The sustainable city of the future will rest on the revival of traditional institutions that have faded in many of today’s cities.

Ellen Moncure and Joe Wong first met in school and then fell in love while living in the same dorm at the College of William and Mary. After graduation, they got married and, in 1999, moved to Washington, D.C., where they worked amid a large community of single and childless people.

Like many in their late 20s, the couple began to seek something other than exciting careers and late-night outings with friends. “D.C. was terrific,” Moncure recalled over lunch near her office in lower Manhattan. “It was an extension of college. But after a while, you want to get to a different ‘place.’”

The “place” Ellen and Joe looked for was not just a physical location but something less tangible: a sense of community and a neighborhood to raise their hoped-for children. Although they considered suburban locations, as most families do, ultimately they chose the Ditmas Park neighborhood of Brooklyn, where Joe had grown up.

At first, this seemed a risky choice. While Joe was growing up in the 1980s, the neighborhood — a mixture of Victorian homes and modest apartments — had become crime-infested. The old families were moving out, and newer ones were not replacing them. Yet Joe’s Mom still lived there, and they liked the idea of having grandma around for their planned-for family.

In a city that has been losing middle-class families for generations, the resurgence of places like Ditmas Park represents a welcome change. In recent years, child-friendly restaurants and shops have started up along once-decayed Cortelyou Road. More important, some local elementary schools have shown marked improvement, with an increase in parental involvement and new facilities.

Even in hard economic times, the area has become a beacon to New York families, as well as singles seeking a community where they will put down long-term roots. “There’s an attempt in this neighborhood to break down the city feel and to see this more as a kind of a small town,” notes Ellen. “It may be in the city, but it’s a community unto itself, a place where you can stay and raise your children.”

The Decline of the Urban Middle Class

The rise of neighborhoods like Ditmas Park suggests that cities can still nurture and accommodate a middle class. Yet sadly this trend continues to fight an uphill battle against a host of forces from high taxes and regulation to poor schools, highly bifurcated labor markets, and the scourge of crime.

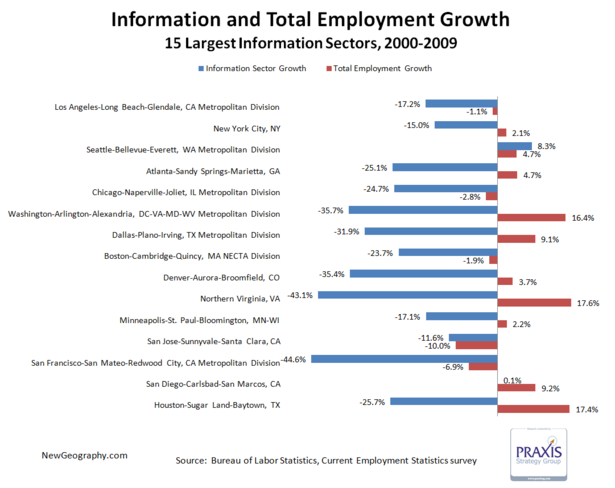

These problems can be seen in the migration numbers. A demographic analysis conducted by my colleagues at the Praxis Strategy Group over the past decade found that New York and other top cities — including Chicago, Los Angeles, San Francisco, and Boston — have been suffering the largest net out-migration of residents of virtually all places in the country, albeit the pattern has slowed with the recession.

It’s astonishing that, even with the many improvements over the past decade in New York, for example, more residents left its five boroughs for other locales in 2006 than in 1993, when the city was in demonstrably far worse shape. In 2006, the city had a net loss of 153,828 residents through domestic out-migration, compared to a decline of 141,047 in 1993, with every borough except Brooklyn experiencing a higher number of out-migrants in 2006.

Since the 1990s virtually all the gains made in the New York economy have accrued to the highest income earners. Overall, New York has the smallest share of middle-income families in the nation, according to a recent Brookings Institution study; its proportion of middle-income neighborhoods was smaller than any metropolitan area, except for Los Angeles.

Much the same pattern can be seen in what has become widely touted as America’s “model city,” President Obama’s adopted hometown of Chicago. The city has also experienced a rapid loss of its largely white middle class at a rate roughly 40 percent faster than the rest of the country.

Although there has been a considerable gentrification in some pockets around Lake Michigan, Chicago remains America’s most segregated big city. In contrast to the president’s well-integrated cadre of upper-class African Americans, Chicago’s black population remains among the poorest, and most isolated, of any ethnic population in America.

