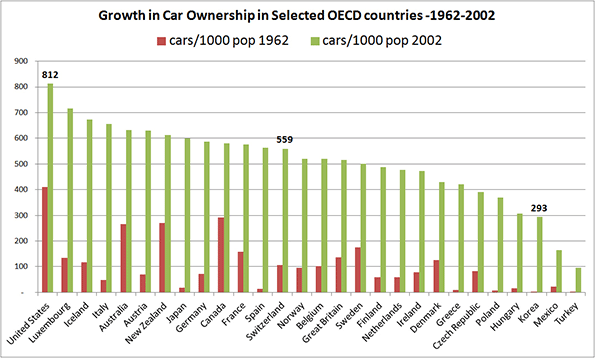

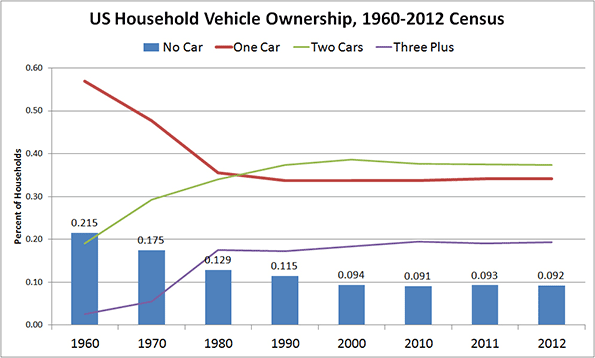

Households are offered a great deal of advice which seems intended to dissuade them from using private, motorised transportation — that is, cars. Information about the negative fallout of car ownership — environmental and otherwise — has often been coloured with ethical overtones. Yet, despite those exhortations and the many well-known and indisputable reasons to cut back, extensive reliance on personal motor transport remains unchanged, if not growing. For example, the rate of car ownership since 1962 has doubled in the US, Canada, Australia and New Zealand; quintupled in Switzerland, Norway and Belgium and tripled in Sweden. This persistent growth alone undermines the claim of a high cost of ownership.

Other trends also back up the notion that cost is not a key issue, and does not belong among the arguments in favour of reducing driving.

Chart 1. Source: Joyce Dargay, Dermot Gately and Martin Sommer: Vehicle Ownership and Income Growth, Worldwide: 1960-2030. Institute for Transport Studies, University of Leeds

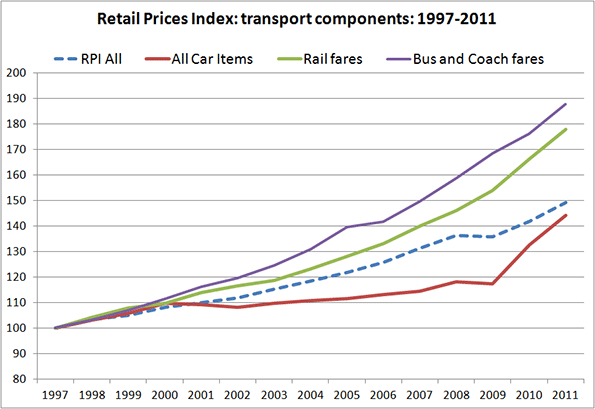

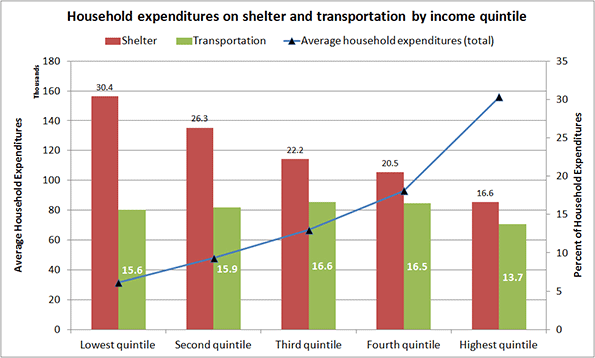

In the US, for example, the costs of buying and operating a car have been continuously dropping. An analogous trend can be seen in the UK (Chart 2), where car costs have risen more slowly than the general retail price index, and slower than rail and bus fares (Note: The UK sustains higher tax levels and gasoline prices than the US.) It stands to reason that lower purchase and operation costs increase the car’s affordability.

Chart 2. Source: UK Department for Transport Statistics 1997-2011 report Table TSGB0123 Retail Prices Index: Transport Components.

Since 1979, incomes in developed countries have been on a rising trend, despite transient periods of economic stagnation. Increased buying power has made numerous commodities — including cars — more accessible.

The obvious affordability of personal motorized transport does not mean that it will or should obliterate other, more affordable transport options: public transit in all its forms, and bicycling or walking.

Public transit’s drawbacks are inflexibility and tardiness. Its reach often excludes employment sites at peripheral locations; as a Brookings Institute report has noted, “…Among very large metro areas, the share of jobs accessible via transit ranges from 37 percent in Washington and New York to 16 percent in Miami.” This limits access to employment for those disadvantaged households that rely entirely on transit for transportation. Though this inflexibility is shared by subway systems, subways generally have a speed advantage over cars in central, congested districts.

