A city at its best, wrote the philosopher René Descartes, provides “an inventory of the possible.” The city Descartes had in mind was 17th-century Amsterdam, which for him epitomized those cities where people go to change their circumstances and improve their lives. But such aspirational cities have existed throughout American history as well, starting with Boston in the 17th century, Philadelphia in the 18th, New York in the 19th, Chicago in the early 20th, Detroit in the 1920s and 1930s, followed by midcentury Los Angeles, and San Jose in the 1980s.

Yes, the great rule of aspirational cities is that they change over time, becoming sometimes less entrepreneurial, more expensive, and demographically stagnant. In the meantime, other cities, often once obscure, suddenly become the new magnets of opportunity.

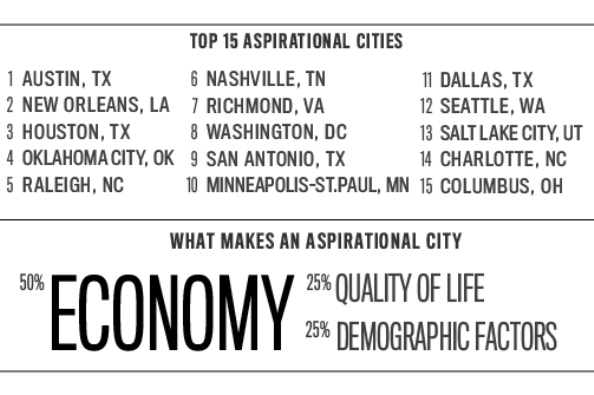

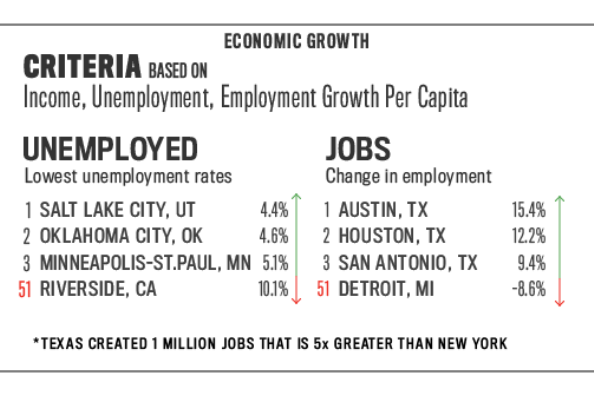

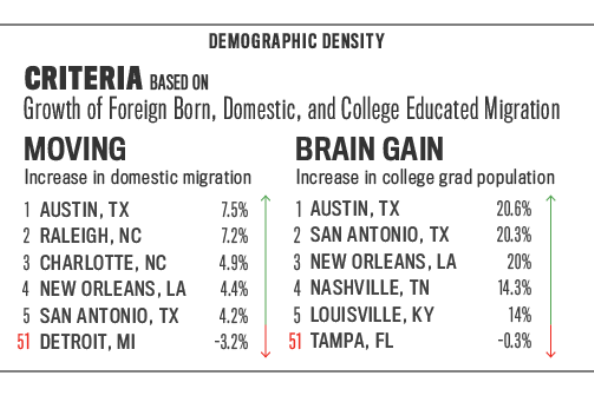

To determine America’s current aspirational hotspots, we focused in large part on economic indicators, such as employment growth, per capita income, and unemployment. But we also took into account demographic factors, such as the growth of domestic migration and the movement of college-educated people and the foreign born.

Finally, we considered quality-of-life factors such as traffic congestion, housing affordability, and crowding—which are keenly relevant to young families hunting for the places with the best “inventory of the possible.” In a sense, we believe aspirational cities reflect a kind of urban arbitrage, where people look for those places that provide not just economic and cultural opportunity but a cost structure that allows them to enjoy their success to the fullest extent.

Our top two cities reflect the importance of this arbitrage opportunity. Both No. 1, Austin, Texas, and No. 2, New Orleans, are places where people can enjoy the cultural amenities and attitudes of “progressive” blue states but in a distinctly red-state environment of low costs, less regulation, and lower taxes. These places have lured companies and people from more expensive regions, notably California and the Northeast, by being not only culturally rich but also amenable to building a career, buying a home and, ultimately, raising a family in relative comfort.

Like the Texas state capital and the legendary Crescent City, most of our top cities are located in the American South and lower Midwest, and they attract businesses and people not only from other sections of the country but also increasingly from abroad as well. These include No. 3, Houston, and the smaller but burgeoning oil town of No. 4, Oklahoma City. These are followed by three fast-growing, low-cost Southern cities: No. 5, Raleigh-Cary, North Carolina; No. 6, Nashville; and No. 7, Richmond, Virginia.