And like other American cities, Chicago now has a growing glut of “luxury” condos, a pattern that became evident as early as 2006 and has now, as Chicago magazine put it, “stalled” as a result of a “perfect storm” of toughened mortgage standards, overbuilding, job losses, and rising crime.

Yet there could be some good from the current crisis. Considerable drops in urban rents and residential housing prices should ease the burdens on those who struggle with extremely high prices and taxes. Younger people, including families, may now be able to consider whether a home in Brooklyn, Chicago’s Wicker Park, or Los Angeles’ Studio City might now be affordable and desirable enough to eschew the move to the suburbs.

The Cost of Being Urban

In doing scores of interviews recently for a report on New York’s middle class, my coauthor Jonathan Bowles of the Center for an Urban Future and I ran into many people who were considering moving out of the city or had friends who had recently left. This seems particularly true in the remaining middle-class enclaves in the outer boroughs.

“Almost all the friends I grew up with have moved to Mahopac or Yorktown [in the Hudson Valley],” says Jimmy Vacca, a member of the City Council who represents communities in the Northeast Bronx such as Throgs Neck and Pelham Parkway. “There’s a flight out by many middle-class people because of the schools. A couple gets married and by the time their children gets to age five, they move.”

Costs, particularly relating to child-raising, are killing the urban middle class. Urban residents generally pay higher taxes and more for utilities, insurance, trash, and sewer than those living elsewhere. Manhattan is by far the most expensive urban area in the United States, with an average cost of living that is more than twice as much as the national average; San Francisco, another city that has seen large-scale middle-class flight, ranks second. The Washington, D.C. area, Los Angeles, and Boston also suffer extremely high living costs.

These costs are most onerous on the middle class, particularly those with children. This can be seen in the rapidly declining numbers of students in most urban school districts, including such hyped success stories as Chicago, Seattle, Portland, Washington, and San Francisco. Over the past seven years, for example, Chicago’s school system, which was run by new Education Secretary Arne Duncan, has declined by 41,000 students.

America’s core cities — including the borough of Manhattan in New York — boast among the lowest percentage of children under 17 in the nation. Although Manhattan had a much discussed “baby boomlet” (the borough’s number of toddlers under the age of 4 grew 26 percent between 2000 and 2004), once children over 5 are taken into account, Manhattan’s under-age population is well under the national average. This indicates there may be a process of exhaustion — both mental and financial — as the costs of raising children drain family resources.

The real issue for the urban middle class is not having babies but being able to sustain their families as the children age and as families expand. One reason: many middle class urbanites spend tens of thousands of dollars a year in additional expenses that those in other cities as well as surrounding suburbs often avoid. For instance, since most middle-class families in big cities today need to have two working parents just to get by, child care becomes a necessity for those without grandparents or other relatives to look after young children. In places like Chicago, Washington, Boston, San Francisco, New York, or Los Angeles these costs typically run from $13,000 to $25,000 per child annually.

Later many of these same families, if they choose to stay, must then contemplate shelling out considerable sums to send their children to private schools, particularly after the elementary level. This can add from a few thousand dollars to $30,000 a year to their annual costs — and with no tax benefit.

Do Cities Need a Middle Class?

Ultimately, in good times or bad, cities have to want a middle class to have one. And politicians, if asked, will genuflect to the idea of maintaining a middle class, yet their actions — on taxes, regulations, schools, development — suggest otherwise.

Indeed, in reality most urban areas have focused on creating what New York Mayor Michael Bloomberg famously dubbed the “luxury city.” To pay for often inflated public employee costs, the luxury city can only survive off the wealthy and on other groups — empty nesters, singles and students — who demand relatively little in the way of basic services like schools and public health facilities.

City planners and urban developers favor the unattached: the “young and restless,” the “creative class,” and the so-called “yuspie” — the young urban single professional. Champions of the unattached suggest that companies and cities should capture this segment, described by one as “the dream demographic,” if they wish to inhabit the top tiers of the economic food chain.

Another key group coveted by cities are the legions of baby boomers who have already raised children. No longer cohabiting with offspring, they are expected to give up their dull family existence and rediscover the allure of a fast-paced, defiantly “youthful” lifestyle. The new retirees, suggests luxury homebuilder Robert Toll, “are more hip-hop and happening than our parents.” They are more interested in indulging “the sophistication and joy and music that comes with city dwelling, and doesn’t come with sitting in the ’burbs watching the day go by.”

A Demographic Dead End?

This whole approach has severe limitations. Despite an enormous amount of publicity about empty nesters moving back to the city, surveys conducted by the housing industry find that most aging boomers — upwards of 70 percent — are aging in place, mostly in the suburbs. The numbers moving back into the urban core remain negligible, except in the pages of urban booster publications like The New York Times.

