Democratic “blue” state attitudes may dominate the national media, but they can’t yet tell people where to live. Despite all the hype about a massive “back to the city” movement and the supposed superiority of ultra-expensive liberal regions, people are increasingly moving to red states and regions, as well as to suburbs and exurbs.

This is the basic takeaway from the most recent IRS data and Census Bureau estimates, which have been widely ignored in the established media. Essentially, Americans are rejecting what Walter Russell Mead has labelled “the blue model,” and relocating to cities, states and regions that are less dense, less heavily taxed, and less regulated.

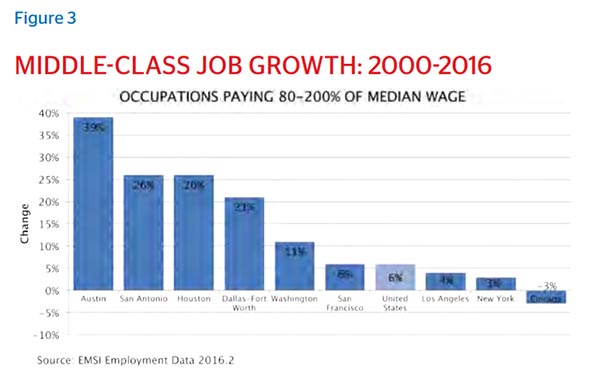

This suggests not an intrinsic political calculation so much as a series of very personal decisions by individuals and families. People move for varied reasons — cheaper homes, lower taxes, employment opportunities, better schools, more value to the paycheck — but the upshot is that they are settling in states that tend to be red or, at least, purple in political coloration.

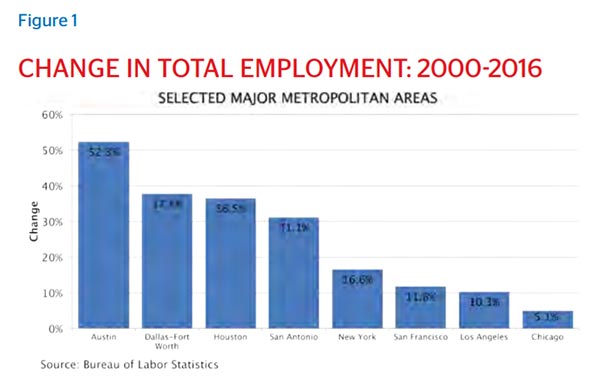

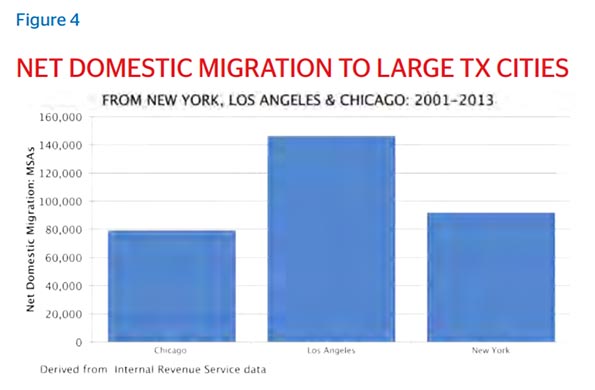

In 2016 alone, states that supported Donald Trump gained 400,000 domestic migrants from states that supported Hillary Clinton. This came on top of an existing advantage in net domestic red state migration of 1.45 million people from 2010 through 2015. Contrary to popular perception, these blue state emigres aren’t all fleeing economically challenged places such as upstate New York or inland California. Mostly, they have left the biggest cities, which are the electoral base of the Democratic Party. Metropolitan New York has led the way in out-migration, followed by Los Angeles and Chicago. Since 2000, these metropolitan areas have lost a net 5.5 million domestic migrants to other parts of the country.

Even economic boom conditions have failed to reverse this trend. Overall, many big blue core cities now have overall population growth rates well below the somewhat tepid national average of 0.7 percent. So, who’s growing? Last year, all 10 of the top gainers in domestic migration were Sunbelt metropolitan areas: Austin, Tampa-St. Petersburg, Raleigh, Jacksonville, Las Vegas, Charlotte, Orlando, Nashville, Phoenix and San Antonio.

Perhaps most surprising, given the almost universal dismissal of their prospects, has been a shift to smaller cities, a more Trump-oriented part of the urban archipelago. Domestic migration has accelerated to cities between 500,000 and 1 million population, while declining in those above 1 million.

