This essay is part of a new report from the Center for Opportunity Urbanism titled “The Texas Way of Urbanism“. Download the entire report here.

For decades, as many U.S. cities declined, and others became overly exclusive, cities in Texas evolved into places of opportunity. Due in large part to liberalized economic policies, the state’s “Big Four” metro areas — Houston, Dallas, Austin and San Antonio — consistently rank among the nation’s leaders in population growth and job growth, experiencing the rapid urbanization once common among America’s legacy cities. In a state once defined by cowboy towns, these metros have become intense human and business agglomerations, growing more global and ethnically diverse in the process.

In many ways, the newcomer to these ranks of opportunity cities is Texas’ oldest urban area, San Antonio. In recent decades, San Antonio has been considered the underdog of the foursome, able to outshine other Texas cities in professional basketball, but not in economic or cultural reputation. Houston, a mega wealthy oil town, has reached remarkable heights in health care, luxury shopping and housing development. Dallas has emerged as a mid-American banking center. Austin has become Texas’ yuppie capital, full of educated techies who are turning the city into “Silicon Hills.” But San Antonio, as America’s northernmost gateway with Mexico, has been viewed as a magnet for poor immigrants and thus a place of low incomes and education levels.

“There has been a long perception of San Antonio as a poor city with a nice river area,” says Rogelio Sáenz, dean of the public policy school at the University of Texas-San Antonio. “Even today, despite being the seventh-largest city in the country, many people outside Texas have little information about our city.”

But as I discovered while living in San Antonio for six weeks this spring, these negative stereotypes are outdated. Thanks to a commitment toward growth by the city’s political and business establishment, San Antonio in 2016 offers a much more diverse urban profile, catching up to some degree with Texas’ other major cities and surpassing many in other states.

The leading cause has been a good economy. San Antonio first grew thanks to a few key sectors, most notably its voluminous military presence, which earned it the nickname “Military City USA.” But its economy has diversified recently, seeing growth in sectors that benefit both from proximity to the military and from the broader Texas growth machine. The city’s financial industry has been propelled by providing banking for service members. The tech industry, which had overlooked San Antonio for trendier cities like Austin and San Francisco, now has a presence here; since 2010, San Antonio’s information sector has expanded by over 15 percent, placing the city 17th among the 70 largest U.S. metros in a 2016 Forbes magazine survey. The city has even seen manufacturing growth, as corporations take advantage of Texas’ corporate welfare and proximity to Mexico’s supply chains. Along with San Antonio’s more traditional economic drivers, such as health care and tourism, this expanding private sector has turned the city into a jobs engine.

And this is impelling people to move here, creating a more interesting demographic mix. The city’s historic ties to Mexico have long cemented it as the Mexican-American capital, viewed as much a part of “northern Mexico” as of the United States. It remains a majority-Hispanic city, but this, rather than being a liability, has infused San Antonio with a young, energetic population, making it a case study for how an increasingly diverse America can function. This includes “Tejanos” — native Texans of Mexican descent — and the more recent increase in Mexican nationals, professional-class immigrants escaping the violence in their homeland. Meanwhile, people throughout the U.S. seeking well-paying jobs and low living costs — including young white professionals, African Americans, Asian Americans and immigrants of every variety — are flooding into San Antonio.

This explosive job and population growth has bred all the familiar elements underpinning an urban renaissance. Indeed, just like in other rapidly growing Texas cities, there is a certain buzz about San Antonio, as it has become denser, more global and more cosmopolitan than when I previously visited in 2007. The new developments emerging in and around downtown fuel restaurants and bars that are slammed during weekends with everybody from international jet-setters to Tejano ranchers in cowboy hats. This imprint has extended to outlying areas, where new country clubs and luxury shops spring up on formerly virgin land.

Yet amid this new shine sits a more traditional culture. Just as parts of modern-day San Antonio were built during the first stirrings of civilization within Texas, the city is dominated by families who have lived here for generations, instilling a small-town, community feel. This combination of old and new — which extends across a landscape largely built by, and for, people of Mexican descent — is what makes San Antonio the most compelling of Texas’ urban success stories.

Evolution into the Mexican-American Capital

San Antonio’s Hispanic ties date to the late 1600s, when Spanish explorers mixed with the native Yanaguana population.115 The Spanish founded the city in 1718, built several missions, including the Alamo, and by 1773 made San Antonio de Bexar the capital of Spanish Texas.

By the 19th century, these religious structures were transformed into forts, as San Antonio became a prime battleground for Spain’s imperial ambitions. The city suffered from numerous battles in the early 1800s, with Spain defending its territory against ragtag armies of Anglos and natives. In 1821, Spain granted independence to Mexico,relinquishing much of modern Mexico and the U.S. Southwest, and San Antonio became the new nation’s foremost northern entryway.116 Several years later, Mexico adopted a constitution, but leaders soon violated it by forming a centralized government even more oppressive than Spain’s.

In response, many Texas towns, which were peripheral Mexican territory anyway, revolted, and San Antonio became ground zero in the Texas war for independence. This climaxed in February and March 1836, when 200 defenders encamped inside the Alamo held out nearly two weeks against a several-thousand-man Mexican militia that ultimately overwhelmed and killed them. Texas seceded soon after and became a republic, before the U.S. annexed it in 1845.

In following decades, rail connections made San Antonio an industrial crossroads. Culturally, it enjoyed influences from European and American frontiersmen and indigenous people from Mexico. By 1900, San Antonio had 53,000 residents, making it Texas’ largest city.

