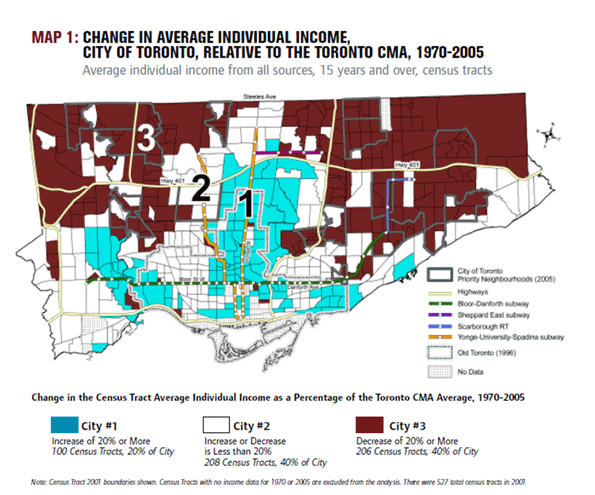

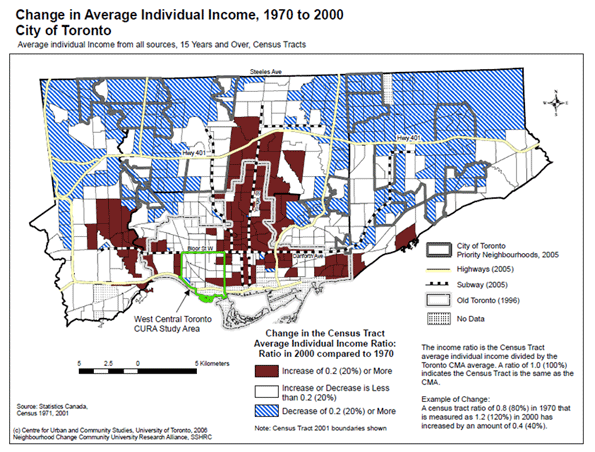

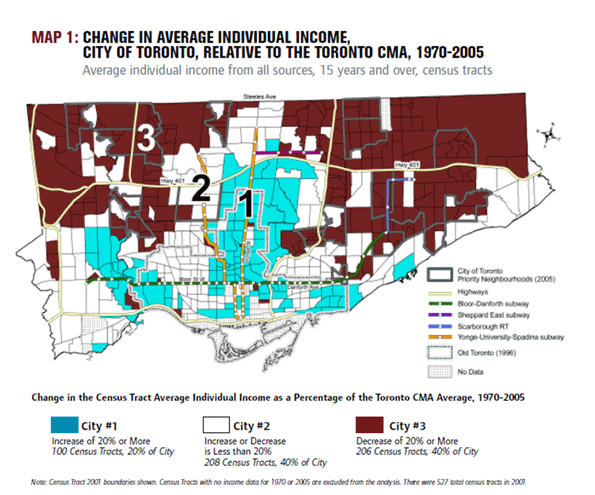

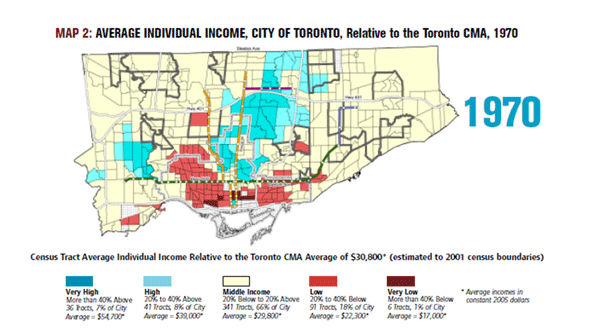

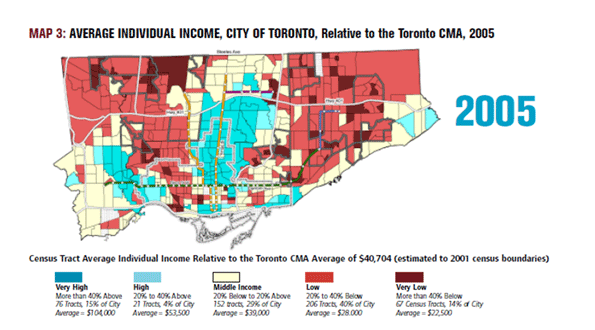

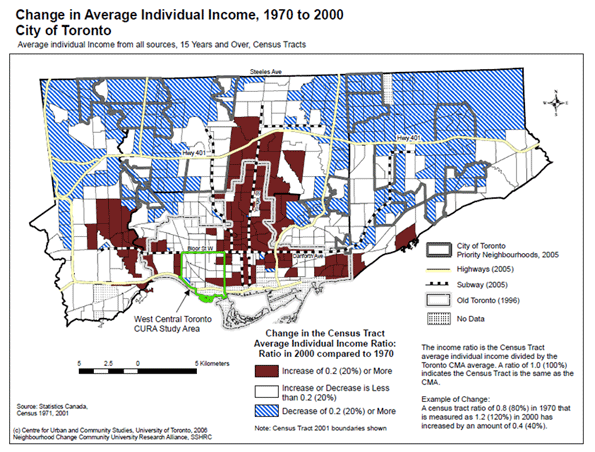

The issue of income disparity in Toronto has once again been brought into the public eye by a December 15th report by University of Toronto Professor David Hulchanski. The report, “The Three Cities Within Toronto,” points to a growing disparity in incomes between Downtown Toronto, the inner suburbs, and the outer suburbs of the city. The report demonstrates that between 1970 and 2005 the residents of the once prosperous outer suburbs have been losing ground compared to the now wealthy downtown core. The results for the inner suburbs have been mixed.

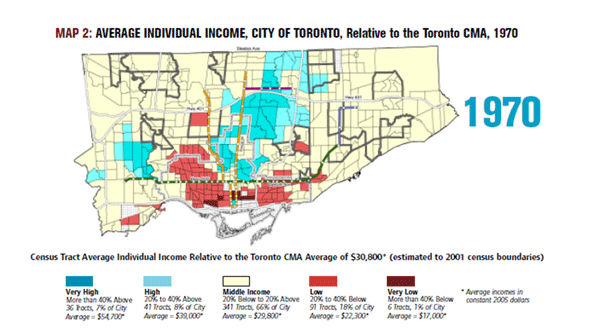

