Austin has enjoyed healthy growth during its 150-year history. As a rule of thumb, its population doubles every 20 years, and has done so since it was founded. It continues to grow at a healthy clip: from a population of 345,000 in 1980 to 656,000 in 2000; the Census Bureau estimates it had nearly 750,000 residents in 2008.

But if the city of Austin has grown briskly, its suburbs have exploded. Williamson County to its north was the sixth fastest-growing county in the United States between July 1, 2007 and July 1, 2008. Hays County to the south was the tenth.

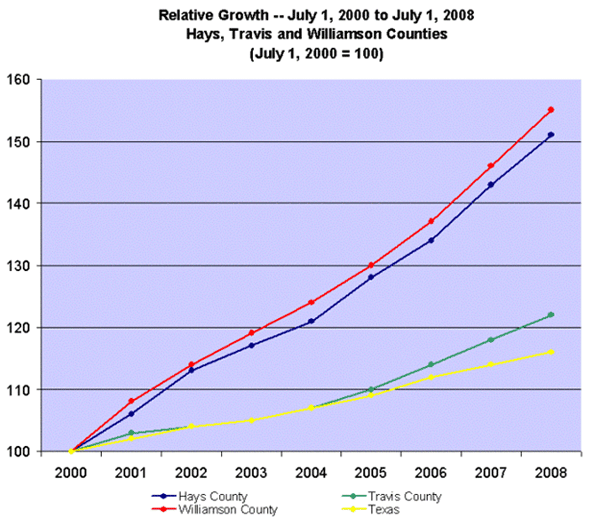

This is not a recent development. Williamson and Hays Counties have outpaced Travis County (Austin) and Texas for years:

The figures for individual suburbs reflect this spectacular growth:

- Between 1990 and 2007, Round Rock, ten miles north of Austin and home to Dell Computers, tripled from 31,000 to almost 100,000; its population grew by 50% between 2000 and 2007 alone.

- Pflugerville, just south of Round Rock, grew from a tiny village of 4,000 in 1990 to 34,000 in 2007.

- Cedar Park and Leander grew tenfold and sevenfold, respectively, between 1990 and 2007.

The scale of rapid growth is noteworthy, but the distribution of growth is hardly unique. After all, American cities have been suburbanizing for the last 60 years (and in some cities, for much longer). Austin’s suburbanizing growth merely mirrors the national trend.

But Austin’s growth evinces another pattern. As Austin and its suburbs have grown, families with children have left central Austin for its fringes, ceding central Austin to singles and couples without children.

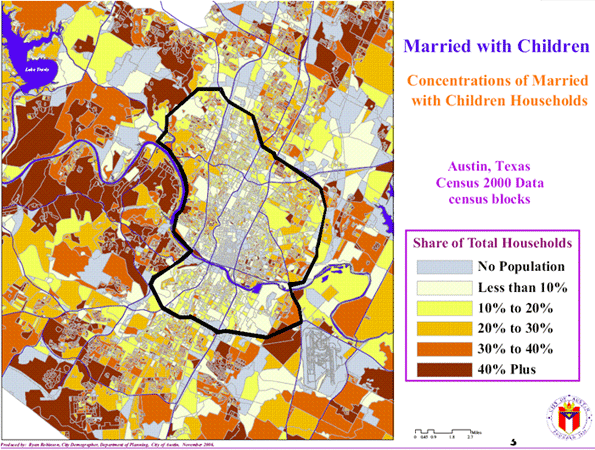

Central Austin is typically defined as the area urbanized by 1970, delineated by a perimeter of highways and lakes. But there’s an alternative definition: Central Austin is where the families with children are not.

The map below tells the story. It depicts, using 2000 Census data, the percentage of households consisting of married couples with children. Darkly-tinted regions have a relatively high percentage of such households; lightly-colored regions, relatively few. The area bounded by the heavy, black line – the lightly-tinted region in the center of the map – is central Austin.

This map excludes the suburbs in Williamson and Hays Counties. Needless to say, these cities would also be colored brown and deep-orange. For example, 45% of Cedar Park’s households in 2000 consisted of married couples with children. In Pflugerville, the figure was 48%. Over the last few decades, Austin has sorted itself into two cities: suburbs populated by families with children, and a central core populated largely by singles and childless couples.

Why?

This might seem a trite question at first blush. This pattern has repeated itself in one American city after another for many decades.

But Austin’s case is interesting because many standard explanations do not hold. Austin’s families have not had to flee the central city to escape crime, or dense, overcrowded neighborhoods, or failing schools, or the pollution and blight of old, abandoned industrial sites. Nor have they had to abandon the central city in search of jobs.

Austin historically has had a low crime rate with one of the lowest homicide rates in the country. And many of those crimes occur outside the central city. Austin’s slums are not located in central Austin, but in the aging suburbs just north and southeast of the urban core. Central east Austin – where African Americans and Latinos were banished for much of Austin’s history – was, and to some extent remains, an exception. But even that area has gentrified rapidly in recent years. And, in any event, neither east Austin’s problems nor a racist desire to avoid people of color can explain the flight of families from the historically “whiter” parts of town.