Not all our top aspirational cities are in Dixie. If there’s enough growth and opportunity, solidly blue-state regions can perform well enough to stay near the top of these rankings. Such cities include No. 8, Washington, D.C., and No. 10, Minneapolis–St. Paul, as well as No. 12, Seattle; No. 16, Denver; and even No. 22, Boston. In these cities, high-tech and professional-service growth has created enough wealth to offset higher costs while offering the next generation the chance to live in a culturally vibrant place where affording a home and raising a family are still possible.

Perhaps more surprising is the high aspirational ranking of some old Rust Belt and Great Lakes cities. The middle part of the country has been losing people and jobs for half a century, but more recently several urban areas within or bordering the Midwest have established enough of an aspirational culture to reverse the pattern of out-migration and begin luring people from the coasts. These include such diverse places as No. 15, Columbus, Ohio; No. 17 Louisville, Kentucky; No. 21 Pittsburgh; and No. 23, Indianapolis.

Of course, not everyone will find a perfect match in one of these cities. For those with extraordinary technical skills, for example, it still may make sense to move to the hotbed of the San Francisco Bay Area—notably No. 24, San Francisco, and No. 27, San Jose—where economic opportunity partially offsets extraordinarily high costs, at least for a certain portion of the population.

This applies as well even to cities toward the bottom of the list, including No. 46, New York, and, in last place, No. 51, Los Angeles. If you want to break into businesses such as finance, media, and entertainment, you have little choice but to concentrate on New York or Southern California. These areas may also prove more attractive to people who have inherited money (critical to affording houses or paying high rents), as well as those whose business is closely tied to these great cities’ ethnic economies.

People must also make tradeoffs when they decide where to locate. Some value a big house and yard, while others cannot abide a city without a decent opera or good Thai food. And those obsessed with, say, their children’s educations will clearly find a broader variety of schools and cultural institutions in San Francisco or New York than in Oklahoma City.

But for those who lack these specific demands, and for those whose priority is achieving a middle- or upper-middle-class quality of life, the less expensive, often smaller, and less congested cities seem to have the greatest appeal. This may offend the sensibilities of retro-urbanists, who tend to cluster in the great legacy cities, along with our tribes of cultural tastemakers, but the hard reality shows that, for the most part, people move to places that offer not merely the best lattes or artisanal pizzas but the great opportunity for advancement.

The Geography of Growth

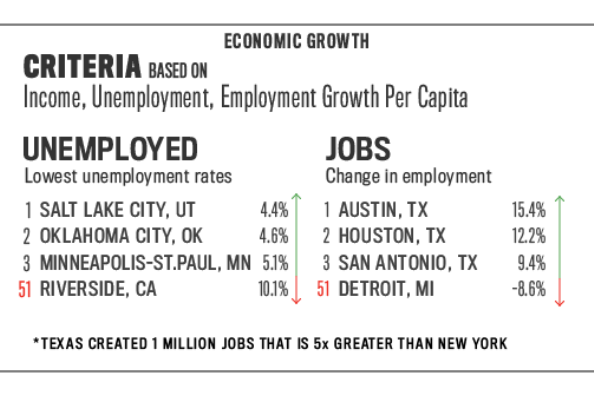

We give economic growth roughly half of the weight in these rankings. This consists of three factors: employment growth, unemployment, and per capita income. This is where some of the coastal cities still do well, notably San Jose, whose recent job growth places it first, as well as No. 4, Washington, and No. 7, Seattle. The local economies in these areas have all been driven by the rapid expansion of high-tech and professional services, which explains their particularly high per capita GDP numbers.

Yet most of the big winners in the economic-aspiration sweepstakes are concentrated elsewhere, notably in Texas. Since the recession, the Lone Star State has created 1 million new jobs, five times as many as New York state. In contrast, Florida and California have lost a half million positions. Not surprising, Texas accounts for four of the top 11 regions for economic opportunity (No. 2, Austin; No. 3, Houston; No. 9, San Antonio; and No. 11, Dallas).

No big economic region outperforms Houston, a metropolitan area of more than 5 million people that boasts arguably the strongest big-city economy in the nation. Not only the global hub of the energy industry, it also boasts the nation’s largest medical center and has dethroned New York City as the nation’s leading export center. Other strong performers include No. 7, Salt Lake City; No. 8, Oklahoma City; and No. 11, New Orleans, all of which have enjoyed strong job growth over the past five years.

What Do You Get for the Money?

Strong economic growth—particularly high per capita incomes—represents half of our ranking, but this is balanced by considerations such as cost of living, housing, and traffic congestion. “Everyday life,” observed the great French historian Fernand Braudel, “consists of the little things one hardly notices in time and space.” This reality is particularly critical for young and prospective families, for whom a higher salary or glamorous environment may mean less than the prospect of owning a decent home, particularly without the necessity of a long, dispiriting commute.

