‘Can Do’ as its rallying cry.

The point of all this is that the new political mandate for growth shouldn’t be dismissed as some isolated reaction to the past government’s failings. The community seem to be making their views clear: bring back growth, bring back economic prosperity, restore the state’s balance sheet and with it, restore some health to personal balance sheets. The anti-growth movement will never be silenced by majority views but hopefully in this clear message from the people, it will take a backseat and keep a low profile, for a while at least.

For Labor, aligning itself with anti-growth movements might prove even more damaging in the long run. Average workers on average wages left the Labor Party in Queensland in no doubt they were on the nose. It’s not just an issue of a damaged brand, and much more than a failed campaign strategy. If Labor stands in people’s minds as a party which objects to progress, which imposes punitive taxation on even humble endeavours, which is responsible for excessive intrusion of regulation into people’s lives, and which is hostage to fringe interest groups in a bid to win preference deals, it may be left in a political wilderness for a long time to come. Labor’s reconnection to working families and their values and interests is as surely the key to the revival of their fortunes, just as John Howard achieved and as Campbell Newman and a host of newly elected Mayors in Queensland have proven.

Ross Elliott has more than 20 years experience in property and public policy. His past roles have included stints in urban economics, national and state roles with the Property Council, and in destination marketing. He has written extensively on a range of public policy issues centering around urban issues, and continues to maintain his recreational interest in public policy through ongoing contributions such as this or via his monthly blog The Pulse.

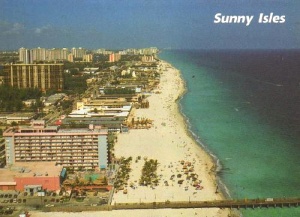

Brisbane photo by Bigstockphoto.com.