This piece originally appeared at Macrobusiness.

The United Kingdom (UK) housing system is arguably the worst in the world because of a myriad of policies that work to severely restrict supply, pump demand, and make renting a highly undesirable substitute for home ownership. These policies have led to the UK housing market experiencing:

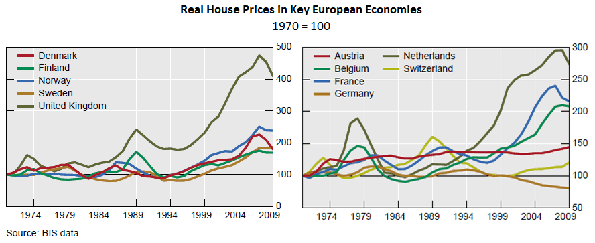

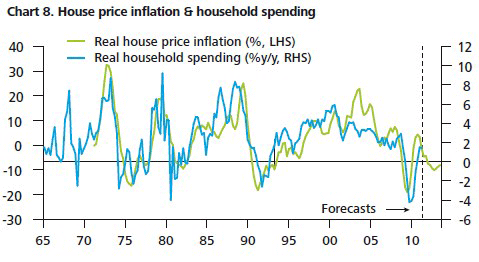

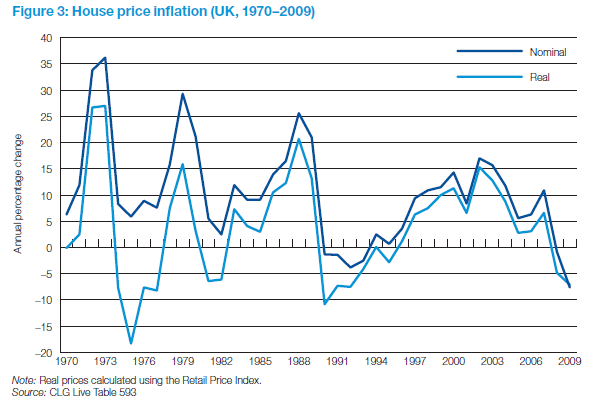

1) a higher level of house price inflation than most other European nations:

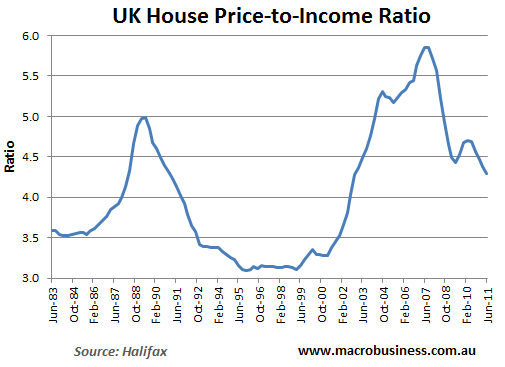

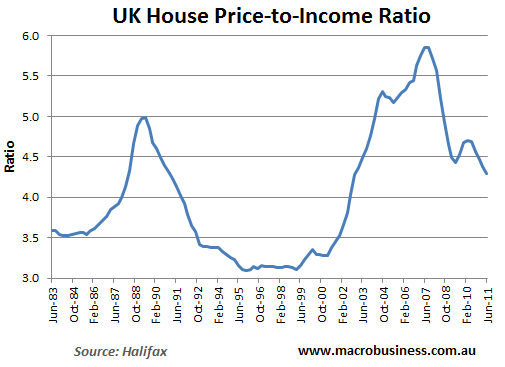

2) Relatively expensive housing on a price-to-earnings basis:

