Urban risk may be understood as a function of hazard, exposure, and vulnerability.1 In metro New Orleans, Katrina-like storm surges constitute the premier hazard (threat); the exposure variable entails human occupancy of hazard-prone spaces; and vulnerability implies the ability to respond resiliently and adaptively—which itself is a function of education, income, age, social capital, and other factors—after having been exposed to the hazard.

This essay measures the extent to which, after the catastrophic deluge triggered by Hurricane Katrina in 2005, residents of metro New Orleans have shifted their settlement patterns and how these movements may affect future urban risk.2 What comes to light is that, at least in terms of residential settlement geographies, the laissez faire rebuilding strategy for flooded neighborhoods proved to be exactly that.

“The Great Footprint Debate” of 2005-2006

An intense debate arose in late 2005 over whether low-lying subdivisions heavily damaged by Katrina’s floodwaters should be expropriated and converted to greenspace. Most citizens and nearly all elected officials decried that residents had a right to return to all neighborhoods. Planners and experts countered by explaining that a population living in higher density on higher ground and surrounded by a buffer of surge-absorbing wetlands would be less exposed to future storms, and would achieve a new level of long-term sustainability.

Despite its geophysical rationality, “shrinking the urban footprint” proved to be socially divisive, politically volatile, and ultimately unfunded. Officials thus had little choice but to abrogate the spatial oversight of the rebuilding effort to individual homeowners, who would return and rebuild where they wished based on their judgment of a neighborhood’s viability.

Federal programs nudged homeowners to return to status quo settlement patterns. Updated flood-zone maps from FEMA’s National Flood Insurance Program, for example, would provide actuarial encouragement to resettle in prediluvial spaces, while the federally funded, state-administered Louisiana Road Home Program’s “Option 1”—to rebuild in place, by far the most popular of the three options—provided grant money to do exactly that.

“Shrinking the urban footprint” became heresy; “greenspacing” took on sinister connotations; and rebuilding in flooded areas came to be valorized as a heroic civic statement. Actor Brad Pitt’s much-celebrated Make It Right Foundation, for example, pointedly positioned its housing initiative along a surge-prone canal, below sea level and immediately adjacent to the single worst Katrina levee breach, to illustrate that if a nonprofit “could build safe, sustainable homes in the most devastated part of New Orleans, [then it] would prove that high-quality, green housing could be built affordably everywhere.”3 Ignoring topography and hydrology gained currency in the discourse of community sustainability even as it flew in the face of environmental sustainability.

A Brief History of New Orleans’ Residential Settlement Patterns, 1718-2005

Topography and hydrology have played fundamental roles in determining where New Orleanians settled since the city’s founding in 1718. The entire region, lying at the heart of the dynamic deltaic plain of the Mississippi River, originally lay above sea level, ranging from a few inches along the marshy perimeter, to a few feet along an interior ridge system, to 8 to 12 feet along the natural levee abutting the Mississippi River.

From the 1700s to the early 1900s, the vast majority of New Orleanians lived on the higher ground closer to the Mississippi. Uninhabited low-lying backswamps, while reviled for their (largely apocryphal) association with disease, nonetheless provided a valuable ecological service for city dwellers, by storing excess river or rain water and safeguarding the city from storm surges. Even the worst of the Mississippi River floods, in 1816, 1849, and 1871, mostly accumulated harmlessly in empty swamplands and, in hindsight, bore more benefits than costs. New Orleanians during the 1700s-1900s were less exposed to the hazard of flooding because the limitations of their technology forced them to live on higher ground.4

Circumstances changed in the 1890s, when engineers began designing and installing a sophisticated municipal drainage system to enable urbanization to finally spread across the backswamp to the Gulf-connected brackish bay known as Lake Pontchartrain. A resounding success from a developmental standpoint, the system came with a largely unforeseen cost. As the pumps removed a major component of the local soil body—water— it opened up cavities, which in turn allowed organic matter (peat) to oxidize, shrink, and open up more cavities. Into those spaces settled finely textured clay, silt, and sand particles; the soil body thus compacted and dropped below sea level. Over the course of the twentieth century, former swamps and marshes in places like Lakeview, Gentilly, and New Orleans East sunk by 6-10 feet, while interior basins such as Broadmoor dropped to 5 feet below sea level. New levees were built along the lakefront, and later along the lateral flanks, were all that prevented outside water from pouring into the increasingly bowl-shaped metropolis.

Nevertheless, convinced that the natural factors constraining their residential options had now been neutralized, New Orleanians migrated enthusiastically out of older, higher neighborhoods and into lower, modern subdivisions. Between 1920 and 1930, nearly every lakeside census tract at least doubled in population; low-lying Lakeview increased by 350 percent, while parts of equally low Gentilly grew by 636 percent. Older neighborhoods on higher ground, meanwhile, lost residents: Tremé and Marigny dropped by 10 to 15 percent, and the French Quarter declined by one-quarter. The high-elevation Lee Circle area lost 43 percent of its residents, while low-elevation Gerttown increased by a whopping 1,512 percent.5

The 1960 census recorded the city’s peak of 627,525 residents, double the population from the beginning of the twentieth century. But while nearly all New Orleanians lived above sea level in 1900, only 48 percent remained there by 1960; fully 321,000 New Orleanians had vertically migrated from higher to lower ground, away from the Mississippi River and northwardly toward the lake as well as into the suburban parishes to the west, east, and south.6

Subsequent years saw additional tens of thousands of New Orleanians migrate in this pattern, motivated at first by school integration and later by a broader array of social and economic impetuses. By 2000, the Crescent City’s population had dropped by 23 percent since 1960, representing a net loss of 143,000 mostly middle-class white families to adjacent parishes. Of those that remained, only 38 percent lived above sea level.7

Meanwhile, beyond the metropolis, coastal wetlands eroded at a pace that would reach 10-35 square miles per year, due largely to two main factors: (1) the excavation through delicate marshes of thousands of miles of erosion-prone, salt-water-intruding navigation and oil-and-gas extraction canals, and (2) the leveeing of the Mississippi River, which prevented springtime floods but also starved the delta of new fresh water and vital sediment. Gulf waters crept closer to the metropolis’ floodwalls and levees, while inside that artificial perimeter of protection, land surfaces that once sloped gradually to the level of the sea now formed a series of topographic bowls straddling sea level.

When those floodwalls and levees breached on August 29, 2005, sea water poured in and became impounded within those topographic bowls, a deadly reminder that topography still mattered. Satellite images of the flood eerily matched the shape of the undeveloped backswamp in nineteenth-century maps, while those higher areas that were home to the historical city, quite naturally, remained dry.

