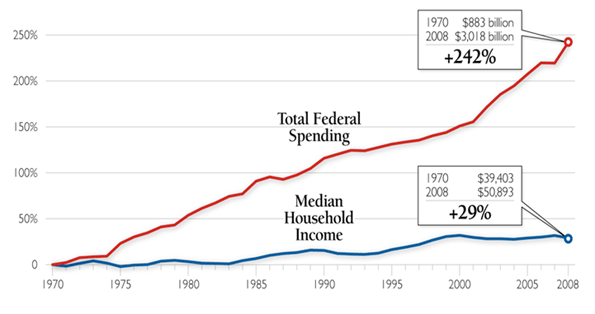

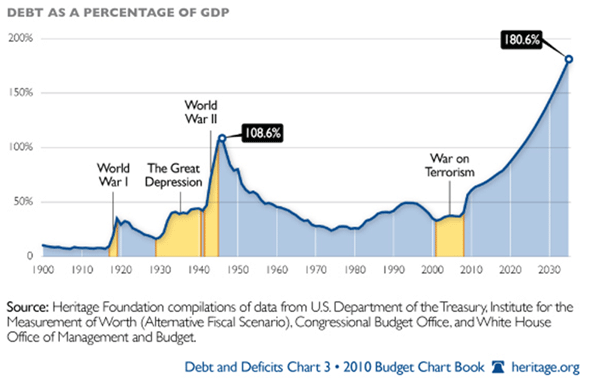

The federal debt climbed above $13 trillion this month. An easier way to define the national debt is to comprehend that we each owe more than $39,000 to the Chinese, Japanese, and Arabs of the Persian Gulf. The budget deficit will exceed $1.5 trillion this year and forty-seven states are running deficits. California has a $19 billion deficit and its legislature’s landmark response was to pass a law banning plastic bags. Our cities are in worse shape. The former mayor of Los Angeles, Richard Riordan, says that a bankruptcy by that city is inevitable. At the same time, the United States’ Congress voted themselves a 5.8% pay increase. It is no wonder why Americans are nervous.

Americans are stressed out because of debt, according to an Associated Press-GfK poll. They are trimming their debt at the fastest rate in more than six decades, according to the Federal Reserve. The average amount owed on credit cards is $3,900, the poll said. That’s down from $5,600 last fall and $4,900 last spring. Household debt fell 1.7 percent last year to $13.5 trillion, according to the Fed. It was the first annual drop, based on records going back to 1945. As Americans get their own house in order, the approval rating for Congress has fallen to an all time low. The public will likely make them pay for their angst in November.

The American people are about a year ahead of the politicians. The spending by Washington, Sacramento, Los Angeles, and by politicians in general, is unsustainable. The people understand that it must be changed. As Senator Tom Coburn (OK) told me last week, either we change our ways or they will be changed for us. Leaders like Senator Coburn will begin The Great Deconstruction. The nation can no longer afford the government it has created.

The Department of Energy was created by President Carter in 1977 after an OPEC embargo caused gas lines and rationing. In 1977, America imported 33% of its oil. The DoE’s goal was to eliminate our dependence on imported oil. The DoE budget for 2010 was $26.4 billion. It employs 116,000 workers. We now import 66% of our oil. America can no longer afford such an inefficient bureaucracy. Bureaucracies like the DoE that have lost sight of their purpose must be deconstructed.

Senator Coburn is preparing legislation to rescind $120 billion in 2010 spending by rescinding 2010 budget increases, consolidating 640 duplicative governmental agencies, returning unspent appropriations and cutting wasteful spending. A few examples:

- Congress has a discretionary budget of $4.7 billion per year. They voted themselves a 6% increase in 2010. Coburn wants this increase rescinded for a saving of $250 million.

- The Department of Education spends $64.2 billion per year. They spend $1 billion each year administering 207 separate programs at 13 different federal agencies to “encourage” students to take math and science.

- The Department of Agriculture owns 57,523 buildings. More than 4,700, valued at $900 million, are vacant. Despite this vacant space they spend $193 million per year renting an additional 11 million square feet.