San Antonio’s major step forward, however, came during the Mexican revolution of 1910, an event supported by city residents. In 1876, Porfirio Diaz became Mexico’s president, overseeing a multi-decade dictatorship. In 1910, a popular dissident candidate named Francisco Madero ran for president and was imprisoned. After his family posted bail, Madero fled to San Antonio, joining other expats fomenting revolution. They organized an armed struggle that lasted for decades within Mexico, causing a refugee surge. From 1900-30, the Mexican population in the U.S. grew from 100,000 to 1.5 million, and San Antonio’s total population more than quadrupled, with refugees viewing it as a safe and culturally familiar city.

“At that time, San Antonio was the center, not Los Angeles,” T.R. Fehrenbach , a Texas-based historian, told the San Antonio Express-News in 2010. “San Antonio was the capital of the Latin American world outside of Latin America.”

Newcomers consisted largely of Mexico’s business elite. For example, the grandparents of former San Antonio mayor Henry Cisneros, and the parents of famed former local congressman Henry Gonzalez, came to San Antonio during this period. The influx of Mexican business savvy helped make San Antonio a modern city.

After slowing during the Great Depression, San Antonio resumed growth during World War II. From its inception, San Antonio was a military city, the linchpin in the defenses of Texas. This continued following statehood, as San Antonio became a prime location for military installations. Fort Sam Houston, which still sits on the city’s east side, was founded in 1845. Kelly Air Force Base opened during World War I. Other military functions would follow, and by World War II they were running on all cylinders.

The large civilian workforce that flooded into San Antonio during this time created severe labor shortages in rural areas. The federal government responded with the Bracero Program. From 1942-64, 4.6 million Mexican agricultural guest workers entered the U.S.121 Like with past Mexican migrations, many gravitated to San Antonio, and by 1970 the dusty old Spanish colonial outpost had become a 654,000 person city.

Postwar Economic Growth and Political Equality

Since then, the region has added an average of approximately 300,000 new residents per decade. Much of the influx has resulted from the organic movement between America’s colder and warmer climes. But much also stemmed from local sources and initiatives.

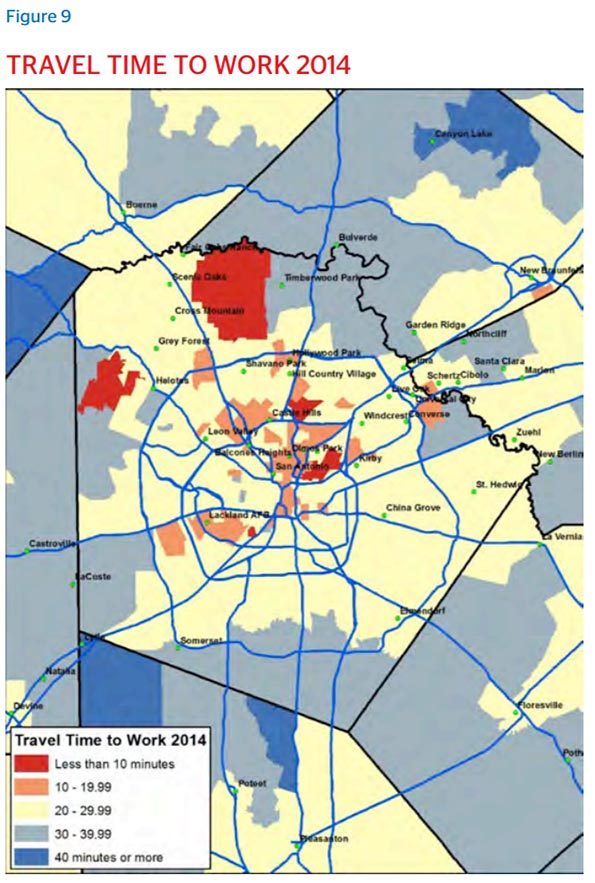

Economic growth and job creation are enhanced by transportation systems that allow people to reach employment and other destinations throughout the metropolitan area. Metro San Antonio has a highly ranked roadway system, with comparatively light traffic congestion. San Antonio ranks 10th in per-capita freeway capacity among the 53 U.S. metropolitan areas with 1-million-plus populations. This contributed to San Antonio’s ranking of 22nd best in overall traffic congestion delay among 172 urban areas in 30 nations, according to the 2015 Tom Tom Traffic Index. The metropolitan area has two freeway beltways (ring roads), like a number of other cities.

Like Texas’ other cities, San Antonio has also benefited from pro-growth state policies. Texas has no income tax and has the fifth-lowest overall state tax burden. Texas routinely ranks near the top in surveys tracking ease of doing business. Such liberalization has produced statewide in-migration of people and businesses, mostly to the major metros.

But the city’s establishment has also embraced the growth agenda. This is because San Antonio, says Cisneros, who in 1981 became the first Hispanic mayor of a large U.S. city, perceives itself as an opportunity zone for Hispanics.

“For a good part of its history, San Antonio was a poor city,” he suggests. The establishment has responded by making economic development “the central current of San Antonio’s political discourse and electoral politics … [giving] us the basis on which we decide other questions.”

This has meant, on one hand, subsidizing a number of flashy projects. San Antonio’s famed River Walk, first restored in 1941, has been serially expanded to connect key downtown tourist spots. San Antonio hosted the World’s Fair in 1968, rebranding itself as the northernmost Latin American gateway into the United States. And public money was used to retain the San Antonio Spurs, who proceeded to win five NBA titles, putting the city on the map perhaps more than anything else.

But growth has mainly occurred because local and regional officials embraced the unsexy projects needed to enhance San Antonio’s infrastructural footprint. For example, the city pumps water from the vast Edwards Aquifer that spans central Texas. Thus San Antonio has more reliable water access — and cheaper water rates — than other cities, who rely on surface-level infrastructure and are more subject to droughts.

In the 1970s, San Antonio joined its municipal energy company — CPS Energy — with a south Texas regional nuclear power network. Unlike other cities that joined, CPS entered the partnership to generate its own power, rather than renting it from a third party, making it the nation’s largest city-owned utility for gas and electricity. This has helped the company eradicate the middle man, selling energy to San Antonio residents and businesses at 10 percent to 20 percent less than in Dallas and Houston.