But the stark geo-topographical history lesson could only go so far in convincing flood victims to move accordingly; after all, they still owned their low-lying properties, and real estate on higher terrain was anything but cheap and abundant. Besides, New Orleanians in general rightfully felt that they had been scandalously wronged by federal engineering failures, and anything short of full metropolitan reconstitution came to be seen as defeatist and unacceptable. Most post-Katrina advocacy thus focused on reinforcing the preexisting technological solutions that kept water out of the lowlands, rather than nudging people toward higher ground. “Shrink the urban footprint” got yelled off the table; “Make Levees, Not War” and “Category-5 Levees Now!” became popular bumper-sticker slogans; and “The Great Footprint Debate” became a bad memory.

Resettlement in Vertical Space

The early repopulation of post-Katrina New Orleans defied easy measure. Residents living “between” places as they rebuilt, plus temporarily broken-up families, peripatetic workers, and transient populations all conspired to make the city’s 2006-2009 demographics difficult to estimate, much less map. The 2010 Census finally provided a precise number: 343,829. By 2014, over 384,000 people lived in Orleans Parish, or eighty percent of the pre-Katrina figure. Of course, not all were here prior; one survey determined roughly 10 percent of the city’s postdiluvian population had not lived here before 2005.8

How had the new population resettled in terms of topographic elevation? We won’t know precisely until 2020, because only the decennial census provides actual headcounts aggregated at sufficiently high spatial resolution (the block level) for this sort of analysis; annual estimates from the American Community Survey do not suffice. Thus we must make do with the 2010 Census. While much has changed during 2010-2015, the macroscopic settlement geographies under investigation here had largely had fallen into place by 2010.

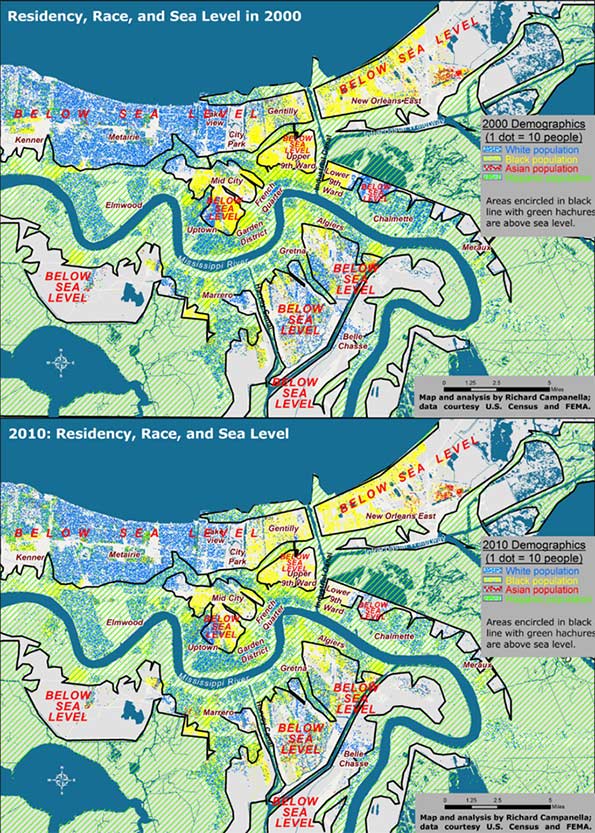

Figure 1. Residential settlement above and below sea level, 2000 and 2010; analysis and maps by Richard Campanella.

When intersected with high-resolution LIDAR-based digital elevation models, the 2010 Census data show that residents of metro New Orleans shifted to higher ground by only 1 percent compared to 2000 (Figure 1). Whereas 38 percent of metro-area residents lived above sea level in 2000, 39 percent did so by 2010, and that differentiation generally held true for each racial and ethnic group. Whites shifted from 42 to 44 percent living above sea level; African Americans 33 to 34 percent, Hispanics from 30 to 29 percent, and Asians 20 to 22 percent.

Clearly, elevation did not exercise much influence in resettlement decisions, and people distributed themselves in vertical space in roughly the same proportions as before the flood. Yet there is one noteworthy angle to the fact that the above-sea-level percentage has risen, albeit barely (38 to 39 percent): it marked the first time in New Orleans history that the percent of people living below sea level has actually dropped.

What impact did the experience of flooding have on resettlement patterns? Whereas people shifted only slightly out of low-lying areas regardless of flooding, they moved significantly out of areas that actually flooded, regardless of elevation. Inundated areas lost 37 percent of their population between 2000 and 2010, with the vast majority departing after 2005. They lost 37 percent of their white populations, 40 percent of their black populations, and 10 percent of their Asian populations. Only Hispanics increased in the flooded zone, by 10 percent, in part because this population had grown dramatically region-wide, and because members of this population sometimes settled in neighborhoods they themselves helped rebuild.

The differing figures suggest that while low-lying elevation theoretically exposes residents to the hazard of flooding, the trauma of actually flooding proved to be, sadly, much more convincing.

Resettlement in Horizontal Space

Contrasting before-and-after residential patterns in horizontal space may be done through traditional methods such as comparative maps and demographic tables. What this investigation offers is a more singular and synoptical depiction of spatial shifts: by computing and comparing spatial central tendencies, or centroids.

A centroid is a theoretical center of balance of a given spatial distribution. A population centroid is that point around which people within a delimited area are evenly distributed.9