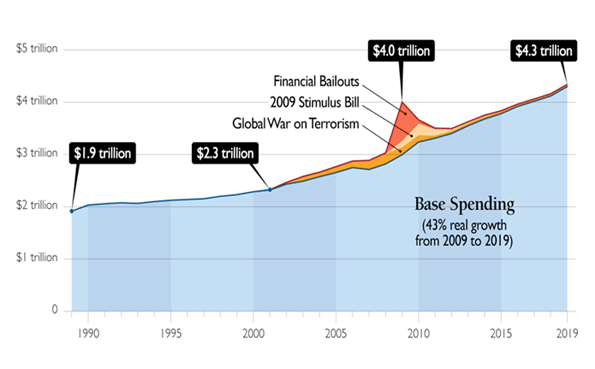

Our politicians have perfected the art of spending money, or as we now know, wasting money. Last year, they loaded spending bills with $11 billion of earmarks – after spending $860 billion on a Stimulus Bill. A new breed of politician, like Senator Coburn, will begin the long process of deconstruction.

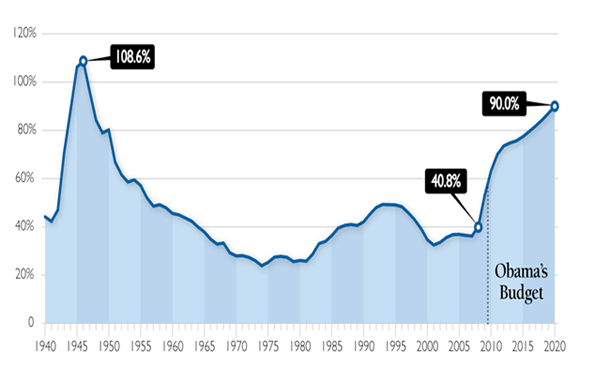

There is precedent for deconstruction. In 1945, federal spending ballooned to $106 billion, $93 billion of which was for defense. The deficit jumped from $40 billion in 1938 to $253 billion in 1945. A Democrat President and a Republican Congress established the Commission on Organization of the Executive Branch of the Government in 1947. President Truman put a former Republican President, Herbert Hoover, in charge. It became known as the Hoover Commission. It created the structure of government that exists today and generated savings of $7 billion at the time. A total of 273 recommendations were presented to Congress in a series of nineteen separate reports. A 1955 study concluded that 116 of the 273 recommendations were fully implemented and that another 80 were mostly or partly implemented. By 1949, the federal budget had fallen to $40 billion.

It will come to be known as The Great Deconstruction because it must occur at every level of government. Federal spending is unsustainable. Moody’s is already speculating that we may lose our AAA rating. The states are in crisis with 46 in deficit. The press is referring the California as a “failed state” and “our Greece”. The $860 billion Stimulus Bill sent approximately 30% to the states to support their public employees. But it was a one-year fix. This year, the states are burning through their reserves and next year, they will be forced to cut services, raise taxes, or both. Connecticut, the wealthiest state on a per capita basis with personal income of $54,397 in 2009 (Department of Commerce) saw its Fitch rating lowered from AA+ to AA. Connecticut needs to borrow $956 million to close a budget gap this fiscal year and it borrowed $947.6 millionto cover last year’s deficit.

The cities are no better off with many states raiding their reserves. Many cities are exploring municipal bankruptcy, Chapter 9, as a way out of unsustainable contracts. The Great Deconstruction will take a decade or more. Like the Hoover Commission before it, this process will transform the role of government, and the image of government as it transforms the cost of the people’s business.

***************************************************

The Great Deconstruction is a series written exclusively for New Geography. Future articles will address the impact of The Great Deconstruction at the national, state, county and local levels.

Robert J. Cristiano PhD is the Real Estate Professional in Residence at Chapman University in Orange County, CA and Director of Special Projects at the Hoag Center for Real Estate & Finance. He has been a successful real estate developer in Newport Beach California for twenty-nine years.

Other works in The Great Deconstruction series for New Geography

The Great Deconstruction :An American History Post 2010 – June 1, 2010

The Great Deconstruction – First in a New Series – April 11, 2010

Deconstruction: The Fate of America? – March 2010