Another area has been key to San Antonio’s political development and the rise of Hispanics. From 1955-75, San Antonio’s City Council was controlled by the Good Government League, a mostly white group that endorsed pro-business candidates. The group fought patronage politics, but was exclusionary in nature. In the early 1970s, San Antonio became ground zero for La Raza Unida, a national movement dedicated to increasing Hispanic representation within government. Working against the GGL, the movement organized voter drives throughout the early 1970s, and by 1977 had helped inspire council elections by district, rather than at-large. This meant that following the 1977 election, the majority-minority city had filled five of 10 council seats with Hispanics and another seat with an African American. This diversity at City Hall has continued.

But, according to Michael Cary, a writer for the San Antonio Current, the political establishment has still championed the pro-growth leanings of the GGL, thus merging two constituencies that otherwise remain divided. This merger was embodied by Cisneros, who was elected to council in 1975 and later served four terms as mayor.

“Cisneros broke with the liberal Chicano ranks and ran on the West Side Good Government League ticket,” wrote Cary, serving “as a bridge between Anglos and Hispanics.”

The former mayor agreed that this unity remains intact, thanks to the citywide “political consensus” favoring growth.

“We’re not going to do it with welfare, we’re not going to do it with income maintenance, we’re not going to do it remaining contentious and divided,” Cisneros said, summarizing the Latino and Anglo establishments’ attitudes. “We’re going to do it if we come around a single theme — jobs.”

Diversifying Economy

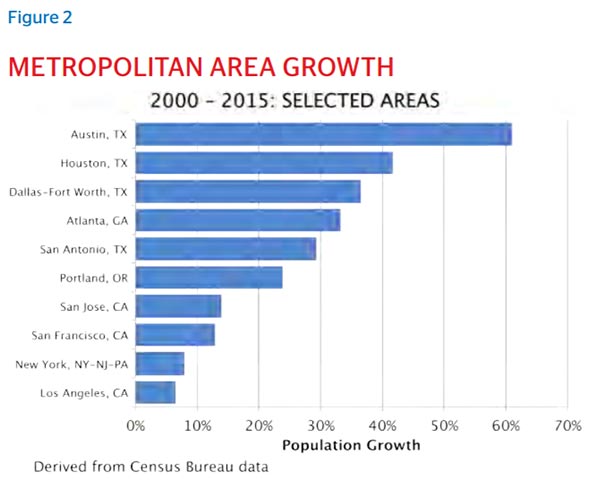

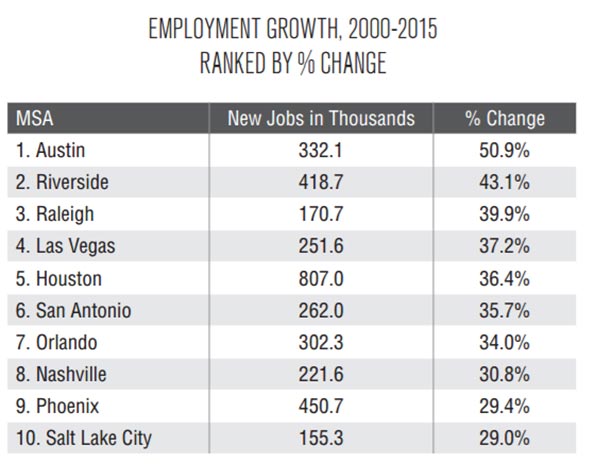

This approach has powered San Antonio near the top on various growth and prosperity metrics. Since 2000, San Antonio has been No. 8 among the 50 major U.S. metro areas in population growth rate.

