When’s the last time you heard some futurist or management guru suggest that in the future more of us will be working at the same desk doing routine tasks on a predictable working week schedule? No? That’s just one of many problems that advocates of limitless spending on public transport need to keep in mind in dealing with the issue of urban congestion.

Increasing urban congestion is said to cost the economy dearly and if Infrastructure Australia is to be believed, it will cost even more in the future unless something is done now. They warn the current estimate of a $13.7 billion annual cost will balloon to $53 billion by 2031.

Congestion is without dispute a handbrake on economic productivity but the range of solutions for reducing congestion range from the outright zany (see Elizabeth Farrelly’s suggestions for Prime Minister Turnbull as one example) to milder versions of zany. They all tend to be very expensive and many impose unacceptable compromises on our basic freedoms (such as proposals to ban cars from cities).

Increased investment in public transport is a feature of many proposed solutions for alleviating congestion. It is true that we have under-invested in public transport systems in past decades and it’s equally true that we’ve under-invested in private transport. Basically, we’ve cheered a rising population while passing the buck for funding and delivering the infrastructure needed to support that growth to future generations. Rising congestion levels are making it feel like crunch time now.

But there are valid questions about the capacity of public transport to alleviate congestion which are rarely getting asked. Rather than a magical silver bullet, there are a few things to keep in mind before you climb aboard the merry bandwagon of limitless investment in public transport…

The nature of work is changing. Public transport systems work best on a hub and spoke model of employment and commuting, built on predictable schedules designed around predictable commuter needs. Central business districts of very high employment concentrations, where people work in the same workplace from day to day and for the same hours each day, are ideal candidates for public transport. But increasingly this is looking like a 20th century model of work. Technology has been the primary driver of change, allowing more workplace flexibility and providing for increased location diversity. ‘Standard hours’ of work are being diluted and at the same time companies increasingly realise the high costs of ‘paper factories’ for administrative staff in costly CBD locations makes little sense. With this, the centralised nature of work is also being diluted and this is working against the centralised economic model that makes fixed public transport systems (especially rail) effective.

Society is changing. There was a time when commuting trips to work in central locations were mainly a case of getting there and getting home. Much has changed. A rising proportion of women in the workforce and how this has changed family responsibilities means that commutes to and from work are also often tied in with other objectives: dropping off or picking up school kids or children in child care is only a part of this (but one which is said to contribute to 20% of private vehicle traffic on the roads in peak periods during school terms). Add in to this the increasing propensity to shop less but more frequently (who owns a chest freezer anymore?) and to mix in pre and post work social or recreational appointments, and you have a very different pattern of commuting which public transport will struggle to service.

