Express coach lines like BoltBus and Megabus have grown dramatically in recent years, providing millions of Americans with new mobility options. When the subject of competition between bus and train arises, however, many transportation wonks instantly become minimizers. Some cite growing rail traffic to make the case that this competition hardly matters. Others point to severe congestion on the Northeast Corridor (NEC)—Amtrak’s busiest route—to build the argument that attempting to lure passengers from buses to trains is a pointless exercise. Still, others note that trains are roomier and more comfortable than buses. This implies that the latter will forever be a last-resort option.

There may be a grain of truth in some of these assertions, but the fact is that today’s travel market is increasingly cutthroat. Neither Amtrak nor bus lines can continue to expect robust growth of traffic merely by doing more of the same. The national average price of gasoline has, stubbornly, remained below $2.50 for more than two years, nullifying much of the advantage buses and trains had as relatively more fuel-efficient modes. The average round trip ticket price for airline trips fell to $361.20 in 2016, down almost $20 from 2015.

In this tough environment, air and automobile travel has grown while bus and rail traffic has ebbed. After years of steady growth, Amtrak experienced a slight drop in passenger miles of traffic during its 2016 fiscal year, despite an improving economy. FirstGroup, owner of Greyhound, which operates the popular express coach line BoltBus, and Stagecoach Ltd., which owns Megabus, both experienced revenue drops from their North American operations during the 2016 fiscal year.

That means the gloves are coming off in the fight for market share. Amtrak is experimenting with new pricing strategies and has added free Wi-Fi to most routes, matching the amenities of express coach lines. BoltBus and Megabus have also lowered fares and created apps allowing travelers to quickly change their reservations at only a nominal cost. Megabus has also rolled out reserved seating, allowing passengers to choose a specific seat – even one at a table – when booking to appeal to those wanting to work on their trip or who are concerned about a lack of comfort and privacy.

Amtrak & Express Coaches – What’s Really Going On?

Intrigued at the shifting contours of bus versus rail competition, I evaluated the competition between Amtrak and relatively new express coach lines. Five results stand out:

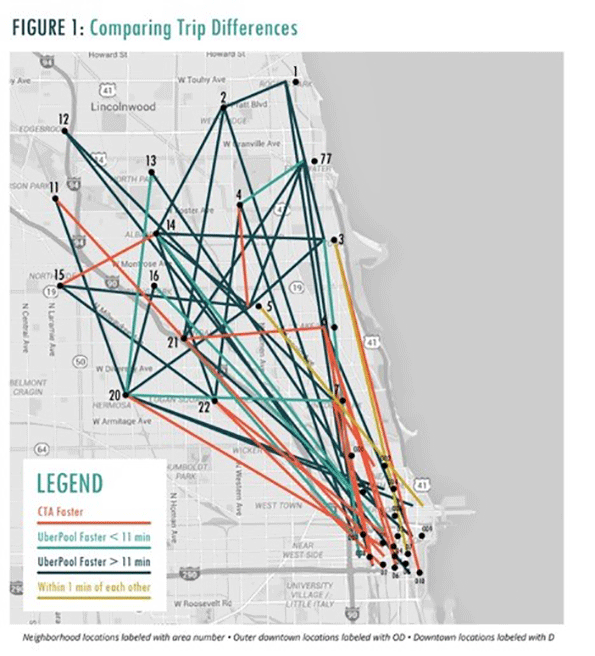

1) On short- and medium-distance corridors with several daily trains, competition with Amtrak from express coach lines is fierce. Among the 4,854 miles of such corridors with more than one Amtrak train each day, almost three quarters (74%) have parallel express coach service, with Megabus easily the most pervasive. The entire NEC operation runs head-to-head against not only BoltBus and Megabus, but smaller lines like Go Buses as well. Every mile of the Pacific Northwest’s Cascade Corridor is traversed by BoltBus, while Amtrak’s busiest medium-distance corridors in the Carolinas and the Midwest are served by Megabus’ double-deckers.

Click here for an enlarged map.

By comparison, on long-distance routes and corridors having only one daily train, only about a third of mileage is subject to express coach competition. You will not find express coach lines paralleling any stretch of the Chicago – Los Angeles Southwest Chief route, yet every mile of the Crescent’s New York – New Orleans route is covered. Still, new bus lines are regularly popping up.

2) The “sweet spot” for express bus lines are 125 – 300 mile routes, which allow for trips between 2.5 and 6 hours. Anything longer can seem insufferable in a bus, while shorter trips are often avoided due to many travelers’ desire to stay flexible. Plus, on short-hop routes, a large portion of the ride can be spent on traffic-clogged urban expressways, making travel times more unpredictable.

This means than when trips are less than 125 miles, the train often wins. Both BoltBus and Megabus have withdrawn from the approximately 120 mile Los Angeles – San Diego route, and they provide scant competition on the Oakland – Sacramento “Capitol Corridor” and Chicago – Milwaukee “Hiawatha Corridor”, running no more than a pair of daily trips. Express coaches are more popular between New York – Philadelphia (90 miles) partially due to abnormally high train fares on this route, which often run four times the normal bus fare.

3) Amtrak’s greatest advantage lies in serving intermediate stops. Another bright spot for Amtrak is that express coaches bypass many places generating extensive Amtrak business. Megabus, for example, runs express between Chicago and St. Louis (except for rest stops), while Amtrak calls on ten intermediate points, including Springfield, IL, the state capital. A similar pattern exists along other corridors.

Express coach bus lines reach deeper in the NEC, serving not only Boston, New York, Philadelphia, Baltimore and Washington, D.C., but smaller points as well. Still, the railroad’s “string of pearls” network allows for direct trips between dozens of city combinations in a way not possible on express coaches, which tend to run direct to major hubs like New York.

4) Express coach bus lines no longer operate predominately from Amtrak’s doorstep, which makes for a fairer fight. It may have once been true that express bus lines poached passengers eager to save a few bucks by leaving from curbs outside major train stations, but this is now rare. Almost two thirds of Megabus departures leave from points at least a half-mile away from the train. In New York, these buses now leave from about a mile away, on Manhattan’s west side. Only about a quarter of express coach departures operate from points a third-of-a-mile or less from Amtrak. This is the case in Boston and Washington, D.C., where dedicated bus terminals are connected to train stations.

What’s more, development pressures and other urban issues are pushing the express coach lines to more remote spots. Earlier this year, for example, Megabus moved its loading zone to a location four blocks farther away from Chicago’s Union Station, where it had been located since its inception.

Driving Up Demand

Increasing demand over the next several years could take the sting out of the upsurge in competition. Oil prices are expected to inch up and the economy is improving. Moreover, working together could help give these modes a competitive edge in some circumstances. Buses can fill gaps in train schedules to provide better ground-travel options (while respecting federal rules limiting Amtrak’s involvement in the motor coach business). Intercity buses could more intensively feed Amtrak routes, as is done in California, who pioneered this approach, and Michigan, which has a similar strategy.

But the bigger story is that bus-train competition has left the station and is speeding down the tracks. Expect bus lines to add new stops and continue to roll out amenities, while Amtrak works to boost frequency and speed, and grapple with its nemesis—delays—without the expectation of significant increases in federal funding over the short term. May the best mode win!

Joseph Schwieterman, Ph.D., is professor of Public Services and director of the Chaddick Institute for Metropolitan Development at DePaul University in Chicago. He is the author of several books on railroads and a widely read annual report on the intercity bus industry.

Photo by Chaddick Institute.