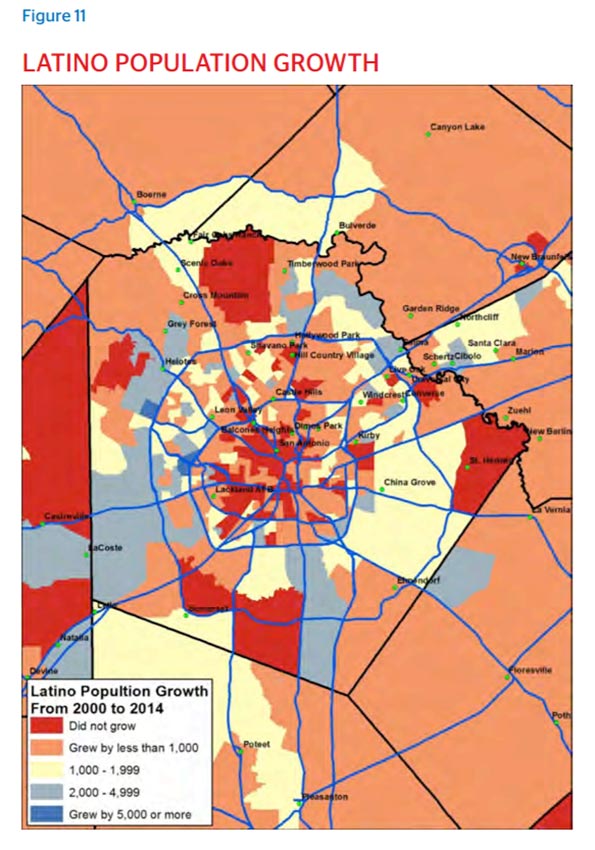

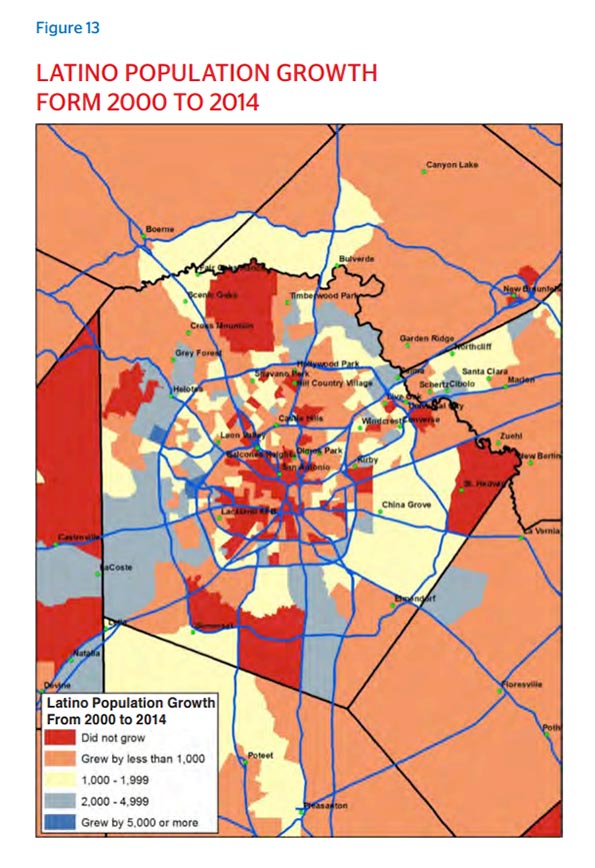

Critically, this growth has been due largely to Latinos. Since 2000, the area has been among the leaders in net Hispanic population growth, adding over 400,000 residents. Economic prosperity explains much about why people are coming. Over this time, San Antonio has been No. 6 in job growth rate among these metros, and the highest income growth among major metropolitan areas since 2005, according to Forbes magazine. When comparing Hispanic populations in the 53 largest metros, San Antonio has been one of only four to see median household income gains since 2000 and has the 15th-highest median household income for Hispanics when adjusted for living costs. According to the Kauffman Foundation, San Antonio is No.10 in startup activity, and the area unemployment rate is nearly two percentage points below the national average. The Milken Institute ranked San Antonio No. 12 among its best-performing major metros, although it has ranked higher in previous years.

The backbone of this growth is an economy that has strengthened and diversified. In 2011, Mario Hernandez, former CEO of the San Antonio Economic Development Foundation, wrote about how San Antonio was evolving beyond its “big three” industry sectors — tourism, military and health care. His points have only strengthened since.

Among the original big three, military remains the strongest. According to a study by the city government, San Antonio “is home to more Department of Defense students and active runways than any other military installation.” The metro area also includes 55,000 military retirees. The military has a $27.7 billion economic impact and employs 189,148 people. Lackland Air Force Base and Fort Sam Houston are by far the area’s largest employers, at 37,000 and 32,000 workers, respectively, while other significant installations include Randolph Air Force Base and Camp Bullis (the names of all four begin with the moniker “Joint Base San Antonio”). There is also a special relationship between the military and the city’s Hispanics, who have historically viewed military service as an opportunity for well-paying jobs, free educations and integration into mainstream American society.

Bioscience and health care is another vast sector, having grown from $12 billion to $30.6 billion in annual economic impact since 2003.136 The industry employs 164,000, or one of six San Antonians.137 In many ways, the sector is an outgrowth of the military, as medical workers receive training for — and often operate on — personnel preparing for, or returning from, battle. Following the federal Base Realignment and Closure Commission’s report in 2005, many of the Pentagon’s medical functions were concentrated in San Antonio, infusing billions of dollars into the city. This was highlighted by the new Medical Education and Training Campus built at Fort Sam Houston, the world’s largest facility for military medical education, research and training. The center’s students often apply their knowledge at nearby Camp Bullis, a site that specializes in combat training. Just down the block within Fort Sam Houston, meanwhile, is Brooke Army Medical Center, an inpatient hospital that is the military’s largest health care organization.

Yet the military’s medical functions only scratch the surface of San Antonio’s health care sector, with much of the private and nonprofit institutions located on the northwest side. The city benefits from the South Texas Medical Center, the Baptist, Methodist and University Health Systems, the University of Texas Health Science Center, the Children’s Hospital of San Antonio, and numerous other hospitals, research labs and medical startups.

Tourism has been the city’s third economic staple, employing one in eight San Antonians. This is centered on traditional attractions like the Alamo and the River Walk, and outlying lures like Six Flags and SeaWorld. The impact will surely expand, because last year San Antonio’s five former Spanish missions were given UNESCO World Heritage status.

Aside from the big three economic drivers, San Antonio is expanding into manufacturing, aviation, finance, technology and education, all tied somewhat to the military. While not traditionally a manufacturing city, San Antonio is now Texas’ fourth-largest manufacturing market, with the industry accounting for 57,000 jobs. One notable coup came when San Antonio, thriving on the corporate relocation momentum throughout Texas, compelled Toyota to build its largest manufacturing plant on the city’s south side in 2003. There was a combination of factors involved — the state offered $133 million in corporate welfare; the city government made infrastructure upgrades; local entrepreneurs stepped up to create a supply chain; and the city is proximate to the strong truck-buying markets in Texas and Mexico. As The Rivard Report, a local news website, noted 10 years later, “the company’s total direct investment in the plant has reached $2.1 billion, with $1.5 billion or more invested by the supplier community.”

The aviation industry, an offshoot of both the military and manufacturing, has also grown exponentially in recent decades. Key to this has been Port San Antonio. In 1995, following the Cold War’s end, Kelly Air Force Base was closed. A government entity was created to repair and lease out the vast space to private companies, and the port has become a profitable facility, avoiding the graft and waste endemic in other American ports. Port San Antonio, which is located not near water but near heavily trafficked I-35, is dedicated to heavy industrial and aerospace uses and includes tenants like Boeing, Lockheed Martin and StandardAero, although it also houses cybersecurity and IT companies.