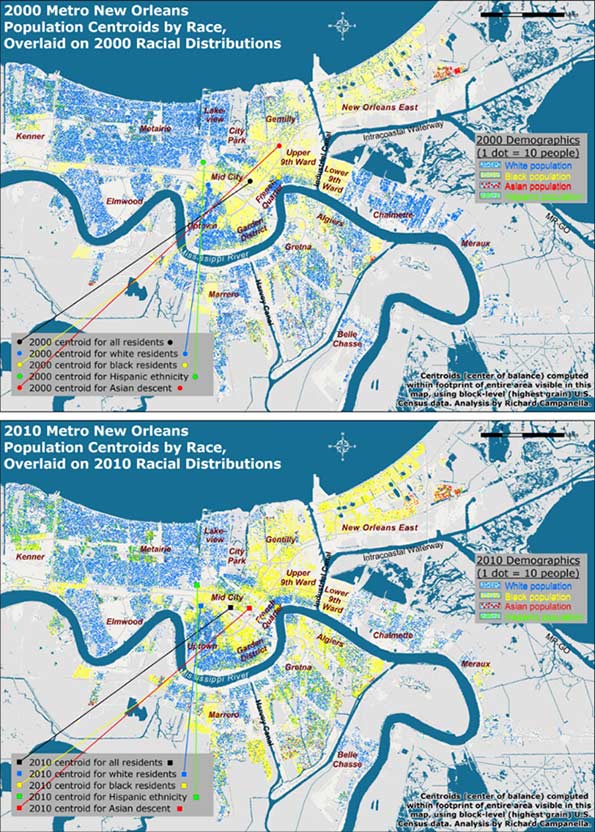

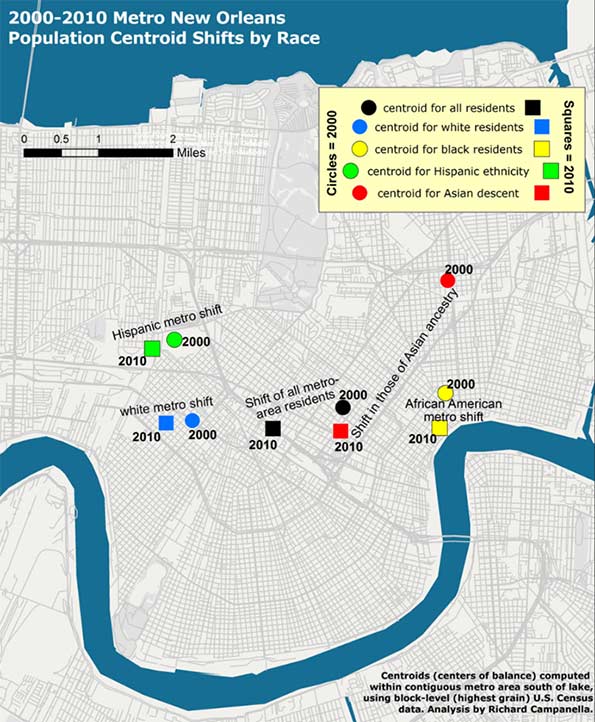

Centroids capture complex shifts of millions of data with a single point. But they do not tell the entire story. A centroid for a high-risk coastal area, for example, may shift inland not because people have moved away from the seashore, but because previous residents decided not to return there. It’s also worth noting it takes a lot to move a centroid, as micro-scale shifts in one area are usually offset by countervailing shifts elsewhere. Thus, apparent minor centroid movements can actually be significant. Following are the centroid shifts for metro New Orleans broken down by racial and ethnic groups (Figures 2 and 3).

In 2000, five years before the flood, there were 1,006,783 people living within the metro area as delineated for this particular study, of whom 512,696 identified their race as white; 435,353 as black; 25,941 as Asian; and 50,451 as Hispanic in ethnicity. Five years after the flood, these figures had changed to 817,748 total population, of whom 416,232 were white; 327,972 were black; 27,562 were Asian, and 75,397 were Hispanic.10 When their centroids are plotted, they show that metro residents as a whole, and each racial/ethnic sub-group, shifted westward and southward between 2000 and 2010, away from the location of most of the flooding and away from the source of most of the surge, which generally penetrated the eastern and northern (lakeside) flanks of the metropolis.

Did populations proactively move away from risk? Not quite. What accounts for these shifts is the fact that the eastern half of the metropolis bore the brunt of the Katrina flooding, and the ensuing destruction meant populations here were less likely to reconstitute by 2010, which thus nudged centroids westward. Additionally, flooding from Lake Pontchartrain through ruptures in two of the three outfalls (drainage) canals disproportionally damaged the northern tier of the city, namely Lakeview and Gentilly. Combined with robust return rates in the older, higher historical neighborhoods along the Mississippi, as well as the unflooded West Bank (which sit to the south and west of the worst-damaged areas), they abetted a southwestward shift of the centroids. In a purely empirical sense, this change means more people now live in less-exposed areas. But, as we saw with the vertical shifts, the movements are more a reflection of passive responses to flood damage than active decisions to avoid future flooding.

Figure 2. Population centroids by race and ethnicity for metro New Orleans, 2000-2010; see next figure for detailed view. Analysis and maps by Richard Campanella.

Figure 3. A closer look at the metro-area population centroid shifts by race and ethnicity, 2000-2010; analysis and map by Richard Campanella.

Reflections

Resettlement patterns in metro New Orleans have only marginally reduced residential exposure to the hazard of storm surge. In the vertical dimension, metro-area residents today occupy below-sea-level areas at only a slightly lower rate than before the deluge, 61 percent as opposed to 62 percent, although that change represents the first-ever reverse (decline) of the century-long drift into below-sea-level areas. Likewise, residents’ horizontal shifts, which were in southwestward directions, seemed to suggest a movement away from hazard, but these shifts were more a product of passive than active processes .

Metro New Orleans, it is important to note, has substantially reduced its overall risk—but mostly thanks to its new and improved federal Hurricane & Storm Damage Risk Reduction System (HSDRRS) rather than shifts in residences. No longer called a “protection” system, the Risk Reduction System is a $14.5 billion integrated network of raised levees, strengthened floodwalls, barriers, gates, and pumps built by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and its contractors to protect the metropolis from the surges accompanying storms with a 1-percent chance of occurring in any given year.11 The HSDRRD, which worked well during Hurricane Isaac’s surprisingly strong surge in 2012, has given the metropolis a new lease on life, at least for the next few decades. But all other risk drivers—the condition of the coastal wetlands, subsidence and sea level rise, social vulnerability, and, as evidenced in this paper, exposure—have either slightly worsened, only marginally improved, or generally remained constant.

The exposure-related patterns reported here reflect who won the “Great Footprint Debate” ten years ago.12 Months after Katrina, when it became clear that no neighborhoods would be closed and the urban footprint would persist, decisions driving resettlement patterns in the flooded region effectively transferred from leaders to homeowners. Rather inevitably, the laissez faire rebuilding strategy proved to be exactly that, and people generally repopulated areas they had previously occupied, though at markedly varied densities.

Ten years later, the resulting patterns are a veritable Rorschach Test. Some observers look to the 75-90 percent repopulation rates of certain flooded neighborhoods and view them as heroically high, proof of New Orleanians’ resilience and love-of-place. Others point to the 25-50 percent rates of other areas and call them scandalously low, evidence of corruption and ineptitude. Still others might point to the thousands of scattered blighted properties and weedy lots and concede—as St. Bernard Parish President David Peralta admitted on the ninth anniversary of Hurricane Katrina—that “we probably should have shrunk the footprint of the parish at the very beginning.”13

As for the HSDRRS, continual subsidence and erosion vis-à-vis rising seas, coupled with costly and as-yet undetermined maintenance and certification responsibilities, will gradually diminish the safety dividend provided by this remarkable system. The nation’s willingness to pay for continued upkeep, meanwhile, may grow tenuous; indeed, it’s not even a safe bet locally. Voters in St. Bernard Parish, which suffered near-total inundation from Katrina, defeated not once but twice a tax to pay for drainage and levee maintenance, a move that may well increase flood insurance rates.14

Residents throughout the metropolis appear to be repeating the same mistakes they made during the twentieth century: of dismissing the importance of natural elevation, of over-relying on engineering solutions, of under-maintaining these structures in a milieu of scarce funds, and of developing a false sense of security about flood “protection.”