These factors, we believe, will become more paramount as members of the large millennial or “echo boom” generation enter their late 20s, 30s, and even 40s over the next decade. This demographic—projected by the census to expand by roughly 8 million by 2025—is likely to prove intensely interested in owning their own homes. Indeed, research by generational analysts Morley Winograd and Mike Hais demonstrates that not only do millennials aspire to homeownership, but among the oldest cohorts of this group, now just entering their 30s, interest in buying a house actually surpasses that of their boomer parents.

This difference in the affordability of housing relative to incomes plays a major role in boosting the rankings of some strong aspirational areas, notably Raleigh; Richmond; Charlotte, North Carolina; Kansas City; and Indianapolis. Along with traffic congestion, it tends to bring down the rankings of most California metropolitan areas, including San Francisco, San Jose, Los Angeles, and San Diego, as well as such hipster hotspots as New York and Miami. We also include “doubling up,” where more than one family lives in a household, as a surrogate for poverty (since metropolitan poverty rates are not adjusted for the cost of living).

Demographic Destiny

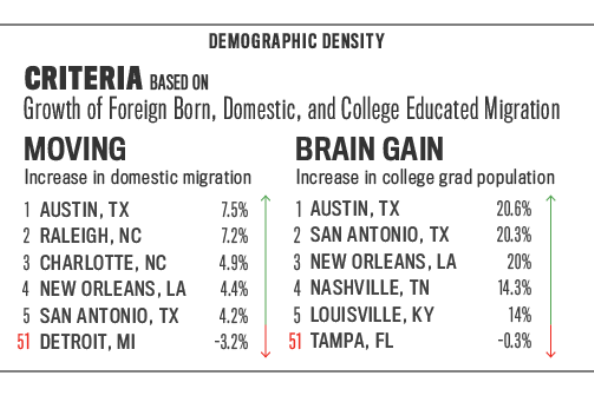

The last component of our rankings, accounting for roughly a quarter, lies in demographic trends. Like playing defense in basketball, the most important thing here is to watch the feet. The question is movement: where are people going, and where are they not? This tells us much about future trends and how people, as opposed to the media, actually view the best places for them to settle.

Our methodology concentrates on three metrics: domestic migration, growth of foreign-born population; and growth in the number of college-educated people. These groups reflect what may be thought of as “the canaries in the coal mine”—indicators of where people seeking a better life are choosing to settle. This factor seems to jibe with our overall rankings more than any other component.

The biggest beneficiaries tend, not surprisingly, to be places that are economically vibrant but not prohibitively expensive, such as Austin, Houston, San Antonio, Dallas, Raleigh, Nashville, Richmond, and Charlotte. Over the past decade these areas have enjoyed by far the fastest growth not only in migration, but in college-educated people and perhaps most surprisingly in number of foreign-born people. Today immigrants are flocking to such unlikely places as Nashville, Richmond, Louisville, and Charlotte. As for the college-educated, they, too, are also migrating to these same aspirational cities, as well as to new hipster hotspots such as New Orleans and Nashville. The increase in B.A.-degree holders in these cities averages in the double digits or higher over the past decade, in some cases more than twice the growth in such traditional “brain gain” cities as Seattle, San Jose, San Francisco, New York, and Boston.

The Urban Future

As the younger generation, as well as newly arrived immigrants, begins to look for places to settle, raise families, and start businesses, they will flock increasingly to these affordable and demographically, economically dynamic regions. Yet it is likely that other factors—global economics, shifts in immigration, and technological changes—could influence the aspirational landscape in the years to come.

In thinking about the future, then, it is important to recall that not long ago some of the cities near the top of today’s aspirational list were facing seemingly irreversible economic decline, demographic stagnation, and even loss and deterioration of basic infrastructure. You only have to recall the dismal ’70s in Seattle, where post-Vietnam budget cuts inspired some to ask that “whoever is last to leave turn out the lights,” or Houston and Dallas–Fort Worth after the oil bust in the ’80s, when those cities were widely known for their “see through” office buildings and abandoned housing complexes.

It’s always possible that unpredictable and major shifts could topple today’s aspirational cities from the top of the list. However, given current conditions and the most likely accrual of current trends, we can expect that most of the cities at the top of the aspirational rankings will remain there for some time to come.

Joel Kotkin is executive editor of NewGeography.com and Distinguished Presidential Fellow in Urban Futures at Chapman University, and a member of the editorial board of the Orange County Register. He is author of The City: A Global History and The Next Hundred Million: America in 2050. His most recent study, The Rise of Postfamilialism, has been widely discussed and distributed internationally. He lives in Los Angeles, CA.

Wendell Cox is a Visiting Professor, Conservatoire National des Arts et Metiers, Paris and the author of “War on the Dream: How Anti-Sprawl Policy Threatens the Quality of Life.

This piece originally appeared at the Daily Beast.

Creative Commons photo “Austin Skyline” by Flickr user StuSeeger