The military has also brought growth to San Antonio’s financial industry, specifically through the rise of niche companies that loan to military members, who are traditionally seen as higher risk. The granddaddy of them all is USAA, a Fortune 500 firm headquartered in northwest San Antonio that employs 17,000. Significant mainstream banking institutions include JP Morgan Chase, which employs 5,000 locals, and Frost Bank, based in San Antonio. By year’s end, the latter company will break ground on a new 23-story downtown headquarters.

The military has driven tech growth, as well. Some of this $10 billion impact is generated by federal agencies that contract with local IT and cybersecurity firms, making San Antonio No. 2 in the country in concentration of data centers. Much of the rest comes from a more subdued private startup scene, which has benefited from the city establishment’s focus on tech, and the energy of one man, city native Graham Weston. In 1998, Weston co-founded Rackspace, a cloud computing company in northeastern San Antonio that employs 3,300 and is valued at $3.29 billion. Weston has since made it his mission to grow a tech scene downtown, renting out incubator space and filling it with small organizations that collaborate on ideas, including Weston Urban, the 80/20 Foundation, Geekdom, Techstars and Tech Bloc.

Lastly, the military — and San Antonio’s wider network of STEM enterprises — is inspiring educational growth. While San Antonio has historically enjoyed several small, renowned liberal arts schools, it more recently strengthened its public higher education. A University of Texas branch opened in 1969, and a Texas A&M branch followed in 2009. UT San Antonio, has an enrollment of 28,000. Its cyber security program is ranked first in the nation by tech industry professionals, meaning that graduates can plug into the region’s tech and military scene. The local community college system, Alamo Colleges, has partnered with Port San Antonio to establish workforce development programs, and the general focus for its roughly 60,000 students is on aerospace, manufacturing and IT.

One industry in San Antonio that has not been particularly strong — likely to the benefit of the others — is local government. In many major U.S. cities, the largest employers are some combination of city governments, county governments and various civil service authorities. In San Antonio, the city government is the ninth-largest employer at 9,145.

But perhaps the biggest economic driver has been population growth itself, with the city proper adding 325,000, and the metro area growing by 673,000 since 2000, creating a greater demand for housing, cars, services and food. San Antonio’s most inspiring private-sector story provides a window into that growing consumption. The region’s largest private employer, at 20,000 people, is H-E-B, a San Antonio-headquartered supermarket chain. Founded in 1905 by Florence Butt, who opened a small shop in nearby Kerrville, it has skyrocketed under her grandson Charles’ leadership, largely by remaining based in one of America’s consistently fastest-growing states. H-E-B has 316 stores in Texas and 52 in Mexico, and is one of America’s most highly

valued companies, at $22 billion.

Demographic Momentum

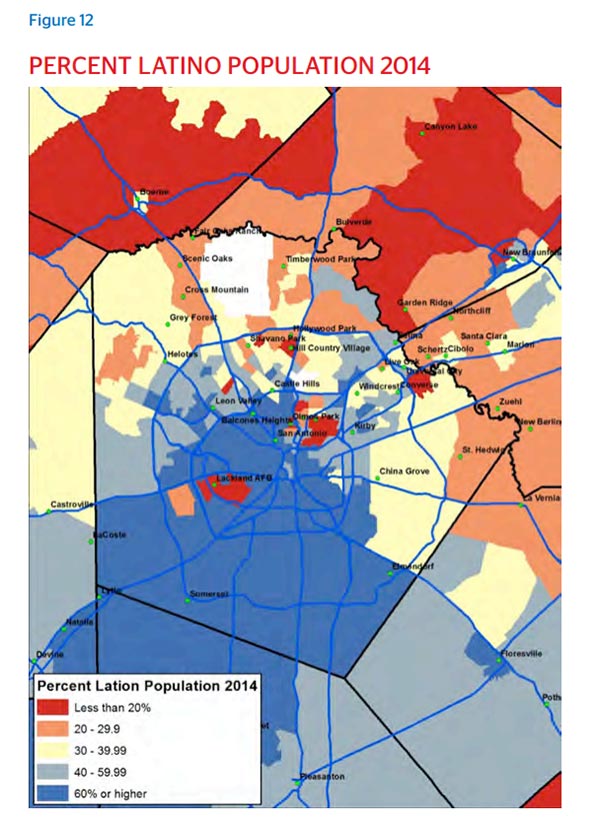

So which groups are driving this population increase? The San Antonio area , at 63.2 percent, is the most Hispanic major MSA in the country, well ahead of Miami MSA at 43.8 percent. San Antonio’s Hispanic population largely consists of Tejanos, a south Texas term describing native Texans of Mexican descent. According to Pew Research Center data, 89.6 percent of San Antonio’s Hispanic population is Mexican. This is the largest share among Texas’ Big Four cities. But, notably, San Antonio has by far the lowest percentage of Hispanics who were foreign-born. While the share of foreign-born Hispanics is 32.4 percent in Austin and around 45 percent in Houston and Dallas — not to mention 42 percent in Los Angeles and New York City, 54 percent in Washington, D.C., and 66 percent in Miami — it is only 17 percent in San Antonio. This is because many of them have lived in San Antonio for generations.

Additional Mexican-American influxes originate from Texas border towns like Laredo, Brownsville, McAllen, and other parts of the Rio Grande Valley. Tejanos have traditionally viewed San Antonio as a destination for jobs, education and entertainment. At the same time, the city is a short drive from their families. This proximity is important, explains Stephanie Reyes, a public-affairs staffer at the San Antonio Chamber of Commerce and a Brownsville native.

“In most Hispanic cultures, [families] want you to stick around, they want to see you grow, especially if there’s that possibility of you raising a family elsewhere that they’re not going to get to take part in, seeing them grow up or seeing them every weekend. Here in San Antonio, [south Texas Tejanos] have that opportunity.”

