With the possible exception of health care reform, no major issue presents more political opportunities and potential pitfalls for President Barack Obama than energy. A misstep over energy policy could cause serious economic, social and political consequences that could continue over the next decade.

To succeed in revising American energy policy, the president will need to try to triangulate three different priorities: energy security, environmental protection and the need for economic growth. Right now, the administration would like to think it could have all three, but these concerns often collide more than they align.

A president should have no higher priority than to ensure that America becomes more independent from foreign producers, particularly those outside North America. This represents a great opportunity to diverge from the failure of the Bush administration to reduce this dependence and encourage conservation.

Instead, the best course could be called an “all of the above” strategy. This would embrace not only conservation and investment in renewable fuels but also aggressive expansion of the electric grid, the domestic fossil fuel industry and nuclear power. In particular, the country should focus on exploiting our vast reserves of relatively clean natural gas and drive technologies that could also clean up emission from coal, our other large resource.

Instead of promoting fossil fuel development, environmental lobbyists — and Obama — like to talk about “green jobs.” Although green elements need to be integrated into all walks of economic life, the notion that green jobs can provide economic salvation seems more like a marketing strategy than one based on reality.

Given current energy prices, large-scale numbers of green jobs can be created only through huge subsidization, the costs of which would, of course, be born by other parts of the economy. At the same time, jobs lost in fossil fuel production and manufacturing because of the high costs associated with renewables would most likely far outweigh any imaginable surge of green jobs.

A recent study conducted in Spain, another country with a history of strong subsidies for renewable fuels, found that the money invested in green jobs actually cost so much that the overall employment effects were negative. Increasingly, the “green jobs” mantra seems like a story we tell our children to get them to sleep.

The mantra also obscures the critical fact that the true goal of the environmental lobby is, above all, to shrink the much detested “carbon footprint” of people and communities. People like Obama’s science adviser, John Holdren, do not place much priority on maintaining much of the present American way of life. An acolyte of the many-times-wrong neo-Malthusian Paul Ehrlich, Holdren has promoted the “de-development” of Western societies as a way to lower carbon emissions and redistribute the world’s wealth.

Such an approach might be popular at academic soirees or even among some investment bankers who see their future in Shanghai as opposed to Saginaw or Sacramento. It may prove a bit less popular among those, particularly in the middle and working class, who might not welcome seeing their families and communities de-developed.

This should be obvious to the president and the clever political tacticians around him. Recent polls reveal that voters now rate global warming among their 20 least-critical concerns. Not surprisingly, the economy and jobs ranked as the top two.

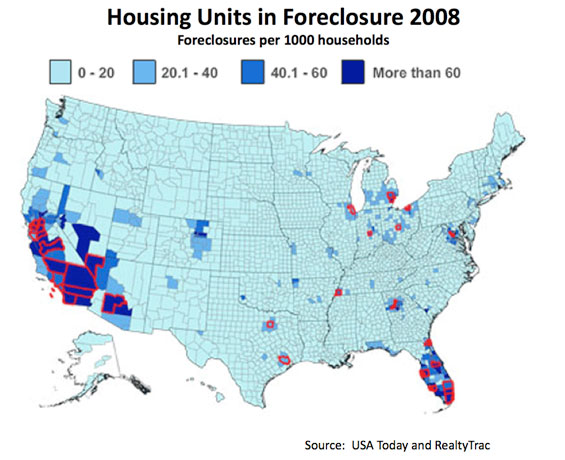

There are also serious regional issues to consider. Areas with economies tied to fossil fuels — mainly in Texas, the Great Plains, the Southeast and Appalachia — view the issue differently than do places like Manhattan, San Francisco or Chicago’s Gold Coast, whose residents can afford much higher energy prices and have few ties to traditional productive industries.

As leader of both the country and his party, the president will have to consider these regional and class divides. The Republicans may be irrelevant, but the swelling ranks of more-pragmatic Democrats from Western, Southern and exurban districts cannot be so easily dismissed.

In this sense, the possibility of the election next year of Houston Mayor Bill White, a Democrat, to the Senate represents more of a threat to the green lobby than a Republican victory does. White, like many Texas Democrats, has close ties to the energy industry and has already expressed grave misgivings about the administration’s renewables-obsessed carbon emissions policies.

Given growing opposition in Congress, green groups and their allies in legal circles now argue that the administration can transcend the messy political process by imposing a strict anti-greenhouse-gas policy through the Environmental Protection Agency apparat. This has the virtue of allowing the president to avoid direct confrontation with many congressional Democrats but leaves power firmly in the hands of zealots for whom both energy independence and economic growth are less-than-compelling priorities.

Ultimately, energy policy is too important to the economy and security to be left in the hands of bureaucratic zealots and their allies. It is up to the president to forge an energy program that, while looking toward renewables in the long run, does not sacrifice the livelihoods of millions of American workers today or leave our country ever more susceptible to the machinations of hostile foreign powers.

This article originally appeared at Politico.

Joel Kotkin is executive editor of NewGeography.com and is a presidential fellow in urban futures at Chapman University. He is author of The City: A Global History and is finishing a book on the American future.