There are interesting developments being played out in the Rust Belt. Some cities, like Detroit, seem to be embarking whole hog down the creative class path. Others, like Pittsburgh, have their own thing going on, a thing loosely delineated as the “Rust Belt Chic” model of economic development, with no modest amount of success. How a given Rust Belt city reinvests will have a large say in its future.

Part 1 of this series examined the nascent creative classification of Detroit. Part 2 analyzes whether or not there is a new way forward for post-industrial cities, using the lessons from Pittsburgh and Cleveland as a guide.

Rust Belt Chic

Rust Belt Chic is the opposite of Creative Class Chic. The latter [is] the globalization of hip and cool. Wondering how Pittsburgh can be more like Austin is an absurd enterprise and, ultimately, counterproductive. I want to visit the Cleveland of Harvey Pekar, not the Miami of LeBron James. I can find King James World just about anywhere. Give me more Rust Belt Chic.—Jim Russell, Talent Geographer and economic development blogger at Pacific Standard.

***

Pittsburgh has been referred to as “hell with the lid taken off”. It’s not a compliment, with the moniker originating from an 1868 travelogue written in The Atlantic Monthly. But the reference is a misquote. From the piece:

On the evening of this dark day, we were conducted to the edge of the abyss, and looked over the iron railing upon the most striking spectacle we ever beheld … It is an unprofitable business, view-hunting; but if any one would enjoy a spectacle as striking as Niagara, he may do so by simply walking up a long hill to Cliff Street in Pittsburg, and looking over into — hell with the lid taken off.”

As stated, the context of the piece has been lost to the narrative of the Rust Belt malaise, with one Pittsburgh local writing: “It was practically a love letter to the city, yet that damned ‘hell with the lid taken off’ line is all that survives”.

This Rust Belt notion of “hell with the lid taken off”, “Shittsburgh”, and Cleveland as the “Mistake by the Lake” flows from a certain reality, as the post-industrial transition hasn’t exactly been a sun-bathing. But the lore is also partly contrived, since it’s derived from a stubborn stereotyping of the Rust Belt as a backwater you go to die. Such rigid yet malleable beliefs are “mesofacts”, or cognitions which—while not necessarily reflecting reality—nonetheless influence reality, particularly the act of migration. Writes Samuel Arbesman, the founder of the term:

[I]magine you are considering relocating to another city. Not recognizing the slow change in the economic fortunes of various metropolitan areas, you immediately dismiss certain cities. For example, Pittsburgh, a city in the core of the historic Rust Belt of the United States, was for a long time considered to be something of a city to avoid.

Mesofacts are an issue for Rust Belt cities. But the resultant civic booster pandering comes off as desperation, with the image makeover usually but a process to “hip” your city into something, anything else. In fact there has been ample shame in being Rust Belt. Shame for having been post-industrialized. Abandoned. Idled from what the culture is known for: hard work. The collective sense has affected how the future is plotted. Buffalo, St. Louis, Dayton yearn to be Las Vegas, Miami, Portland, New York. In fact, as we speak, Cleveland is planning a “transformational” vibrancy effort that entails hanging a Rodeo Drive-like outdoor chandelier in its theatre district. It will hang not a mile away from a neighborhood, Central, with a 70% poverty rate. Such dissonance-ensuing efforts kills recovery efforts. Said Jean de la Fontaine:

“Everyone has his faults which he continually repeats: neither fear nor shame can cure them”.

The alternative is for a city to know itself, to chart its own way. Let others copycat their way to oblivion, or to become, according urbanist Aaron Renn, some “sort of mini-Brooklyn instead of who they really are at heart”. But this isn’t easy. It requires a collective and sustained effort, and a conceptual frame that can guide the process. This, then, is the central driving tenant of Rust Belt Chic economic development. It is not a process of “kumbaya-ing”, but a strategy sourced through that basic wisdom of the ages: “Know Thyself”.

Courtesy of Red, White, and Blueprints

Below details the experiences of Pittsburgh and Cleveland using the Rust Belt Chic lens, particularly showing how an awareness of its legacy costs and legacy opportunities can be used to build emerging economies and evolving societies.