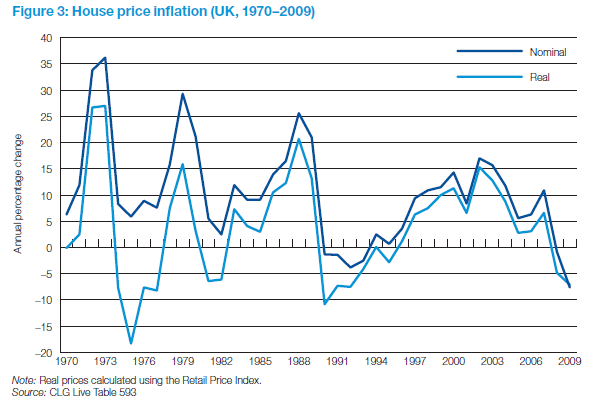

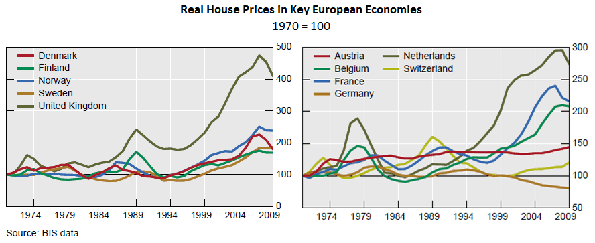

3) Extreme house price volatility:

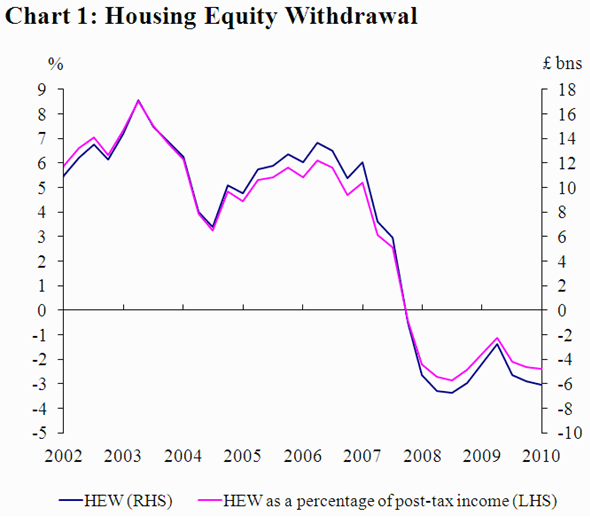

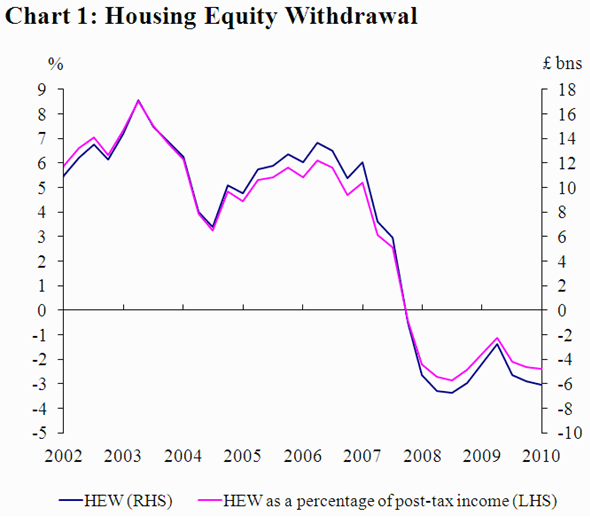

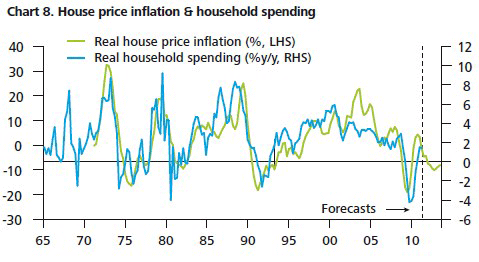

4) Which has also increased the volatility of the economic cycle due to the positive effects on consumer spending of equity withdrawals from rising home values and heightened austerity in the bust phase:

At the core of the UK’s housing problems is the straightjacket that was placed on housing supply following the passage of the Town and Country Planning Act in 1947, which nationalised development rights. Essentially, the pre-existing right of landowners to build-on or re-develop their land was removed and handed to the state, thereby requiring land owners to seek planning permission before anything other than minor renovation work was undertaken.