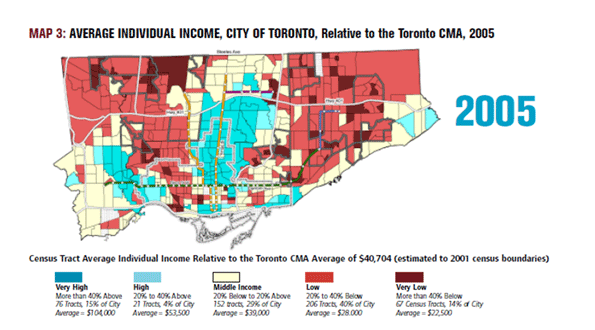

In 1970, 66% of city neighbourhoods were considered middle income. Only 15% were considered high or very high, and 19% were low or very low. In 2005, only 29% of neighbourhoods were considered middle income. The number of high or very high income neighbourhoods rose to 19%, while low and very low income neighbourhoods made up a staggering 54% of neighbourhoods.

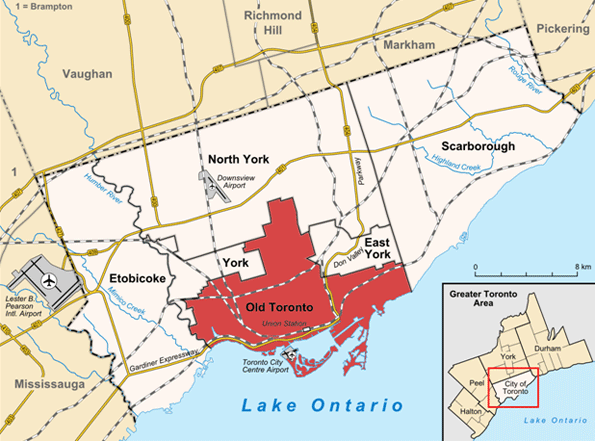

The news isn’t all bad. After all, the downtown core is now one of the most desirable places to live in North America, and many of the formerly low income neighbourhoods have gentrified, or are in the process of doing so. However, many of the city’s traditional suburbs have been decimated. The former cities of Etobicoke and Scarborough used to be middle class. Not so much anymore.