The New Economy: Neither Extraction nor Retention

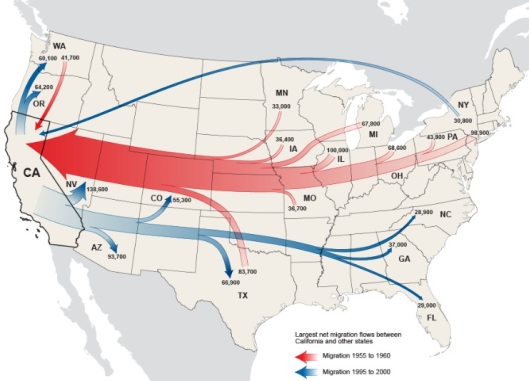

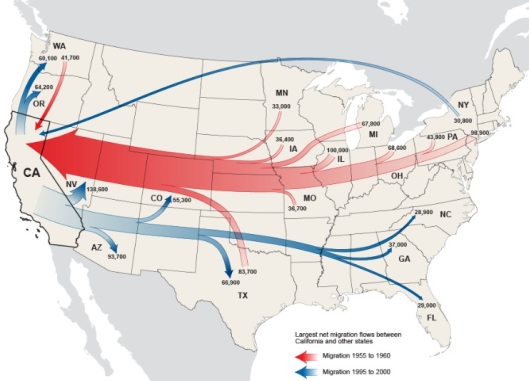

A reality for the Rust Belt is that people left. Cleveland’s population declined by one-third in the 1970s. Pittsburgh’s exodus occurred in the 1980s. In fact, the whole of the region exported people, with states like California historically benefiting. Commonly, domestic outmigration has been viewed akin to leprosy, with angst-ridden brain drain initiatives haranguing people to stay put. This is a prime example of a mesofact-driven policy that does more harm than good. Rather, understanding how to leverage the fact your citizens are everywhere would be wise in an economy where connection matters more than place. This is the view in international economic development. Rust Belt cities should get wise. How Sweden thinks:

Swedish Foreign Affairs Minister Carl Bildt believes it’s essential to embrace globalization. “I want to have more of the world in Sweden and more of Sweden in the world,” he told me. Sweden isn’t afraid of brain drain, he said. Instead, “we encourage our young people to study abroad and to work abroad.” Many return, but even those who don’t help to connect Sweden to what Mr. Bildt calls “the global flow of ideas.”

This “global flow of ideas” is not just talk. It has legs. Writes leading Rust Belt Chic thinker, and colleague, Jim Russell: “Moving from one place to another is an economic stimulus. People leaving Cleveland promotes growth.”

Courtesy of the Census.

How does this work exactly?

Think of an act of migration as a lying down of fiber optics, with each trip thickening the network between two points in space. Often, cluster relationships begin forming. Take Los Angles and Pittsburgh. For years, the best talent would be poached at Carnegie Mellon. On the surface, this meant Pittsburgh would grow the talent and California, though an employer such as Disney Labs, would reap the rewards.

Brain drain, right? Thus, spend money to herd the nerds, and make your talent inert for the sake of a Census count. Or, as Russell writes: “Pittsburgh is dying. Time to pony up the jingle and get Richard Florida to save the day.”

Well, as Ernest George Ravenstein wrote in “The Laws of Migration, 1885”, “Each main current of migration produces a compensating counter-current”, and this is exactly what happened between Pittsburgh and Los Angeles. For instance, as the cost of attracting talent into “spiky locales” started becoming prohibitive, alternatives were sought. For Disney Labs, one was locating an R&D center near Carnegie Mellon, with the decision influenced by the networks formed through by Pittsburgh’s “brain drain”. Count Google and Apple as two others bellying up in the Rust Belt backwater. As is Schell Games, an educational gaming company with a founder born in Jersey, educated in Pittsburgh, and refined in Los Angeles. Located in the South Side neighborhood of Pittsburgh, the company totaled a quarter of a billion dollars in sales in 2011. A similar process is being played out in Cleveland between Case Western, University Hospitals, and Philips Technology in the field of medical imaging. These are just some of the relational opportunities across the whole of the Rust Belt.