UK housing supply effectively became a centrally planned system whereby government bureacrats would attempt to predict some years ahead the required numbers of dwellings that ought to be built in an area to meet demand. However, as explained brilliantly in a detailed paper by the Policy Exchange, the key outcome from the UK planning system has been a housing market that has delivered some of the oldest, smallest and most expensive homes in Europe of a type that are least preferred by households. Put simply, UK households are paying more for housing than their European counterparts and receiving less in return:

Central planning attempts to ensure that what is thought best for the people by the central planners is what is produced. So, as we showed earlier, the system currently attempts to produce exactly the number of dwellings which are estimated to be required from calculations of need, calculations involving assessments of demographic change, household formation, household splits, migration, deaths, births, etc. Built into the system is a pressure at all levels to provide the minimum. Using green field sites is politically problematic. The cry goes up that the countryside is being buried under tarmac. And anyway, as we have shown, the system adjusts. If too little housing is provided, house prices rise and housing becomes expensive. When it is more expensive, people can afford less and so buy smaller homes. With smaller homes, more dwellings can be provided on less land because homes can be built at higher densities, namely flats or houses with tiny gardens.

But is this really what people want? In March 2005, a widely reported survey carried out by MORI on behalf of the Commission for Architecture and the Built Environment found that over 50 per cent of those questioned wanted a detached house and 22 per cent preferred a bungalow. Only 2 per cent per cent expressed a preference for a low rise flat and less than 1 per cent a flat in a high rise block. But since detached houses and bungalows use more land than other kinds of house, fewer and fewer are built each year. And many are also demolished to make way for terraced houses or blocks of flats. So while as recently as 1990 only about an eighth of newly built dwellings were apartments, by 2004 the proportion had increased to just under a half…

So whilst people may not want to live in them or want them built where they live,more and more blocks of flats of just this type are being built because the central planners think that they should have them, and because the production norms are filled more easily in this way than by building houses or bungalows…

The British planning system means that the most important thing the developer has to do is to obtain planning permission. Once this has been obtained, given the demand for housing, whatever is built can be sold. So the way to make the greatest profit, having obtained permission, is to produce the permitted dwellings at the lowest possible cost. Adding good design is an unnecessary expense because whatever is built will sell. So the constraints imposed by the planning system work against the achievement of a better architectural environment, something which might be achieved with less pressure to build at the lowest possible cost. Competition between developers on design becomes largely unnecessary because they know that they will be able to sell whatever they produce.

So the current position is that what people want, when asked, is lower density housing. What they get, what the planning system now insists upon, is high density development, much of it in the least desired form – blocks of flats…

British housing tends to be older than elsewhere in Western Europe. Because they are older their efficiency, in terms of heating for example, tends to be less. The houses [also] tend to be smaller… New houses tend to be even smaller on average than existing houses. In addition, house prices rise faster in the UK so that, year on year, housing in Britain has been getting more expensive relative to that in the rest Europe…

If fifty years of planning has achieved one thing… Britain [now] has the oldest, pokiest, housing in Europe.

