Justin Chapman contributed research and editorial assistance to this piece. This essay is part of a new report from the Center for Opportunity Urbanism called “America’s Housing Crisis.” The report contains several essays about the future of housing from various perspectives. Follow this link to download the full report (pdf).

If the United States could remove current obstacles holding back members of the Millennial Generation from owning homes, the value of the housing market would increase by at least one trillion dollars over the next five years. Policies that would eliminate or sharply reduce financial obstacles that are currently hindering thirty somethings who want to start raising a family in the suburbs from buying a home would enable the construction and sale of as many as five million more homes between now and 2020. Residential investment represents about five percent of the country’s GDP, not counting the ancillary spending that results from such purchase. So any sound housing policy for the United States should begin and end with programs that allow these “missing Millennials” to join the ranks of America’s home owners.

HOW WE ARE FAILING THE NEXT GENERATION… AND OURSELVES

The Millennial Generation (born 1982–2003), is made up of about 95 million Americans, most of whom are now in their twenties or thirties. They have been raised to think of life as a series of hurdles to be jumped with each obstacle becoming increasingly more difficult to overcome. Part of this mentality stems from the sheer size of the generation, which created enormous peer competition for success in school. Another source of this pressure to achieve came from their parents, who constantly

emphasized the importance of going to college, doing extracurricular work in high school to improve the chances of being selected to attend the college of their choice, and spending time studying, not working, to make sure their grades were good enough. This kitchen table conversation was at least partially generated by the pressure that an increasingly global economy put on family incomes as they were growing up, with particular urgency after the Great Recession.

Despite the investment in education the generation has made in response to these pressures, the question remains as to whether or not Millennials will be able to fully participate in the experience of home ownership. The answer to this question will be determined both by the efforts of Millennials and also to the degree that efforts to lower the height of the hurdles in front of them are successful.

There are some people, such as Brookings Institute researcher Matthew Chingos, who don’t believe the hurdles are unique to this generation. He has suggested, for instance, that student debt loads weren’t high enough to really impact the housing market.iv, John McManus, an award-winning editorial and digital content director for Builder magazine, suggested any delays in home ownership were due primarily to the inherent desire to wait before making decisions in the hope something better will turn up.vi Despite evidence

of mounting student debt, declines in workforce participation, and stagnant wages, these economists believe the housing issue can solve itself within the context of existing policies and current economic growth rates.

Yet from the perspective of most young Millennials these hurdles are both very real and huge indeed. Not addressing them will impact their lives—and the nation’s economy—for decades to come.

LOVE AND MARRIAGE: MILLENNIAL STYLE

From 1920 to 1940, when members of the GI Generation were about the age that Millennials are today, the median age for a first marriage was 24.4 for males and 21.3 for females, numbers that remained fairly constant until the 1980s. In the 1990s, the median age for first marriages by Generation X males rose to 26.5 and 24.5 for females.

The early marriage age in the 50s and 60s sparked a rapid growth in suburbs; the percentage of Americans living there doubled after World War II. By 1970, 38 percent of Americans lived in the suburbs and, by 1980, 45 percent did, triple the rate of suburban home ownership than before WWII. As of 2012, nearly 75 percent of metropolitan area residents live in suburban areas. Overall, 44 million Americans live in the core cities of America’s 51 major metropolitan areas; more than half of them live in areas that are functionally suburban or exurban with low density and high automobile use. Meanwhile, nearly 122 million Americans live in the suburbs.

Will Millennials reverse this pattern? Clearly they are marrying even later: the average age of first marriage in the United States as of 2011 was 28.7 for men and 26.5 for women. This trend has caused more to linger longer in cities and postpone home ownership until much later in their lives. Furthermore, in line with their more urban existence,

the fertility rate has fallen from the replacement rate of 2.1 for Generation X to 1.9 for Millennials.

But this doesn’t mean Millennials aren’t interested in starting a family later in life.

A Pew Research Center report found that among those who have never married and have no children, 66 percent wanted to marry and 73 percent wanted to have children. Although they may be late to the family party, the large size of the Millennial Generation, almost double that of Xers, means there are still plenty of families being formed, just not at the rate that historical precedents suggested would happen. In fact, the absolute number of household formations rose to their highest level in a decade in 2014. The trend continued in 2015 as more and more Millennials entered the prime age for getting married.

These Millennial trends in marriage and parenting can be explained, in part, by the impact of the Great Recession and more than a decade of stagnant wages. But they are also due to “cultural changes over time… including more women in the workplace, the increased amount of higher education among members of the generation, particularly females, and greater social acceptance of premarital sex, birth control, and cohabitation before marriage,” according to Christine Elliott and Williams Reynolds III of Deloitte University Press.xv For example, one of the reasons members of the Silent Generation got married so young in the 1960s was so they could have socially acceptable sex. No such incentives exist for members of the Millennial Generation.

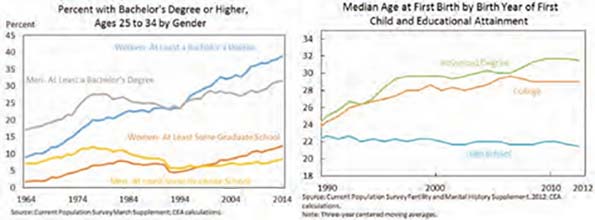

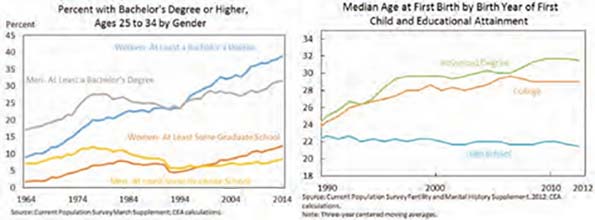

Liberated from the straight jacket of gender determined roles in society, female Millennials now outnumber men in every type of higher educational pursuit. Almost 40 percent of female Millennials aged 25–34 have a bachelor’s degree and about half of them are married, a greater percentage than among any other educational attainment cohort. Whereas few if any female 25–34 year olds had attended graduate school in 1964, 13 percent of Millennial females of that age have reached that milestone today. All of these gains outpace college educational gains among males in the same time period.

