Every generation seems to be lionized by the press with the observation that the values of the new group are not that of their parents, thank goodness. They don’t have the serious hunger for possessions, the terrible acquisitiveness for material things that define their parents’ generation. Rather, as seen by the reporter, they have loftier views of society, generally the views of the reporter or the views that the reporter wishes to have us believe they hold. One recalls how the baby boomers were “not like us”. They were going to live on the land somewhere in the high sierras making sandals and candles. Some years later when it was revealed that the Pentagon was paying two thousand dollars for special toilet seats, the question among boomers was in what colors were they available.

Today much has been made of the sharply varying characteristics of the Millennial generation. During the recession and its prolonged twilight recovery we had to keep asking: “is it really a structural change we are seeing or just cyclical?” We have found in most cases when some see harbingers of dramatic changes in societal values it is often just economic realities at work. Wait for the data is a great admonition in such cases.

A recent Current Population Report from the Census Bureau sheds considerable light on the topic. The powerful tool employed compares young adults in 1975 to those in 2016 roughly 40 years apart. The overarching observation is that the younger working age generation today appears to place more emphasis on two of the four markers of adulthood – education and a job – before the other recognized attributes of adulthood such as living separate from parents and family formation. Economic security appears to be the dominant driver of behavior. Given that they were exposed to a weaker economy than their forebears– wealth lost, jobs lost, college debt, home values and investments declining – it seems a very realistic strategy.

Some of the contrasts with the past are stark:

• Of the four markers of adulthood 45% of the young adults in 1975 had those attributes; by 2016 it had fallen to 24%. In 2005 those markers were the predominant living arrangement in 35 states; by 2015 only a decade later, post-recession, the number of states with most of young living independently dropped to just 6.

• More young adults today, 18 to 34, are living with parents than with a spouse.

• More than half of younger millennials, 18-24, live in their parent’s home.

• Fewer than two-thirds of older millennials, 25-34, live independently.

• One in four of the 25-34 group are neither in school nor working.

Many of these attributes seem to be cases of full societal participation delayed, rather than dismissed. The report finds marriage levels are about the same by age 40 between the current and the past 1975 generation. The difference is, if you will, delayed adolescence. About 80% of young persons were married by the age of 30 in 1975 the same percentage today isn’t reached until age 45.

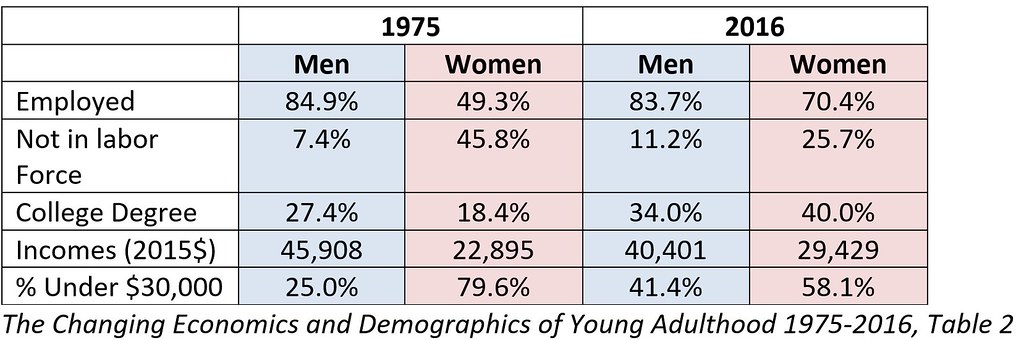

What is dramatically revealed in the document are the sharp divergences between the trends among men and women in the period. Young women are seeing significant economic gains today in contrast to 1975 while men have experienced limited progress, or even decline. Some of the contrasting experiences are summarized in the table below:

Characteristics of Young Adults Aged 25-34

There are really three stories here: the rising circumstances of women; the very limited improvements, if any, among men; and the dramatic contrasts between the groups over time.

• Women out of the labor force have declined from 46% to 26%. Men out of the labor force have grown from 7% to 11%.

• Women have risen from about 50% participation in the labor force to almost 75%, with 40% with college degrees today vs 18% in 1975, and with incomes shifting out of the lowest income categories and overall incomes rising significantly.

• Among young men, aged 25 to 34, in 1975, 25% had incomes below $30,000 per year, in 2016 dollars, rising to 41% below $30,000 in 2016. The percentage of men with college degrees has risen somewhat from 27% to 34%, but most significantly, incomes on a constant dollar basis have declined about 10%. Note also that women in the age group now have a greater share with college degrees than men; 40% vs 34%.

• Importantly, a substantial share of women has left the lowest income group while a similarly significant share of men has joined it.

• With all these gains, women’s incomes are still below men’s, substantially because women have moved from lower into middle income categories but not yet joined the higher income levels.

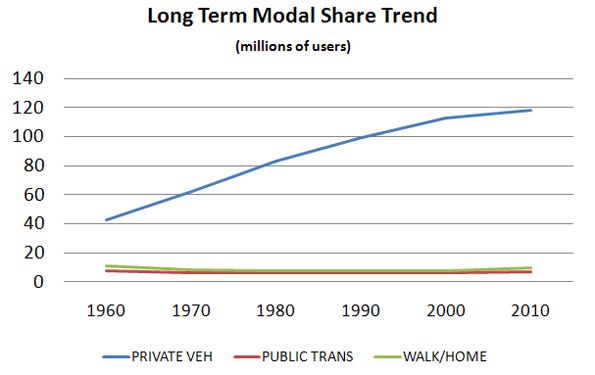

Are these changes economically based or values driven? The massive economic pressures on young males would have immense explanatory power. Their delayed ownership of vehicles, the postponement of separate living seems a rational response to their circumstances. Maybe rather than criticizing them, they should be appreciated today for exercising good judgment.

At the same time, the value changes recognized in the Census study seem to say that the measure of adulthood today emphasizes having completed one’s education and having obtained some degree of job security. These appear to come first, driven perhaps by the harsh realities of the last decade’s job environment which explains the delays in two factors historically linked to adulthood: living separately from parents; and marriage. These are now pushed into secondary, later stages in the life cycle.

Going forward the societal implications of these new patterns may be more significant than reporters ever estimated. Delayed job experience and exposure to the work environment may affect the job prospects of many and generate societal losses in skilled workers crucial to national productivity. As mates and parents their delayed relationships will be different than their parents’ world with impacts we can only guess at in terms of their relationships to each other, their children, and the greater society.

Alan E. Pisarski is the author of the long running Commuting in America series. A consultant in travel behavior issues and public policy, he frequently testifies before the Houses of the Congress and advises States on their investment and policy requirements.

Photo: ITU Pictures, via Flickr, using CC License.