Reihan Salam, often an insightful critic, argues in Salon that poverty has come to the suburbs at a higher rate than it has grown in big cities because poorer service workers have followed the service jobs required in the suburbs. This has caused problems. Salam sees more civil strife in suburbs like Ferguson, Missouri today partly because the different kinds of family structures that have become so predominant, particularly those exhibited by the poor, cannot be accommodated in single-family, detached housing.

There’s clearly some truth here but overall the policies he suggests do not hold water. Households led by singles are up to over 20 percent of all households in the most highly populated metropolitan areas, two-parent families with the manpower to take care of suburban homes and lawns has fallen, and single parent households have grown. His solution: to build smaller, high-density attached housing units, not so much because they are more affordable for the poor; many of the suburban poor already live in rental housing units, and overall high density is generally more expensive than lower density. Salam sees density and its concomitant higher property assessments as generating more tax revenue, thus reducing local government aggressiveness in levying traffic and loitering fines (administered mostly through an often distrusted police force), which have grown to become an enormous burden for the poor in the suburbs.

But Salam doesn’t seem to appreciate that much of the desperation for local tax dollars is driven by increases in the number of residents — all kinds of residents but including the poor — and especially the young and poor, who generate the demand for expensive services like schools, special education, and law enforcement. Salam is under the impression that higher density buildings produce more property tax revenue, but he doesn’t acknowledge that if these buildings are filled with more people per acre than a single family home, they will also require more services, and generate the need for more taxes. One of the enduring political features of high-density urban areas is the lack of a tax base (or political willingness) to adequately fund big city school systems. By court order, New York State had to revamp its school aid formula in the early 2000s to channel billions in more funds to the New York City public school system, which State Supreme Court Justice Leland DeGrasse ruled had for years neglected its constitutional obligation to ensure "the availability of a sound basic education to all children of the state."

In fairness, one of the most perplexing issues in urban planning over the decades has been whether or not certain types of housing pay more or less in property taxes than their inhabitants require in government services. This question has not been answered to anyone’s satisfaction.

There are broader questions raised by this article. If the poor (the majority of whom are single mothers) are poor at least in some respect to there being only one or no working adults in a household, wouldn’t a poor, single mother of three still be poor living in an attached apartment (as opposed to a basement of a single-family home)? If at least one social objective to alleviate poverty is to create two-income households, it is not clear how building smaller housing units would encourage this. As the University of Washington’s Richard Morrill and others have repeatedly shown, our most densely populated areas (i.e. those with smaller housing units) exhibit the most severe forms of economic stratification.

Nor is it clear how Salam’s recommendation would address the aspirations of the poor, most of whom still seek one day to acquire a piece of property and a single-family home. A recent Redfin study found that 92 percent of “Millenials” (those born during the early 1980s and now in their late 20s and 30s) who don’t own a home want to buy one in the future. And according to figures from the 2008 Current Population Survey, as reported by Thomas Tseng in Newgeography.com, 44 percent of Millenials belong to some racial or ethnic category other than "non-Hispanic white." It’s an unfortunate reality of American life that even into the second decade of the 21st century a disproportionate number of the poor are racial minorities. One must assume that a goodly portion of these young aspirants to homeownership must be poor racial minorities.

How would forcibly filling the landscape with apartment buildings and crowding out single-family, detached homes (making them, therefore, more expensive) help the poor achieve that dream?

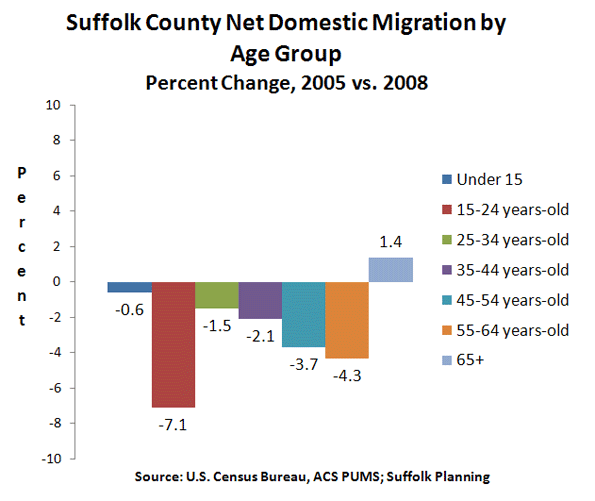

Salam’s remedy of building smaller living units might even exacerbate another problem that some suburbs (and the nation as a whole) face: the “birth dearth”, or the decline, especially in older suburbs, of family formation and birth rates. As opposed to the “nursery” for America’s next generation that many of America’s sprawl suburbs still remain, urban centers today are among the most “child free” ‑ whether in Manhattan, San Francisco, Chicago, or Boston. But even in the old-line suburbs, since the 2008 recession, the number of new children has plummeted. The largest declines in the 5 to 14 cohort since 2000 have almost all occurred in the large coastal metropolitan regions, including their suburbs, led by Los Angeles where the child population has dropped by 303,000, or 15.3%, since 2000. In the New York metro area, the number of 5- to 14-year-olds has fallen by 238,000. This includes the Nassau-Suffolk region, America’s “oldest suburb,” which has experienced a decline of 71,834 residents in the 0-14 population group between 2000 and 2013.

Today the number of households with children is 38 million, about the same as a decade ago, even as the total number of households has shot up by nearly 10 million. There are now more houses with dogs than houses with children.

The decline in the numbers of potential young suburban residents suggests not some great urban revival, but a drain in the population of future taxpayers and workers. As demographer Wendell Cox and others have shown, localities with higher densities have considerably lower birth rates than areas with lower densities. With the push for higher density, are the suburbs slated next to become “child free zones”?

Few would dispute that many suburban areas across the country lack sufficient housing options. But the seemingly ubiquitous assumption that high density housing will eradicate problems such as high taxes, increasing inequality, civil unrest, and lower birth rates may be invested with an unjustified sense of certainty.

Seth Forman, Ph.D, AICP, is author of American Obsession: Race and Conflict in the Age of Obama and Blacks in the Jewish Mind: A Crisis of Liberalism, among other books. His work has appeared in publications that include National Review, Frontpagemag.com, The Weekly Standard, and The American. He is currently Research Associate Professor at Stony Brook University, and the Chief Planner for the Long Island Regional Planning Council. His opinions are not associated with any of these institutions. He blogs at www.mrformansplanet.com.