Nonetheless, there is still a lot of Mexican immigration into San Antonio, although the profile has changed. The stereotypical Mexican entering the city postwar was the poor agricultural worker. More recently, San Antonio has seen an explosion of professional-class Mexican migrants from major cities like Monterrey, five hours south on I-35. This group’s wealth has made them targets for kidnappings in their homeland. So they have moved to the U.S., with over 50,000, according to a Los Angeles Times report, coming to San Antonio, thanks to its proximity and ingrained Mexican culture. They have worked in white-collar professions and inhabited north-side gated communities, becoming known for lavish consumption. This is evident on any weekend in the upscale north-side mall of La Cantera, where parking lots are jammed with luxury cars and the walkways with Spanish-speaking shoppers in designer clothing.

Javier Paredes, a local architect who grew up in Morelia, Mexico, epitomizes some of these trends. Eight years ago, his mother, an influential mining broker, was kidnapped and forced to reveal company secrets. After her release, the family settled together near downtown San Antonio, because of the city’s cultural familiarity.

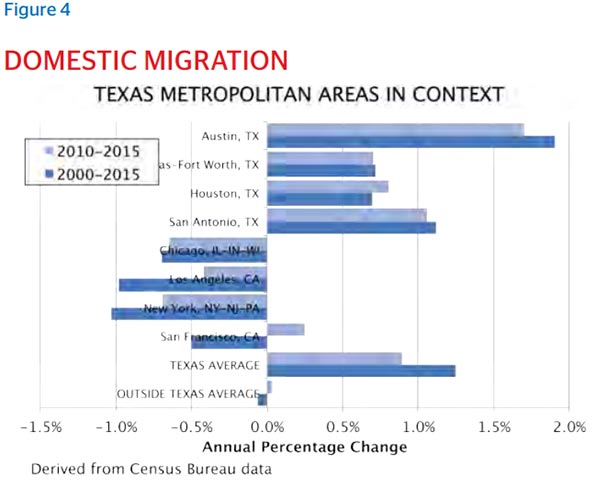

There has also been substantial in-migration from many races and places throughout America. San Antonio has become, like the other Texas cities, a major lure for domestic migrants. This is in stark contrast with major ocean coastal cities such as New York, Los Angeles and Chicago.

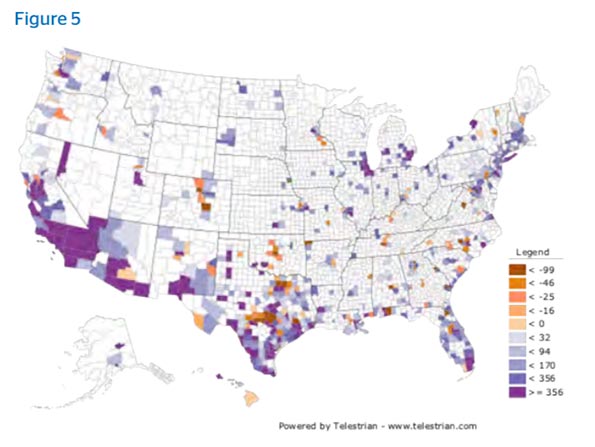

This domestic growth was displayed in a map by Manhattan Institute senior fellow Aaron Renn, showing which parts of America people net are leaving for San Antonio. There are only a handful of areas that had positive net migration from San Antonio, most notably Austin, 80 miles to the northeast. Meanwhile, whole swaths of the country — including much of California, Cascadia, Florida, the Southwest, the Northeast and the Rust Belt — are pushing people out and into San Antonio.

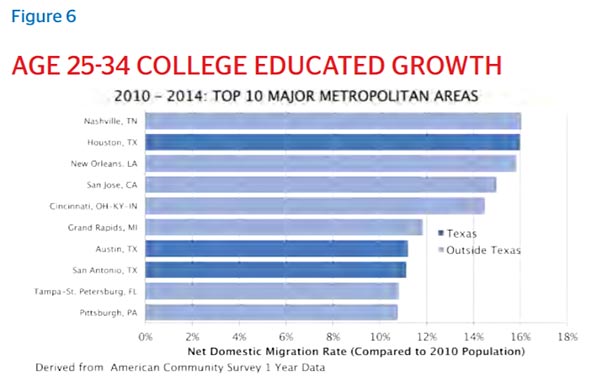

This is particularly true for the young. Once an area that had trouble holding onto younger educated people, the region has now emerged as one of the fastest-growing destinations for them, outpacing in terms of growth such traditional “brain gain” centers as New York City, Boston and San Francisco. From 2010-13, San Antonio had the second-highest percentage growth among college-educated persons ages 25-34, and the fastest growth rates over that period for 20-to-29–year-olds of all education levels.

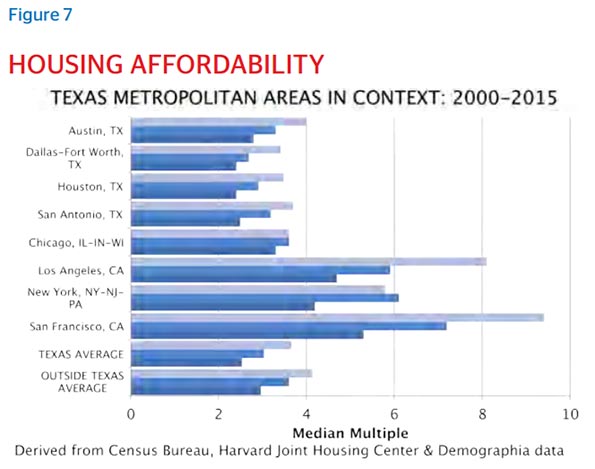

The reasons are multifaceted: Some people may be seeking warmer weather, better amenities or a historical setting. More likely, migrants are drawn to San Antonio for pragmatic reasons. The cost of living is relatively low, highlighted by median home prices that, at $131,000, are $55,000 below the national median. San Antonio also has strong employment opportunities and companies desperate to hire, explaining the wage growth.