Source:www.whitehouse.gov/sites/default/files/docs/millennials_report.pdf

Millennial women who are not as well educatedxvi and do not have any economic stake in pursuing a career have their first babies, on average, at age 19 or 20. Well-educated moms have their first child around 28 or 29, usually after they have saved some money from their participation in the workforce. The delay in childbearing is greatest among those women with graduate degrees. Their average age for having their first child is now over 31, a full decade longer than their counterparts with only a high school degree. This represents a remarkable reversal of earlier trends over the last 25 years when more educated women were more likely to have children earlier than their less well-educated peers. In all likelihood, this phenomenon represents another kitchen table conversation about family finances with more educated females having more to lose by stepping out of the workforce and their preferred career track by having a baby than their less educated counterparts.

In a sense, the cultural changes that society has witnessed, driven by a new set of Millennial beliefs and values about the role of women in society, has run up against the realities of today’s economy. The best solution to overcoming this obstacle would be a growing economy with wages increasing comparable to what transpired in the 1990s. Expanded parental leave policies from companies such as Facebook and Netflix introduced for both their male and female employees might also impact this trend, or at least the timing of starting a family. Other solutions designed to artificially increase wages or provide tax incentives are much less likely to overcome the strong cultural trends impacting family formation that are embedded within the Millennial psyche.

MILLENNIALS WANT A PIECE OF THE AMERICAN DREAM, IF ONLY THEY COULD AFFORD IT

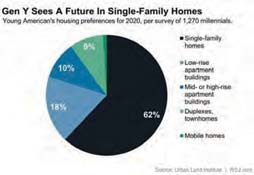

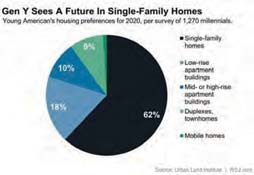

Not only when they marry but also where these new families choose to reside will have an enormous impact on American living patterns for decades to come. Despite what some of have written about Millennials being a “sharing generation” averse to owning things, the generation’s actual attitudes or aspirations toward home ownership are remarkably similar to those of previous generations. An Urban Land Institute study, conducted at the end of 2014 of Americans between 19 and 36 years of age, found that Millennials remained determined to eventually own their home, with 70 percent of them planning to do so by 2020. “The Great Recession has not dimmed the generation’s preference for single-family homes, mostly detached,” wrote Leanne Lachman, the survey’s co-author, a real estate consultant and a Columbia Business School executive in residence, in a report outlining the survey’s findings.

The same percentage of renters as home owners in the New York Federal Reserve’s Survey of Consumer Expectations in February 2014 thought home ownership was a good or very good investment. Almost 65% of millennials aged 21 to 34 looked at real estate websites and apps in August, and the market share of first time home buyers of existing homes increased to 32 percent from 28 percent in July of the same year. Realtor.com’s chief economist, Jonathan Smoke, found that 25–34 year olds were 70 percent more likely than the average adult to be looking for a home to buy on realtor.com. He estimated half of all home sales activity for the first half of 2015 could be attributed to first-time buyers and, according to the NAR 2015 Home Buyer and Seller Generational Trends report, Millennials comprised 68 percent of all such buyers.

“People who believe that Millennials are disinterested in home ownership are grossly mistaken,” said Smoke. “This generation hit the job market during one of the largest recessions of all time and

they’ve had to work hard to establish credit and save for a down payment.”

One solution for Millennial couples unable to qualify for a mortgage is, of course, to rent a course of action many young families just starting out in life have traditionally pursued. The New York Federal Reserve study found the number one reason renters gave for not buying a home was they didn’t have enough money saved for a down payment or had too much debt. A majority also reported that their incomes were too low to support the payments on a mortgage. These responses nicely summarize the economic barriers to Millennial home ownership. As a result, the typical first-time home buyer now rents for six years before buying, up from 2.6 years in the early 1970s, according to a new analysis by Zillow. The median first-time buyer is 33—in the upper range of the Millennial generation, which roughly spans ages 15 to 34. A generation ago, the median first-time buyer was about three years younger.

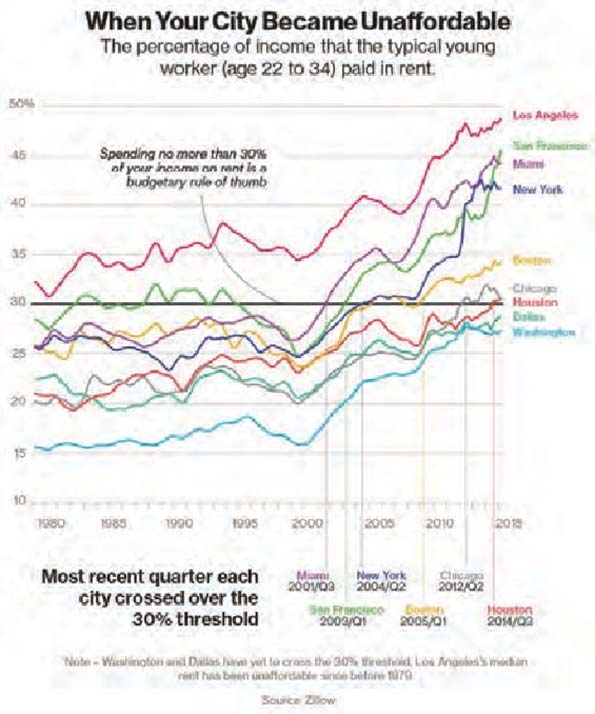

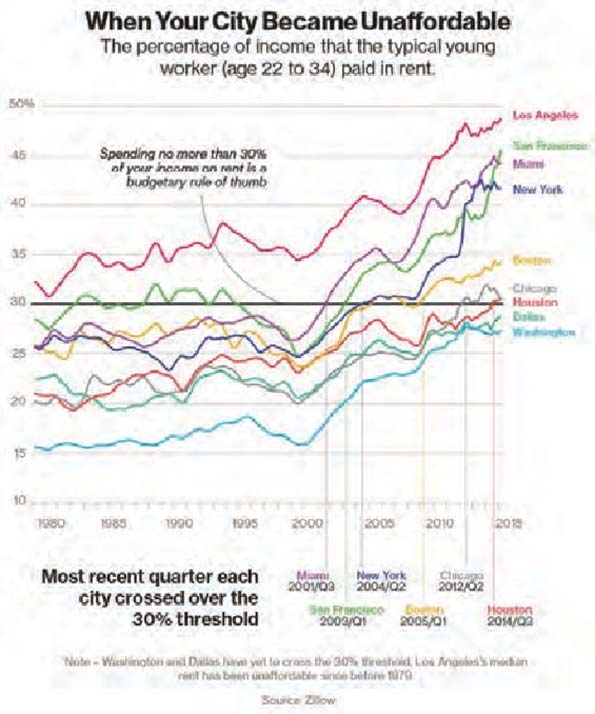

Ironically, many Millennials are being pushed into the home buying market by continuously rising rents that are making all forms of housing increasingly unaffordable. As Svenja Gudell pointed out, “We’re also finding that—given how much rental rates are currently rising—a lot of folks are having a hard time saving for a down payment and qualifying for a mortgage.” The oft violated rule of thumb says that families should not spend more than 30 percent of their budget on housing costs. But many young renters are paying more than that. “A striking 46 percent of renters ages 25 to 34—the core of the home buyer market among Millennials—spend more than 30 percent of their incomes on rent, up from 40 percent a decade earlier,” according to a report by Harvard University’s Joint Center of Housing Studies.

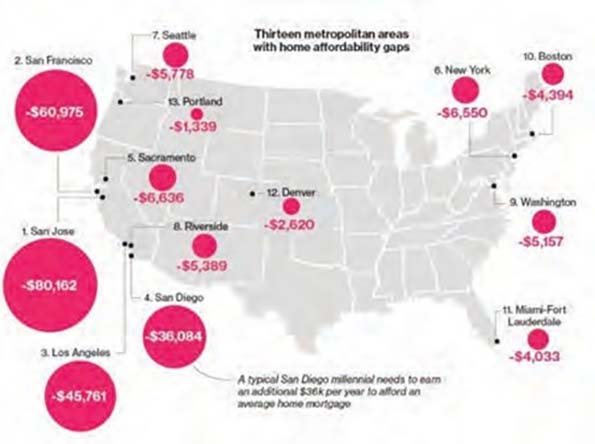

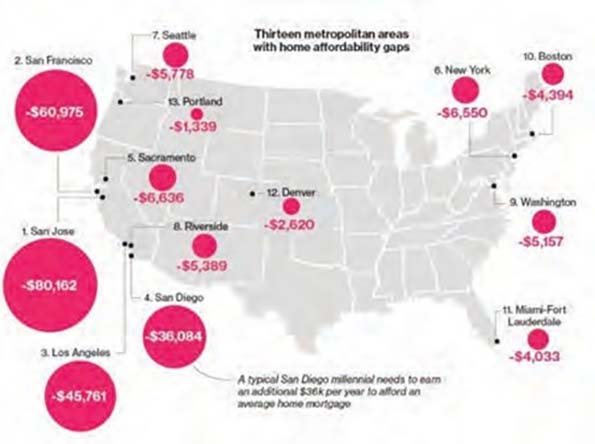

Along the coast, in cities such as San Francisco, Los Angeles, New York, or Miami, rental costs exceed 40 percent of Millennials’ median income, with many paying as much as half of their budget on rent. A minimum wage worker in Orange County, Southern California’s most desirable suburban environment, would have to work 110 hours per week or over 15 hours a day to afford a one bedroom apartment where he or she worked. Inland, in cities such as Dallas, Houston, Chicago, and D.C., Millennials are spending just about 30 percent of their median income on rent. And the situation continues to worsen.

More striking than these regional differences is the new relationship between the costs of renting versus owning a place to live. By the fourth quarter of 2014, the average mortgage cost was just 21 percent of average household income in the Dallas area, compared to an average of 28.5 percent of a family’s income being spent on rent. Across the country, it has become less costly on average for Millennials to own a home (21.4% of income) than to rent (30.1%).

MILLENNIALS TRYING TO BUY HOMES

For those who decide to take the plunge and buy a house, the tighter mortgage-qualification standards put in place after the Great Recession in reaction to the collapse of the financial markets when collateralized debt obligations (CDO) supposedly backed by sound mortgages turned out not to be worth the computer screens they popped up on present the first hurdle to their goal. To prevent such disasters in the future, Fannie Mae, whose reinsurance programs set the boundaries of risk that mortgage lenders will tolerate, prohibited certain types of mortgages altogether and emphasized a return to the traditional 20 percent down, thirty year term, fixed rate mortgages that had become the standard lending instrument when they were created to revive the nation’s housing market after the Great Depression.

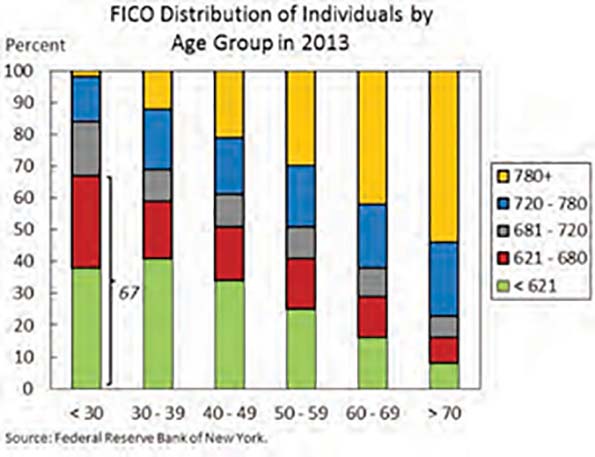

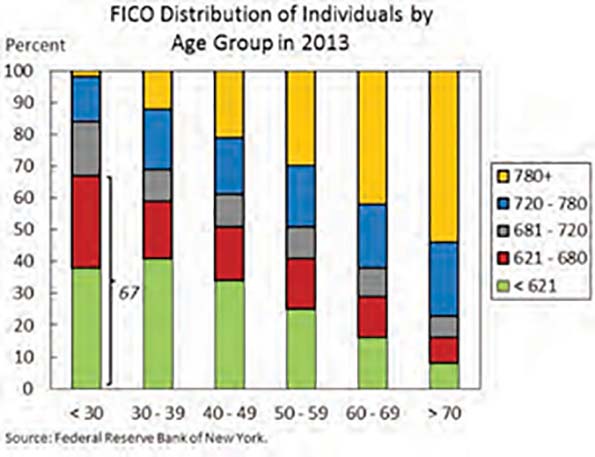

For a generation that has experienced falling wages and high levels of unemployment, this requirement can be seen as just too high a hurdle to even attempt to jump. Even if they can scrape up the money for the down payment, two-thirds of Millennials have a FICO score of under 680, limiting their ability to secure a government guaranteed mortgage and often saddling them with additional payments. Andrew Jennings, senior vice president and chief analytics officer at FICO said that “people in the 600 to 700 [credit score] range average have $25,000 in non-mortgage debt mostly from credit cards and student loans.” He pointed out that changes to the FICO score would make it easier for young adults with a thin credit history to qualify for a home loan. “One way to ease some households into ownership is to ease access to credit.”

Fannie Mae’s Community Home Buyer program takes a step in that direction by lowering the down payment requirement for qualified buyers to just 5 percent. North Carolina and New Hampshire have also introduced programs that lower down payment requirements to 3 percent in an attempt to woo Millennials into buying a home in their state.xxviii More of these programs should be enacted to knock down this particular hurdle facing Millennials.

(chart: https://www.whitehouse.gov/sites/default/files/ docs/millennials_report.pdf)

Much of their lack of credit worthiness stems from the lousy economic environment Millennials have experienced as they grew up.

Americans between 18 and 34 years of age are earning less today than the same age group did in the past. The average earning of a Millennial was $33,883 (in 2013 dollars) in the four years following the recession. This represented a drop in average wages of 9.3 percent in just a decade (after adjusting for inflation) and is the lowest average wage for this age group since 1980. According to Rob Shapiro, a noted economic policy analyst, annual income gains for thirty something households (headed by Boomers) averaged 2.6 percent under Reagan and 2.4 percent under Clinton. Similarly aged households headed by members of Generation X under George W. Bush experienced income losses averaging 0.3 percent per year, followed by even greater losses averaging 1.8 percent per year among the first wave of Millennials in Obama’s first term.

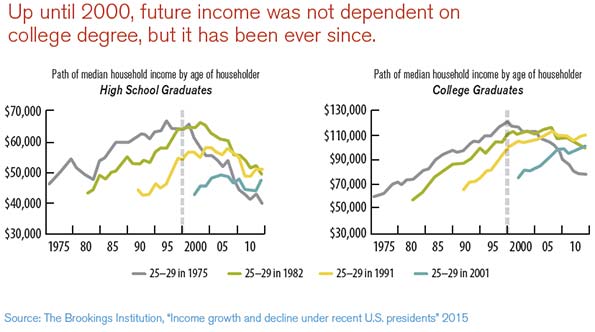

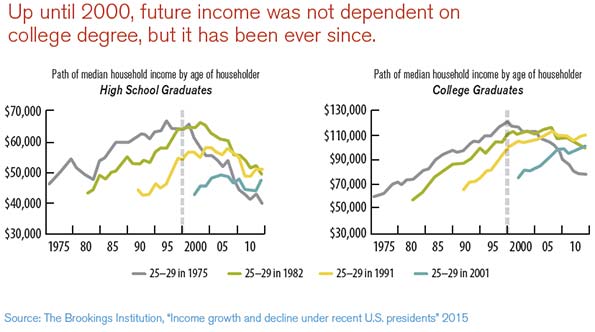

The situation is even worse for those with only a high school education. In a report written for the Brookings Institute in 2015, Shapiro showed that in the last century those with a high school education could expect their income to grow as they got older, even if it started from a lower base. This is no longer the case. In this century, those with only a high school education have actually experienced a drop in their earnings as they got older. Meanwhile, those with a college education not only start with an initially higher level of income, they can also expect to see their earnings grow in the course of their lives. College has become the ultimate hurdle in a Millennial’s life, with failure to get a degree becoming a life sentence of lower economic opportunity.

