As part of its annual Survey on American Fears, Chapman University has tried to identify what Americans fear the most. A team of professors and students teamed up to retool last year’s survey tool and dig up American’s deepest horrors. In total, a random sample of 1,500 adults across the country were asked about 88 different individual fears, in which they were to rank questions accordingly. Last year Americans were worried about walking alone at night and identity theft. But with the presidential elections just around the corner, it wasn’t surprising to see that corruption of our own government officials topped this year’s results.

Sociology of Fear

Nobody has ever cracked the code of human emotions. Our feelings are rooted within the depths of our physiology, but our cheers and screams are also products of our environment. Put in sociological terms, “fearfulness in varying degrees is part of the very fabric of everyday social relations”. This is bad news for those who thought the pursuit of happiness would be all fun and games.

Director of the Fear Survey Chris Bader recruited a group of interdisciplinary students to join the semester long course to help retool last year’s survey and to provide fresh perspective on what American’s Fear. But when the student researchers involved in the project (including me) arrived at the first class of Sociology of Fear, we weren’t completely aware of what would be a grueling month of debate, passion, and even tears.

Our class conducted multiple rounds of survey testing with friends, family and strangers to get feedback on additions made to last year’s survey tool. The most common fear amongst us twenty something college students facing the brink of graduation was “not living up to our potential”, and we considered this when evaluating the current state of American fears.

Rapid communication and transfer of information creates the perception that our peers are having more fun and being more productive than us, and FOMO (Fear of Missing Out) was brought up numerous times during discussion. But our personal explorations did not interfere with the macro-level research conducted for the project, and in the end, the fears that rose to the top of the list were cross-generational. After all, the survey was on American fears, not millennial anxieties.

The course was a growing experience, but it was the work of the research faculty and project leaders that transformed this experience into excellent insights on the current American situation.

Biggest Fears Today

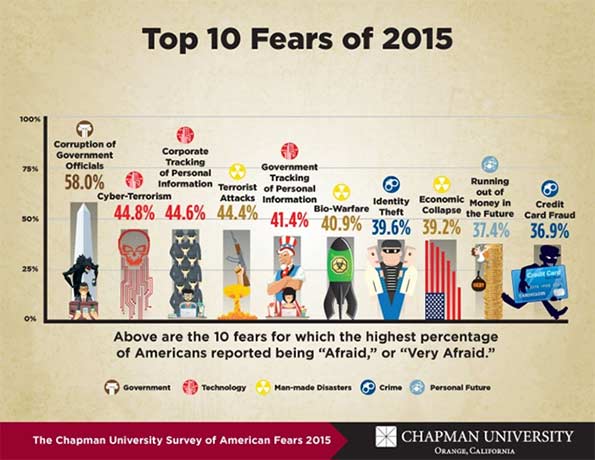

The survey explored four categories of fear: personal fears, natural disasters, paranormal fears, and drivers of fear behavior. The top American domains of fear averaged to be man-made disasters, technology, and government. Given the political transformations and technological developments taking place today, the results seem spot on.

In order of most feared to least, the environment, personal future, natural disasters, crime, personal anxieties, daily life, and judgment of others came in next on the list. Makes sense – I’m sure most of us have some concern about how we’re perceived by others, but this sentiment doesn’t quite stack up to a 8.0 earthquake or creepy government spying.

As for the top individual fears, 58% of respondents were afraid or very afraid of corruption of government officials. Perhaps Americans are on to some of the fishy things going on in Washington at the moment, or are simply sucked into the negative rhetoric commonplace in some opinion outlets. Meanwhile, only 30% of Americans are afraid or very afraid of global warming impacting their lives.

Following behind fear of government officials, 44.8% of Americans are afraid or very afraid of cyber terrorism. 44.6% are afraid or very afraid of corporate tracking of personal info, and 44.4% of terrorist attacks. 41.4% where afraid or very afraid of government tracking of personal info, and 40.9% of bio-warfare. The remaining top fears surrounded financial and personal issues, with identity theft coming in at 39.6%, economic collapse at 39.2%, running out of money in future at 37.4%, and credit card fraud at 36.9%.

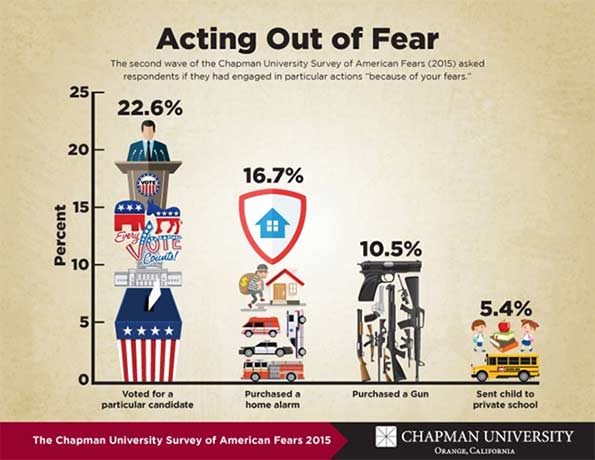

The survey also found that these fears are actually driving our actions. Fear has the strongest impact on our voting patterns. About one third who have an above average fear of government reported having voted for a particular candidate due to their fears. Even more alarming is the fact that “of those respondents who have an above average fear of the government, over 15% have purchased a gun due to fear.” Eight percent of people with an above average fear of the government send their children to private school out of fear.

As if gun control and education reform weren’t complicated enough, we can say that emotions will play some role in how policy is shaped in the coming years.

A society of hope or fear?

That fact that Americans fear government and technology is not surprising, given the individualist basis on which our nation was founded and the exponential technological growth we’re experiencing today. The Internet is forcing institutions and businesses to be increasingly transparent in everything from product sourcing to internal communications, and the watchdog power that citizens now have is both empowering, and frightening.

It’s easy to be blinded by fear, as our emotions are the most mysterious, yet powerful forces behind our decisions. But for every 58% who are afraid of government corruption, there is 42% who isn’t. For every 44.4 percent who are afraid of terrorism, there is 55.6% with no worries. Surely, there are preventative benefits that come with healthy skepticism and insecurity, but too much diminishes any hope for societal progress. Can we keep this in mind as we go about our business, citizenship, and personal lives?

The things that make us afraid can be dealt with. Some of them are opportunities, others are threats, and a good deal of them are complex issues and events that require brave souls to challenge them head on. This being said, we can all use a little inspiration to give us light in the face of darkness.

Nelson Mandela told us quite simply, “May your choices reflect your hopes, not your fears.” Emerson’s advice was a bit more menacing, perhaps more appropriate given the nature of this survey. “Always do what you are afraid to do.”

Charlie Stephens is a researcher at the Chapman University Center for Demographics and Policy, and an MBA candidate at the Argyros School of Business and Economics at Chapman University.He is also a regular contributor to the creative business site PSFK.com and the founder of substrand.com, a social awareness site that helps people, businesses, and communities understand their cultural environments and connect in new grounds.

Photo: “Actress-fear-and-panic” by MyName (Bantosh) – self-made, taken in course of professional work. Licensed under Wikimedia Commons.