The San Jose metro is adding jobs at a faster clip than any other large metro area in the U.S. since the recession. Houston, Austin, Detroit — and a handful of other metros — have also been stellar performers the last few years. But how much of the job growth in these and other metros can be explained by unique regional factors rather than national trends?

To answer that question, EMSI used a standard economic analysis method called shift share, focusing on overall job change from 2010 to 2012. We followed the same methodology that we used to show which states are gaining in competitiveness. However, for this post, we looked at the 100 most populous metropolitan statistical areas (MSAs) in the U.S.

The goal is to see which metros are becoming more competitive (that is, gaining a larger share of total job creation) and which are losing their share of the jobs being created. We ranked all 100 metros based on the overall competitive effect and what percentage of jobs (from 2010-2012) are based on competitive effects.

Our Approach

Shift-share analysis, which can also be referred to as “regional competitiveness analysis,” helps us distinguish between growth that is primarily based on big national forces (the proverbial “rising tide lifts all boats” analogy) vs. local competitive advantages. The primary components of shift share are as follows:

- Industrial Mix Effect — This represents the share of regional industry growth explained by the growth of the specific industry at the national level.

- National Growth Effect — This explains how much of the regional industry’s growth is explained by the overall growth of the national economy.

- Expected Change – This is simply the rate of growth of the particular industry at the national level (equals the sum of the industrial mix and national growth effects).

- Regional Competitiveness Effect — This explains how much of the change in a given industry is due to some unique competitive advantage that the region possesses, because the growth cannot be explained by national trends in that industry or the economy as whole.

Read more on shift share in this article: Understanding Shift Share.

About the Data

The infographic and table below display aggregate industry data for the 100 most populous MSAs from 2010-2012. To generate our ranking, we summed the overall competitive effect for each broad 2-digit industry sector (e.g., agriculture, manufacturing, health care, construction, etc.) and added them together to yield a single MSA-wide number that indicates the overall competitiveness of the economy as compared to the total economy. We calculate the competitive effect by subtracting the expected jobs (the number of jobs expected for each MSA based on national economic trends) from the total jobs. The difference between the total and expected is the competitive effect. If the competitive effect is positive, then the MSA has exceeded expectations and created more jobs than national trends would have suggested. It is therefore gaining a greater share of the total jobs being created. If the competitive effect is negative, then the MSA is below what we would expect given national trends. In this case the MSA is losing a greater share of the total jobs being created.

The Results

Top Five

The two metros at the top have been economic stalwarts in recent years. After that, our analysis revealed a couple surprises.

Note: The figure in parentheses is the percentage of total 2012 jobs that are due to growing (or declining) competitiveness from 2010-2012.

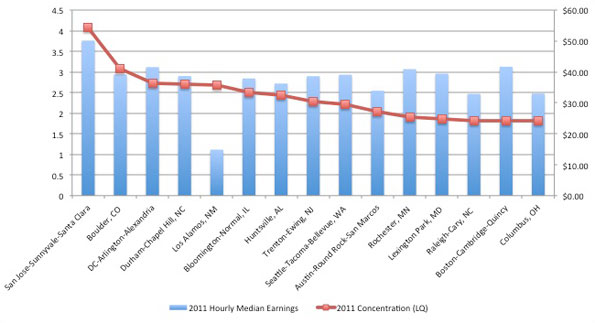

1. San Jose-Sunnyvale-Santa Clara, Calif. (3.5%) – The heart of Silicon Valley has created 35,803 more jobs than expected since 2010, thanks largely to the information sector (most notably, internet publishing and broadcasting and web search portals and software publishers). Electronic computer manufacturing has also seen more-than-expected growth in the San Jose metro area, as has warehouse clubs and supercenters and private elementary/secondary schools.

In other words, the high-paying jobs generated in the tech sector appear to be leading to more jobs in the retail trade and education sectors than we would expect based on national trends.