We need to recognize the limits of our ability to neutralize hazards—that is, to presume that levees will completely protect us from storm surges—while appreciating the benefits of reducing our exposure to them. Beyond the metropolis, this means aggressive coastal restoration using every means available as soon as possible, an effort that may well require some expropriations. Within the metropolis, it means living on higher ground or otherwise mitigating risk. In the words of University of New Orleans disaster expert Dr. Shirley Laska, “mitigation, primarily elevating houses, is [one] way to achieve the affordable flood insurance…. It is possible to remain in moderately at-risk areas using engineered mitigation efforts, combined with land use planning that restricts development in high-risk areas.”15

Planning that restricts development in high-risk areas: this was the same reasoning behind the “shrink the urban footprint” argument of late 2005—and anything but the laissez faire strategy that ensued.

Bio

Richard Campanella, a geographer with the Tulane School of Architecture, is the author of “Bienville’s Dilemma,” “Geographies of New Orleans,” “Delta Urbanism,” “Bourbon Street: A History,” and other books. His articles may be read at http://richcampanella.com , and he may be reached at rcampane@tulane.edu or @nolacampanella on Twitter.

Acknowledgements

The author wishes to thank Gulf of Mexico Program Officer Kristin Tracz of the Walton Family Foundation, Dr. Shirley Laska, and the Gulf Coast Restoration Fund at New Venture Fund, and Tulane School of Architecture, as well as Garry Cecchine, David Johnson, and Mark Davis for their reviews.

1 David Crichton, “The Risk Triangle,” in Natural Disaster Management, edited by J. Ingleton (Tudor Rose, London, 1999), pp. 102-103.

2 In this paper, “metro New Orleans” means the conurbation (contiguous urbanized area shown in the maps) of Orleans, Jefferson, western St. Bernard, and upper Plaquemines on the West Bank (Belle Chasse); it excludes the outlying rural areas of these parishes, such as Lake Catherine, Grand Island, and Hopedale, and does not include the North Shore or the river parishes.

3 Brad Pitt, as cited in “Make It Right—History,” http://makeitright.org/about/history/, visited February 13, 2015.

4 Richard Campanella, Bienville’s Dilemma: A Historical Geography of New Orleans and Geographies of New Orleans (University of Louisiana Press, 2006, 2008); R. Campanella, Delta Urbanism: New Orleans (American Planning Association, 2010); R. Campanella, “The Katrina of the 1800s Was Called Sauve’s Crevasse,” Times-Picayune, June 13, 2014, and other prior works by the author.

5 H. W. Gilmore, Some Basic Census Tract Maps of New Orleans (New Orleans, 1937), map book stored at Tulane University Special Collections, C5-D10-F6.

6 Richard Campanella, Bienville’s Dilemma: A Historical Geography of New Orleans (University of Louisiana Press, 2008) and other prior works by the author.

7 Coincidently, 38 percent of all residents of the contiguous metropolis south of Lake Pontchartrain also lived above sea level in 2000. Thus, at both the city and metropolitan level, three out of every eight residents lived above sea level and the other five resided below sea level. All figures calculated by author using highest-grain available historical demographic data, usually from the U.S. Census, and LIDAR-based high-resolution elevation data captured in 1999-2000 by FEMA and the State of Louisiana.

8 Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation, “New Orleans Five Years After the Storm: A New Disaster Amid Recovery” (2010), http://kaiserfamilyfoundation.files.wordpress.com/2013/02/8089.pdf

9 Defining the study area is essential when reporting centroids. New Orleans proper, the contiguous metro area, and the Metropolitan Statistical Area, which includes St. Tammany and other outlying parishes, would all have different population centroids. This study uses the metro area south of the lake shown in the accompanying maps. It is also important to use the finest-grain—that is, highest spatial resolution—demographic data to compute centroids, as coarsely aggregated data carries with it a wider margin of error. This study uses block-level data from the decennial U.S. Census, the finest available.

10 Figures do not sum to totals because some people chose two or more racial categories while others declined the question, and because Hispanicism is viewed by the Census Bureau as an ethnicity and not a race.

11 For details on this system, see http://www.mvn.usace.army.mil/Missions/HSDRRS.aspx

12 Richard Campanella, Bienville’s Dilemma: A Historical Geography of New Orleans (University of Louisiana Press, 2008), pp. 344-355.

13 David Peralta, as quoted by Benjamin Alexander-Bloch, “Hurricane Katrina +9: Smaller St. Bernard Parish Grappling with Costs of Coming Back,” Times-Picayune/NOLA.COM, August 29, 2014.

14 Mark Schleifstein, “St. Bernard Tax Defeat Means Higher Flood Risk, Flood Insurance Rates, Levee Leaders Warn,” Times-Picayune/NOLA.COM, May 4, 2015, http://www.nola.com/environment/index.ssf/2015/05/st_bernard_tax_defeat_means_hi.html ; see also Richard Campanella, “The Great Footprint Debate, Updated,” Times-Picayune/NOLA.COM, May 31, 2015.

15 Shirley Laska, email communication with author, April 12, 2015.

Replicating Bourbon Street

Editor’s note: following is an excerpt from Tulane University geographer Richard Campanella’s new book, “Bourbon Street: A History” (LSU Press, 2014), which traces New Orleans’ most famous and infamous space from its obscure colonial origins to its widespread reknown today. This chapter, titled “Replicating Bourbon Street: Spatial and Linguistic Diffusion” and drawn from a section called “Bourbon Street as a Social Artifact,” recounts how this brand has spread worldwide and become part of the language—to both the benefit and chagrin of New Orleans.

