The key drivers that propelled the Reagan economy are now tapped out or out of favor.

The name of Ronald Reagan is frequently evoked by the current contenders to the GOP nomination. Donald Trump speaks admiringly of the 40th President of the United States and uses a truncated version of his 1980 campaign slogan “Let’s Make America Great Again”. Ted Cruz promises to implement Reagan’s solution of lower taxes, lower regulation and a stronger military. Before he bowed out recently, Marco Rubio was equal in his praise. And John Kasich stakes an even more tangible claim by reminding us that he is the only candidate who actually worked with Reagan.

But if Reagan’s economy is something we can reproduce, we should first understand the most important drivers of that economy. Arthur Laffer, the father of supply-side economics, said in 2006 that the four pillars of Reaganomics were sound money, low taxes, low regulation and free trade. In addition to these four, we add our own two which are more contextual enablers than proactive policies: demographics and innovation. It is our contention that the first four would not have succeeded without the last two.

Demographics: Reagan’s time in office coincided with powerful demographic tailwinds, namely a strong decline in the dependency ratio (DR), an accelerated rise in the American work force, and a rich demographic dividend. The dependency ratio (red line in the first chart below) is the ratio of dependents to workers, calculated as the sum of people aged less than 20 and over 64 divided by the number of people aged 20-64. When the US total fertility rate (TFR, the average number of children per woman) declined from 3.5 children per woman in 1960 to less than 2 in 1975, the dependency ratio followed with a lag, falling from 0.9 in 1970 to 0.76 in 1980, 0.70 in 1990 and 0.66 in 2010.

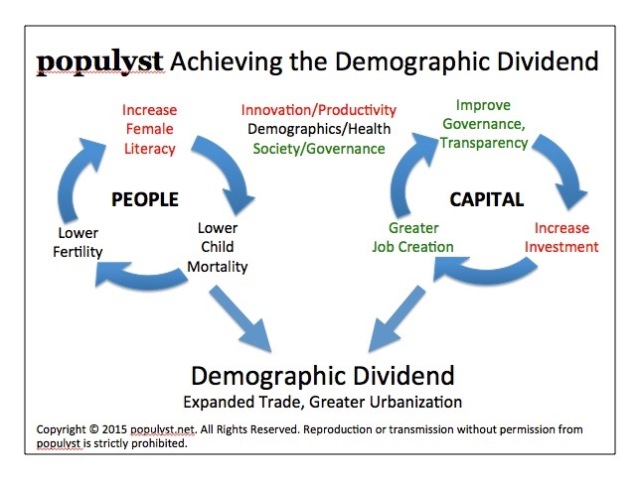

Under the right conditions when the dependency ratio falls, the economy can reap a demographic dividend. With fewer dependents, households are able to divert more of their income toward discretionary spending, savings and investments, helping create more innovative companies that in turn boost the incomes of households. That is more or less the dynamic that propelled the US economy during the 1980s and 1990s.

Looking at the future now, the dependency ratio bottomed in 2010 and is set to rise again from 0.66 in 2010 to 0.71 in 2020 to 0.83 in 2035. This increase is due mainly to the aging of the population and the increased number of dependents aged 65 or over. It is essentially a reversal of the powerful dynamic that benefited the economy in the 1980s and 1990s. The demographic tailwinds seen during the Reagan presidency have turned into headwinds.

In the second chart, we can see that the size of the US population aged 20-64 (red line) rose strongly from 1970 to 2015 and will level off and rise more slowly from here on. The population aged 30-59 (blue line), arguably the most productive and highest-earning and highest-spending segment, rose strongly starting in 1980 and flattened out around 2010. So here again, the two Reagan terms benefited from a rapid increase in the size of the work force. Clearly the most favorable period, the one with the highest acceleration, was from around 1983 to 2000, matching the economic boom of the Reagan to Clinton years.

Note in passing that a similar chart for Europe, America’s top trading partner, shows an even more troubling picture. Excluding eastern Europe and Russia (red line below), the population aged 20-64 will fall from a peak of 267 million in 2010 to an estimated 232 million in 2050. Including eastern Europe and Russia, it will fall from 459 million to 370 million.

(the charts above were derived by populyst from data produced by the UN Population Division).

