America has always been a nation of tinkerers. Our Founding Fathers, notes author Alec Foege, were innovators in areas ranging from agriculture (George Washington, Thomas Jefferson) and electricity (Benjamin Franklin) to the swivel chair (Jefferson).

Engineering advances drove America’s quest for industrial supremacy in the 19th century, many of them borrowed (sometimes illegally) from the then very resourceful British Isles. By the early 19th century, the U.S. was producing its own major inventions, including the steamboat and cotton gin. By the end of that century, the U.S. was clearly on the way to industrial preeminence. The growth of engineering schools — MIT, the Case Institute, Stevens Institute of Technology, as well as departments at the great land grant universities — generated a steady supply of engineers. For much of the last 70 years, America, has been the world’s leading center of engineering excellence, dominating markets from steel and cars to energy and aerospace.

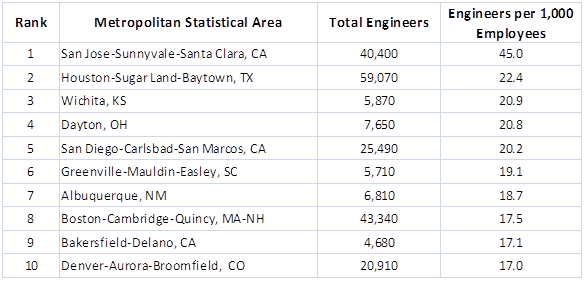

Today, as well, where engineers concentrate, we can expect the greatest capacity for innovation. According to research from Houston Partnership economist Patrick Jankowski, there is a wide range of concentrations of engineering talent among the country’s 85 largest metropolitan areas. For the most part, regions with higher concentrations of engineers tend to do better, and seize the leadership of key industries.

Nowhere is this more true than in America’s top engineering hub, San Jose/Silicon Valley. The Valley’s ratio of 45 engineers per 1,000 employees is twice as high as any other big metro area. This deep reservoir of talent remains the Valley’s key asset, and has made it by most measurements the nation’s most affluent metro area.

This preeminence dates to the Valley’s early history, particularly in research sponsored by the Defense Department and NASA. This large high-tech workforce was then backed by venture capitalists, many of them also engineers by training, to form by far the most dominant high-tech region in the world. The presence of Stanford, now rated the nation’s second leading engineering school by U.S. News & World Report after MIT, Berkeley, ranked third and Santa Clara, at No. 14, gives the area an unmatched capacity to produce technologists.

More surprising, perhaps, is the second city on our list: Houston. The world energy capital is home to 59,000 engineers — second most in the U.S. after the much larger Los Angeles metro area — and has a concentration of 22.4 engineers per 1,000 employees. Although it does not match the Bay Area in elite engineering schools, Houston is home to Rice University and the University of Houston, both highly regarded, and, perhaps equally important, a strong sub-structure of trade and technical schools that feed into the engineering pool.

Key here is the energy industry, which is far more technology-dependent than many might believe. Houston is arguably now the country’s most important emerging city, with the largest job growth of any major metro area. Not only can engineers make money there, unlike in Silicon Valley, they can also afford to buy a house.

More surprising still is the metro area with the third-highest concentration of engineers: Wichita, Kan., with 21 engineers per thousand employees. In this case, the driver is manufacturing, particularly aerospace. But recent cuts by Boeing threaten the future of the self-proclaimed “air capital of the world.” As a result, Wichita has not done nearly as well economically of late as San Jose or Houston, but its reservoir of engineering talent suggests considerable potential if they stick around.

These top three engineering cities tell us much about the source of American innovation, and the remarkable diversity that makes this country an engineering powerhouse. It involves three essential industries — information technology, energy and manufacturing. Each has a distinct geographic makeup that reflects differing kinds of engineering talent.