Digging further, there is something else going on here, particularly as it relates to the Rust Belt’s legacy asset of growing talent. To wit, other regions, like Portland, attract talent, but their educational ecosystems are less developed. The Rust Belt educates. It mines talent. Exports talent. For instance, according to the Chronicle of Higher Education, the top 10 states for out-of-state freshman enrollment reside in the Midwest (Pennsylvania is 1, Ohio is 7).

Why does this matter? Because much like the industrial epoch before it, the innovation economy—to buy a term from Economist Enrico Moretti—is converging; that is, it is becoming less “spiky” and looking for leverage. Thus, the “rise of the rest”. From the Harvard Business Review:

It goes without saying that no matter how much talent a company might have, there are many more talented people working outside its boundaries. Yet all too many companies focus solely on acquiring talent, on bringing talent inside the firm. Why not access talent wherever it resides?

The overall lesson here is this: Rust Belt cities need to get over lamenting the Chicken Little-like strategy that is plugging the brain drain. Let your people go. Let them grow. Concentrate on the network. The trend of jobs constricting its supply line to talent is likely to grow. Welcome to the “talent economy”.

“Cool” Exhaustion

Venture capitalist Brad Feld recently said, “The cities that have the most movement in and out of them are the most vibrant”. The statement speaks to the reality that Pittsburgh et al. won’t shrink their way to growth, as in-migration is needed. On that score, there’s some indication of Rust Belt demographic inflows, indicating changes of a mesofact shift.

For example, people are returning to Pittsburgh, with a positive net migration for the past five years. In fact, U-Haul’s latest annual survey marks Pittsburgh as the top growth city in the U.S. There’s some movement back to Cleveland as well. My past research for the Urban Institute showed a net inflow of 25- to 34-year olds in the city’s downtown, as well as its surrounding inner-core neighborhoods. Other Cleveland neighborhoods and inner-ring suburbs are seeing a net inflow of young adults as well. Also, migration patterns from 2005 to 2010 flowed net positive to Cleveland’s Cuyahoga County from the “spiky” counties of Chicago’s Cook County and Brooklyn’s King County.

Will the trend grow? Here, it’s necessary to infer why it is occurring, so as to emphasize the inherent competitive advantages Rust Belt cities have to offer.

Part of the psychogeographic attraction that Cleveland and Pittsburgh have is the fact they are not Portland, Brooklyn, or any other variety of venerable hot spots engaging in an arms race of mod. Industrial cities maintain distinct cultures comprised of unique histories that are manifested by both elegant and unpolished bones. In short, the Rust Belt is real places, with real people. Wrote a New York City cyclist and author on his recent trip entitled “It’s Monday, I’m Back, And Cleveland!”:

Portlanders ride around on bespoke bicycles wearing artisanal fanny packs and eating kimchi quesadillas out of food trucks. Clevelanders watch “The Deer Hunter” and eat rabbit and tubular meats while basking in the warm glow of their leg lamps…

…Cleveland has its own unique take on the whole “artisanal” phenomenon. For example, in Brooklyn people open stores where they only sell olive oil or mayonnaise, or where some Oberlin graduate will give you an old-timey shave with a straight razor and a leather strop for $75. In Cleveland, this guy sits outside his shop making bats.

Courtesy of Bike Snob NYC

Rust Belt cities, then, got their own thing going on, something at variance with the universal creative class typology said to attract “young and the restless”. To engage in copycatting would be a tragedy for Cleveland and Pittsburgh to adopt—like re-branding a flower by eroding its scent.

Joi Ito, the head of MIT’s Media Lab, agrees, saying city making is not about heavy-handed creative class endeavors, but about backing off, letting things emerge. But again, this requires city self-awareness, which, according to Ito, “has to do with the character of the city, the character of the people, the character of the mayor”. In other words, the answers for a city are inside of it. Not inside the idea of outside programming.

And by being self-aware, Cleveland and Pittsburgh could position themselves as places for the “cool exhausted”, or places about community, affordability, and family. Places that contain good single-family housing stock. Places with coffee shops, taverns, and backyards. Places not prone to the dichotomy of micro-apartments v. McMansions but rather rest in a middle-grounding sweet spot that is projected to be attractive to the next generation of homebuyers. Says a newcomer to Pittsburgh from Brooklyn:

Moving to Lawrenceville was one of the smartest things we’ve done. It’s a visually, historically, and socially stimulating neighborhood with a stronger sense of community than I’ve experienced anywhere else.