The Suburban Resurgence

More important still has been the revival in the suburbs, particularly in Sunbelt metropolitan areas. The most recent estimates suggest that last year was the best for suburban areas since the Great Recession. In 2012, the suburbs of the major metropolitan areas (over 1 million) attracted barely 150,000 more people than core counties, an edge that grew to 556,000 last year. Between 2010 and 2015, suburban counties of major metropolitan areas added 825,000 net domestic migrants, while the urban core counties lost nearly 600,000.

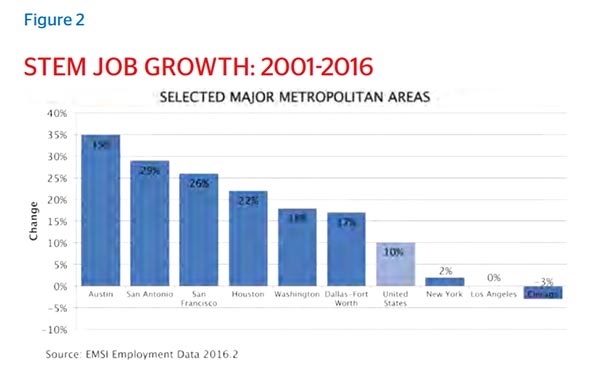

Critically, since 2010 more than 80 percent of all new jobs in our 53 leading metropolitan regions have been created in suburban locations. Many of the leading tech areas of the country –from Silicon Valley and Raleigh-Durham to tech centers surrounding the big Texas cities — are primarily suburban. The economic future, contrary to the common media memes, will be primarily occurring in the periphery of the hip urban cores.

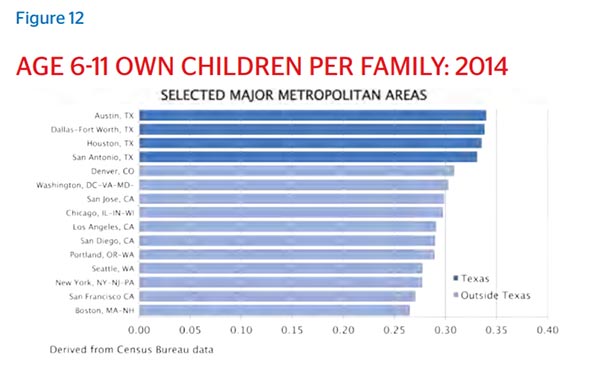

This trend may accelerate as millennials begin to enter their 30s and look for safe, affordable places to live. We already see this in the behavior of their predecessors, the X generation. Using census data of those 35-49 as our measurement, since 2000 the percentage of Gen-Xers living in the urban core has dropped by one percentage point, while the percentage living new suburbs and exurbs has grown by six percentage points. The latest estimates indicate over 80 percent of Xers in the 53 largest metropolitan areas lived in suburban areas.

Gen-Xer shares grew most dramatically in the affordable Sunbelt, like almost completely suburban Raleigh, which saw a 50 percent growth in the share of Xers relative to the national rate. Rapid growth also took place in Las Vegas, Charlotte, Phoenix, Orlando and Salt Lake City as well as the big four Texas cities: Austin, Houston, Dallas-Fort Worth, and San Antonio.

In contrast the Gen-X population share has remained stagnant in the San Francisco and San Jose areas, while the Los Angeles, New York, Boston, Chicago and Philadelphia areas have all seen declines in their Xer shares both since 2000 and since 2010. This could be a harbinger of millennial behavior. Like the Xers, millennials are beginning to move into the suburbs, contradicting all predictions to the contrary. Since 2010, the biggest gains in millennial share have been in heavily suburban Orlando, Austin and San Antonio.

Generally speaking, notes economist Jed Kolko, the peak years for living in higher density multi-family neighborhoods take place between ages 18 and 30. Kolko calculates that while almost a quarter of these under-30 urban dwellers live in these higher density neighborhoods, by age 40 this drops well below 20 percent, and stays there until people are into their 70s. Given that the 30-something population is destined to grow far faster than 20-somethings in the coming decades, the move to suburbia, with its detached housing — particularly in regions with lower home prices — is expected to continue for the foreseeable future.