Perhaps the best evidence of Bourbon Street’s success is the fact that, like jazz, it has diffused worldwide. It’s a claim few other streets can make. As early as the 1950s, a nightclub named “Bourbon Street” operated in New York City, and apparently successfully, because in 1957 the Dupont family formed a corporation to purchase it with plans to bring “Mambo City” entertainment to clubs named Bourbon Street in Miami and Chicago.1 Today, at least 160 businesses throughout the United States and Canada have “Bourbon Street” in their names and themes; 77 percent are restaurants, bars, and clubs; 11 percent are retailers (mostly of party and novelty items); and the remainder are caterers, banquet halls, hotels, and casinos—more eating, drinking, and entertaining. They span coast to coast, from Key West to Edmonton and from San Diego to Montreal. Greater New York has eleven, while Calgary has six, as does San Antonio (mostly near the River Walk, “the Bourbon Street of San Antonio”). Greater Toronto has sixteen, most of them franchises of the Innovated Restaurant Group’s “Bourbon St. Grill” chain—including one on Yonge Street, which has been described as “the Bourbon Street of Toronto.” There are also Bourbon-named restaurants, bars, and clubs in London, Amsterdam, Hamburg, Naples, Moscow, Tokyo, Shanghai, Dubai, and many other world cities. These replicas enthusiastically embrace Bourbon Street imagery and material culture (lampposts, balconies, Mardi Gras jesters, beads) in their signage, décor, and Web sites. Menus attempt to deliver the spice and zest deemed intrinsic to this perceptual package, as does the atmospheric music. How convincingly do these meta-Bourbons replicate the original? A review of one such venue in Amsterdam (“the New Orleans of Europe”) could easily apply to the actual street:

[T]he jovial Bourbon Street Jazz and Blues Club…attracts a casual, jean-clad crowd of all ages [dancing to] cover bands with a pop flavor [or] blues rhythms. Three glass chandeliers hanging over the bar provide an incongruous dash of glamour to an otherwise low-key and comfortable scruffy décor.2

In this spatial dissemination we see a trend: while local replication of the Bourbon Street phenomenon usually takes the form of competition tinged with contempt (witness the “anti-Bourbons”), external replicas of Bourbon Street view themselves as payers of homage to the “authentic” original, and modestly present themselves as the next best thing without the airfare. No licenses are needed in replicating Bourbon Street; there are no copyrights, trademarks, or royalties due. The name, phenomenon, and imagery are all in the public domain, a valuable vernacular brand free for anyone to appropriate. Try doing that to The New Orleans Jazz and Heritage Festival Presented by Shell and you’d have a lawsuit on your hands.

Bourbon is also among the few streets to be replicated structurally—by the State of Louisiana, which sponsored a three-acre exhibit at the 1964 World’s Fair in Queens, New York. It featured all the standard architectural tropes of the French Quarter topped off with a huge arch emblazoned LOUISIANA’S BOURBON STREET accompanied by towering Carnival royalty. In typical Louisiana fair tradition, however, the exhibit experienced construction delays and filed for bankruptcy, which caused the state to wash its hands of the fiasco and officially change the name of the exhibit to “Bourbon Street.” “The so-called Louisiana area in its present condition,” state officials solemnly proclaimed, “reflects discredit upon the State of Louisiana, its culture, heritage and people.” Wags pointed out that this was pretty much what locals thought of the original Bourbon Street. But unlike the original, a corporate entity named Pavilion Properties, Inc. took over the exhibit, and after removing all references to Louisiana and spiffing up the props, it managed the Creole food booths, Dixieland trios, sketch artists, organ grinders, street performers, and nightclubs (including the popular “Gay New Orleans”) for the remainder of the fair. Also unlike the original, Pavilion Properties’ exhibit, just like the state’s attempt, failed commercially and also filed for bankruptcy. Nevertheless, it introduced a generation of New Yorkers to the Bourbon Street brand.3

At the opposite end of the country two years later, another private-sector entity built a “New Orleans Square” at Disneyland. Based on field research conducted in the French Quarter by Walt Disney himself plus a staff of artists in 1965, the $13.5 million West Coast replica (nearly the cost of the Louisiana Purchase, Disney joked) eschewed the Bourbon moniker, presumably not to scare off parents, but nevertheless incorporated everything that worked on the real Bourbon Street minus the breasts and booze. Disney later replicated New Orleans Square at its Adventureland in Tokyo (1983), which may partly explain the popularity of the real New Orleans with Japanese visitors today. It did not, however, build a New Orleans Square at Disneyland Paris (Euro Disney) when it opened in 1992.4

Bourbon Street has also been thematically and structurally referenced in countless shopping malls, amusement parks, casinos, cruise ship parties, festivals, convention banquets, and wedding receptions, not to mention on film and theatrical sets and in computer animation for movies like The Princess and the Frog. “Bourbon Street” as an adjective has found its way onto menus, usually for spicy dishes, and into household décor, generally to describe old-world filigree inspired by the iron-lace balconies. It’s a case study of cultural diffusion which serves as free worldwide advertising for the original, across various media forms and demographic cohorts, all with zero encouragement and oversight from Bourbonites. Now that’s success.

Imitation may be the sincerest form of flattery, but it also produces competition. Once there was a time when the forbidden pleasures available on Bourbon Street were in high demand and low supply nationwide, particularly in the South. That made Bourbon Street valuable. Today the nation is a whole lot less judgmental about pleasure and much better supplied with comparable pleasure districts. A visit to Galveston’s The Strand, St. Louis’ Soulard, and Mobile’s Dauphine Street, all of which have adopted Bourbon-style Mardi Gras, may satisfy many people’s desire for the escapism that Bourbon Street once monopolized. Even just a few blocks away in downtown New Orleans, Harrah’s has quietly overseen the creation of a Bourbon alternative on the Fulton Street Mall, complete with outdoor dining, festival space, and a growing inventory of venues, all adjacent to the corporation’s hotel and casino. Might such meta-Bourbons erode the market share of the original, in the same way that regional casinos have chipped away at Las Vegas’ domination? Bourbonites would be ill-advised to rely on their fame; better to experiment with innovations, rediscover what worked in the past, and tame that which damages. That said, The Street does have certain inherent advantages: it’s bigger and longer than the competition; it’s embedded into the world-famous French Quarter and enjoys a symbiotic relationship with its tourism industry; and perhaps most importantly, it boasts that intimate historical streetscape and centuries-old civic reputation that infuses in visitors a certain credibility—shall we call it authenticity?—in a way unmatched by places like Las Vegas. On a dark note, Bourbon is also disturbingly vulnerable to accidental or intentional trauma, such as a balcony collapse, crowd stampede, or terrorist bombing, which, in addition to the human toll, could poison The Street’s allure for years. Bourbon, in short, has bright prospects and a record of widespread economic and cultural influence, but should not take its fame and success for granted.

Speaking of cultural influence, Bourbon Street has entered the language of American English, which, curiously, does not have a perfect word for the Bourbon Street phenomenon. Shall we call it an adult entertainment area? A cluster? A strip? A pedestrian mall? A tenderloin, red-light, or vice district? All are awkward, some are imprecise, and none are perfect. The linguistic lacuna is particularly perplexing because nearly every city since Sybaris has developed such spaces.