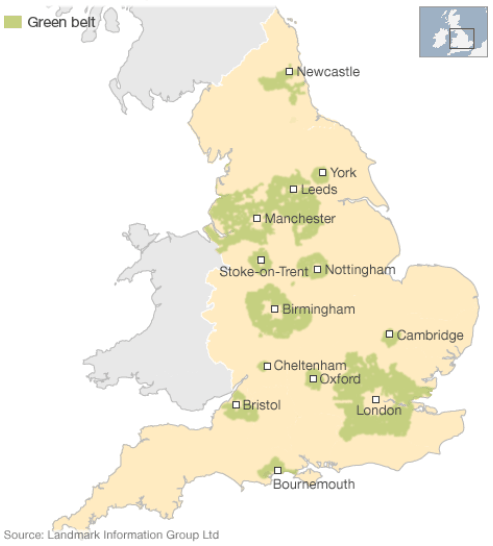

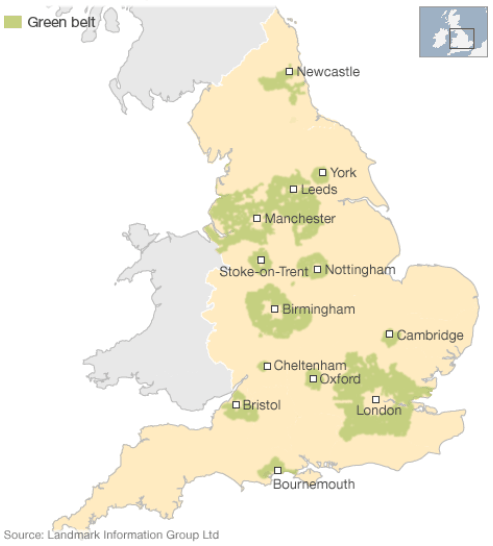

Compounding the above regulatory constraints on land/housing supply are the greenbelts that have been errected around all of the UK’s major housing markets, which have excluded large swathes of agricultural land from urban development and helped to push-up land prices. A map of the UK’s greenbelts is provided below:

In addition, the overriding planning objective in the UK has increasingly become one of ‘urban containment and ‘densification’. In the 1990s, the Central Government explicitly required that 60% of all new land for housing must be brownfield land – i.e. land which has already been developed for some other purpose.

This 60% in-fill requirement necessarily meant the restriction of land supply and higher land prices. It has also produced some perverse outcomes owing to the fact that many brownfield sites that come onto the market for redevelopment are not necessarily located where there is demand for housing. Key amongst these perverse outcomes are the construction of high density developments in poorly located areas as well as ‘leapfrog’ developments far away from the existing urban fringe:

In southern England, where demand is great, the brown fields norm is complied with by constructing high-density developments whenever and wherever the land has become available, whether centrally, in the inner suburbs, in the outer suburbs, or in the middle of the country miles away from public transport. So the site of a house or hotel in the middle of the London Green Belt may be redeveloped to provide more houses or a larger hotel. The development is on a brown field site so that fulfils the production norm, to be sure. But the development neither preserves the countryside, nor does it reduce the use of private transport. Indeed, it actually increases it above what might have been achieved on a green field site bordering the town.

A final related roadblock to housing supply in the UK is its centralised fiscal system, whereby local authorities – which are the primary decision makers on development and have statutory obligations to provide services for new houses – receive very little revenue from increased population and housing. As such, these local authorities tend to be biased against development.

Combined, these regulatory constraints on new housing construction have meant that housing supply in the UK has been incapable of responding quickly and efficiently to changes in demand, thus placing upward pressure on prices and creating expectations of future capital growth.

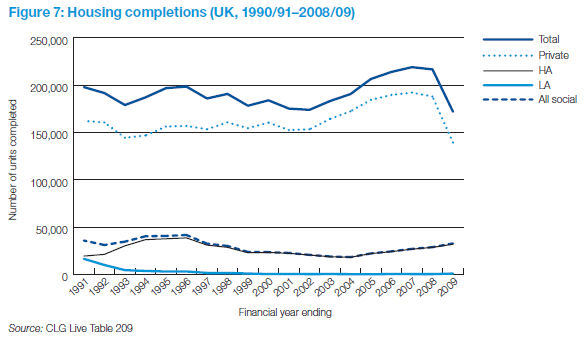

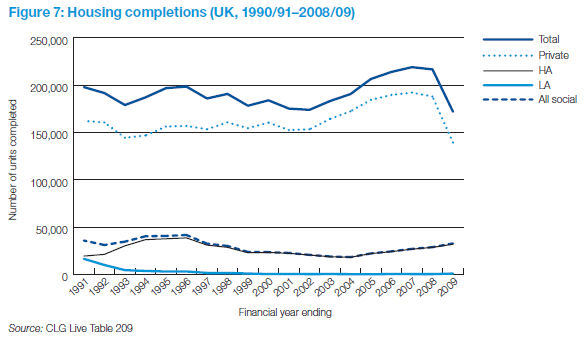

According to the Joseph Rowntree Foundation’s (JRF) Housing Market Taskforce report on reducing volatility in the UK housing market, only an average of around 180,000 homes per annum were completed in the UK over the past two decades – only slightly above construction volumes in Australia, despite the UK having nearly triple the population (around 62 million).