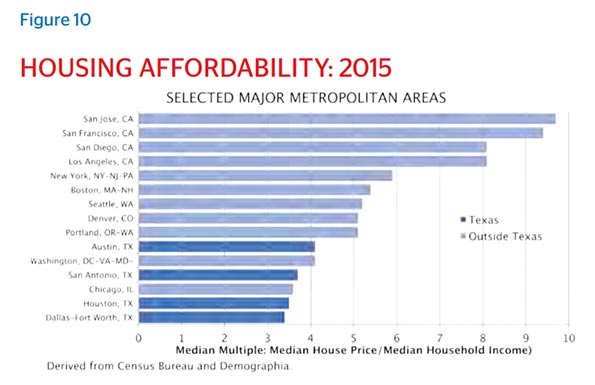

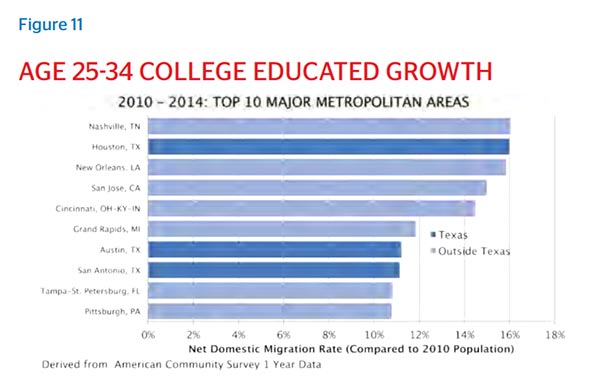

This shift is likely to be driven in large part by unsustainable housing costs. In the San Francisco Bay Area, techies are increasingly looking for jobs outside the region, and some companies are offering cash bonuses for those willing to leave. A recent poll indicated that 46 percent of millennials want to leave the Bay Area. Meanwhile, these “best and brightest” have been gravitating to lower cost areas such as Austin, Orlando, Houston, Nashville, and Charlotte.

The basics that drive people to the suburbs remain: cheaper real estate, a preponderance of single family housing, better schools, a poverty rate roughly half that of core municipalities as well as far lower incidence of violent crime than in urban cores. This trend will be accelerated, as a recent policy analysis released by the consulting firm Bain shows, by services such as Uber or Lyft, the appeal of working at home as well as the development of automated vehicles.

Political Implications

Ultimately, the key political battlegrounds for the future will not be in blue cities but in purple suburbs, particularly in the booming periphery of major cities in red states. No matter how loud and pervasive the voices emanating from the urban core, or for that matter, ungentrified countryside, Trump won the election by taking by a significant five percentage point suburban margin nationally, improving on Romney’s two-point edge, and by more outside the coastal regions.

This contradicts the confident assertions by the New York Times and other establishment voices that Trump would get his clock cleaned in suburbia, particularly among college-educated voters in upscale communities. Suburban voters made the difference in the crucial Midwestern states of Michigan, Wisconsin and Pennsylvania, and Trump came close to winning in supposedly deep blue Minnesota.

In Michigan, Trump lost Wayne County (including Detroit) by more than 2-1, but captured four of the five surrounding suburban counties by margins that greatly exceeded that of Michigan native Romney. The pattern was similar in Pennsylvania where Clinton won in the Philadelphia metropolitan area – and Pittsburgh’s urban Allegheny County, while Trump was flipping the state with majorities in nearly every other county. Much the same can be said about Wisconsin and Ohio, states critical as well to the Trump win and the GOP future.

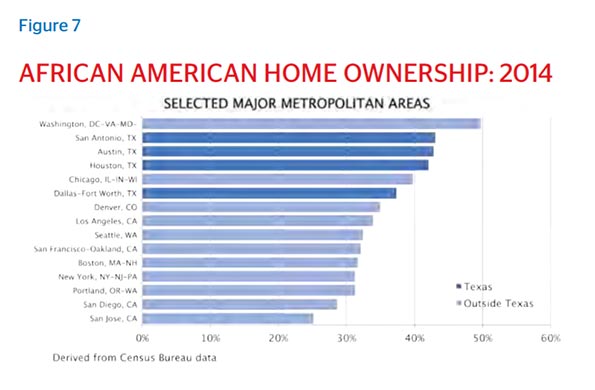

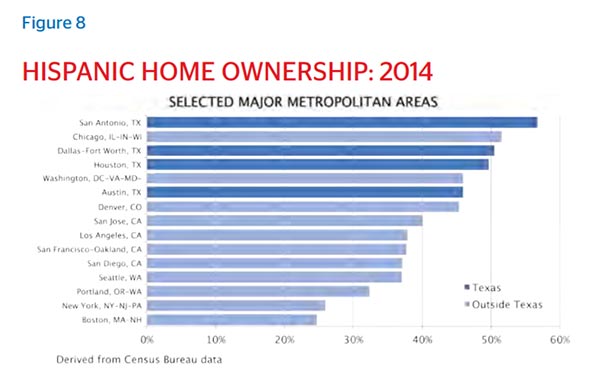

This pattern is not set in stone. Trump, as the New York Times recently enthused, does suffer from continuing problems with educated suburban voters. Perhaps even more threatening to the GOP is that minorities now account for more than 40 percent of all suburban and exurban residents, growing far faster in the periphery than non-Hispanic whites. Trump lost traditionally right-leaning but rapidly diversifying places such as Orange County, Calif., and Fort Bend County outside of Houston.