No doubt, in-migration of all types is needed—i.e., Pittsburgh’s and Cleveland’s foreign-born rates are at historic lows— but the low-hanging fruit is Rust Belt refugees, or “boomerangers”, many Global City graduates. Russell, who has been examining the phenomenon for years, sees this variant of return migration as a potential game-changer for historically declining Rust Belt cities, particularly because it represents a counter flow to the donut hole-patterning of urban decline. “This is happening, and it’s on a scale much larger than expected,” Russell says. “We are busy catching up to a trend. The Rust Belt Chic migration is a particular form of return migration: Rust Belt suburb-to Big City-to grandpa’s neighborhood”.

Economically speaking, such migrants pack a wallop, as the act of migration is primarily an entrepreneurial act. Such is illustrated in a recent New York Times piece called “Replanting the Rust Belt”. In it, they profile Cleveland chef Jonathan Sawyer who moved back home from New York to raise his family. Yet he was also determined “to help the city transcend its Rust Belt reputation”. Once there, Sawyer “foraged for people”, eventually setting up a local food ecosystem that “connects mushroom farms, bean gardens, Italian bakeries, Amish dairies, noodle makers, butchers and the basement and backyard of his own house”.

Migrants like Sawyer are economic change agents. Pittsburgh and Cleveland need to scale them up, and then do everything they can to eliminate barriers so they can forage properly.

Bowling with Strangers

As the middle class re-enters and gentrifies inner city Rust Belt neighborhoods, consequences will arise. Still, desperate city leaders are happy with any trade-offs, as is evidenced by Detroit’s economic development czar George Jackson recent declaration that: “I’m sorry, but, I mean, bring it on [gentrification]. We can’t just be a poor city and prosper.”

Such conceptions are common in government, institutionalized even. Notes Neil Smith:

Gentrification became a systematic attempt to remake the central city, to take it back from the working class, from minorities, from homeless people, from immigrants…What began as a seemingly quaint rediscovery of the drama and edginess of the new urban “frontier” became in the 1990s broad-based market driven policy.

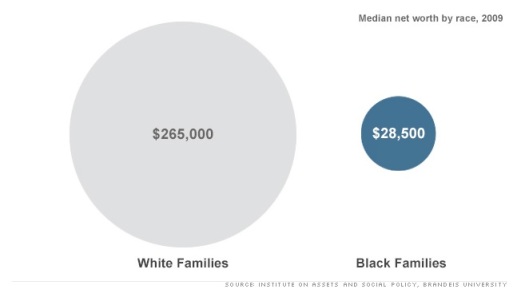

It is widely understood gentrification does little to eliminate the systemic problems facing not only the Rust Belt, but most communities: that of segregation and inequality. There needs to be a prioritizing of the underlying neighborhood dynamics that offer both hope and challenges for a path forward. To that end, given the rapidity of demographic and housing change in the industrial Midwest—i.e., it’s “brokenness”—consider the Rust Belt as good a living “lab” as any.

For instance, certain demographic shifts in various Rust Belt cities are going against longstanding patterns, particularly the organic evolution of mixed neighborhoods. The integration is coming from several angles, which is largely due to the “benefits” of a depressed housing market. For instance, in Ohio City, one of Cleveland’s gentrifying neighborhoods, the percentage of black residents increased from 24% of the population to 34% from 1990 to 2010, whereas the percentage of whites declined 58% to 50%. Given that Ohio City is one of the areas seeing an inflow of 25- to 34-year old residents, there appears to be a meet-up of lower-to-middle-income black families that have migrated from the East Side of Cleveland with younger suburban and exurban whites. The same demographic patterns are occurring in other Cleveland neighborhoods such as Edgewater, Old Brooklyn, and Kamm’s Corners, as well numerous suburbs, suggesting a “shake-up” of social capital paradigms that have kept Cleveland not only geographically segregated, but psycho-sociologically segregated.

“Social capital”, you say?