To fill the gap, some speakers convert common nouns into proper toponyms; examples include Las Vegas’ The Strip, Baltimore’s The Block, and historic New Orleans’ The Swamp or The Line. Others craft “antonamasias,” which, in rhetoric, are attempts to describe the characteristics of a new phenomenon by invoking the name of a comparable known entity, e.g., “the Paris of…,” “the Barbary Coast of…,” “the Greenwich Village of….”5 The antonamasia “the Bourbon Street of….” is among the most popular ways for Americans to refer efficiently and effectively to pedestrian-scale drinking, eating, and entertainment districts. It’s exceedingly common to hear 6th Street, for example, described as the Bourbon Street of Austin. Ybor City is routinely characterized as the Bourbon Street of Tampa, as is Carson Street of Pittsburgh, and Duval Street of Key West (or of the entire Caribbean). Beale Street was completely redeveloped by a real estate corporation in the 1980s from a boarded-up eyesore to become, inevitably, the Bourbon Street of Memphis. A review of 67 published articles since 1986, plus over 300 Internet sources, showed that at least eighty social spaces worldwide have been described as “the Bourbon Street of” their respective communities. They span from Hamburg’s Reeperbahn to Bangkok’s Patpong; from Spain’s Pamplona during the Running of the Bulls to Las Ramblas in Barcelona, from Quay Street in Galway to Lan Kwai Fong in Hong Kong. They are not always urban; sometimes the phrase it used for frisky beaches at vacation destinations, for boating coves (most notoriously in Lake of the Ozarks, a popular rendezvous for nudity and inebriation), or the Mall of America in Minneapolis, the entire town of Hyannis (“the Bourbon Street of the Cape”) or the city of Ogden (“the Bourbon Street of Utah,” historically). Some use it as a warning (“Let’s not turn the Underground into the Bourbon Street of Atlanta”) or as an ambition (“the big goal is for the Mill Avenue District to become the Bourbon Street of the Southwest”). The phrase even found a home in its own backyard; a travel writer called “Jackson Square…the Bourbon Street of daytime New Orleans,” and the Times-Picayune dubbed the Fulton Street Mall as “the Bourbon Street of the [1984] world’s fair.” Some uses emphasize the spatial clustering over the piquant aspect (“Canyon Road [is] the Bourbon Street of Santa Fe’s art scene”); others do the exact opposite: “USA Network [is] the Bourbon Street of basic cable;” “Louisiana Fried Chicken [is] the Bourbon Street of chicken.”6

One would be hard-pressed to think of another street so richly representational. The very matriculation of a street to metaphor status is fairly rare. To be sure, we speak of Wall Street to mean corporate power, Madison Avenue to mean marketing, and Broadway for theater, but as we go further down the list, we find fewer linguistic uses and users. Bourbon Street is one of the American English language’s handiest and most evocative place metaphors, a testament to The Street’s widespread renown and iconic resonance.

Richard Campanella, a geographer with the Tulane School of Architecture, is the author of Bienville’s Dilemma, Geographies of New Orleans, Lincoln in New Orleans, and Bourbon Street: A History (LSU Press, 2014), from which this article was excerpted. Please see the book for sources. Campanella may be reached through http://richcampanella.com or rcampane@tulane.edu ; and followed on Twitter at @nolacampanella.

1 “Dupont Dough Backs Murphy,” Billboard, December 2, 1957, p. 19.

2 Corinne LaBalme, “Night Moves of All Kinds: The Club Scene in Seven Cities—Amsterdam,” The New York Times, September 17, 2000.

3 Francis Stilley, “Visitors to World’s Fair Will ‘Ride Magic Carpet,’ Times-Picayune, April 15, 1964; “Hot Flashes,” Times-Picayune, May 31, 1964, p. 37; Charles M. Hargroder, “Governor, Firm Announce Plant,” Times-Picayune, June 17, 1964, pp. 1-16; Richard Phalon, “Bourbon Street Operator at Fair Is 11th Bankrupt Exhibitor,” New York Times, February 5, 1965, p. 32.

4 “Disneyland N.O. Replica, Aim,” Times-Picayune, April 11, 1965, p. 17.

5 I thank sociolinguist Christina Schoux Casey for informing me of this obscure but useful term.

6 Research by author using hundreds of news and online sources, 1986-present, searched throughout 2012.

Gentrification and its Discontents: Notes from New Orleans

Readers of this forum have probably heard rumors of gentrification in post-Katrina New Orleans. Residential shifts playing out in the Crescent City share many commonalities with those elsewhere, but also bear some distinctions and paradoxes. I offer these observations from the so-called Williamsburg of the South, a neighborhood called Bywater.

Gentrification arrived rather early to New Orleans, a generation before the term was coined. Writers and artists settled in the French Quarter in the 1920s and 1930s, drawn by the appeal of its expatriated Mediterranean atmosphere, not to mention its cheap rent, good food, and abundant alcohol despite Prohibition. Initial restorations of historic structures ensued, although it was not until after World War II that wealthier, educated newcomers began steadily supplanting working-class Sicilian and black Creole natives.

By the 1970s, the French Quarter was largely gentrified, and the process continued downriver into the adjacent Faubourg Marigny (a historical moniker revived by Francophile preservationists and savvy real estate agents) and upriver into the Lower Garden District (also a new toponym: gentrification has a vocabulary as well as a geography). It progressed through the 1980s-2000s but only modestly, slowed by the city’s abundant social problems and limited economic opportunity. New Orleans in this era ranked as the Sun Belt’s premier shrinking city, losing 170,000 residents between 1960 and 2005. The relatively few newcomers tended to be gentrifiers, and gentrifiers today are overwhelmingly transplants. I, for example, am both, and I use the terms interchangeably in this piece.

One Storm, Two Waves

Everything changed after August-September 2005, when the Hurricane Katrina deluge, amid all the tragedy, unexpectedly positioned New Orleans as a cause célèbre for a generation of idealistic millennials. A few thousand urbanists, environmentalists, and social workers—we called them “the brain gain;” they called themselves YURPS, or Young Urban Rebuilding Professionals—took leave from their graduate studies and nascent careers and headed South to be a part of something important.