Yet, winning over suburbia in the long run may not be easy for the Democrats. As millennials and Xers, as well as minorities, begin to own property and earn more money, their attitudes on taxes tend to shift to a more conservative perspective, notes a recent Reason poll. Similarly many first-generation Asian immigrants tend to be far more conservative than second- or third-generation Chinese- or Korean-Americans, many of whom have been through college indoctrination and are comfortably ensconced in the generally Democratic-leaning high-end professional class.

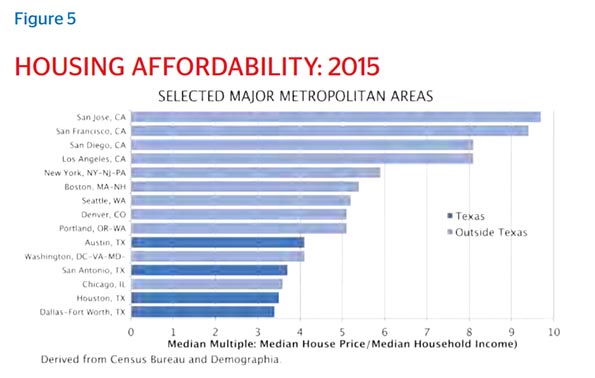

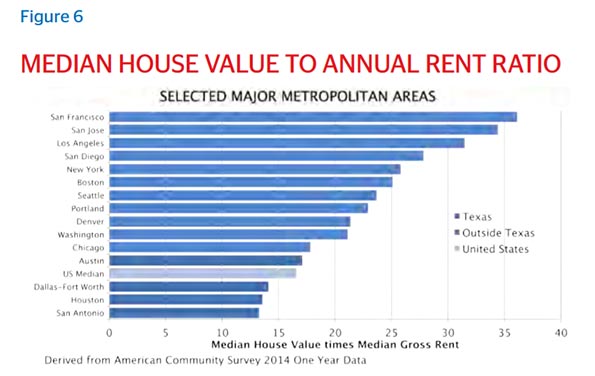

Perhaps the biggest problem for the left lies in their embrace of policies that reject suburban lifestyles and, as we see in California, make housing hard to build and all but unaffordable. Most millennials and Xers, not to mention minorities, cannot afford to live in places like brownstone Brooklyn or San Francisco. In adopting policies to curb “sprawl,” blue state politicians are assaulting the suburban lifestyles clearly preferred by the clear majority. This leftist urban policy does not constitute an ideal strategy to appeal to those, including minorities, who want nothing more than to live comfortable lives on the periphery.

Right now, the demographic trends do not clearly favor either party. The new generation now forming families — and heading towards the red states — may not be as conservative as boomers but their politics are less lock-step progressive than many believe, even on gender-related issues. They may want health-care reform, good schools, and cleaner environments. But they also want jobs, would like to hold onto more of their paychecks, and cherish the same suburban amenities they enjoyed as children.

Ultimately, it’s a matter of which politicians can delineate the best path toward greater opportunity and homeownership for middle-class families. The political party that addresses these aspirations is likely to be the one that wins the race in the long run.

This piece first appeared on Real Clear Politics.

Joel Kotkin is executive editor of NewGeography.com. He is the Roger Hobbs Distinguished Fellow in Urban Studies at Chapman University and executive director of the Houston-based Center for Opportunity Urbanism. His newest book, The Human City: Urbanism for the rest of us, was published in April by Agate. He is also author of The New Class Conflict, The City: A Global History, and The Next Hundred Million: America in 2050. He lives in Orange County, CA.

Wendell Cox is principal of Demographia, an international public policy and demographics firm. He is a Senior Fellow of the Center for Opportunity Urbanism (US), Senior Fellow for Housing Affordability and Municipal Policy for the Frontier Centre for Public Policy (Canada), and a member of the Board of Advisors of the Center for Demographics and Policy at Chapman University (California). He is co-author of the “Demographia International Housing Affordability Survey” and author of “Demographia World Urban Areas” and “War on the Dream: How Anti-Sprawl Policy Threatens the Quality of Life.” He was appointed to three terms on the Los Angeles County Transportation Commission, where he served with the leading city and county leadership as the only non-elected member. He served as a visiting professor at the Conservatoire National des Arts et Metiers, a national university in Paris.

Photo: Mark Turner (Own work) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons