Hillary Clinton, Bernie Sanders and numerous other American politicians want to increase taxes, regulate businesses and create a society where government takes responsibility for many aspects of daily life. If you are sick, the public sector should pay for your treatment and give you sick leave benefits. If you quit your job, taxpayers should support you. If you have a low income, the government should transfer money from your neighbor who has a better job.

The ideal is a society in which the state makes sure that those who work and those who don’t have a similar living standard. These are classical socialist ideas, or as Bernie Sanders himself would explain, the core ideas of social democracy.

Social democracy is becoming increasingly popular among Leftists in the United States. An important reason is that positive role models exist. In fact, a number of countries with social democratic policies — namely, the Nordic nations — have seemingly become everything that the Left would like America to be: prosperous yet equal, and with good social outcomes. Bernie Sanders has said, “I think we should look to countries like Denmark, like Sweden and Norway and learn from what they have accomplished for their working people.”

At first glance, it is not difficult to understand the Left’s admiration for Nordic-style democratic socialism. These countries combine relatively high living standards with low poverty, long life spans and equal income distribution — everything the Left would like America to have. The Left, however, is simply failing to understand the reasons why Nordic societies are so successful. The reason is not large welfare states, but rather a unique culture.

Debunking Utopia – Exposing the myth of Nordic socialism, my new book, details the situation. Many people seem to forget that Nordic countries have not always had large welfare states. During the latter half of the nineteenth century and the first half of the twentieth century, these places were shining examples of small government systems that combined open trade policies with free labor markets and a dynamic market system.

Today, Denmark, for example, stands out as having the highest tax rate among developed nations. But in 1960 the tax rate in the country was merely 25 per cent, lower than 27 percent in the US at the time. In Sweden, the rate was 29 percent, only slightly higher than the US.

During this time, the Nordic countries had already developed equal income distributions, long life spans, low child mortality rates, and high levels of prosperity. The reason is simple. In order to survive the harsh Nordic climate, the people in this part of the world adapted a rigorous work ethic. The Protestant norms of hard work and individual responsibility combined with a system that emphasized protection of private property, limited government and openness to global markets. Income equality grew and poverty was pushed back, thanks to the wealth creating force of markets.

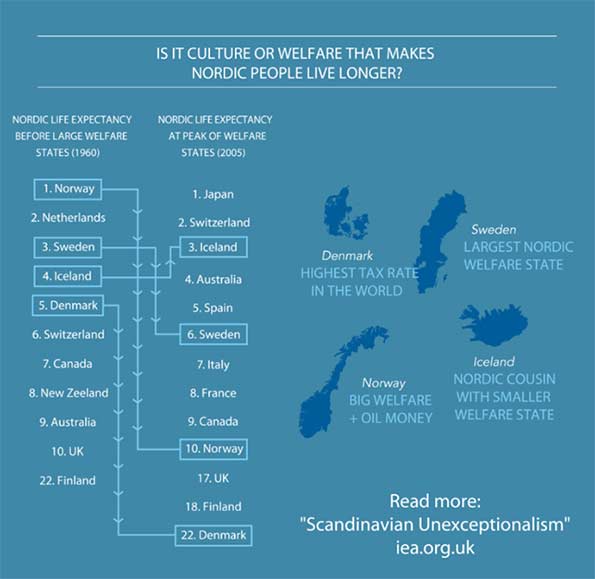

In 1960, well before large welfare states had been created in Nordic countries, Swedes lived 3.2 years longer than Americans, while Norwegians lived 3.8 years longer. After the Nordic countries introduced universal health care, the difference shrunk: today, it is 2.9 years in Sweden and 2.6 years in Norway.

This fact might surprise those who believe that large welfare states lead to longer life spans. Once we study the issue in depth, however, it becomes clear that the explanation is cultural. Nordic people eat healthy diets, run in forests, and avoid the unhealthy lifestyles of many Americans.

In late 2015, a PBS story entitled “What Can The US Learn From Denmark?” stated, “Danes were excited this week to see their calm and prosperous country thrust into the spotlight of the U.S. presidential race when Democratic hopefuls Bernie Sanders and Hillary Clinton sparred over whether there’s something Americans can learn from Denmark’s social model.” The story continued, “Danes get free or heavily subsidized health care” and “compensation when they’re unemployed, out sick from work or on parental leave,” adding that they have longer life spans than Americans.

Now, all these statements are certainly true. The only problem is that the story gives the impression that these facts are directly related. Danes have universal healthcare and government compensation when sick. Correspondingly, they live longer than Americans. So, for the US to raise its life expectancy rates, perhaps a Danish model should be adapted? After all, what kind of heartless monster would oppose policies that increase life spans?

Well, as it turns out, Danes lived 2.4 years longer than Americans in 1960 — when Denmark had lower taxes than the US. Today, the difference has shrunk to 1.5 years. Denmark no longer ranks among the top ten countries in the world in terms of lifespan.

Iceland, the Nordic country with the smallest welfare state, has far surpassed Denmark and the other Nordic countries in terms of life span. The explanation for this success is clearly not a large welfare state. Nor is it that the Icelandic people inhabit a pleasant country. Iceland is cold and dark. It has large, barren, volcanic fields which look much like the fictional Mordor of Lord of the Rings. But the Icelandic people enjoy going out in nature. Also, they eat a healthy diet based to a large extent on fish. The lesson is quite simple: Nordic culture, rather than Nordic-style social democracy, explain the social successes in this part of the world.

The American Left has an idealized, and fully unrealistic, vision of social democracy; a belief that if the US adapts a large welfare state it will magically succeed in this way. There is little if any merit to this viewpoint. Today, Nordic-Americans actually outstrip their cousins in the Nordics both in prosperity and social outcomes.

If we look at another broad measure of social success, child mortality, again we find that yes, Nordic countries indeed do have among the lowest levels in the world. But this too was already the case when these countries had small public sectors. As Sweden, Denmark and Norway introduced large welfare states, if anything they fell somewhat in global ranking. Iceland, on the other hand, climbed the ranking.

The conclusion is clear: Nordic social success pre-dates the modern welfare state, and was if anything more pronounced during the small-government era. Perhaps equally interesting is that while Nordic-style democratic socialism is all the rage among Leftist ideologues in the US, the same policies are to a large degree rejected by the people of the Nordic countries themselves.

After seeing his country held up as an example by in the Democratic presidential debate, the Danish prime minister, Lars Løkke, Rasmussen, objected to the skewed image of socialism in his country. In a speech at Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government, he told students, “I know that some people in the US associate the Nordic model with some sort of socialism. Therefore I would like to make one thing clear. Denmark is far from a socialist planned economy. Denmark is a market economy.”

The remark comes as no surprise. While some US liberals believe that democratic socialism is a flattering label, in the Nordics many are distancing themselves from socialist ideas, pointing out that they, too, embrace the market. In many regards, the Danish government interferes less in the economy than the American government does.

While Denmark does have high taxes and generous welfare policies, today even the Danish Social Democratic Party acknowledges that these policies are slowly eroding responsibility norms, trapping people in welfare dependency and reducing the level of prosperity.

Out of the five Nordic countries, four currently have center-right governments. The only exception is Sweden, in which the Social Democratic Party – which holds the seat of power – has never in its modern history polled as weakly as it does today. Most Swedes vote either for the center-right coalition which wants to reduce the scope of government, or for the right-wing anti-immigration party.

Perhaps these facts are worth pointing out to Bernie Sanders, Hillary Clinton, the journalists at PBS and numerous other Americans who believe that Nordic-style social democracy will transform America to Shangri-La.

Nima Sanandaji is president of the European Centre for Policy Reform and Entrepreneurship. His latest book is Debunking Utopia – Exposing the myth of Nordic socialism.

Copenhagen Harbor Water Bus by Jacob Surland