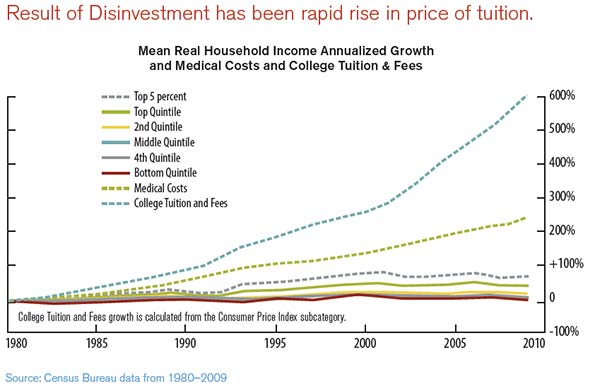

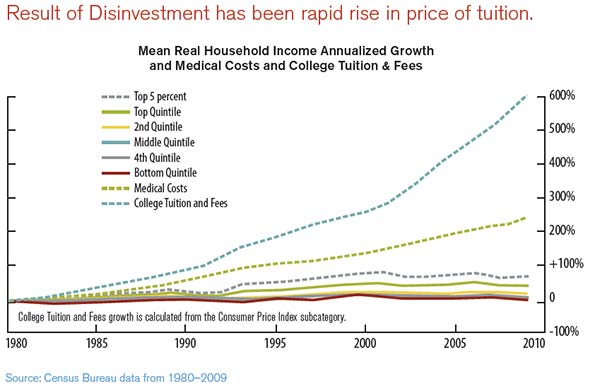

The part about going to college that most parents worry about is not so much whether or not their child will get in and graduate, but how in the world they or their children will be able to afford to pay for their tuition bills. From 1980 to 2010 the price of tuition skyrocketed by 600 percent. In the same period, health care inflation rose by just over 200 percent. Meanwhile incomes for all but the top 5 percent of earners remained basically flat.

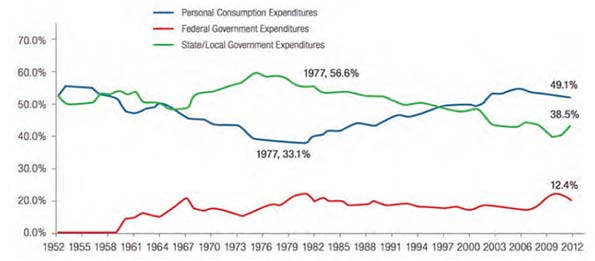

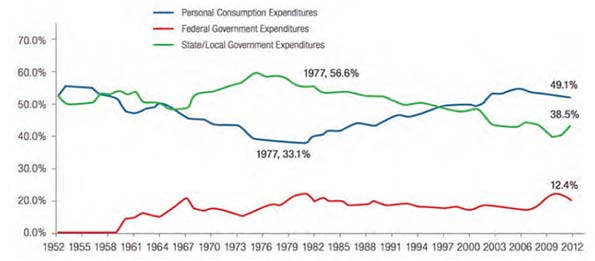

In many ways this crisis has been precipitated by the unwillingness or inability of government to absorb much of the burden for higher education. This follows a notion introduced by the Carnegie Commission in the 1970s that an educated workforce was not an investment that government alone should pay for, despite its proven benefits in expanding the middle class and the country’s economy. Most people agreed with the report’s argument that those who would benefit most directly from acquiring some sort of a degree—the student and their family—should pay an increasingly large share of its cost.

Coupled with the inability of states, particularly after the Great Recession, to subsidize the cost of college at historical levels, this policy led to families in 2014 shouldering the majority of the cost of sending their child to college for the first time in the nation’s history. Overall, the share of higher education costs paid for by students and families increased from 33 percent in 1977 to just under 50 percent in 2015.

Faced with the need to somehow pay for school, students and their families turned to student loans as the default solution. The result has been a disaster for them and for the American economy, particularly its housing industry.

Student loan debt doubled from 2007 to 2015. It now exceeds $1.2 trillion in the United States, more than the country has borrowed to pay for all the cars on the road today. The average debt for a college graduate in 2015 was $35,000. Eight million former college students are now in default on their student loan debt with no way to discharge that obligation in bankruptcy. Only 49 percent of Millennials manage to graduate college with less than $10,000 in debt, a major shift from the 74 percent of the Baby Boomer generation who were able to do so. According to a recent iQuantifi study, Millennials aged 21-25 shoulder an average of $13,116 in debt. Millennials in their late 20s carry $46,622 and Millennials in their 30s harbor an average of $69,552. All of this presents an enormous headwind that the first time home buyer must overcome.

Under these circumstances, the clearest, most compelling action to grow the housing market would be to do something about Millennials’ student debt. A staggering 56 percent of Millennials between the ages of 18 and 29 who have student loan debt told Bankrate. com that they have delayed major life events because of their debt burden, with home buying the number one thing they have put off doing. Thirty percent of millennials (versus 22% of adults overall) say that student loans have forced them to delay buying a home.

To make it easier for Millennials to leap the other hurdles to home ownership without the deadweight of student debt on their back, some have proposed to go so far as to declare a “jubilee year” and have the nation simply forgive the $1.2 billion in outstanding student loan debt. Home developers might well be a major beneficiary of such a windfall, although bailout of student loan debt at this scale is unlikely to occur any time soon for both financial and political reasons.

A smaller and more personal solution to the problem is offered by the Public Service Loan Forgiveness program. It allows students to have their loans forgiven if they work for government or for certain not-for-profit organizations. Unfortunately, the time period under which a person must serve—ten years for the federal government, for instance— makes the actual impact of this law seem

more like indentured servitude to those working under its provisions.

Other solutions also exist or are under discussion. The Obama administration has greatly expanded eligibility for “income based repayment” (IBR) loans, which limit annual loan payments to a specified percentage of a person’s income, usually ten percent, and are forgiven even if the debt is not fully repaid after 20 to 25 years of payments depending on the particular terms of the original student loan. Some have proposed making IBR loans the standard for all federally guaranteed student loans, while others believe they represent too much risk for the federal government to undertake. Even if this type of loan becomes more prevalent among future home buyers, it still would mean lenders would have to take ten percent of a prospective home buyer’s income off the table when it comes to determining the buyers’ qualifications for a mortgage, thereby lowering the value of a home the buyer might consider.

Some presidential candidates have joined the chorus in favor of allowing student loans to be refinanced, just as many people do with their home loans. About 25 million borrowers are estimated to be locked into higher rates that student loans require today. For these borrowers, such a plan, which many states have also started to explore, would reduce their loan payments by thousands of dollars early in their careers, making it more financially feasible for them to consider taking out a mortgage to buy a house.

The states of Tennessee and Oregon have gone one step further in terms of reducing the scope of this problem in the future. The Republican governor in one state and the Democratic legislature in the other enacted laws that make their community colleges tuition-free. President Obama has proposed doing the same thing for all the nation’s community colleges in partnership with the states. Other communities from Kalamazoo, MI, to El Dorado, AR, have used personal or corporate philanthropy to make all levels of college tuition-free for their high school graduates. The idea continues to spread since the initial program was established in 2005 in Kalamazoo with over 30 cities now offering some form of this benefit to their youth in the hope of increasing the number of families who want to live in their community and stimulating their local economies.

More directly, new home developers and lenders could begin to accept student loans as a fact of life for the Millennial market, and generate innovative new offerings to address the issue. One idea is to rent a home to Millennials under terms that lower the price if they elect to buy it in the future, just as is done with many car leases today. One such experiment is being offered in Miami for two unit town houses whose sales price is 21 percent lower than it would be otherwise. Another would be to find lenders willing to consolidate student debt into a larger home mortgage, with the lender trading the benefits of a loan not dischargeable in bankruptcy to a theoretically safer loan that uses the physical collateral of a house. Finally, builders and banks could take advantage of the Millennial Generation’s love of their parents and build housing designed not just for multi-generational living, but multi-generational financing, with different members of the family responsible for the mortgage payments at different times over the period of the loan.

WHEN MILLENNIALS DO BUY, WHERE WILL THEY LIVE?

Much has been written about where Millennials will buy a home. Some urbanists hope that Millennials will embrace the denser, less suburban lifestyle these pundits favor. Yet survey research and moves by older Millennials belie these assertions.

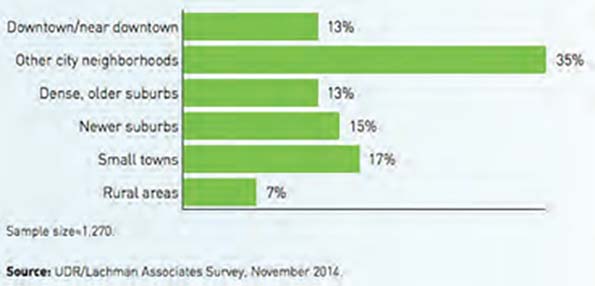

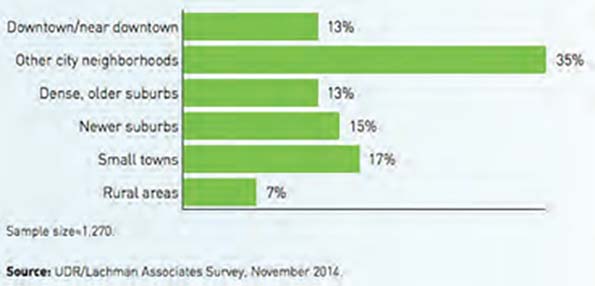

According to the Urban Land Institute’s (ULI) most recent data, only 13 percent of Millennials live in or near downtowns; 63 percent live in other city neighborhoods or suburbs. The number of downtown dwellers was 12 percent in ULI’s 2010 survey. In fact, the Commerce Department reported that more Millennials moved to the suburbs from the city than vice versa in 2014. So even though some young Millennials, especially right after college, do move into urban neighborhoods, which certainly benefit temporarily from their presence, most think of the suburbs when their thoughts turn to raising a family.

The National Association of Home Builders survey in January 2014 found that most of their Millennial respondents intended to purchase a single family home in the suburbs; another survey put the figure at 66 percent. Both studies confirmed the ULI findings that 75 percent of Millennials expected to live in a single family, detached house by the end of the decade. The myth of a new urban dwelling generation largely misreads the difference between “age related” effects and generational attitudes and beliefs.

This misreading has impacted homebuilders who have built fewer homes that Millennials want and can afford, reducing the supply and driving up the price. The result is what economist Jed Kolko calls the “Millennial mismatch—Millennials can afford markets where they don’t live, but they can’t afford many of the markets where they do live.”

(chart: Urban Land Institute’s Gen Y and Housing report, uli.org/wp-content/uploads/ULI-Documents/ Gen-Y-and-Housing.pdf)

One way this lack of affordable housing manifests itself is the continuing phenomenon of Millennials living

in their parents’ house. Despite their improving economic circumstances, a Pew Research Study found that about 42.2 million Millennials, or 67 percent, were living independently in 2014, compared with 42.7 million Millennials, or 71 percent, who did so before the recession in 2007. Since 2010, the percentage of Millennials moving back in with their parents actually increased from 24 percent to 26 percent.xlv While this behavior may temporarily balance the demand for housing with its supply, it greatly increases the number of Millennials missing from the country’s housing market.

HOW TO GET MILLENNIALS BACK IN THE MARKET

There are, however, some examples of what would attract these missing Millennials into the housing market. Almost all of them are successful because they have built upon the most fundamental of Millennial behaviors—the desire to share their experiences. And almost all of them make it possible for Millennials to afford a lifestyle they can share with families and friends.

First on the frugal Millennial’s wish list is the need for the house to be affordable. According to a Rent.com survey of 1,000 Millennial renters, nearly half said they moved to a different city than the one they grew up in, mostly because of the job opportunities that city presented. Given the generation’s strong ties to their family and their friends, this finding puts an exclamation point on how important a consideration affordability is for Millennial first time home buyers.

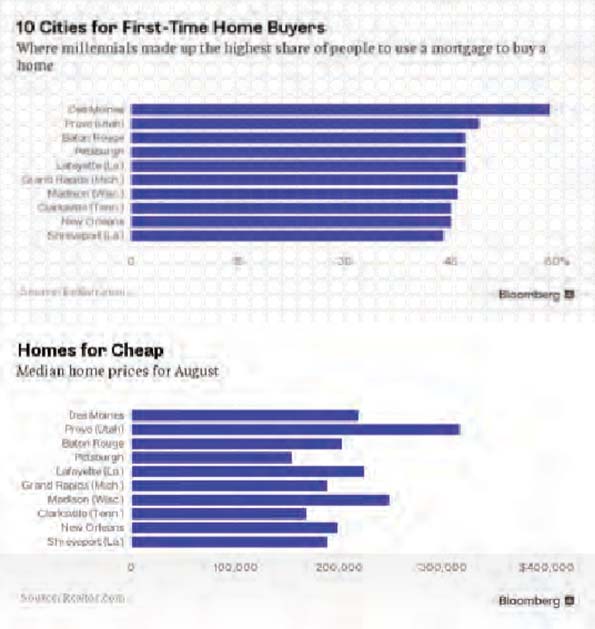

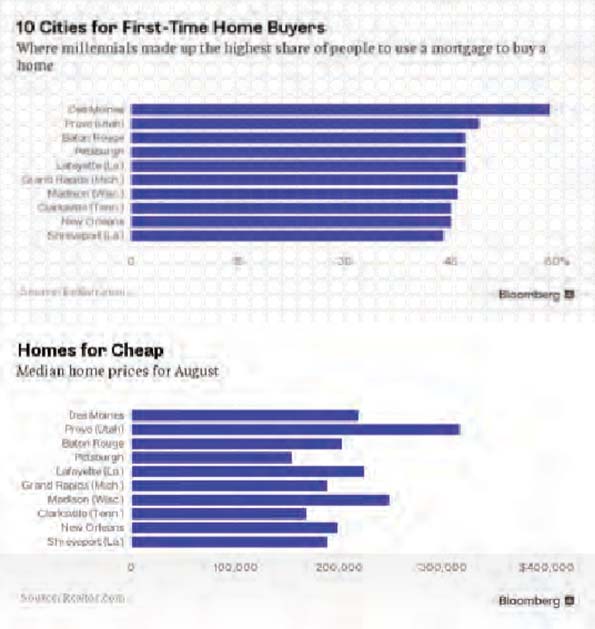

As Millennials continued to enter the housing market, their desire for a more affordable home became evident not just in survey data but actual buying behavior. For instance, 60 percent of those who took out a mortgage to buy a home in August 2015 in Des Moines, Iowa were 25-34 years old. The top ten markets where Millennials dominated the home buying market that month were also ones with very affordable housing prices, with the exception of Provo, Utah. The cheapest big city in America in terms of housing prices, Pittsburgh, was the only one to make the list.

Beyond a place they can afford, the

next thing Millennials want is to own a home they can share with their family and friends. Millennials “want to live where it’s easy to have fun with friends and family, whether in the suburbs or closer in,” says M. Leanne Lachman, one of the authors of the Urban Land Institute’s study. “This is a generation that places a high value on work-life balance and flexibility. They will switch housing and jobs as frequently as necessary to improve their quality of life.”

Only about 28 percent of Millennials told the Demand Institute’s Housing and Community Surveyxlix that they needed grocery stores and restaurants within walking distance of their next home, which is a common characteristic of urban environments. But more than half wanted such amenities to be within a short drive. This creates the demand for compact, livable communities that crop up in less-dense areas, but remain fundamentally suburban albeit with more options for walking, bike-riding and closer shopping. Unfortunately, these characteristics make many places in America, particularly its large coastal metropolitan areas, off limits to young Millennial families. It’s yet another hurdle they must overcome, often sacrificing their desire for shorter commutes to work and time with family to find a place to live that they can afford and safely raise their family.

When they find the place they want to live, Millennials look for the type of housing that makes for a great living experience. It doesn’t have to be large—the most common size of a first time Millennial buyer’s home is less than 1,200 square feet. Half of all homes purchased by Millennials average less than 1,650 square feet and cost less than $148,500. But it does have to be high tech with an open floor plan, making many older homes unsuitable or strictly fixer uppers for this new generation of buyers. For instance, a generation ago, formal dining rooms may have been on every buyer’s wish list, but today they hold little appeal because of the way Millennials entertain. Millennials often convert space originally conceived as a dining room into a home office and move the food fest outside, weather permitting, or into the kitchen where the joys of cooking can be shared.