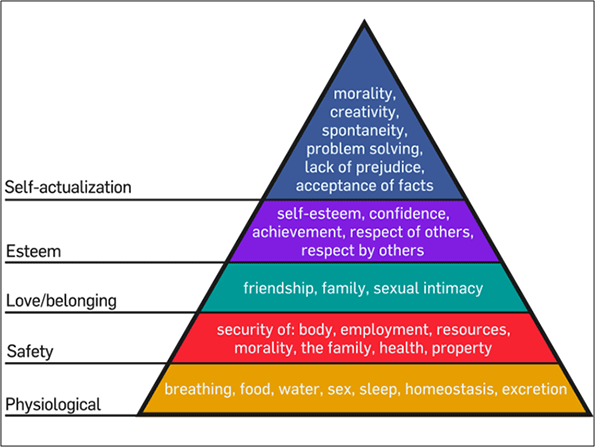

Yes. Most often social capital is talked about in good terms only, a la Putnam’s seminal book Bowling Alone But as illustrated in the paper “Why the Garden Club Couldn’t Save Youngstown”, too much social capital kills. For example, too much trust in others like you can parallel not enough trust in others unlike you, leading to immobility, insularity, and stagnation of ideas. What is needed in Cleveland and Pittsburgh is less social capital, or more movement, more outsiders, and more crossing of such psychogeographic divides as the Cuyahoga River, which has served to divide the city of Cleveland between the East and West Sides. These “shake-ups” that are occurring fosters the heterogeneity necessary to reverse Cleveland’s declining, patriarchal course.

“My Hometown”. Courtesy of Plain Dealer

But simple diversification of neighborhoods won’t do the trick. For instance, a white teen may go to a diverse high school but it doesn’t mean she will have black friends. This filtering along entrenched historical fault lines happens in neighborhoods as well. The scene in D.C.:

Both groups [whites and blacks] feel entitled and resent the other’s sense of entitlement. Over time the neighborhood’s revitalization engineers a rigid caste system eerily reminiscent of pre-1965 America. You see it in bars, churches, restaurants and bookstores. You see it in the buildings people live in and where people do their shopping. In fact, other than public space, little is shared in the neighborhood. Not resources. Not opportunities. Not the kind of social capital that is vital for social mobility. Not even words.

What is partly occurring here relates to a controversial finding of Putnam’s, or that diversity can decrease social capital—perhaps too much. “People living in ethnically diverse settings appear to ‘hunker down’”, writes Putnam, or “to pull in like a turtle”.

Why?

Part of the reason is that neighborhood diversity can equate to living “by” each other and not “with” each other. As such, neighborhood integration is still raw in the American zeitgeist, with heterogeneity, according to Putnam, engendering mistrust and too little social capital. A next step is needed. Here, community leaders should heed lessons from the concept of creative destruction. From the article “The Downside of Diversity”:

If…diversity, at least in the short run, is a liability for social connectedness, a parallel line of emerging research suggests it can be a big asset when it comes to driving productivity and innovation…

… In other words, those in more diverse communities may do more bowling alone, but the creative tensions unleashed by those differences in the workplace may vault those same places to the cutting edge of the economy and of creative culture.

This, then, represents a key opportunity for Cleveland and Pittsburgh to reconstitute a new American neighborhood model by harnessing the potential inherent in its integrating neighborhoods. This opportunity is perhaps greater in Rust Belt communities given—as of yet—the absence of housing market pressure that tends to filter people along similar demographic lines. The mission is simple: how can cities foster mobility without a complete sacrifice of trust? This entails thinking about social capital in a new way: neither a presence nor absence of it, but a continuum of social capital with insularity based on comfortability on one end, and insularity based on mistrust on the other. The sweet spot of social capital is somewhere in the middle, which entails not bowling with your buddies or bowling alone, but bowling with strangers—until they no longer aren’t.

Why is this so important?

Where people live informs them no less than where they go to school. Neighborhoods are factories of human capital. America needs to go past the gentrification model of revitalization. The cities that still have a fighting chance, like in the Rust Belt, should lead.

Richey Piiparinen is a writer and policy researcher based in Cleveland. He is co-editor of Rust Belt Chic: The Cleveland Anthology. Read more from him at his blog and at Rust Belt Chic.

Lead photo courtesy of Spicy Biscotti.