In real dollar terms, even the majority of the very low income areas have become wealthier. The trouble with poverty statistics is that they focus on relative poverty, rather than absolute poverty. This means that if Etobicoke’s average income doubled tomorrow, the downtown core would all of a sudden be considered poor. This is a major limitation. Toronto isn’t exactly turning into a Canadian Detroit.

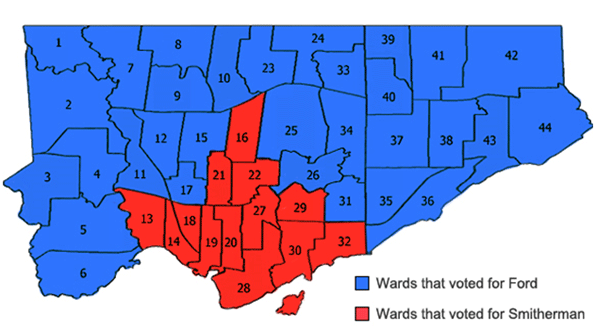

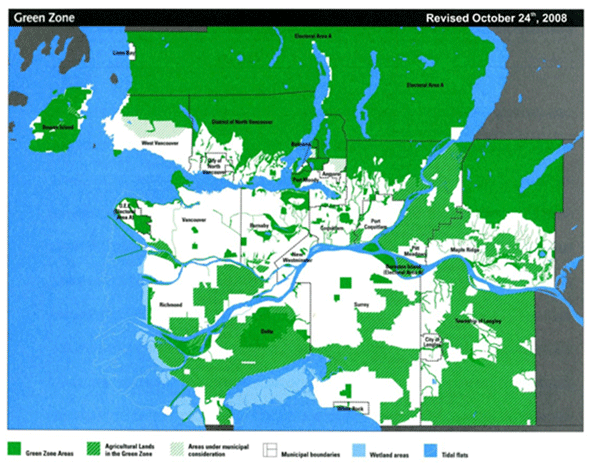

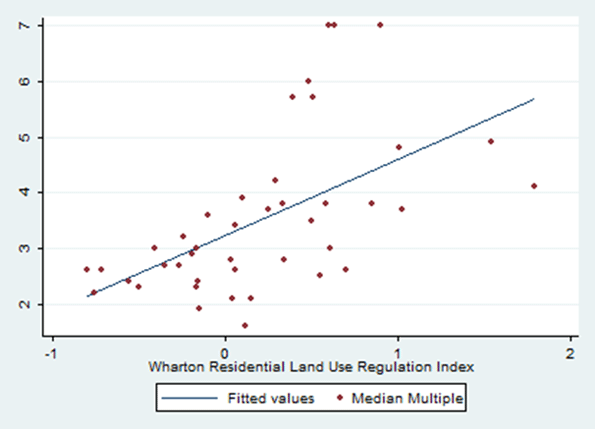

The report rightly points to the need for greater mobility in the outer suburbs. Given that the most lucrative jobs are typically downtown, many young professionals and recent graduates living outside of the core need to be able to get downtown cheaply and quickly in order to build their careers. Where the report goes wrong is that it recommends stricter land use regulations, stronger rent controls, and the revival of the flawed Transit City plan that Mayor Ford vigorously campaigned against in the recent election.