Innovation: Reagan came to office at a time of great innovations in computer technology. Innovation was then and remains now one of the most potent drivers of the economy. We have every reason to hope that America will remain as innovative as it was in the past. But the rate of innovation will certainly suffer if skilled foreign professionals are unable or unwilling to come and work in the United States because of more restrictive visa or residency policies.

Interest Rates: Reagan started his first term with very high inflation and interest rates. Both started to decline during his presidency, helping stabilize and grow the economy and boosting the stock market. But we now face the risk of deflation. And interest rates are at rock bottom. As shown in the chart below from Goldman Sachs, the 10-year US Treasury yield was near 16% when Reagan took office and it is now at 2%, near all-time historic lows. Real rates are still negative and the Federal Reserve has few options left in its efforts to stimulate the economy through monetary policy.

Taxes: It is true that President Reagan enacted important tax cuts but these cuts came at a time when the marginal income tax rate was much higher than it is today. The chart below from the Tax Foundation shows that the top rate in 1980 was 70% and is now 39.6%.

The top corporate income tax rate was 46% in 1981 vs. 35% today. And the top rate for long-term capital gains was 28% vs. 20% today (plus a 3.8% Medicare tax since 2013).

Reagan’s tax cuts came at a time when spending on entitlement was relatively small compared to what it will be in the years ahead. Even at current levels of taxation, the federal budget deficit is expected to start rising again due to additional spending on old-age entitlements. The Congressional Budget Office predicts an expansion in the deficit from $439 billion in 2015 to $810 billion in 2020 and $1,226 billion in 2025. (see pages 147-149 of this CBO publication.)

And as shown in the chart below from the St. Louis Fed, the federal debt is now much higher at over 100% of GDP, vs. 31% when Reagan took office.

It seems clear therefore that there is not as much scope for cutting taxes in the current environment as there was in the early 1980s. Unless accompanied by other changes, implementation of a flat tax or general cuts in tax rates are likely to increase the debt and deficit beyond the already high projections.

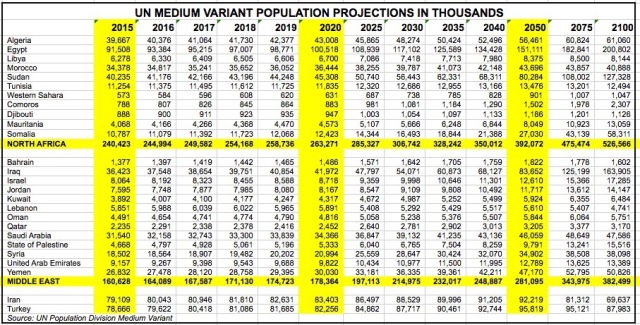

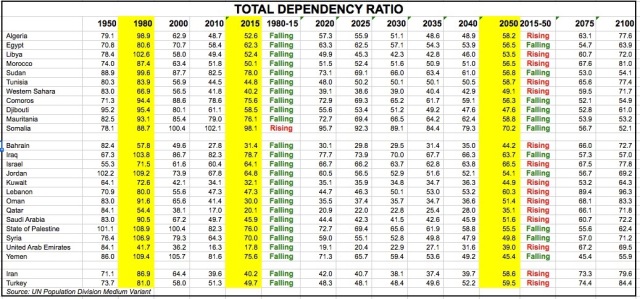

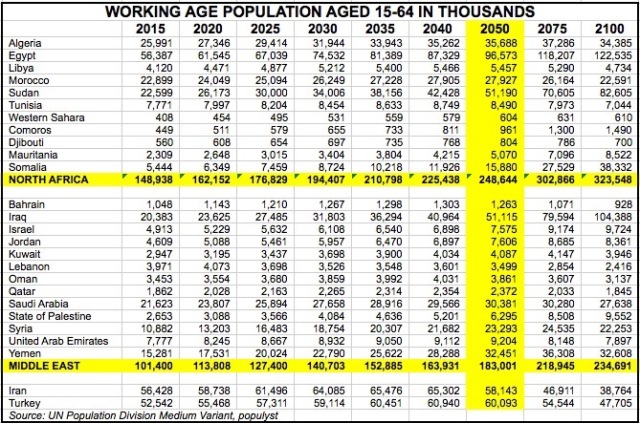

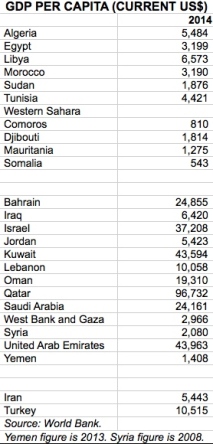

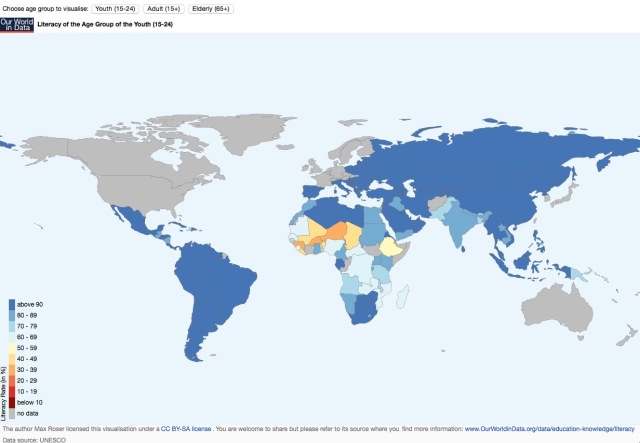

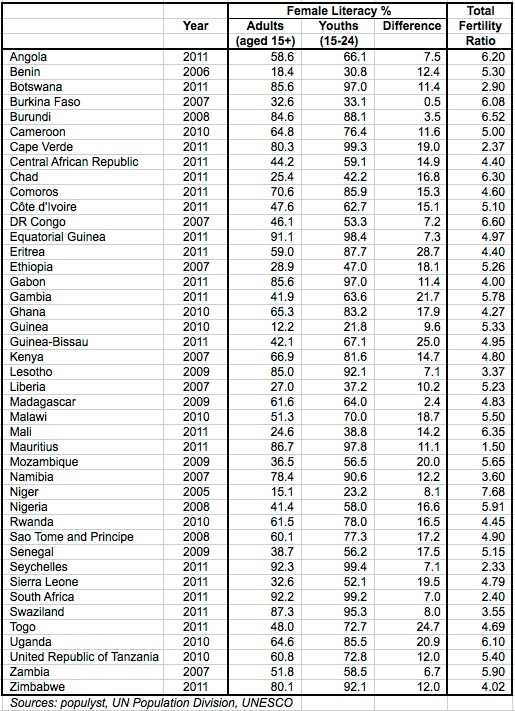

Free Trade: Opening new markets and lowering trade barriers were cornerstones of US policy in the 1980s and 1990s. If today European demand is slackening and China is entering a slower period, there could be new markets for US exports in the Asian and African frontier markets that are experiencing a demographic boom. Expanding trade to these new markets would spur new demand for American goods.

But free trade is now under attack from parties who argue that too many American jobs have gone abroad to China, Mexico and others. The presidential primaries have shown so far that a non negligible segment of the American electorate has been receptive to this argument. This means that the openness of free trade could in coming years be slowed or indeed reversed.

Adding it all up, the table summarizes the scope for success of Reaganomics today vs. in 1981.

Hoping for a replay of the Reagan years through action on the same economic levers will most likely result in disappointment. Leading 2016 candidates have expressed hostility towards free trade and have called for restrictions on all forms of immigration. In addition, the underlying context is now less conducive to growth than it was in 1981.

Nonetheless, another component of the Reagan formula was a healthy dose of optimism. Economic prospects seemed insurmountable in 1981 but the ensuing boom surpassed expectations. The US economy remains flexible and innovative and will find a way to muddle through until contextual factors improve and higher growth returns.

Sami Karam is the founder and editor of populyst.net and the creator of the populyst index™. populyst is about innovation, demography and society. Before populyst, he was the founder and manager of the Seven Global funds and a fund manager at leading asset managers in Boston and New York. In addition to a finance MBA from the Wharton School, he holds a Master’s in Civil Engineering from Cornell and a Bachelor of Architecture from UT Austin.

Photo by White House Photographic Office – National Archives and Records Administration