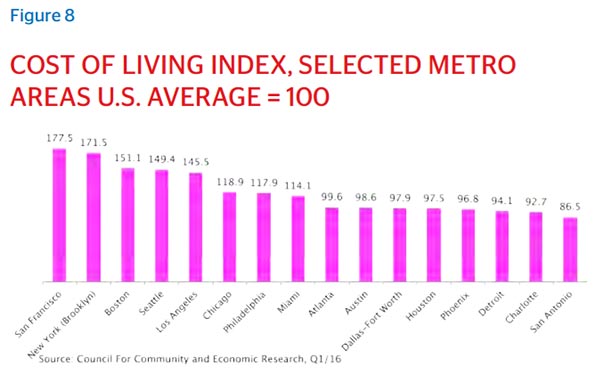

These low housing prices explain much of San Antonio’s relatively low cost of living. According to the Council For Community and Economic Research, San Antonio’s living costs are less than half those of New York or San Francisco, and considerably less even than sunbelt boom towns such as Houston, Dallas-Ft. Worth, Austin, and Phoenix.

“We don’t have enough people,” says Tony Quesada, editor-in-chief of the San Antonio Business Journal, “so we wind up importing talent from other parts of the country.”

Then there are quality-of-life factors: Average one-way commute times are several minutes below the U.S. average, at 22 minutes. And, once drivers get off the city’s highways, they will likely be strolling through any number of quiet, secluded neighborhoods.

But complementing these factors is an attraction that you hear repeatedly during interviews and will find anecdotally while navigating the streets — “comfort.” San Antonio is a big city with a small-town feel, where people are friendly, and community relations are tight. This was reaffirmed in July, when Travel + Leisure magazine named San Antonio America’s Friendliest City, based on reader surveys.

Former mayor Cisneros called this dynamic the city’s “secret sauce,” claiming that it has helped unify whites and Hispanics, as well as competing factions of the business and political communities. The sentiment was echoed by outsiders, including 31-year-old real estate developer Juan Cano. By his mid-twenties, he’d grown frustrated with San Diego’s traffic, high costs and mediocre job market. So he studied what city he should relocate to, and, after combining several economic and quality-of-life factors, chose San Antonio.

He said the best thing he’s encountered in his seven years here is the city’s homey atmosphere.

“What San Antonio beats people out on is not weather, is not number of activities or amenities; but what they beat out other cities and states on is congeniality,” he said. “People here really care about how your day is going.”

Cano agrees with Cisneros that this openness also bolsters the business climate, including for small entrepreneurs like him, looking to make connections.

Formation of a New Kind of City

Of course, growth doesn’t occur in a bubble; when various factors drive lots of people into an area, there will be tangible changes at street level. A traditional urban commentator might guess that such growth would produce infill densification, as it did for the coastal cities that boomed during America’s industrial era.

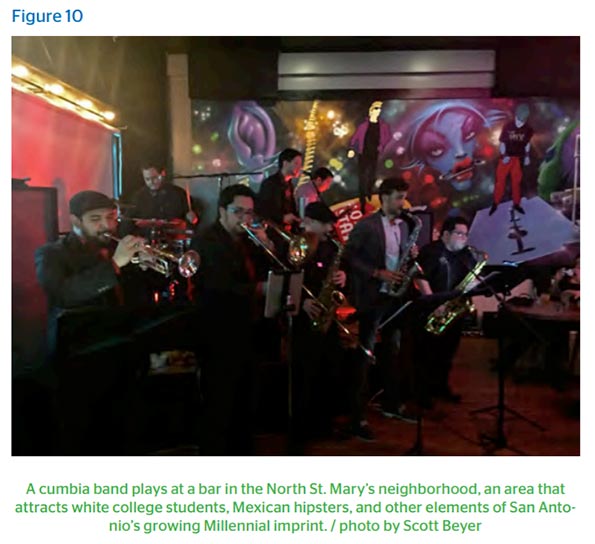

And to some degree, such “buzz” is now felt in Texas’ opportunity cities, including San Antonio. While its downtown remains largely for tourists, adjacent areas are growing more vibrant and cultured, thanks to millennial population growth and city-funded enhancements. The River Walk has been extended north and south of downtown, sparking mid- and high-rise development. Along the “Southtown” portion of the route, new condos mix with historic homes and mostly unpretentious nightlife. Along the route’s northern portion, the city pursued a public-private partnership to create the Pearl District, a mixed-use, master-planned development that has become one of America’s leading warehouse revitalization stories. Other interior neighborhoods — North St. Mary’s, Tobin Hill and the Market Square area in west downtown — are slowly filling in.

