The world financial crisis has provoked a stark feeling of decline among many in the West, particularly citizens of what some call the Anglosphere: the United States, Canada, the United Kingdom, Ireland, Australia, and New Zealand. In the United States, for example, roughly 73 percent see the country as on the wrong track, according to an Ipsos MORI poll—a level of dissatisfaction unseen for a generation.

Commentators across the political spectrum have described the Anglosphere as decadent, especially compared with the rising power of China. New York Times columnist Thomas Friedman praises the “reasonably enlightened group of people” who make up China’s one-party autocracy, which, he feels, provides more effective governance than the dysfunctional democracy of Washington, a point echoed in a recent Wall Street Journal op-ed by former Service Employees International Union boss Andy Stern. On the conservative side, author Mark Steyn sees the U.S. and its cultural mother in England as “facing nothing so amiable and genteel as Continental-style ‘decline,’ but something more like sliding off a cliff.” Even Australia, arguably the strongest economy in the Anglosphere, is increasingly troubled, with local declinists decrying the country’s growing dependence on commodity exports to developing nations—above all, to China. “We are to be attendants to an emerging empire: providers of food, energy, resources, commodities and suppliers of services such as education, tourism, gambling/gaming, health (perhaps), and lifestyle property,” frets the Australian’s Bernard Salt.

It’s indisputable that the Anglosphere no longer enjoys the overwhelming global dominance that it once had. What was once a globe-spanning empire is now best understood as a union of language, culture, and shared values. Yet what declinists overlook is that despite its current economic problems, the Anglosphere’s fundamental assets—economic, political, demographic, and cultural—are likely to drive its continued global leadership. The Anglosphere future is brighter than commonly believed.

Start with economics. Like Germany in the 1930s or Japan in the 1970s, China has found that centrally directed economic systems can achieve rapid, short-term economic growth—and China’s has indeed been impressive. But over time, the growth record and economic power achieved by the free-market-oriented English-speaking nations remain peerless. A little-noted fact these days is that the Anglosphere is still far and away the world’s largest economic bloc. Overall, it accounts for more than one-quarter of the world’s GDP—more than $18 trillion. In contrast, what we can refer to as the Sinosphere—China, Hong Kong, Taiwan, and Macau—accounts for only 15.1 percent of global GDP, while India generates 5.4 percent (see Chart 1). The Anglosphere’s per-capita GDP of nearly $45,000 is more than five times that of the Sinosphere and 13 times that of India (see Chart 2). This condition is unlikely to change radically any time soon, since the Anglosphere retains important advantages in virtually every critical economic sector, along with abundant natural resources and a robust food supply.

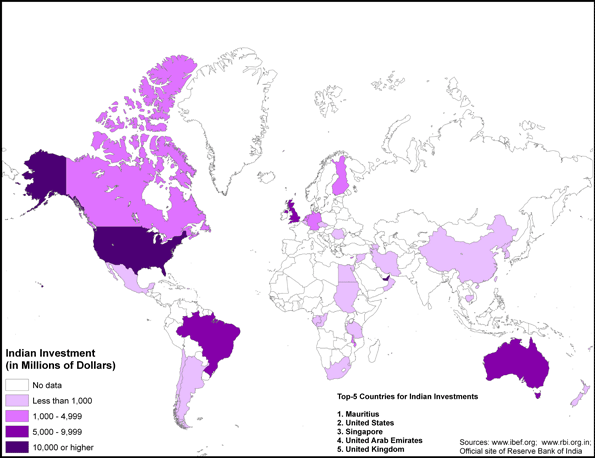

Not surprisingly, Anglosphere countries retain close cultural and economic ties with one another. In making foreign direct investments, the United States shows a strong preference for Anglosphere countries, especially the United Kingdom and Canada (see Chart 3). The same is true for Australia, a nation whose economic future might seem to lie with Asia’s budding economic superpowers. Notwithstanding its worries about becoming a mere attendant to a rising China, Australia tilts its overseas investment heavily toward the United Kingdom, the United States, Canada, and New Zealand.

Anglosphere countries possess overwhelming military superiority to protect their economic interests. While the United States dominates military technology and hardware, Britain ranks fourth in military spending, with both Australia and Canada ranking in the top 15. The U.S. is headquarters to the world’s three largest defense companies: Lockheed, Northrop Grumman, and Boeing. America’s Anglosphere ally Australia has joined informally with Singapore and the Philippines (both are nations where English is spoken widely) to provide a potential regional military counterweight to China.

Anglosphere economic and military leadership is reflected in, and grows out of, the English-speaking world’s remarkable technological leadership. The vast majority of the world’s leading software, biotechnology, and aerospace firms are concentrated in English-speaking countries. Three-fifths of global pharmaceutical-research spending comes from Britain and America; more than 450 of the top 500 software companies in the world are based in the Anglosphere, mainly in the U.S., which hosts nine of the top ten. Out of the ten fastest-growing software firms, six are American and one is British. Internet giants like Apple, Google, Facebook, Microsoft, and Amazon have no foreign equivalents remotely close in size and influence.

English is an ascendant language, the primary global language of business and science and the prevailing tongue in a host of key developing countries, including India, Nigeria, Pakistan, South Africa, Kenya, Malaysia, and Bangladesh. Over 40 percent of Europeans speak English, while only 19 percent are Francophone. When German, Swedish, and Swiss businesspeople venture overseas, they speak not their home language but English.

