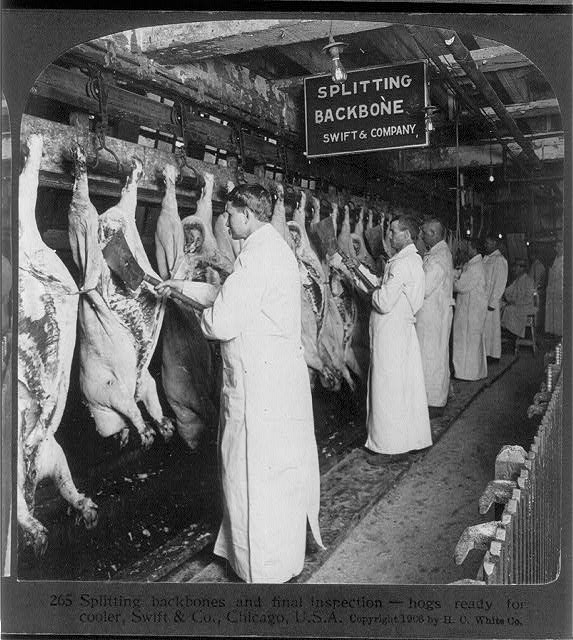

Upton Sinclair’s 1906 novel The Jungle was intended to inform the larger American public of the miserable working environment and sub survival wages of Chicago’s meat packing employees. The popular response was huge and lead to new government agencies and protections, but not the kind Sinclair had hoped for. By describing the dangerous and unhealthy conditions in slaughterhouses he meant to elicit sympathy for the workers who were denied adequate pay and were routinely maimed or killed on the job with no recourse to improved safety, medical care, or compensation.

What the outraged American public focused on instead was tainted meat from unsanitary facilities. The general population was far less interested in the plight of the Lithuanian immigrant workers Sinclair described than the wholesomeness of the food supply. The Federal Food and Drug Administration was signed in to law by President Theodore Roosevelt in direct response to the uproar over the novel. Making life better for the underclass wasn’t nearly as gripping as making sure fingers weren’t getting ground up into the sausages.

It wasn’t until the Great Depression of the 1930’s that government – at the insistence of American voters – actually began to create serious labor laws to lift the status of ordinary workers. The pain of being on the wrong end of the stick had migrated from an unloved minority to too many people who thought they were better off – until they weren’t. And it wasn’t until the onset of World War II when labor became scarce relative to the need for wartime production that wages began to rise.

Americans don’t actually care about the poor and never have. It’s important to keep this in mind. I recently found this comment on an economics website. It sums up the standard response to today’s struggle over increasing inequality.

“Millions of very decent and good people can’t afford to live in upper middle class cocoon cities like what San Francisco is becoming. We need to allow the responsible members of the shrinking middle class and growing lower classes to isolate themselves from the worst members of the lower classes. People who lack the buying power to move to nice protected towns full of professional workers need ways to separate themselves from social pathology. Our current elites inflict section 8 housing and a growing immigrant lower class on the responsible people who can’t afford bubble city life. This is just so wrong of them. Our elites are our enemies.” Source

So the problem is that elites are segregating themselves from the declining middle class – and the proposed solution is to provide a separate bubble for the squeezed former middle class to retreat to so they can segregate themselves from people lower down the ladder. Huh? I suppose I have to ask… who decides who is struggling but worthy and who is part of the “social pathology”? And what mechanism might deliver the protection the commentator desires?

As a society we don’t reach for solutions that might address the underlaying structural flaws that create the underclass or the elites. Instead we look for ways deserving individuals can distance themselves from the effects of those structural defects. We assume a big chunk of the population will be left behind and we don’t mind so long as it’s the undeserving that get screwed. That’s always been our de facto national policy.

This piece first appeared on Granola Shotgun.

John Sanphillippo lives in San Francisco and blogs about urbanism, adaptation, and resilience at granolashotgun.com. He’s a member of the Congress for New Urbanism, films videos for faircompanies.com, and is a regular contributor to Strongtowns.org. He earns his living by buying, renovating, and renting undervalued properties in places that have good long term prospects. He is a graduate of Rutgers University.