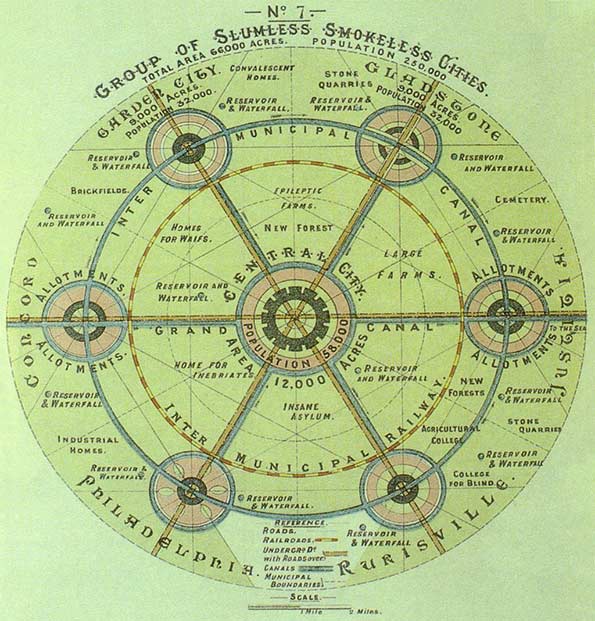

Every few years the ideals of Ebenezer Howard’s garden city utopia are resurrected in an attempt by the UK government to create new communities, and address the country’s housing crisis. Sometimes this takes the form of new towns or eco-towns, and sometimes proposals for an actual garden city are put forward – as in the last budget.

Rather than just rolling out this romantic terminology, we should take a closer look at garden city ideals and how they can be adopted to make the proposed Ebbsfleet development a success.

Several years ago my colleague Michael Edwards presciently forecast the current problems in the Thames Gateway where Ebbsfleet falls, with a dominance of private development that does little to provide for local employment and walkable communities.

Ebenezer Howard’s utopian vision

He outlined the need to return to funding principles similar to the garden city model, where development trusts retain freeholds on the land. This model, based on investment in infrastructure and services, is a fundamental principle that shifts from short-term returns to a long-term relationship created between the collective or public landowner and local inhabitants.

Lessons From History

Despite the fact that the garden city was a highly influential model throughout the first half of the 20th century, ultimately leading to the establishment of some key settlements in the UK, US and elsewhere in the world, it has had few genuine successes. After World War II, similar utopian dreams of creating model communities, with decent housing surrounding a well-designed centre, met with the reality. British reformer William Beveridge famously summed them up for having “no gardens, few roads, no shops and a sea of mud”.

You’d be forgiven for thinking that past lessons would be applied to the next generation of housing. But, even the post-war housing plans – though inspired by the garden city movement of the interwar periods – failed to plan the new housing in relation to transport, employment and public services such as shops and schools. While UK government reports have tried to draw lessons from both their positive and negative aspects, they have also been criticised in more recent reports, for lacking a sense of community – although it should also be said that “community” takes time to develop and cannot be “designed” as such.

Many of the challenges of creating new communities are bound up in the spatial separation between newcomers and older inhabitants, a lack of social infrastructure, such as doctor’s surgeries and schools, and difficulties that stem from long commutes, such as lower net income and the strain this has on families. Ruth Durant found this in her 1939 study of Burnt Oak on the outskirts of London.

Early post-war new towns were similarly criticised for their very slow build-up of health services, higher schooling, cultural facilities and decent shopping facilities, although some did better with the provision of local employment, due to many people moving to the towns with a local job linked to their housing. With shifts in the industrial economy, such beneficial connections between home and work (one of the tenets of the garden city) reduced over time.

Modern Twist

The challenges today are slightly different, however. People live more mobile and fragmented lives and are arguably less likely to be tied to place as was the case for the primarily working-class (and manual labouring) communities of the past. This poses the risk that community will be lost because of how transient people can be.

But increased mobility and social interaction don’t have to be mutually exclusive. Indeed, a lack of mobility is the worst problem that can be imposed on a community: both work and leisure must be accessible to people. Plus, with the advent of the internet and grass-roots activism, connections can traverse space more easily. This has allowed movements such as the Transition Network, which brings communities together around sustainable issues, to blossom.

Adapting to Change

UCL’s EPSRC funded Adaptable Suburbs project has studied the evolution of London’s outer suburban towns over the past 150 years, providing some clues on what has made for the relative success of the original garden cities over other planned settlements. It is clear that their success has been dependent on excellent transport connections, coupled with the provision of local employment and access to employment at a commutable distance.

Also important is the provision of a mixed-use town centre, giving a destination for a wide variety of activities in addition to retail: community activities, schools, leisure and cultural uses. Centres work well when connected to the street network, accessible by foot, bicycle, public and private transport. This multi-functional design has helped even the smallest of centres to sustain themselves through the most recent economic recession.

A recent government report, “Understanding High Street Performance”, also found that successful town centres are “characterised by considerable diversity and complexity, in terms of scale, geography and catchment, function and form … [as] a result, the way in which they are affected by and respond to change is diverse and varied”.

It is almost impossible to predict how society will change in the future, particularly as new technologies have the power to change how people connect and build community. But what is evident is that here lies another essential aspect of building successful communities: in allowing for places to adapt to change.

This needs to be a foundational aspect of the government’s new cities – simply invoking the phrase “garden city” is not enough. By building places with sufficient flexibility of buildings, infrastructure and uses, coupled with links that allow for local and wider-scale trips to take place, with the necessary long-term financial investment, we can start to create places that will successfully weather the future.

This article was originally published on The Conversation.

Dr Laura Vaughan is Professor of Urban Form and Society at the Bartlett, University College London. She has been researching poverty and prosperity in cities, suburbs and the space between them for the past dozen years using space syntax – a mathematical method for modelling social and economic outcomes. Her edited book ‘Suburban Urbanities’ is due to come out in UCL Press in 2015.