2. Austin-Round Rock-San Marcos, Texas (3.4%) – Save for government and retail trade, every broad sector in the Austin metro area has exceeded expectations. The result is 30,472 more jobs than expected from 2010 and 2012. The strongest sub-sectors in Austin are wired telecommunications carriers; wholesale trade agents and brokers; and corporate, subsidiary, and regional managing offices.

3. Bakersfield, Calif. (3.1%) – Bakersfield has one of the highest unemployment rates (12%) among all metropolitan areas. But better-than-expected job growth in the construction and agricultural sectors has propelled this San Joaquin Valley metro to third in our ranking. The agriculture boom has been seen most in crop production and farm labor contractors/crew leaders. Meanwhile, much of the surprising construction growth has been in two sub-sectors — oil and gas pipeline and related structures construction and electrical contractors and other wiring installation contractors.

4. Provo-Orem, Utah (2.8%) – Next is Provo-Orem, which has the fourth-fewest total jobs of any top 100 metro (an estimated 211,639). This metro area just south of Salt Lake City has seen surprisingly large job gains in professional, scientific, and technical services (see here for more); administrative and support services; specialty trade contractors; state/local government; and computer and electronic product manufacturing.

A note on Utah: Provo-Orem, Salt Lake City (No. 6), and Ogden-Clearfield (No. 29) are all in the upper third of the top 100 metros in competitiveness.

5. Houston-Sugar Land-Bayton, Texas (2.7%) — No metro in America has added more jobs than expected since 2010 than Houston (79,815). These jobs aren’t coming in oil & gas extraction or support activities for mining — Houston’s actually doing worse than expected in these two booming industries — but rather in health care, accommodation/food service, and manufacturing. In particular, home health care services, offices of physicians, restaurants, employment services, and fabricated metal product manufacturing are far surpassing expected growth.

The rest of the top 10:

- Salt Lake City, Utah (2.6%)

- Grand Rapids-Wyoming, Mich. (2.4%)

- Omaha-Council Bluffs, Neb.-Iowa (2.4%)

- Raleigh-Cary, N.C. (2.1%)

- Detroit-Warren-Livonia, Mich. (2.1%)

Bottom Five

The other side of our ranking is dominated by Southern metros, particularly those in Florida. But an even more common thread with the poor performers is the greater-than-expected losses in administrative and support services, a sub-sector that comprises “establishments engaged in activities that support the day-to-day operations of other organizations,” according to the BLS.

100. Augusta-Richmond County, Ga.-S.C. (-3.9%) — This metro has lost nearly 9,000 more jobs than expected, most in waste treatment and disposal, employment services, and services to buildings and dwellings.

99. Albuquerque, N.M. (-3.4%) — Albuquerque has fared worse than Augusta in total unexpected jobs lost (13,691), with the losses coming in similar areas — employment services, architectural/engineering services, electrical/electronic goods merchant wholesalers, and services to buildings and dwellings. Construction and government (local and federal) have also taken worse-than-expected hits.

98. Palm Bay-Melbourne-Titusville, Fla. (-3.3%) — Like Augusta and Albuquerque, the Palm Bay-Melbourne area has done poorly in administrative and support services (particularly facilities support services) and construction (particularly specialty trade contractors).

97. Lakeland-Winter Haven, Fla. (-2.4%) — Once again, this Florida metro has seen massive (and unexpected) decline in admin and support services, most notably employment services. Government, manufacturing, and construction have also lost more jobs than expected since 2010.

96. Modesto, Calif. (-2.3%) — This Central Valley metro area has struggled more than expected in manufacturing (especially the making of snack foods and frozen foods). Elementary and secondary schools have also suffered.

The rest of the bottom 10:

- Milwaukee-Waukesha-West Allis, Wis. (-2.3%)

- Providence-New Bedford-Fall River, R.I.-Mass. (-2.2%)

- Little Rock-North Little Rock-Conway, Ark. (-2.1%)

- Birmingham-Hoover, Ala. (-2.0%)

- St. Louis, Mo.-Ill. (-2.0%)

For the full list of the largest 100 metros, see our accompanying graphic or the table below.

| MSA |

2012 Jobs

|

Expected Jobs (2012)

|

Competitive Effect

|

% of Jobs Due to Comp. Effect

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Source: QCEW Employees, Non-QCEW Employees & Self-Employed – EMSI 2012.3 Class of Worker | ||||

| San Jose-Sunnyvale-Santa Clara, CA |

1,014,025

|

978,222

|

35,803

|

3.5%

|

| Austin-Round Rock-San Marcos, TX |

894,864

|

864,392

|

30,472

|

3.4%

|

| Bakersfield-Delano, CA |

320,625

|

310,730

|

9,895

|

3.1%

|

| Provo-Orem, UT |

211,639

|

205,722

|

5,918

|

2.8%

|

| Houston-Sugar Land-Baytown, TX |

2,952,899

|

2,873,083

|

79,815

|

2.7%

|

| Salt Lake City, UT |

692,741

|

674,849

|

17,892

|

2.6%

|

| Grand Rapids-Wyoming, MI |

402,848

|

393,138

|

9,709

|

2.4%

|

| Omaha-Council Bluffs, NE-IA |

501,309

|

518,223

|

12,078

|

2.4%

|

| Raleigh-Cary, NC |

563,555

|

551,457

|

12,098

|

2.1%

|

| Detroit-Warren-Livonia, MI |

1,902,208

|

1,861,948

|

40,260

|

2.1%

|

| Charleston-North Charleston-Summerville, SC |

323,937

|

317,316

|

6,621

|

2.0%

|

| Oklahoma City, OK |

649,469

|

636,476

|

12,992

|

2.0%

|

| Knoxville, TN |

363,742

|

356,712

|

7,030

|

1.9%

|

| Louisville/Jefferson County, KY-IN |

654,871

|

643,365

|

11,506

|

1.8%

|

| McAllen-Edinburg-Mission, TX |

268,924

|

264,231

|

4,693

|

1.7%

|

| Phoenix-Mesa-Glendale, AZ |

1,916,060

|

1,883,203

|

32,857

|

1.7%

|

| Seattle-Tacoma-Bellevue, WA |

1,929,525

|

1,897,882

|

31,643

|

1.6%

|

| Stockton, CA |

236,202

|

232,430

|

3,773

|

1.6%

|

| Columbus, OH |

998,599

|

984,248

|

14,351

|

1.4%

|

| Dallas-Fort Worth-Arlington, TX |

3,263,838

|

3,219,303

|

44,535

|

1.4%

|

| El Paso, TX |

336,649

|

332,206

|

4,443

|

1.3%

|

| San Francisco-Oakland-Fremont, CA |

2,252,514

|

2,224,520

|

27,993

|

1.2%

|

| Nashville-Davidson–Murfreesboro–Franklin, TN |

853,134

|

843,884

|

9,250

|

1.1%

|

| Charlotte-Gastonia-Rock Hill, NC-SC |

909,444

|

899,769

|

9,675

|

1.1%

|

| Denver-Aurora-Broomfield, CO |

1,367,534

|

1,354,042

|

13,492

|

1.0%

|

| Boise City-Nampa, ID |

294,333

|

291,569

|

2,764

|

0.9%

|

| Portland-Vancouver-Hillsboro, OR-WA |

1,140,720

|

1,130,624

|

10,096

|

0.9%

|

| San Antonio-New Braunfels, TX |

990,899

|

982,408

|

8,491

|

0.9%

|

| Ogden-Clearfield, UT |

218,356

|

216,733

|

1,624

|

0.7%

|

| Rochester, NY |

535,248

|

531,540

|

3,709

|

0.7%

|

| Fresno, CA |

379,331

|

377,181

|

2,151

|

0.6%

|

| Washington-Arlington-Alexandria, DC-VA-MD-WV |

3,289,069

|

3,271,193

|

17,876

|

0.5%

|

| San Diego-Carlsbad-San Marcos, CA |

1,538,488

|

1,530,699

|

7,789

|

0.5%

|

| Indianapolis-Carmel, IN |

942,512

|

938,843

|

3,669

|

0.4%

|

| Columbia, SC |

380,167

|

378,761

|

1,406

|

0.4%

|

| Atlanta-Sandy Springs-Marietta, GA |

2,463,751

|

2,455,059

|

8,691

|

0.4%

|

| Riverside-San Bernardino-Ontario, CA |

1,390,906

|

1,386,822

|

4,084

|

0.3%

|

| Chattanooga, TN-GA |

251,933

|

251,223

|

709

|

0.3%

|

| Minneapolis-St. Paul-Bloomington, MN-WI |

1,892,017

|

1,886,761

|

5,256

|

0.3%

|

| Tulsa, OK |

460,519

|

459,782

|

737

|

0.2%

|

| Des Moines-West Des Moines, IA |

354,286

|

353,772

|

514

|

0.1%

|

| Cincinnati-Middletown, OH-KY-IN |

1,066,016

|

1,064,816

|

1,201

|

0.1%

|

| Honolulu, HI |

541,273

|

540,736

|

537

|

0.1%

|

| Allentown-Bethlehem-Easton, PA-NJ |

364,683

|

364,345

|

338

|

0.1%

|

| Greensboro-High Point, NC |

370,755

|

370,532

|

223

|

0.1%

|

| Cape Coral-Fort Myers, FL |

219,651

|

219,550

|

101

|

0.0%

|

| New York-Northern New Jersey-Long Island, NY-NJ-PA |

9,111,820

|

9,109,799

|

2,021

|

0.0%

|

| Baton Rouge, LA |

403,099

|

403,086

|

12

|

0.0%

|

| Miami-Fort Lauderdale-Pompano Beach, FL |

2,468,634

|

2,468,912

|

(279)

|

0.0%

|

| Worcester, MA |

353,710

|

353,834

|

(124)

|

0.0%

|

| Richmond, VA |

657,018

|

657,325

|

(306)

|

0.0%

|

| Albany-Schenectady-Troy, NY |

459,754

|

460,069

|

(316)

|

-0.1%

|

| Tampa-St. Petersburg-Clearwater, FL |

1,218,515

|

1,219,507

|

(992)

|

-0.1%

|

| Jackson, MS |

267,877

|

295,684

|

(427)

|

-0.2%

|

| Los Angeles-Long Beach-Santa Ana, CA |

6,143,325

|

6,154,926

|

(11,601)

|

-0.2%

|

| Baltimore-Towson, MD |

1,400,446

|

1,403,859

|

(3,413)

|

-0.2%

|

| Orlando-Kissimmee-Sanford, FL |

1,071,935

|

1,074,559

|

(2,624)

|

-0.2%

|

| Pittsburgh, PA |

1,214,245

|

1,218,032

|

(3,786)

|

-0.3%

|

| Dayton, OH |

402,031

|

403,437

|

(1,406)

|

-0.3%

|

| Boston-Cambridge-Quincy, MA-NH |

2,665,828

|

2,678,362

|

(12,534)

|

-0.5%

|

| Akron, OH |

341,435

|

343,042

|

(1,607)

|

-0.5%

|

| Scranton–Wilkes-Barre, PA |

272,047

|

273,574

|

(1,527)

|

-0.6%

|

| Greenville-Mauldin-Easley, SC |

315,824

|

317,638

|

(1,814)

|

-0.6%

|

| Colorado Springs, CO |

316,090

|

318,171

|

(2,081)

|

-0.7%

|

| New Orleans-Metairie-Kenner, LA |

582,177

|

586,123

|

(3,946)

|

-0.7%

|

| Chicago-Joliet-Naperville, IL-IN-WI |

4,549,732

|

4,582,384

|

(32,652)

|

-0.7%

|

| Youngstown-Warren-Boardman, OH-PA |

240,559

|

242,321

|

(1,762)

|

-0.7%

|

| Toledo, OH |

317,987

|

320,534

|

(2,548)