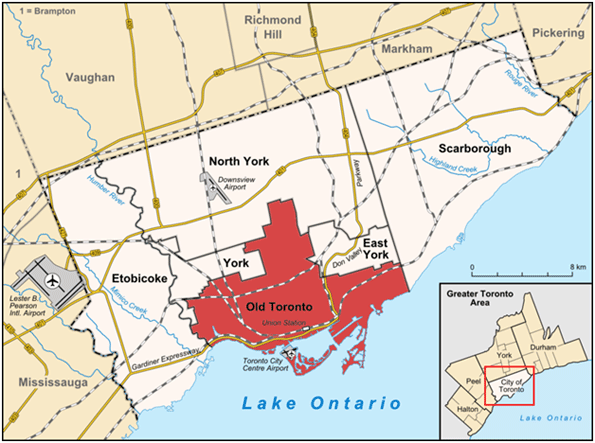

It is easy for academics to blame a lack of social welfare spending, or suburbanization for the problem. The real problem is the loss of local policy making power resulting from amalgamation. For the most part, the areas losing ground the fastest are the formerly middle class suburbs amalgamated into the city. In contrast the “exurbs” just outside of city boundaries have thrived. This is no coincidence. The real takeaway from this study is that the suburbs have different needs than the central core. By attempting to accommodate the needs of both, the megacity has benefitted neither. Short of de-amalgamation, the only hope for the city is to substantially decentralize policy making. No amount of spending can make up for the loss of local autonomy.

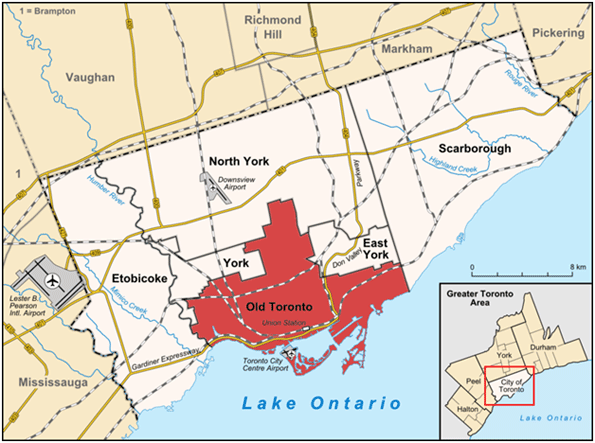

Policies have different effects in different types of cities. Take the treatment of automobiles. It might make sense to discourage automobile usage in downtown Toronto, but the benefits of doing so in Vaughan or Pickering would be questionable at best. Similarly, mandating that every commercial establishment have a public washroom probably makes sense as a public health measure in downtown, where public urination is an issue, but not so much in suburban Markham, or Richmond Hill.

Making sensible regulations for a small, relatively homogenous area isn’t all that difficult. Applying these regulations to a large, demographically diverse area can help some areas and hurt others. It’s not that regulations need to be a zero sum game. People in Etobicoke wouldn’t be affected if, say, maximum parking allotments were tightened in the downtown core. They would be affected if they were tightened throughout the entire megacity. Similarly, increasing maximum parking allotments might hurt the core and help the suburbs. The current one size fits all approach sometimes benefits the core and sometimes benefits the suburbs, but ever both.

Perhaps more important than city wide regulations is the centralization of taxing power. Since the merger, the city now sets tax rates across the entire megacity. This also allows the city to control the ratio of residential to non-residential taxes. The city of Toronto has the highest ratio of non-residential to residential taxes in Ontario. This means that businesses carry a higher share of the tax load in the city than anywhere else in the province. The combination of tax and regulatory policies in the city have lead the Canadian Federation of Independent Businesses to rank Toronto as the second least business friendly city in Canada. On a scale of 1-100, Toronto came in at 33, slightly ahead of Vancouver’s 31. Meanwhile, the rest of the (Greater Toronto Area) GTA is near the top, at 61. Neighbouring Oshawa took the top spot in Ontario with 69.