Central Austin certainly has plenty of bad schools. But it also has plenty of good schools, and a liberal transfer policy. Moreover, many of the central schools began to deteriorate after they were abandoned by middle-class families. Thanks to declining populations of children, the Austin school district has been forced to close several small, neighborhood elementary schools, even as it strains to add classrooms to the burgeoning suburbs. Austin includes many of its suburbs – it grows rapidly through annexation – and AISD covers these.

Families also did not have to flee central Austin to escape dense, overcrowded neighborhoods. The typical central Austin neighborhood is no denser than a typical suburban neighborhood. Most central Austin neighborhoods consist almost entirely of single-family residences. Indeed, in some, nearly 90% of the residential acreage is set aside for single-family housing, with multi-family developments relegated to busy streets. And yard sizes in suburbs are frequently little larger than the yards in the central neighborhoods.

Nor did families flee central Austin in a quest for green space. Austin’s great parks are concentrated in its core. These include Zilker Park – Austin’s equivalent of central park; Barton Springs, fed by springs bubbling up from the Edwards Aquifer; Lady Bird Lake, neé Town Lake; and more green belts than a die-hard hiker could cover in a summer.

Central Austin has no pollution or industrial blight. Austin has never been a manufacturing town. Its employment base has always been the University of Texas, the state government and, more recently, high tech.

The high-tech job growth has blossomed in Austin’s suburbs. Austin styles itself “Silicon Hills,” and virtually all high-tech jobs have spring up in the rolling country west and north of the downtown. But the addition of jobs to the periphery does not explain why families have been abandoning the central city. Austin’s core has not only retained its jobs, it has seen healthy growth. A recent Brookings study estimates that central Austin employment grew by almost 13% between 1998 and 2006 According to the Brookings study, the number of jobs more than 10 miles from the CBD increased by 77,523, or 62%. Obviously, this was incredible growth. But this does not explain why families abandoned the central core when it, too, was adding jobs.

In the end the key reason people have been moving to the suburbs lies in a mundane reality. Austin families have been moving to the suburbs because the suburbs have bigger, better and cheaper houses.

Austin’s inner neighborhoods may be packed with single-family housing, but they are small, old and increasingly expensive. The central neighborhoods were built before 1970 and, in most cases, before 1960. The houses are usually no more than 1200 or 1400 square feet. And these houses are expensive (for Austin) and often fixer-uppers to boot.

By contrast, the suburban stock is much newer and larger. Between 2000 and 2006, for example, the average new home in Circle C, a prominent suburb to the south, had 3,965 square feet; the average new home in Steiner Ranch, a western suburb had 3,915 square feet. And these houses were and are much cheaper than central city houses. One might find a 3,000 square-foot home in the suburbs for $250,000. The same home in central Austin might cost $750,000. Many suburban subdivisions have much smaller homes, of course, but a middle class family only able to afford an 1,800 square foot house in the suburbs is not likely to pay $400,000 for a smaller house in central Austin.

Families want space, and the central housing stock is either too small or too expensive. This basic reality has transformed Austin into essentially two largely successful cities: a central core left to small households and suburbs that offer either larger housing, or smaller housing at much cheaper prices.

This trend may have been slower if developers had been allowed to continue replacing small bungalows with larger, more modern houses. But this trend prompted an outcry from central Austin residents, who pushed the city council to enact a “McMansion” ordinance to “protect” central Austin neighborhoods. The title was a clever bit of marketing. The word “McMansion” evokes an enormous, pretentious structure – and who wants that? But Austin’s stringent ordinance takes aim at much more modest homes. Depending on lot size, a home with an attached two-car garage may be limited to 2,000 square feet, smaller than the typical new American home. The ordinance imposes other complicated limitations, turning modest home additions into a complicated, extensive ordeal. A homeowner who wants to add a second story, for example, must ensure that the second story fits within an elaborate “building envelope” – a complicated calculation unless the addition is centered in the lot – and new setback lines calculated as a rolling average of neighboring setbacks. (Incidentally, the new setbacks and square-foot limitations have all but eliminated granny flats.) The only option for adding a significant amount of new space is often the construction of a basement buried completely below grade; basements do not count against the square footage limits.

Austin’s McMansion ordinance will ensure that its central Austin neighborhoods remain the domain of small, aging bungalows – and people without children – for the foreseeable future. In this way, it will reflect the demographic realities of many prosperous, “hip” cities from San Francisco and Boston to Seattle and Portland.

Yet there’s an ironic side to this. Alarmed by the decline of families in the city, the same city council that enacted the McMansion ordinance created a new task force a few months later to determine why central Austin has now so few families with children.

Chris Bradford is a 1992 graduate of the Yale Law School, where he was an Olin Fellow in Law and Economics. He is an attorney at Clark, Thomas and Winters, P.C. in Austin, Texas. Visit Chris’s blog at austincontrarian.com