The High-Tech Centers

No place comes close to Silicon Valley in terms of concentrations of engineers, but several other traditional tech centers make the top 10, led by San Diego in fifth place, a major center for biotech. Boston, home to No. 1 engineering school MIT, ranks eighth, and Denver, which boasts both a thriving tech and energy sector, is 10th. Other tech regions that rank in the top 20 include Seattle (13th), San Francisco (18th) and Austin (19th). None of these areas can claim even half of Silicon Valley’s per capita engineering base, but have thrived during the current high-tech boom.

The Energy Cities

When thinking of energy, we might think of wildcats covered with crude (like James Dean in Giant), but this is becoming an industry very dependent on highly trained geophysicists, petroleum engineers, chemical engineers and other specialists. This explains the ninth-place ranking for Bakersfield, “the oil capital of California,” a city better known for country music and cruising than technology. Over 15,000 people work in this generally high-wage industry in the onetime Okie capital. Energy jobs are also big in No. 14 Baton Rouge, La., home to Louisiana State University, which sends many of its engineering graduates into the Gulf of Mexico energy industry.

Manufacturing Hubs.

Detroit’s bankruptcy has shed a bad light on rustbelt centers, but in reality the industrial Midwest has been on something of a roll in recent years, with many states, from Wisconsin and Ohio to Iowa, boasting lower unemployment than the national average. One key element has been the increasingly innovative nature of U.S. manufacturing, notably in the auto industry. Little-recognized Dayton, which ranks fourth, has attracted major investment for advanced manufacturing in autos and aerospace.

Other manufacturing cities high on our list include No. 6 Greenville-Easley, S.C., home to many European auto-related firms. And despite the city bankruptcy we should not ignore No. 12 Detroit, where most of the metro area’s 30,000 engineers live in the economically healthy suburban regions.

These numbers, of course, focus on concentration as opposed to absolute numbers of engineers. In terms of raw numbers, by far the largest player is Los Angeles, with some 70,000 engineers. Yet it ranks only 33rd by concentration, a far cry from the region’s aerospace-oriented heyday. But L.A.’s legacy still makes an ideal setting for some tech ventures, notably Elon Musk’s SpaceX.

In terms of total engineers, L.A. is followed by Houston, with 59,000, Washington-Arlington-Alexandria with 49,000 (11th in terms of concentration), Boston with 43,000 and then San Jose and Dallas (29th), each with 40,000 or so engineers. Each has a critical mass that allows them to tackle big engineering projects, while also staffing potential spin-offs and start-ups. Some of these areas, notably the Valley, know how to make more money with their workforce than others.

The Have-not Regions

One surprisingly weak area is greater New York, which ranks 78th, with a miniscule 6.1 engineers per 1,000 workers, and some 20,000 fewer engineers than Los Angeles. The New York media and the city’s chattering classes may like to talk up the Big Apple as a high-tech center, but the relative lack of engineering talent should spark a tad of skepticism over whether the nation’s largest urban area is really up to the task of competing against engineer-rich places like Boston, San Diego, Seattle, Denver or Austin, much less stand up to Silicon Valley, with seven times the concentration of engineers.

The rest of the bottom of the list is depressingly familiar, in terms of economic also-rans. El Paso, Texas, ranks last among the 85 largest metropolitan areas, followed by Las Vegas, Scranton-Wilkes Barre, Pa., and Fresno. These cities are going to have a very tough time competing for high-tech jobs in the immediate future. To make something, whether digital or tangible, the first step lies in gathering in the talent that can make things happen, but as of yet, they have not made much headway.

Joel Kotkin is executive editor of NewGeography.com and Distinguished Presidential Fellow in Urban Futures at Chapman University, and a member of the editorial board of the Orange County Register. He is author of The City: A Global History and The Next Hundred Million: America in 2050. His most recent study, The Rise of Postfamilialism, has been widely discussed and distributed internationally. He lives in Los Angeles, CA.

This piece originally appeared at Forbes.

Creative Commons photo “Engineers” by Flickr user ensign_beedrill