The young singles provide a more promising demographic for cities. But even here time may be running out. This will be even more evident between 2010 and 2020, when the millennial generation hits their 30s and early 40s and enter the prime years for family formation. Surveys of the cutting edge of this group — the other large age cohort in the population — show that most prefer a single-family home and, like their parents, seem most likely to head to the suburbs.

But perhaps most troubling of all is what this means in terms of the historic role of cities as incubators of upward mobility. Back in the 1960s, Jane Jacobs could still predict that Latino immigrants to New York, mainly from Puerto Rico, would inevitably make “a fine middle class.” Yet four decades later in the Bronx, the city’s most heavily Latino county, roughly one in three households lives in poverty, the highest rate of any urban county in the nation.

On the other extreme, in Manhattan, where the rich are concentrated, the disparities between the classes have been rising steadily. In 1980 it ranked 17th among the nation’s counties for social inequality; today it ranks first, with the top fifth of wage earners earning 52 times that of the lowest fifth, a disparity roughly comparable to that of Namibia.

The University of Chicago’s Terry Nichols Clark, one of the most articulate advocates for this new urban pattern, says cities should focus on acting not so much as vehicles for class mobility, but as “entertainment machines” for the privileged. For these elite residents, the lures are not economic opportunity, but rather “bicycle paths, beaches and softball fields,” and “up-to-the-date consumption opportunities in the hip restaurants, bars, shops, and boutiques abundant in restructured urban neighborhoods.”

In this formulation cities become the domicile primarily of the young, the rich (and their servants), as well as those members of the underclass who persist in hanging around. What emerges, in the end, is a city largely without children, particularly of school-age, and with a diminishing middle class. Ironically, these are places that, despite celebrating diversity, actually could end up as hip, dense versions of the most constipated suburb imaginable.

This shift will also limit the economic functions of certain elite cities. Cost pressures, for example, have already helped Houston to replace New York and Los Angeles as the nation’s energy capital; in the future, although now humbled by the collapse of Wachovia, more middle class-oriented Charlotte, as well as other cities, could continue to gain jobs in the post-bust financial sector. Charlotte real estate developer John Harris suggests the city can compete against an expensive metropolitan region not only at the top levels of management but across the board. “It’s hard to be a mass employer in San Francisco,” he notes.

Joe Gyourko, a real estate professor at the Wharton School, suggests this elite model of urbanism will spread to other favored places such as Portland, Seattle, and possibly Austin. In all these places, we may be seeing the emergence of a European-style pattern of elite urbanism in the core, with a growing concentration of low-wage workers in the least favored parts of the urban periphery.

The City of Aspiration

Even if such a model proves sustainable, it certainly means a major change for American urbanism. Unlike most urban cultures, that of the United States has been dominated not by the dictates of princes or priests, but by the efforts of ambitious entrepreneurs and migrants.

American cities have been driven by a protean, ever-shifting commercial and middle-class culture, willing to break the bonds of tradition. As the great sociologist E. Digby Baltzell noted, the population in New York and other American cities has been “heterogeneous from top to bottom.” Social mobility, Baltzell said, constituted the fundamental reality of American urbanism.

In this country, cities emerged as the principal North American bastion for those who sought to improve their lives. As historians Charles and Mary Beard noted, “All save the most wretched had aspirations.”

Such cities often were not inherently pleasant or culturally edifying. Although its wealth would propel it to one day become the world’s cultural capital, visitors from more genteel Philadelphia and Boston often regarded 19th-century New Yorkers as crass and money-oriented.

The new cities on the opportunity frontier — Chicago, Cleveland, Cincinnati — were, if anything, even more egalitarian. After two years in Cincinnati, British writer Frances Trollope deplored how “every bee in the hive is actively employed in the search for honey…neither art, science, learning, nor pleasure can seduce them from their pursuit.” Chicago, a Swedish visitor commented in 1850, was “one of the most miserable and ugly cities” of America.

Yet these places were ideal for taking advantage of new technologies from mass manufacturing to trains and the telegraph. They created dynamic societies that provided huge opportunities for vast waves of immigrants, who by 1890 accounted for as much as half of the nation’s urban dwellers.

The newcomers were joined by others from rural America, including, by the early 20th century, many African Americans. The “Great Migration” of African Americans from the rural south, noted Gunnar Myrdal in 1944, created “a fundamental redefinition of the Negro’s status in America.” Urban life had its horrors, but in the cities it became increasingly difficult to restrict a person into “tight caste boundaries.” African-American migrants from the South may have been different in many ways from newcomers from Italy, Ireland, or Russia, but their fundamental aspirations were often very much the same.