Many landed positions in planning and recovery efforts, or in an alphabet soup of new nonprofits; some parlayed their experiences into Ph.D. dissertations, many of which are coming out now in book form. This cohort, which I estimate in the low- to mid-four digits, largely moved on around 2008-2009, as recovery moneys petered out. Then a second wave began arriving, enticed by the relatively robust regional economy compared to the rest of the nation. These newcomers were greater in number (I estimate 15,000-20,000 and continuing), more specially skilled, and serious about planting domestic and economic roots here. Some today are new-media entrepreneurs; others work with Teach for America or within the highly charter-ized public school system (infused recently with a billion federal dollars), or in the booming tax-incentivized Louisiana film industry and other cultural-economy niches.

Brushing shoulders with them are a fair number of newly arrived artists, musicians, and creative types who turned their backs on the Great Recession woes and resettled in what they perceived to be an undiscovered bohemia in the lower faubourgs of New Orleans—just as their predecessors did in the French Quarter 80 years prior. It is primarily these second-wave transplants who have accelerated gentrification patterns.

Spatial and Social Structure of New Orleans Gentrification

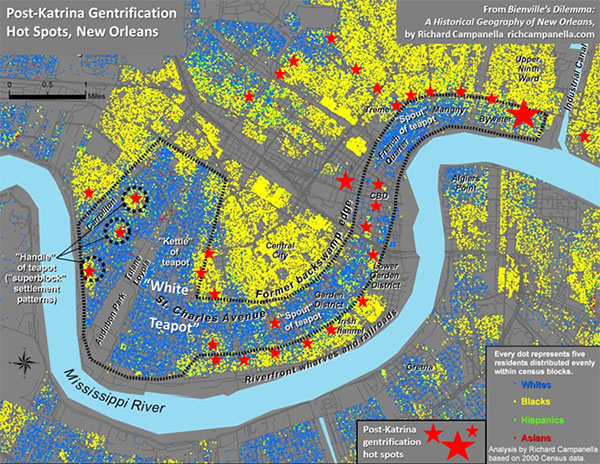

Gentrification in New Orleans is spatially regularized and predictable. Two underlying geographies must be in place before better-educated, more-moneyed transplants start to move into neighborhoods of working-class natives. First, the area must be historic. Most people who opt to move to New Orleans envision living in Creole quaintness or Classical splendor amidst nineteen-century cityscapes; they are not seeking mundane ranch houses or split-levels in subdivisions. That distinctive housing stock exists only in about half of New Orleans proper and one-quarter of the conurbation, mostly upon the higher terrain closer to the Mississippi River. The second factor is physical proximity to a neighborhood that has already gentrified, or that never economically declined in the first place, like the Garden District.

Gentrification hot-spots today may be found along the fringes of what I have (somewhat jokingly) dubbed the “white teapot,” a relatively wealthy and well-educated majority-white area shaped like a kettle (see Figure 1) in uptown New Orleans, around Audubon Park and Tulane and Loyola universities, with a curving spout along the St. Charles Avenue/Magazine Street corridor through the French Quarter and into the Faubourg Marigny and Bywater. Comparing 2000 to 2010 census data, the teapot has broadened and internally whitened, and the changes mostly involve gentrification. The process has also progressed into the Faubourg Tremé (not coincidentally the subject of the HBO drama Tremé) and up Esplanade Avenue into Mid-City, which ranks just behind Bywater as a favored spot for post-Katrina transplants. All these areas were originally urbanized on higher terrain before 1900, all have historic housing stock, and all are coterminous to some degree.

Figure 1. Hot spots (marked with red stars) of post-Katrina gentrification in New Orleans, shown with circa-2000 demographic data and a delineation of the “white teapot.” Bywater appears at right. Map and analysis by Richard Campanella.

The frontiers of gentrification are “pioneered” by certain social cohorts who settle sequentially, usually over a period of five to twenty years. The four-phase cycle often begins with—forgive my tongue-in-cheek use of vernacular stereotypes: (1) “gutter punks” (their term), young transients with troubled backgrounds who bitterly reject societal norms and settle, squatter-like, in the roughest neighborhoods bordering bohemian or tourist districts, where they busk or beg in tattered attire.

On their unshod heels come (2) hipsters, who, also fixated upon dissing the mainstream but better educated and obsessively self-aware, see these punk-infused neighborhoods as bastions of coolness.

Their presence generates a certain funky vibe that appeals to the third phase of the gentrification sequence: (3) “bourgeois bohemians,” to use David Brooks’ term. Free-spirited but well-educated and willing to strike a bargain with middle-class normalcy, this group is skillfully employed, buys old houses and lovingly restores them, engages tirelessly in civic affairs, and can reliably be found at the Saturday morning farmers’ market. Usually childless, they often convert doubles to singles, which removes rentable housing stock from the neighborhood even as property values rise and lower-class renters find themselves priced out their own neighborhoods. (Gentrification in New Orleans tends to be more house-based than in northeastern cities, where renovated industrial or commercial buildings dominate the transformation).

After the area attains full-blown “revived” status, the final cohort arrives: (4) bona fide gentry, including lawyers, doctors, moneyed retirees, and alpha-professionals from places like Manhattan or San Francisco. Real estate agents and developers are involved at every phase transition, sometimes leading, sometimes following, always profiting.

Native tenants fare the worst in the process, often finding themselves unable to afford the rising rent and facing eviction. Those who own, however, might experience a windfall, their abodes now worth ten to fifty times more than their grandparents paid. Of the four-phase process, a neighborhood like St. Roch is currently between phases 1 and 2; the Irish Channel is 3-to-4 in the blocks closer to Magazine and 2-to-3 closer to Tchoupitoulas; Bywater is swiftly moving from 2 to 3 to 4; Marigny is nearing 4; and the French Quarter is post-4.

Locavores in a Kiddie Wilderness

Tensions abound among the four cohorts. The phase-1 and -2 folks openly regret their role in paving the way for phases 3 and 4, and see themselves as sharing the victimhood of their mostly black working-class renter neighbors. Skeptical of proposed amenities such as riverfront parks or the removal of an elevated expressway, they fear such “improvements” may foretell further rent hikes and threaten their claim to edgy urban authenticity. They decry phase-3 and -4 folks through “Die Yuppie Scum” graffiti, or via pasted denunciations of Pres Kabacoff (see Figure 2), a local developer specializing in historic restoration and mixed-income public housing.

Phase-3 and -4 folks, meanwhile, look askance at the hipsters and the gutter punks, but otherwise wax ambivalent about gentrification and its effect on deep-rooted mostly African-American natives. They lament their role in ousting the very vessels of localism they came to savor, but also take pride in their spirited civic engagement and rescue of architectural treasures.