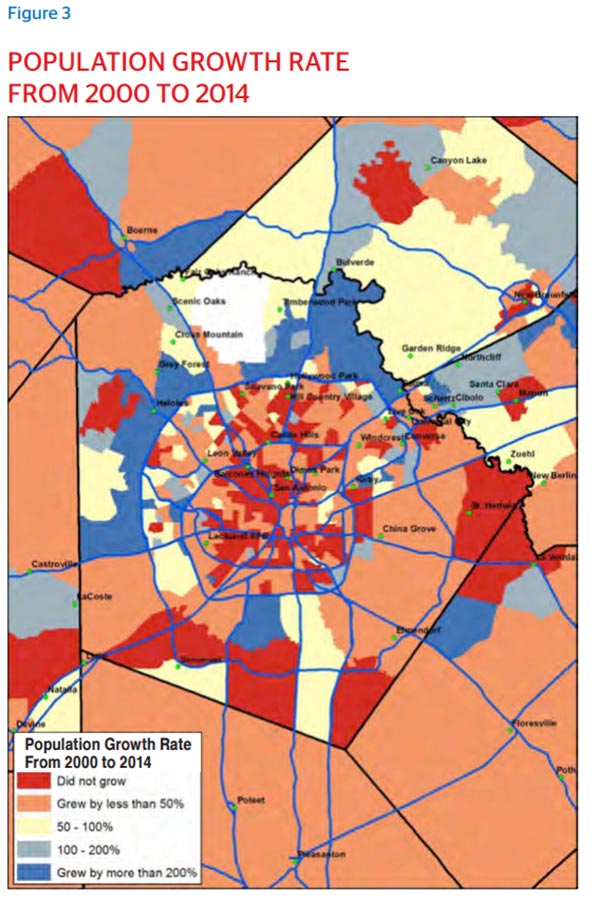

But if San Antonio is showing some welcome growth in its inner ring, the city’s trajectory continues further outward, primarily to the north. This section of town long was the exclusive white area, while lower-income Mexican-American families dominated the west and south sides, and African Americans the east side. This segregated pattern still defines San Antonio, although things are changing.

Stone Oak is the prototypical example: Once a stretch of undeveloped Texas Hill Country extending north from the state Highway 1604 loop circling the central city, it has become a gargantuan master-planned community of 31,000 residents in just two decades.159 It features densely packed single- and multifamily housing and retail rolling for miles.

Stone Oak accommodates much of San Antonio’s new money, which is to say that it is one-third Hispanic. The community is populated by health workers, techies, staffers at nearby UTSA and most notably, Mexican nationals.

Growth is even occurring in the historically hyper exclusive suburbs carved out within San Antonio’s city boundaries, like Alamo Heights and Terrell Hills. According to Sáenz, these areas were once forbidden to minorities. Today, there is a Hispanic presence in both suburbs, and generally throughout San Antonio’s north side. This suggests that the city is providing upward mobility for large portions of its Hispanic population.

Future Challenges

Cities that enjoyed the rapid growth now experienced by San Antonio have also suffered the downsides. New York, San Francisco and Los Angeles, among others, are economically dynamic and culturally interesting, yet overwhelmed by overloaded infrastructure, service failures, growth-killing regulations and patronage-ridden political machines that only worsen these problems. When I asked community leaders how San Antonio could avoid this fate in coming decades, two answers surfaced.

The first was that San Antonio needed to continue expanding infrastructure, a point emphasized by local billionaire and Spurs owner Red McCombs. This could mean everything from doubling down on housing and highway construction to exploring 21st-century solutions like green energy. While there have been recent expansions, the San Antonio-Austin corridor lacks a top-notch airport, which may explain why neither city has had the same success attracting corporations as had Houston and Dallas. In other cases, however, the city is taking the initiative in infrastructure growth. In May, the San Antonio Water System board approved the takeover of the Vista Ridge Pipeline, a new project that will diversify the water supply. San Antonio also recently launched SA2020, a plan designed to improve the city on 58 quality-of-life indicators.

Fortunately, San Antonio is in a financial position for such expansion; while other U.S. cities’ pension debts have prevented them from even providing well-paved streets. San Antonio has among the lowest per capita unfunded pension liabilities of any major city. For six consecutive years, the city has received a perfect bond rating. It also has a population, said McCombs, while overlooking the downtown skyline from his north-central office, that understands intuitively the connection between capital investment and prosperity.

“You give Texans a good reason for paying taxes,” he said, “and they’ll pay them.”

Secondly and perhaps even more critically, San Antonio needs to continue mobilizing its minority population, mainly by improving its K-12 education system. While there are countless success stories here, there are also Mexican-Americans and African Americans who have lived in multigenerational poverty on the city’s west, south and east sides, and low-skilled, non-English-speaking immigrants are still arriving. Many of their neighborhoods, while certainly nicer than most urban American slums, are nonetheless rundown and have lower-performing public schools than those in outlying areas. The city and the state have taken several recent measures to address the problem, including a city voter-approved sales tax increase for Pre-K schooling, and charter school expansion.

Other K-12 measures have been more innovative. The SA Works program, for example, is a partnership between the city and the Chamber of Commerce to connect high school and college students with local companies and other supporting agencies, who then offer internships and job-shadowing opportunities.

In June, a partnership was launched between the San Antonio Independent School District and H.E.B. to open five specialty schools that will plug students into the local employment scene.

If San Antonio continues embracing new ideas to address its infrastructure and education challenges, it will remain a regional growth engine, and an example for other cities. America, after all, is slated to become 23 percent Hispanic by 2035. San Antonio represents an extreme early version of this demographic shift, and an example of how it can work.

“San Antonio,” concluded Cisneros, is “driven by the understanding that jobs and incomes are the way we’re going to progress, and, in fact, we have. I see it in the quality of restaurants, the [more diverse] crowd at the Spurs [games], in the retail mix of the city, the integration in neighborhoods, with Latinos and African Americans moving into neighborhoods once beyond their reach. Intermarriage. It’s almost as if a new culture has emerged. … It’s one culture adapting the things that it likes about another culture.”

These same economic and cultural improvements can be observed in other big Texas cities, suggesting that they are the outcome of liberalized polices. San Antonio, as the Mexican-American capital, has long been the underdog of the four great Texas cities. But today its Latino character is proving to be yet another asset, contributing a unique wrinkle within Texas’ broader urban growth story.

Scott Beyer is a Forbes columnist and cross-country traveler who covers U.S. urban issues. For three years, he’s circling America to live for a month each in 30 cities, starting from Miami and ending in New York City. The point is to write a book about revitalizing cities through Market Urbanism — which is the intersection of classical liberal economics with urban issues. But he also writes articles on multiple other city subjects.

Top photo: Zereshk [GFDL, CC-BY-SA-3.0 or CC BY 2.5], via Wikimedia Commons