Long-run trends in the developing world also point to the expansion of the English language. French schools have been closing even in former French colonies, such as Algeria, Rwanda, and Vietnam, where students have resisted learning the old colonial tongue. English is becoming widely adopted in America’s biggest competitor, China, and it dominates the Gulf economy, where it serves as the language of business in hubs such as Dubai. The Queen’s tongue is, of course, broadly spoken in that other emerging global economic superpower, India, where it has become a vehicle for members of the middle and upper classes to communicate across regional boundaries. In Malaysia, too, English is the language of business, technology, and politics.

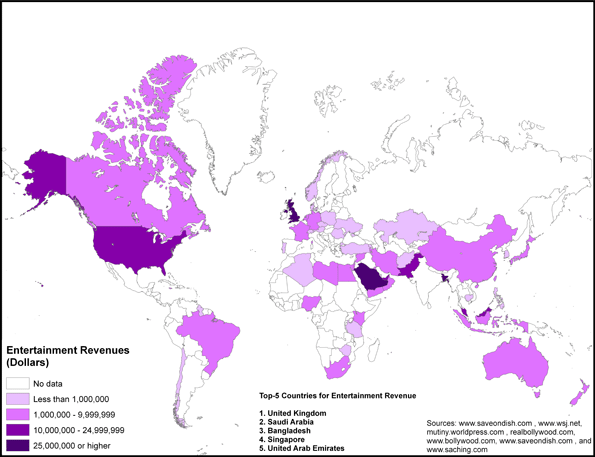

With linguistic ascendancy comes cultural power, and the Anglosphere’s remains uncontested. In total global sales of media, movies, television, and music, it has no major competitor. Its exports of movies and TV programs dwarf those of established European powers like France and Germany and upstarts such as China, Brazil, and India (see Chart 5). Exports from Hollywood and the cultural capitals of other Anglosphere countries are growing enormously in developing countries: Hollywood box-office revenues grew 25 percent in Latin America and 21 percent in the Asia-Pacific region (with China accounting for 40 percent of that region’s box office). The hit movie Avatar made over $2 billion outside North America; in Russia, Hollywood films earn twice as much as their domestic counterparts. Anglophone preeminence extends to pop music, with Americans Eminem, Lady Gaga, and Taylor Swift, along with the U.K.’s Susan Boyle, ruling global charts. Japanese, Korean, and Chinese pop artists do have large followings in Asia, but the biggest global stars continue to originate in the Anglosphere. This is true of fashion trends, too: Los Angeles, New York, and London dominate fashion for everything from sportswear to lingerie in the increasingly global “mall world.”

Much has been made of the aging of the West, but the English-speaking countries are not graying as rapidly as their historical European rivals are—notably, Germany and Italy—or as Russia and many East Asian countries are. Between 1980 and 2010, the U.S., Canada, and Australia saw big population surges: the U.S.’s expanded by 75 million, to more than 300 million; Canada’s nearly doubled, from 18 million to 34 million; and Australia’s increased from 13 million to 22 million. By contrast, in some European countries, such as Germany, population has remained stagnant, while Russia and Japan have watched their populations begin to shrink.

The U.S. now has 20 people aged 65 or older for every 100 of working age—only a slight change from 1985, when there were 18 for every 100. By 2030, the U.S. will have 33 seniors per 100 working Americans. But consider the numbers elsewhere. In the world’s fourth-largest economy, Germany already has 33 elderly people for every 100 of working age—up from only 21 in 1985. By 2030, this figure will rise to 48, meaning that there will be barely two working Germans per retiree. The numbers are even worse in Japan, which currently has 35 seniors per 100 working-age people, a dramatic change from 1985, when the country had just 15. By 2030, the ratio is expected to rise to 53 per 100.

Meanwhile, the nation that so many point to as the twenty-first-century superpower—China—now has a fertility rate of 1.6, even lower than that of Western Europe. Over the next two decades, its ratio of workers to retirees is projected to rise from 11 to 23. Other countries, such as Brazil and Iran, face similar scenarios. These countries, without social safety nets of the kinds developed in Europe or Japan, may get old before they can get rich.

These figures will have an impact on the growth of the global workforce. Between 2000 and 2050, for example, the U.S. workforce is projected to grow by 37 percent, while China’s shrinks by 10 percent, the EU’s decreases by 21 percent, and, most strikingly, Japan’s falls by as much as 40 percent.

In this respect, immigration presents the most important long-term advantage for the Anglosphere, which has excelled at incorporating citizens from other cultures. A remarkable 14 million people immigrated to Anglosphere countries over the last decade. The United States, in particular, remains a powerful magnet: in 2005, it swore in more new citizens—the vast majority from outside the Anglosphere—than the next nine countries put together. The U.K. last year also experienced the strongest immigration in its history.

In sum, post-financial-crisis reports of the Anglosphere’s imminent irrelevance have been exaggerated—wildly.

This piece originally appeared in The City Journal.

Joel Kotkin is executive editor of NewGeography.com and is a distinguished presidential fellow in urban futures at Chapman University, and contributing editor to the City Journal in New York. He is author of The City: A Global History. His newest book is The Next Hundred Million: America in 2050, released in February, 2010.

Shashi Parulekar is the director of global sales and marketing and chief technology officer for Zemarc Corporation.

Graphs by Robert Pizzo