The almost no-cost options of walking and cycling are limited by their low maximum speed, and by the effort required. Commuting distances in large cities can often exceed 8 to 12 miles as their diameters range between 15 to 30 miles. Those distances, when undertaken by foot or bike, become untenable because they break the universal half-hour threshold and may require excessive effort. These modes are also ill-suited to trip chains, which involve multiple tasks and destinations on a single trip (e.g. combining work commuting with school drop off/pick-ups, shopping, etc). As with transit, biking and walking has a limited reach of employment destinations. Moreover, a percentage of households may also find it difficult to accommodate all their transportation needs based entirely on these two modes.

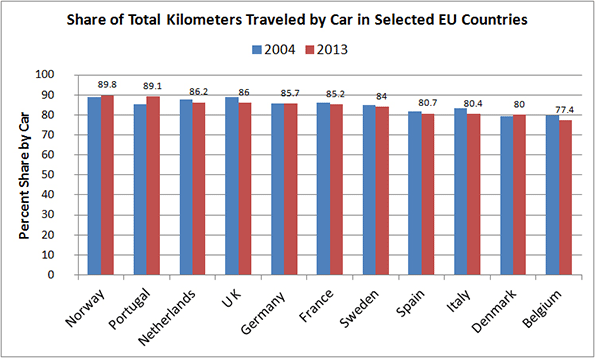

For these and many more reasons, reliance on private vehicles is extensive. That fact is supported by statistics on mode choice among Europeans, who typically have large shares of walking and bicycle trips. The data shows that, when looking at the total kilometers traveled by mode, personal motorised transport takes the lion’s share.

Chart 3. Source: Modal Split of Passenger Transport [tran_hv_psmod] – Eurostat, last update 2015

New ideas in transport that include transit, biking, and new forms of car use are emerging. The innovative solutions that follow are consistent with city-building and environmental objectives. Here are a few possibilities, still in a nascent stage:

Shared car enterprises have sprung up in many urban centers, and offer the convenience of a car without the financial burden of ownership. They reduce total personal driving, and therefore greenhouse gasses (GHGs), as their use is intermittent.

Pay as you drive car insurance and, a recent entry, pay by how you drive insurance. Both provide an incentive to drive less and better. They could reduce car ownership costs, congestion and GHGs.

Electric cars are more economical to operate than conventional vehicles, while reducing pollution and city noise—all positive attributes.

Ride-share services, though controversial, have the potential of reducing the cost of transport by improving its economic efficiency and performance. Both the driver (car owner) and the passenger(s) lower their respective costs, as cars occupancy increases and chained trips become the norm.

Bicycle parking at subway/rail stations increases the potential universe of a subway or rapid-transit bus line (BRT) to four times or more the area of pedestrians within easy reach. This combined personal and communal transport yields excellent affordability.

Bike lane systems on existing streets and paths off the streets increases the perception of safety, which typically increases bike commuting.

Enlarging and enhancing city core sidewalks increases the comfort, safety and pleasure of walking in the city by reducing or removing traffic and, in a similar vein, introducing lanes and passages in the middle of long city blocks reduces walking distances.

Uni-tickets (e.g. London’s Oyster, or New York’s MetroCard) for all public transit services increase the convenience and affordability of public transit and lead to higher ridership.

That’s a short, unsorted excerpt of a longer and growing list of opportunities for transportation planning initiatives. What is not growing — and needs to — is the extent and speed of implementation; a great, worthwhile challenge for planners.

Fanis Grammenos heads Urban Pattern Associates (UPA), a planning consultancy. UPA researches and promotes sustainable planning practices including the implementation of the Fused Grid, a new urban network model. He is a regular columnist for the Canadian Home Builder magazine, and author of Remaking the City Street Grid: A model for urban and suburban development. Reach him at fanis.grammenos at gmail.com.

After twenty-four years at Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation, Tom Kerwin now leads an active volunteer life, including being the Science and Environment Coordinator for the Calgary Association of Lifelong Learners. He holds a Master’s degree in Environmental Studies from York University.

Special thanks to Luis Rodriguez for collaborating in shaping this article.

Flickr photo by Fraser Mummery; Golden Gate Traffic: Auto drivers, pedestrians and a bus on one of the most recognizable structures in the world… the Golden Gate Bridge in San Francisco, California.

Chart 1 Source: Oak Ridge National Laboratory; Transportation Energy Data Book. Table 8.5.

Chart 1 Source: Oak Ridge National Laboratory; Transportation Energy Data Book. Table 8.5. Chart 2 Source: Statistics Canada, Survey of Household Spending. Table 2: Budget Shares Of Major Spending Categories By Income Quintile, 2012.