The Key to a Middle-Class Comeback: The Power of Plain Vanilla

Compared to the dismal decline in the 1970s and early 1980s, urban prospects have improved, particularly in primary urban areas such as Chicago, New York, and San Francisco. Yet, if these and other cities are to sustain their momentum, they need to look beyond “the luxury city” to the potential of less glamorous neighborhoods that can attract the middle class and people with families.

These “plain vanilla” neighborhoods include many places that managed to resist the urban decay of the 1970s and in many cases have begun to enjoy a steady resurgence. These include, for example, large swaths of Brooklyn and Queens, as well as the lovely, park-blessed sections of south and west St. Louis, or scattered Los Angeles neighborhoods in places like the San Fernando Valley.

But these communities can only grow if cities focus on those things critical to the middle class such as maintaining relatively low density work areas and shopping streets, new schools, and parks.

This would require a massive shift in urban priorities away from the current course of subsidizing developers for luxury mega-developments, new museums, or performing arts centers. To maintain and nurture a middle class, cities need to look at the essentials that have made great cities in the past and could once again do so in the future.

The New Urban Middle Class

Perhaps the other key question is what constitutes the economic base for the people who might settle and remain in cities. It’s clear that many traditional industries — heavy manufacturing, warehousing — as well as middle-management white collar jobs will diminish in the future. But it is possible to imagine the rise of a new kind of urban economy built around people working in small firms, or independently in growing fields such as information, education, healthcare, and culture, or as specialists in a wide array of business services.

These are professions that continued to grow in many older cities, even as other fields declined. In San Francisco, for example, by 2006 there were an estimated 70,000 home-based businesses and a thriving culture of self-employed “Bedouins” working in post-industrial professions. These self-employed people, noted one study, were critical to helping the city withstand the ill effects of the post-2000 dotcom collapse.

Similarly, the close-in communities of the San Fernando Valley of Los Angeles are home to large contingents of entertainment industry workers, many of them self-employed. According to studies by California State University’s Dan Blake, up to 60 percent of all L.A.-area workers in this highly dispersed industry reside somewhere in this sprawling urban region made up largely of post–World War II single-family houses. Workers in media, graphic arts, and other specialized services have also been among the few groups of middle and upper-middle income earners to see rapid growth in New York’s outer boroughs.

These post–industrial age artisans — along with more traditional parts of the middle class such as civil servants, teachers, nurses, and other service workers — could provide the critical residential base for the plain vanilla urban neighborhoods’ work. Neither rich nor poor, these artisans could use the new telecommunications net to access clients who may exist in the sprawling suburban rings, throughout the United States, or overseas.

Cities of the Future

You can see this emerging reality in places like Ditmas Park, Brooklyn. Nelson Ryland, a film editor with two children who works part-time at his sprawling turn-of-the-century Flatbush house, suggests that the key to an urban revival lies not in the spectacular but in the mundane. “It’s easy to name the things that attracted us — the neighbors, the moderate density,” he says over coffee in a house close to that occupied by Ellen and Joe. “More than anything it’s the sense of community. That’s the great thing that keeps people like us here.”

This “sense of community” will become the key currency of sustaining urban communities. Such middle-class sensibilities get short shrift by urban scholars such as Richard Florida, who argue that in the so-called “creative age” places of residence should be “leased” like cars. In his mind, single-family homes, the ideal of homeownership, should be replaced “by a new kind of housing” that embraces higher forms of density without long-term commitment to a particular residence or location.

In fact, the sustainable city of the future will depend precisely on commitment and long-term residents. It also will rest on the revival of traditional institutions that have faded in many of today’s cities. Churches — albeit often in reinvented form — help maintain and nurture such communities. Similarly, extended family networks will be critical to future successful urban areas. As Queens resident and real estate agent Judy Markowitz puts it, “In Manhattan people with kids have nannies. In Queens, we have grandparents.”

The modest and mundane ties between people that exist in such places represent the key to reviving America’s urban regions in the coming generation. It is in our urban neighborhoods — not in the glamour zones and high-end downtowns — that our country’s cities can find a new life and purpose in the 21st century.

This article originally appeared at American.com.

Joel Kotkin is executive editor of NewGeography.com and is a presidential fellow in urban futures at Chapman University. He is author of The City: A Global History and is finishing a book on the American future.

and is finishing a book on the American future.

. His next book, The Next Hundred Million: America in 2050, will be published by Penguin early next year.