And as shown below, despite the massive run-up in prices between 2000 and 2007, there was only a minimal supply response towards the end of the latest housing bubble, confirming that UK housing supply is highly unresponsive (‘inelastic’) to changes in demand.

More worryingly still, new home construction has reportedly fallen to its lowest level since the 1920s, with just 105,000 new homes completed in 2010.

The supply constraints present in the UK housing market ensured that the extra demand arising from the UK’s deregulated mortgage market – where lenders were offering 100% plus LVR (i.e. no deposit) mortgages to first-time buyers at the height of the most recent housing bubble – manifested into escalating prices rather than new home construction. By contrast, in the wake of the global financial crisis, UK lenders rationed credit and demanded higher deposits (reduced LVRs), which contributed to the falling prices.

In a similar vein, the UK’s deregulated rental market and lack of security of tenure (whereby six month leases are the norm) has ensured that renting is a second rate option, thereby encouraging residents to strive (and borrow big) for owner occupancy. With this extra demand for owner-occupied housing not met by increased supply, the inevitable result has been ’panic buying’ from first-time buyers when house prices are rising and the opposite when prices are expected to stagnate or fall.

Change in the air?

The concerns about the UK housing situation appear to have come to a head, with the Central Government moving to reform the planning system by:

- streamlining the development process by reducing more than 1,000 pages of regulations and red tape to just 52 pages; and

- implementing a “presumption in favour of sustainable development”, which has the potential to open up the greenbelts to new housing development.

The UK Prime Minister, David Cameron, has described the planning system as “slow and bureaucratic” and argues that reform is essential. He also laments the fact that the average first-time buyer without parental help in the UK is 37 years of age.

However, conservationists and NIMBY groups have rallied against the changes arguing that the reforms risk concreting over the UK’s precious country side and robbing the nation of productive farmland – a ridiculous claim when you consider that:

- only around 8% of UK land is urbanised, which is lower than the Netherlands (15%), Belgium (15%), Germany (13%), and Denmark (9%); and

- the proportion of UK land used for agriculture is among the highest in the old European Economic Community: 78% compared with an average of 64%.

According to Dr Oliver Marc Hartwich, an economist and planning expert at Sydney’s Centre for Independent Studies, concerns that the UK will concrete over the country side if the proposed planning reforms are implemented are misguided:

Dr Oliver Hartwich, an economist with the Centre for Independent Studies, who has studied the British system, believes that without the postwar planning system, the UK would only “look slightly different, but not much”.

Instead, he suggests the real impact of the green belt has been to fuel house price inflation and push development further into the “real” countryside beyond the green belt, leading to more commuting, fuel use and stress.

“No-one wants to concrete over the countryside,” he adds. But British cities are overcrowded.

“What this sort of planning does is encourage a system where bubbles are likely. The idea that you need to get into the property market in your early 20s is very harmful but it’s something that this planning system promotes.”

Dr Hartwich is particularly well placed to comment on the UK planning system given that he was born and educated in Germany – a country regarded as having one of the best planning systems in the world – before residing in England in the 2000s. He has also written detailed studies of planning systems from around the world (for example, see Why Some Countries Plan Better than others).

Whether the UK Central Government will ultimately succeed in reforming the UK planning system remains to be seen. Nevertheless, it is heartening to see it taking on vested interests and fighting the good fight.

Photograph: New, smaller exurban housing in the London area (by Wendell Cox).

Leith van Onselen writes daily as the Unconventional Economist at MacroBusiness Australia. He has held positions at the Australian Treasury, Victorian Treasury and currently works at a leading financial services company. Follow him @leithVO.