Today, Beijing seeks to balance strong economic growth and soaring prices amidst a severe global crisis and debt turmoil in advanced economies. The challenge is colossal – to provide urban space for more than 600 million people in the coming decades.

For months, the famous hedge fund wizard, James Chanos, has been predicting a severe Chinese property slump. As he puts it, “Dubai times 1,000 – or worse,” with the “potential to be a similar watershed event for world markets as the reversal of the U.S. subprime and housing boom.”

The contrarian investor Chanos made his fortune on Wall Street by foreseeing the collapse of Enron and other high flying companies whose stories were “too good to be true.” He is not the only skeptic on China, but certainly one of the most prominent and articulate. And yet, China’s real estate market is very different from those of the U.S. or Dubai.

In Dubai, the problem had to do with too much leverage. In China, consumers buying residential properties are required to put down 30 percent before taking out a mortgage. For a second home, the down payment is 50 percent, irrespective of their net worth. Home purchase is predicated on affordability.

In the pre-crisis U.S., perverse incentives were magnified by low interest rates, sometimes minimal down payment and loans to those with poor credit histories. Excessive debt was sliced, repackaged and securitized into mortgages. Banks and ratings agencies engaged in unethical conduct. Appropriate regulatory oversight was absent.

In the long-run, the containment of rapid price increases is vital for China’s economic growth and social cohesion. In the short-run, volatile price fluctuations are difficult to avoid in the large urban centers. These large agglomerations are evolving into “global cities”, which are driven not just by local conditions, but by global trade and investment.

Soaring prices

In “China bubble” predictions, Chinese property markets are typically portrayed as unitary or homogeneous. Yet, there is huge variation among cities and regions. In 2009, the urban GDP per capita was highest in Shenzhen reaching almost US$13,800 USD, whereas in Hefei it was about US$6,100.

Until recently, the concern for the soaring prices in the property markets has been focused primarily on the high-end segment of the first-tier cities. Since the 1980s, the economic ripple effect of the successful first-tier cities – such as Shenzhen, Beijing, and Shanghai – has been spreading into new generations of Chinese cities.

By the early 2000s, second-tier cities – from Suzhou and Shenyang to Chengdu and Chongqing – attracted significant attention with investments from global corporate giants. Third-tier cities – from Ningbo and Fuzhou to Wuxi and Harbin – have been following in the footprints, while inspiring still others, such as Kunming and Hefei.

Yet for the most part soaring prices characterize primarily residential properties – almost exclusively the high-end segment of the most prosperous first-tier cities.

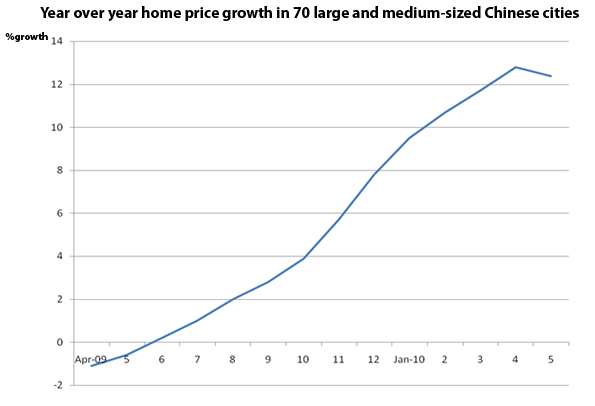

In March, property prices in 70 Chinese cities soared by a record 11.7 percent from the previous year. In response, the government rolled out a series of measures to curb the domestic housing market amid concerns over asset bubbles.

In early May, the People’s Bank of China raised the reserve requirement ratio for major banks by half a percentage point. Property stocks were expected to face further decline. Following Beijing and Shenzhen, the Shanghai municipal government released regulations for the property sector to curb housing speculation and soaring prices.

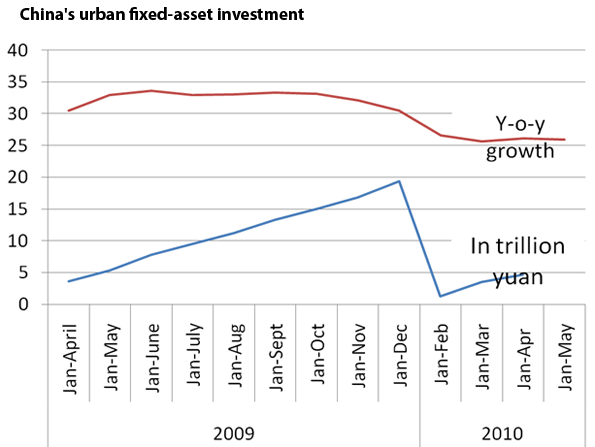

Some observers worried that tightening policies may deter property developers from starting new projects and purchasing land, thereby cutting the supply and pushing up prices next year. And yet, despite these measures, housing prices rose 12.8 percent in April from a year earlier. At the same time, China’s urban fixed-asset investment increased by 26.1 percent year-on-year to $684.63 billion. The growth rate was 4.4 percentage points lower from the same period of 2009.

As public concern over “skyrocketing housing prices” continued to simmer, the real estate tycoon Ren Zhiqiang was hit by a shoe at a forum in Dalian. The attacker was fuming over soaring housing prices.