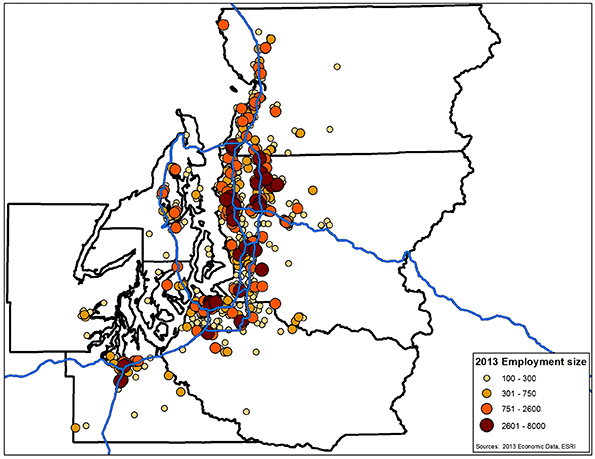

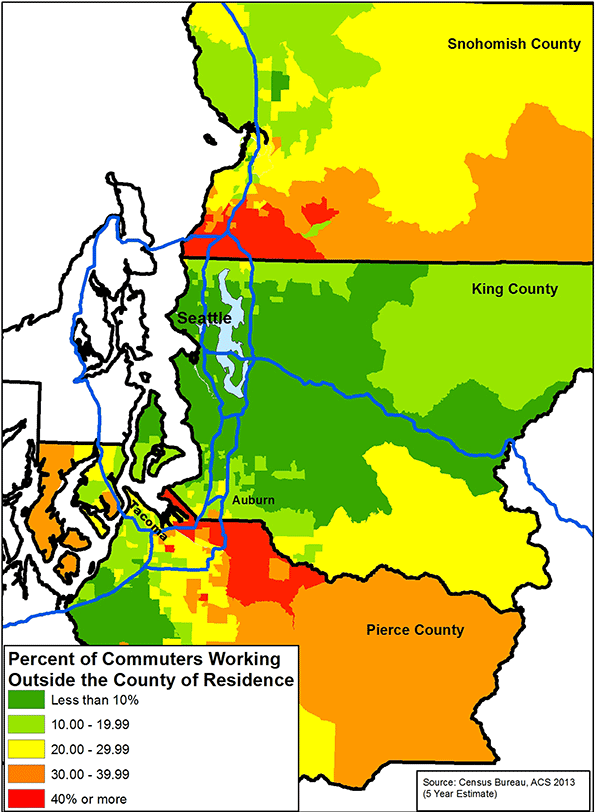

The suburban economy. A telling reality for proponents of increased public transport investment is that employment remains – and in some cases is increasingly – suburban by nature. Between 8 and 9 out of 10 of all jobs in metropolitan regions are suburban by location, and when you consider that the same proportion of residents in any metropolitan location are also suburban by residence, the problem of servicing this reality through public transport is apparent. In the last inter censal period, the proportion of metropolitan wide jobs located in the CBD actually fell in Brisbane (to 12.5%), while in Melbourne it remain unchanged (at 10%) and Sydney recorded a small rise (to 13.5%). The raw numbers of jobs in suburban locations are growing faster, as a rule, than those in CBDs. The cost of creating a public transport system designed around suburban home to suburban workplace commutes is beyond calculation. In Australia, we will be in flying cars like the Jetsons long before this happens.

The new and emerging economy. The way cities were designed – with concentrations of white collar workers in CBDs and with discrete areas set aside for industrial, retail or other specified activities – is no longer as important for new or emerging economies. Technology in particular means that physical place is less essential for connectivity to markets. Communication is less dependent on physical proximity. This doesn’t mean CBDs will lose their higher order function but it does mean that disruptive or emerging businesses, for which new technologies are more than just a novelty but a foundation, will have less need for the types of places offered by centralised business districts. They can locate in lower cost areas of the metropolitan area, and make use of the central business districts on occasion, rather than routine. Attracting and retaining these emerging types of businesses will also put the onus on suburban business centres to lift their game, but in many cases this isn’t difficult. Just think of any number of start ups or tech based companies you’ve read of recently and think about how many of these have been in non-traditional locations. Even when these businesses mature, their lack of interest in a CBD style presence doesn’t seem to change. Witness the many technologically innovative businesses in the USA or Europe, by way of example.

Where does this leave us with solutions for congestion? Ironically, increasing public transport investment designed to ferry people into and out of central business areas is unlikely to make much difference to metropolitan wide congestion. It can’t – simply because only a minority of jobs (between 10% and 15% in the case of Australia’s major cities) are in these locations. People with jobs in these locations may currently have relatively high rates of public transport usage already (often 40% plus) but imagine the cost of increasing this to 80%? The cost of getting there is incalculable for cities of our size, and in any way, it would only benefit 10% to 15% of the urban workforce. Ironically, the people most likely to benefit from this type of public transport prescription tend be much higher wage earners, living close to the inner city in highly valued real estate. (Have a look at this analysis from The Pulse a couple of years ago). Yet their higher capacity to pay is not reflected in most policy debate.

The reality is that public transport can only go so far in alleviating congestion. Social and economic change to the nature of work is changing the shape of employment decisions and has forever changed the nature of the commute. Public policy officials, urbanists and politicians who pretend that all that’s needed to ‘solve congestion’ is massively increased investment in heavy rail, light rail or dedicated busway networks are deluded: this thinking is rooted in nostalgic notions of work, unrelated to the future of work.

And as if to demonstrate the fact we should not expect better from our various governments, when a technological innovation comes along that promises to realize the long held dream of ride sharing and increased persons per vehicle – which if widely embracedwould go a long way to solving congestion at no cost to taxpayers – governments stand in the way. It’s called Uber. Go figure.

Ross Elliott has more than 20 years experience in property and public policy. His past roles have included stints in urban economics, national and state roles with the Property Council, and in destination marketing. He has written extensively on a range of public policy issues centering around urban issues, and continues to maintain his recreational interest in public policy through ongoing contributions such as this or via his monthly blog The Pulse.