A majority of Millennial home buyers believe the technological capabilities of a house are more important than “curb appeal.” More than 13 million Americans work from home and all signs point to that trend continuing, especially among high tech Millennial workers. Many of them see their home as a place to “do work,” not just a place to return “after work.” They want to hear about the strength of the mobile carrier’s signal in the house and its Internet speeds, not the embedded infrastructure of cable wires and land lines. Few if any of these desired attributes are present in older suburban tract housing, which further constrains the supply of houses for Millennials, presenting yet another obstacle in their path to home ownership.

Breaking the current chicken and egg standoff between the demand and supply of Millennial style housing will require developers to stop listening to those who claim that Millennials aren’t interested in owning homes—or anything else—and focus on the market opportunity staring them in the face. Realtor.com’s chief economist Jonathan Smoke suggests that the supply of homes for Millennials is the key to igniting the next housing boom. “Despite the increased role of Millennials in the housing market, setbacks still exist and are preventing first timers from making even more of an impact,” says Smoke. “As inventory returns to more normal levels, expect the blooming of Millennial homebuyers to turn into a boom.”

Recent research from Zillow, for instance, found that adults age 22 to 34 were actually more eager to own a home than older Americans.lv If all the surveys of Millennial attitudes weren’t convincing enough, the actual home buying behavior of Millennials who can afford to buy a house should finally get builders off the investment fence. According to Zillow’s data, young married couples in which both partners work own homes at a rate close to or above historical norms for that demographic. Even single employed Millennials are slightly more likely to own a home than their counterparts in the 1970s, 1980s, or 1990s. All that’s needed, it would seem, to bring missing Millennials into the housing market is a larger supply of homes they want to buy. In short, build, builders, build.

Home building, especially construction of single-family stand-alone residences, has not rebounded as much as it should given the last few years of ultralow mortgage rates. For example, the number of single family housing starts and completions were both lower in June than in May of 2015, even as family formations hit highs not seen in a decade. Both of the top two reasons older Millennials gave to realtor.com for not having bought a house yet had to do with the limited supply of affordable housing. It’s not up to Millennials to build the houses they want to buy, it’s up to those with the insights and market leadership skills to step in and create the supply and

knock down this last hurdle to Millennial home ownership.

MISSING MILLENNIALS ARE A ONE TRILLION DOLLAR OPPORTUNITY

A Demand Institute survey of more than 1,000 Millennial households suggests the generation will generate

$1.66 trillion in revenue between now and 2020, using an average home sale price of $200,000, based solely on Millennials’ desire for home ownership and their arrival in the peak new starter home buying ages of 25–34 years old. If current conditions hold, it predicted the number of Millennial households would rise by 8.3 percent over the next five years, from 13.3 million to 21.6 million.

But the Institute’s own data comparing existing home ownership rates among Millennials based on student debt suggests that just removing the burden of student debt would increase these numbers even more. According to their findings, debt elimination would increase the number of home owners among 25–34 year old college graduates by 24 percent, 16 percent among 25–29 year olds, and eight percent for 30–34 year olds.lix Based on the cohort’s current population that would represent over five million more homeowners or $1 trillion in new home purchases. But some portion of that population would actually be forming joint households. If 60 percent marry each other, that would still mean an additional three million new home buyers, or a roughly $600 billion dollar increase in market sales over five years from just this one barrier-busting move.

A separate analysis by John Burns Consulting argued that just the hurdle of student debt cost the U.S. housing market $83 billion dollars in sales last year. They estimate that every $250 in monthly student loan payments decreases home borrowing and purchasing power by $44,000. The number of households

headed by those under 40 who owe at least $250 in monthly student loan payments has tripled since 2005 to 5.9 million. Multiplying those numbers times an average home sale price of $200,000 leads to their $83 billion conclusion—or $415 billion over five years.

Others put the impact on the housing market of missing Millennials at more than twice that level by taking a look at the entire panoply of financial hurdles the generation faces, not just student debt. A Ned Davis Research report suggested these hurdles caused a drop in demand for housing from Millennials of three million homes, for an annual market impact of $600 billion. Their estimate suggests “missing Millennials” represent more than a 1.3 trillion dollar market opportunity over the next five years. Whether the housing market will enjoy that type of revenue growth depends a great deal on how hard it focuses on the hurdles facing this critical home buying cohort.

Although no one is going to wave a magic wand and make student debt disappear overnight, it is possible for government to take

aggressive steps to limit if not eliminate these obligations. Furthermore, easing of credit and down payment requirements would have an immediate impact on Millennials’ decision to buy a new home. More generous parental leave policies on the part of the nation’s employers, either by their own initiative or government mandate, would help accelerate the pace. And policies designed to actually grow wages and expand the economy, such as easier access to affordablehigher education, would certainly help a generation struggling to put together the money they need for a down payment. Longer term policy initiatives designed to increase the supply of housing are certainly worth exploring, but the likelihood that they will be put in place in time to help the bulging number of Millennials moving into early adulthood is not high. Altogether, these initiatives could add at least an extra trillion dollars to the nation’s housing market and make Millennials so much more a part of that market than they are today.

It’s time to give the country’s next great generation, Millennials, the same chance earlier generations had to become home owners. We need to help them overcome the hurdles they face in joining this coveted group of American families. Fortunately, the housing industry has it within its power to take the first steps to provide Millennials their piece of the American Dream, helping ignite a housing boom that will spark an economic boom for the entire nation.

This essay is part of a new report from the Center for Opportunity Urbanism called “America’s Housing Crisis.” The report contains several essays about the future of housing from various perspectives. Follow this link to download the full report (pdf).

Morley Winograd is co-author of the newly published Millennial Momentum: How a New Generation is Remaking America and Millennial Makeover: MySpace, YouTube, and the Future of American Politics and fellow of NDN and the New Policy Institute.