How we, as a nation, find bounty and beauty in the future depends upon how we react to two trends emerging from the recent difficult period in American urbanism. The first of these trends is the increasing lack of affordability in mainstream urban America, with the costs of maintaining a middle-class lifestyle at a level where distinct have/have-not lines are now drawn. The second is the increasing authoritarianism in mainstream urban America, where decisions about how our cities function are guided by a new array of authority figures that represent the common good. Both trends point to a disempowerment of a vast section of the American population.

Our loss of housing affordability is an insidious development that will continue to eat away at the urban triumphalism that marked the beginning of this century. Generation Xers, seniors on fixed incomes and the struggling middle class will have much in common during the coming decade, with fewer and fewer housing solutions designed for them. If half of our consumer goods are purchased by the top ten percent, then the rest of us are increasingly irrelevant in terms of goods, and services, as well as in housing,

Affordability on Main Street was once a concern of Wall Street. It was broadly known as Fordism, from the days when Henry Ford paid decent wages so that his workers could afford his new product, the car. Today, with Main Street on its knees, Fordism is dead and Wall Street turns more and more to itself, and to large, multinational conglomerates for profits. Volume generated by the middle class comes from a few companies like Apple, and, as the class shrinks, psychological distance between the haves and have-nots widens the gap, especially for those with memories of the material wealth they had in earlier days.

Solutions to the affordability gap in the urban realm are conspicuous by their absence. Desirable addresses, decent houses, and access to amenities are now the province of relatively few, who are serviced by those on the outside, commuting into town from less hip and trendy places. New residential housing, driven by the Wall Street investment community, is geared towards the market-rate. The linkage between mass transit and affordable housing has been deftly snipped apart by the investment community, where the topic of affordable housing generates a yawn.

Solutions? We might do well to investigate anti-urban trends, where peripheral and rural communities are stable and growing, and look at how these communities cope. Housing solutions like prefabricated units (think trailer parks, America’s answer to the favela) might be studied.

Non-affordability, as a trend, is strongly linked to a co-evolutionary partner that is driving a wedge between the haves and have-nots: an authority figure which has become a new interlocutor in of the urban conversation, a sort of urban do-gooder to save us from ourselves, pushing more requirements and accepting fewer improvisations. Affordable housing has less to do with the square footage that is in that space, and more to do with the ingredients found within the square footage.

The gloved hand of quasi-government authority has come to rest upon our cities with an increasingly tight grip, in the name of the green lobby or in the name of the traditional town.

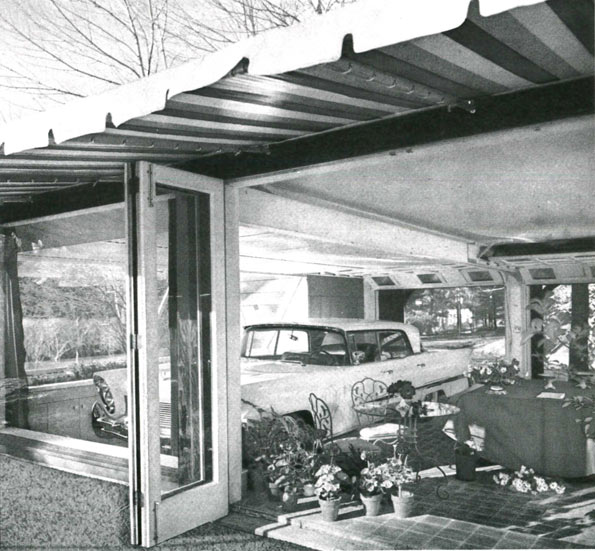

Cities underwent rapid change in the fifties and sixties due to the car, and subsequently parking garages, commercial strips, suburbs and highway overpasses sprouted. All these developments facilitated growth and expansion. Americans were remarkably unsentimental about their historic urban fabric, and notably experimental about innovative technological solutions to remove obstacles to this growth.

Today, our confidence is shaken. The rise of authorities to dictate urban form signals that the era of innovation and improvisation is over, and that American cities are entering a new era of more rigid control of what gets built. The authority, in the form of a Master Plan, treats the city as if it were a vast, private land holding, and its citizens as if they were animals in a forest that was about to be developed.

Master Plans have already been passed in Denver, Philadelphia, and Miami, and are on the boards for other cities in 2013. When a developer Master-Plans his land, he relies upon a Master to create the vision for the land, and this Master – credentialed, experienced, and hopefully talented – sets out the form of the future construction. The Master may have a passing interest in the voices from the land itself – biologists who count endangered species, for example – but the overarching form comes out of his mind, and the developer then implements the plan.

When the same process is used upon a living, dynamic city, the results vary. Future citizens, bound by the edicts of this Master Plan, may submit to the Master’s vision, or, they may chafe at its restrictions. These Master Plans are formulated with great citizen input and collaboration until the time at which they are set. After that, they are to be obeyed. The plans create a physical model, or form; they are like a glove into which the city must fit its future hand.

Master Plans attempt to take all possibilities into account, while creating ‘perfect’ rules by which the city can grow. Physical order, it is hoped, will lead to social order, as buildings once again behave like they did before the car. Should the future evolve as the Master predicts, the glove will fit the grown-up hand However, the future is notoriously difficult to predict.

The new regulatory regime has become fashionable as citizens, sickened by the dirt and ugliness of our cities, seek an authority to keep us from temptation. As such, Master Plans arise from a noble intent not unlike the one held by city planners at the turn of the 20th century: to improve urban hygiene. And they may be correct in thinking that emulating urban form as it was before the car might just bring walkability back into fashion once again.

The future, however, is ephemeral and dynamic, not static like a Master Plan, and may become frustrating to the Master Planners who have created elaborate blueprints for our nation’s cities. America’s fluid economic situation is giving rise to in-home workplaces, negating the need for traditional office space. It is giving rise to in-home manufacturing, reducing the size and complexity of factories. Warehouses, in today’s era of just-in-time-delivery, are being converted into other uses. And finally, Master Plans all seem to reminisce about Main Streets with lovely, tree-lined rows of shops under apartment (parking would be safely tucked in the back). These shops, renting for top dollar, stand empty today, made even more remote from reality with the advent of online retail.

In short, Master Plans that rigidly enforce an urban form of yesteryear may become next year’s white elephants. Cities bearing these master plans may find themselves with a regulatory burden that is reducing their desirability as places to live and work. Following these cities specifically, learning of their successes and failures, and analyzing how Master Plans are working will tell us a lot about the future.

As affordability is reduced and regulation increases, American cities could soon evolve into forms that are quite different from those of our past. And as confidence in the future fades, our cities take increasing comfort in the past, fossilizing our urban form as the Romans once did. For those underneath the affordability curve, improvisation and innovation will still continue, and insight into both of these emerging trends will yield a new sense of direction for the places where we live and work.

Richard Reep is an architect and artist who lives in Winter Park, Florida. His practice has centered around hospitality-driven mixed use, and he has contributed in various capacities to urban mixed-use projects, both nationally and internationally, for the last 25 years.

Flickr photo by alesh houdek: A walled and gated Miami home.