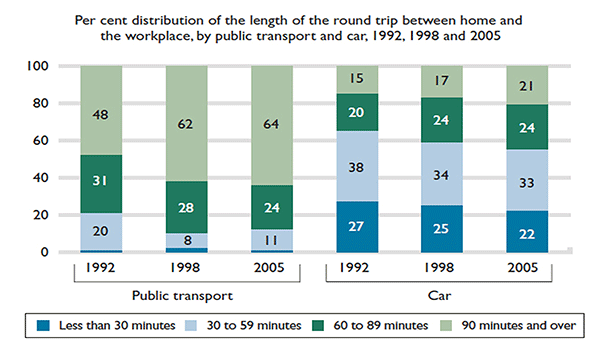

Chart 2 Source: Statistics Canada, Survey of Household Spending. Table 2: Budget Shares Of Major Spending Categories By Income Quintile, 2012. Chart 3 Source: Statistics Canada, General Social Survey, Trip Duration, 1992, 1998, and 2005.

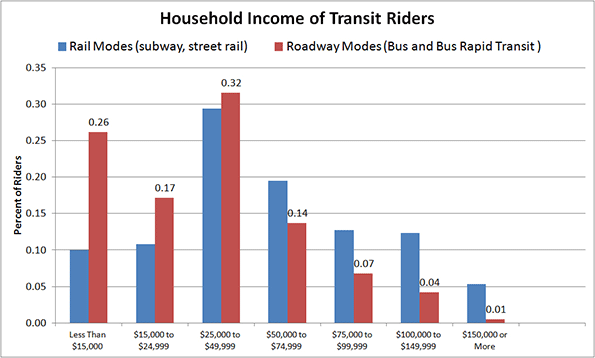

Chart 3 Source: Statistics Canada, General Social Survey, Trip Duration, 1992, 1998, and 2005. Chart 4 Source: American Public Transportation Association, A Profile of Public Transportation Passenger Demographics and Travel Characteristics, 2007.

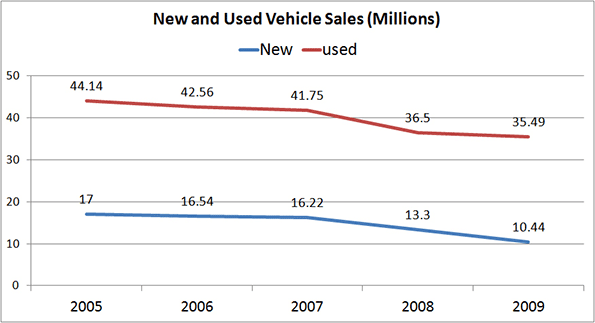

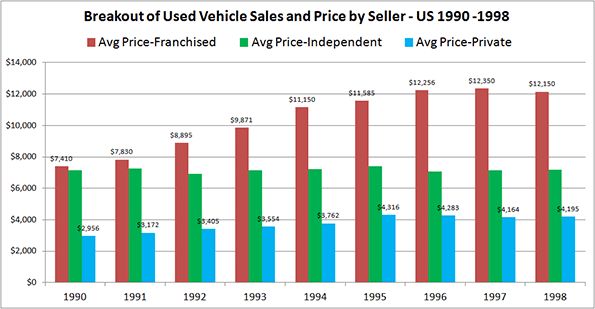

Chart 4 Source: American Public Transportation Association, A Profile of Public Transportation Passenger Demographics and Travel Characteristics, 2007. Chart 5 Source: NIADA’s Used Car Sales Industry Report; Relative Size of Car Markets for New and Used Cars, 2010.

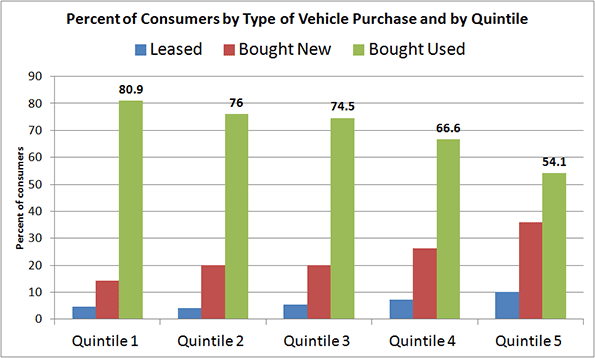

Chart 5 Source: NIADA’s Used Car Sales Industry Report; Relative Size of Car Markets for New and Used Cars, 2010. Chart 6 Source: Laura Paszkiewicz, The Cost and Demographics of Vehicle Acquisition, Consumer Expenditure Survey Anthology, 2003 (61) Division of Consumer Expenditure Surveys, US Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Chart 6 Source: Laura Paszkiewicz, The Cost and Demographics of Vehicle Acquisition, Consumer Expenditure Survey Anthology, 2003 (61) Division of Consumer Expenditure Surveys, US Bureau of Labor Statistics. Chart 7 Source: The Used Vehicle Market in Canada, DesRosiers Automotive Consultants Inc., 2000.

Chart 7 Source: The Used Vehicle Market in Canada, DesRosiers Automotive Consultants Inc., 2000.