|

-0.8%

|

| Lancaster, PA |

252,253

|

254,288

|

(2,034)

|

-0.8%

|

| Buffalo-Niagara Falls, NY |

562,953

|

567,694

|

(4,741)

|

-0.8%

|

| Memphis, TN-MS-AR |

653,464

|

659,019

|

(5,555)

|

-0.9%

|

| Virginia Beach-Norfolk-Newport News, VA-NC |

867,917

|

875,329

|

(7,412)

|

-0.9%

|

| Jacksonville, FL |

634,680

|

640,178

|

(5,498)

|

-0.9%

|

| Springfield, MA |

322,963

|

325,801

|

(2,838)

|

-0.9%

|

| Hartford-West Hartford-East Hartford, CT |

651,931

|

658,182

|

(6,251)

|

-1.0%

|

| Syracuse, NY |

324,948

|

328,190

|

(3,242)

|

-1.0%

|

| Oxnard-Thousand Oaks-Ventura, CA |

348,124

|

351,742

|

(3,618)

|

-1.0%

|

| Bridgeport-Stamford-Norwalk, CT |

458,643

|

463,816

|

(5,174)

|

-1.1%

|

| Wichita, KS |

312,394

|

315,968

|

(3,575)

|

-1.1%

|

| North Port-Bradenton-Sarasota, FL |

265,715

|

268,786

|

(3,071)

|

-1.2%

|

| Kansas City, MO-KS |

1,053,613

|

1,066,414

|

(12,802)

|

-1.2%

|

| Tucson, AZ |

401,113

|

406,033

|

(4,920)

|

-1.2%

|

| Sacramento–Arden-Arcade–Roseville, CA |

957,779

|

969,534

|

(11,755)

|

-1.2%

|

| Poughkeepsie-Newburgh-Middletown, NY |

271,783

|

275,231

|

(3,447)

|

-1.3%

|

| New Haven-Milford, CT |

394,666

|

400,055

|

(5,390)

|

-1.4%

|

| Madison, WI |

361,542

|

366,488

|

(4,946)

|

-1.4%

|

| Las Vegas-Paradise, NV |

883,649

|

896,729

|

(13,081)

|

-1.5%

|

| Cleveland-Elyria-Mentor, OH |

1,056,167

|

1,075,588

|

(19,421)

|

-1.8%

|

| Harrisburg-Carlisle, PA |

334,668

|

341,123

|

(6,454)

|

-1.9%

|

| Philadelphia-Camden-Wilmington, PA-NJ-DE-MD |

2,866,722

|

2,922,956

|

(56,235)

|

-2.0%

|

| St. Louis, MO-IL |

1,391,853

|

1,419,265

|

(27,412)

|

-2.0%

|

| Birmingham-Hoover, AL |

520,572

|

531,024

|

(10,452)

|

-2.0%

|

| Little Rock-North Little Rock-Conway, AR |

362,670

|

370,444

|

(7,774)

|

-2.1%

|

| Providence-New Bedford-Fall River, RI-MA |

722,008

|

738,127

|

(16,119)

|

-2.2%

|

| Milwaukee-Waukesha-West Allis, WI |

849,075

|

868,393

|

(19,318)

|

-2.3%

|

| Modesto, CA |

180,419

|

184,600

|

(4,181)

|

-2.3%

|

| Lakeland-Winter Haven, FL |

210,233

|

215,306

|

(5,073)

|

-2.4%

|

| Palm Bay-Melbourne-Titusville, FL |

207,642

|

214,568

|

(6,926)

|

-3.3%

|

| Albuquerque, NM |

399,997

|

413,688

|

(13,691)

|

-3.4%

|

| Augusta-Richmond County, GA-SC |

232,695

|

241,661

|

(8,966)

|

-3.9%

|

The data and analysis for this post comes from Analyst, EMSI’s web-based labor market data and analysis tool. For more information, email Josh Wright. Follow us on Twitter @DesktopEcon.

Austin skyline image by Bigstock.