Last month, home prices in 70 Chinese cities rose by 12.4 percent year-on-year. The growth rate was 0.4 percentage points lower than in April, as property sales in first-tier cities (including Beijing, Shanghai and Shenzhen) contracted following the string of government measures. New home prices rose 15.1 percent year-on-year, down 0.3 percentage points from April.

In a bid to curb soaring prices, the government has tightened scrutiny of developers’ financing, curbed loans for third-home purchase, raised minimum mortgage rates and tightened down-payment requirements for second-home purchases.

By early summer, new home sales in Beijing were down 70 percent. Property transactions in Shanghai slumped around 70 percent and in Shenzhen by 62 percent month-on-month in May.

Why have prices soared so frantically and what could be done about it?

Toward new developments and new business models

In the West, the great urban centers – from Paris to New York City and Tokyo – evolved into great metropolises in a century or two. In China, the first-tier cities – such as Shenzhen, Beijing, and Shanghai – are morphing into global cities in barely decades.

Understandably, the residents of the first-tier cities would like to own an apartment in their home city. However, these cities also attract the wealthy across China, prosperous investors in East Asia and multinational property companies worldwide.

Additionally, the high price-to-rent ratios have been driven by speculation, the desire for long-term investment, and few investment instruments.

Even buyers contribute to soaring prices. To facilitate the marriage of their son or daughter, parents are often willing to devote their savings to real estate. As the young couple and their parents put income and savings into a purchase of a single apartment, excessive prices are driven even higher.

In addition to great demand, the soaring prices reflect supply dilemmas. Currently, residential real estate development is geared to high-end and high-margin properties, which ensure a significant cash flow for cities. In the leading cities, the direct and indirect GDP contribution by real estate can amount to some 25-35 percent of the GDP; in other cities, this contribution is relatively higher. Ironically, luxury developments support local incomes, which maintain economic growth nationwide.

As long as high-end real estate offers high margins where affordable housing does not, regional governments, which possess the land rights, have an incentive to prioritize luxury projects.

The government seeks to sustain real estate market development and thus to support growth critical for China’s economy. It also seeks to ensure affordable housing vital to Chinese people. As debt problems are escalating in the West, reconciling these goals – economic growth and affordable housing – poses a difficult challenge.

A shift towards affordable mass-market – reportedly only 10 percent of total residential sales – is critical. In the current business model, high margins come from a very narrow high-end segment of the market. This made sense in the early days of Chinese real estate when only few wealthy people could afford a home.

Today, far more Chinese are able and willing to acquire a home. A new era requires a new business model, which can be based on the broad middle-class segment of the market.

Conclusion: China is not Japan déjà vu

In China’s property markets, some argue that the risks are now so great that a decade of little or no growth, as Japan experienced in the 1990s, can no longer be dismissed. They see parallels with Japan in the late 1980s, when authorities responded to the export slump caused by the revaluation of the yen after the 1985 Plaza Accord. As Tokyo adopted a low interest rate policy to boost an expansion in domestic demand, it also created conditions for a massive economic bubble.

Yet, contemporary China’s situation is very different. First of all, in China, there remains a large shortage of residential property that meets new living standards.

In Japan, property price increases were more than 30 percent in the latter half of the 1990s. In China’s prosperous coastal cities, they have been around 12 percent in 2003-2009.

In Japan, the health of the banks deteriorated rapidly with the asset bubble. In China, the share of non-performing loans declined from almost 20 percent to less than 2 percent in the 2000s.

In Japan, the asset bubble occurred after the eclipse of the high-growth era. Instead of a potential growth rate of 3-4 percent, China, assuming stability in the international and domestic operating environment, may enjoy relatively high growth for another decade or two. In such circumstances, even rapid price fluctuations in the first-tier cities can be tolerable, even if they are not preferable.

Ultimately the difference between Japan and China is reflected by demand. Japan in the 1980s was already highly urbanized and its city population was plateauing. In China, the situation is very, very different.

Today, there are some 360 million urban residents in China. In the next three decades, the figure is expected to grow to 970 million. What Beijing is trying to achieve is unique in history – to create urban space to more than 610 million people, within a single generation.

In such an environment, periods of overheating will occasionally be accompanied by dramatic price increases.

China, the urbanization rate is about 45 percent, whereas in Japan and other advanced countries it is more than 80 percent. As these nations reflect very different levels of economic development and different levels of individual prosperity, their real estate markets are different as well.

Despite its rapid pace of expansion, China’s real estate is still at a very preliminary stage. The marketplace is so colossal that there are no precedents, no simple models.

Yet the prospects for a robust growth remain intact. The key will be not to allow that growth to become threatened by a property bubble – while providing affordable housing for the rapidly-expanding new middle-class.

Dr. Dan Steinbock is Research Director of International Business at India, China and America Institute (USA) and Senior Fellow at Shanghai Institutes for International Studies (China). The brief is part of the author’s ongoing project on emerging megapolises worldwide. A highly abbreviated version of the brief has been published by China Daily, China’s leading English-language daily in May.

Photos and Illustrations: Dan Steinbock and China’s National Bureau of Statistics