Gentrifiers seem to stew in irreconcilable philosophical disequilibrium. Fortunately, they’ve created plenty of nice spaces to stew in. Bywater in the past few years has seen the opening of nearly ten retro-chic foodie/locavore-type restaurants, two new art-loft colonies, guerrilla galleries and performance spaces on grungy St. Claude Avenue, a “healing center” affiliated with Kabacoff and his Maine-born voodoo-priestess partner, yoga studios, a vinyl records store, and a smattering of coffee shops where one can overhear conversations about bioswales, tactical urbanism, the klezmer music scene, and every conceivable permutation of “sustainability” and “resilience.”

It’s increasingly like living in a city of graduate students. Nothing wrong with that—except, what happens when they, well, graduate? Will a subsequent wave take their place? Or will the neighborhood be too pricey by then?

Bywater’s elders, families, and inter-generational households, meanwhile, have gone from the norm to the exception. Racially, the black population, which tended to be highly family-based, declined by 64 percent between 2000 and 2010, while the white population increased by 22 percent, regaining the majority status it had prior to the white flight of the 1960s-1970s. It was the Katrina disruption and the accompanying closure of schools that initially drove out the mostly black households with children, more so than gentrification per se.1 Bywater ever since has become a kiddie wilderness; the 968 youngsters who lived here in 2000 numbered only 285 in 2010. When our son was born in 2012, he was the very first post-Katrina birth on our street, the sole child on a block that had eleven when we first arrived (as category-3 types, I suppose, sans the “bohemian”) from Mississippi in 2000.2

Impact on New Orleans Culture

Many predicted that the 2005 deluge would wash away New Orleans’ sui generis character. Paradoxically, post-Katrina gentrifiers are simultaneously distinguishing and homogenizing local culture vis-à-vis American norms, depending on how one defines culture. By the humanist’s notion, the newcomers are actually breathing new life into local customs and traditions. Transplants arrive endeavoring to be a part of the epic adventure of living here; thus, through the process of self-selection, they tend to be Orleaneophilic “super-natives.” They embrace Mardi Gras enthusiastically, going so far as to form their own krewes and walking clubs (though always with irony, winking in gentle mockery at old-line uptown krewes). They celebrate the city’s culinary legacy, though their tastes generally run away from fried okra and toward “house-made beet ravioli w/ goat cheese ricotta mint stuffing” (I’m citing a chalkboard menu at a new Bywater restaurant, revealingly named Suis Generis, “Fine Dining for the People;” see Figure 2). And they are universally enamored with local music and public festivity, to the point of enrolling in second-line dancing classes and taking it upon themselves to organize jazz funerals whenever a local icon dies.

By the anthropologist’s notion, however, transplants are definitely changing New Orleans culture. They are much more secular, less fertile, more liberal, and less parochial than native-born New Orleanians. They see local conservatism as a problem calling for enlightenment rather than an opinion to be respected, and view the importation of national and global values as imperative to a sustainable and equitable recovery. Indeed, the entire scene in the new Bywater eateries—from the artisanal food on the menus to the statement art on the walls to the progressive worldview of the patrons—can be picked up and dropped seamlessly into Austin, Burlington, Portland, or Brooklyn.

Figure 2. “Fine Dining for the People:” streetscapes of gentrification in Bywater. Montage by Richard Campanella.

A Precedent and a Hobgoblin

How will this all play out? History offers a precedent. After the Louisiana Purchase in 1803, better-educated English-speaking Anglos moved in large numbers into the parochial, mostly Catholic and Francophone Creole society of New Orleans. “The Americans [are] swarming in from the northern states,” lamented one departing French official, “invading Louisiana as the holy tribes invaded the land of Canaan, [each turning] over in his mind a little plan of speculation”—sentiments that might echo those of displaced natives today.3 What resulted from the Creole/Anglo intermingling was not gentrification—the two groups lived separately—but rather a complex, gradual cultural hybridization. Native Creoles and Anglo transplants intermarried, blended their legal systems, their architectural tastes and surveying methods, their civic traditions and foodways, and to some degree their languages. What resulted was the fascinating mélange that is modern-day Louisiana.

Gentrifier culture is already hybridizing with native ways; post-Katrina transplants are opening restaurants, writing books, starting businesses and hiring natives, organizing festivals, and even running for public office, all the while introducing external ideas into local canon. What differs in the analogy is the fact that the nineteenth-century newcomers planted familial roots here and spawned multiple subsequent generations, each bringing new vitality to the city. Gentrifiers, on the other hand, usually have very low birth rates, and those few that do become parents oftentimes find themselves reluctantly departing the very inner-city neighborhoods they helped revive, for want of playmates and decent schools. By that time, exorbitant real estate precludes the next wave of dynamic twenty-somethings from moving in, and the same neighborhood that once flourished gradually grows gray, empty, and frozen in historically renovated time. Unless gentrified neighborhoods make themselves into affordable and agreeable places to raise and educate the next generation, they will morph into dour historical theme parks with price tags only aging one-percenters can afford.

Lack of age diversity and a paucity of “kiddie capital”—good local schools, playmates next door, child-friendly services—are the hobgoblins of gentrification in a historically familial city like New Orleans. Yet their impacts seem to be lost on many gentrifiers. Some earthy contingents even expresses mock disgust at the sight of baby carriages—the height of uncool—not realizing that the infant inside might represent the neighborhood’s best hope of remaining down-to-earth.

Need evidence of those impacts? Take a walk on a sunny Saturday through the lower French Quarter, the residential section of New Orleans’ original gentrified neighborhood. You will see spectacular architecture, dazzling cast-iron filigree, flowering gardens—and hardly a resident in sight, much less the next generation playing in the streets. Many of the antebellum townhouses have been subdivided into pied-à-terre condominiums vacant most of the year; others are home to peripatetic professionals or aging couples living in guarded privacy behind bolted-shut French doors. The historic streetscapes bear a museum-like stillness that would be eerie if they weren’t so beautiful.

Richard Campanella, a geographer with the Tulane School of Architecture, is the author of Bienville’s Dilemma, Geographies of New Orleans, Delta Urbanism, Lincoln in New Orleans, and other books. He may be reached through richcampanella.com, rcampane@tulane.edu, and nolacampanella on Twitter.

——–

1 The years-long displacement opened up time and space for the ensuing racial and socio-economic transformations to gain momentum, which thence increased housing prices and impeded working-class households with families from resettling, or settling anew.

2 These Census Bureau race and age figures are drawn from what most residents perceive to be the main section of Bywater, from St. Claude Avenue to the Mississippi River, and from Press Street to the Industrial Canal. Other definitions of neighborhood boundaries exist, and needless to say, each would yield differing statistics.

3 Pierre Clément de Laussat, Memoirs of My Life (Louisiana State University Press: Baton Rouge and New Orleans, 1978 translation of 1831 memoir), 103.