|

GTA Area Cities by CFIB Entrepreneurial Cities Policy Score

|

|

Rank (Ontario)

|

City

|

Score

|

Driving Distance to Yonge and Bloor

|

|

1

|

Oshawa

|

69

|

0:45

|

|

6

|

GTA (Excluding Toronto)

|

61

|

|

| |

Mississauga

|

61

|

0:27

|

| |

Brampton

|

61

|

0:41

|

| |

Richmond Hill

|

61

|

0:32

|

| |

Markham

|

61

|

0:32

|

| |

Vaughan

|

61

|

0:32

|

|

16

|

Hamilton

|

55

|

0:58

|

|

19

|

Guelph

|

54

|

1:15

|

|

24

|

Barrie

|

52

|

1:16

|

|

27

|

Brantford

|

51

|

1:20

|

|

30

|

Kitchener

|

48

|

1:23

|

|

33

|

Toronto

|

33

|

|

| |

Etobicoke

|

33

|

0:20

|

| |

Scarborough

|

33

|

0:21

|

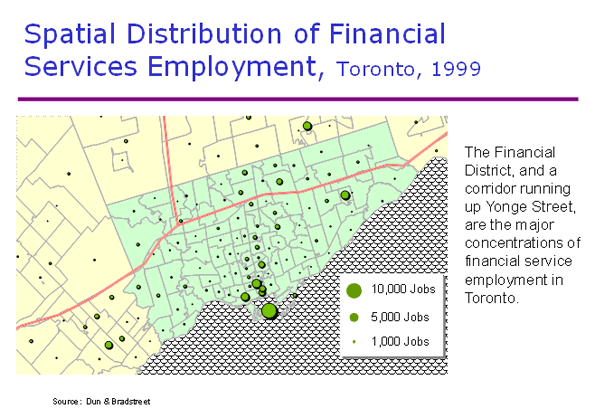

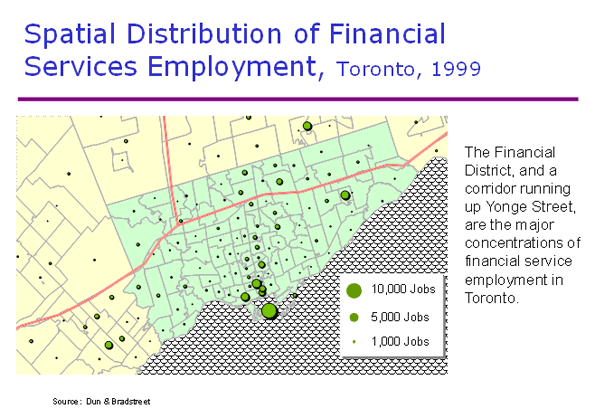

Now the share of non-residential to residential taxes in Toronto may actually make sense downtown. The core is home to the third biggest financial sector in North America. These jobs are heavily concentrated in the downtown core.

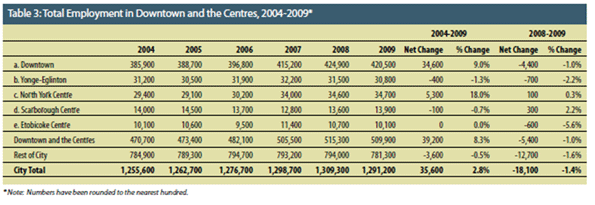

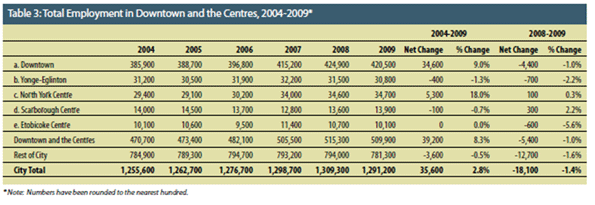

Downtown Toronto isn’t competing with low tax Vaughan or Barrie for these jobs. They are competing with high tax cities like New York and Chicago. This means that employment in the core is not as easily chased off by taxes and regulations than in the suburbs. But in industries like wholesale and manufacturing, which are far more important outside of the core, employment can easily relocate to Barrie, Mississauga, Oshawa, and so forth. Indeed, jobs have been leaving the city since before the recession hit.

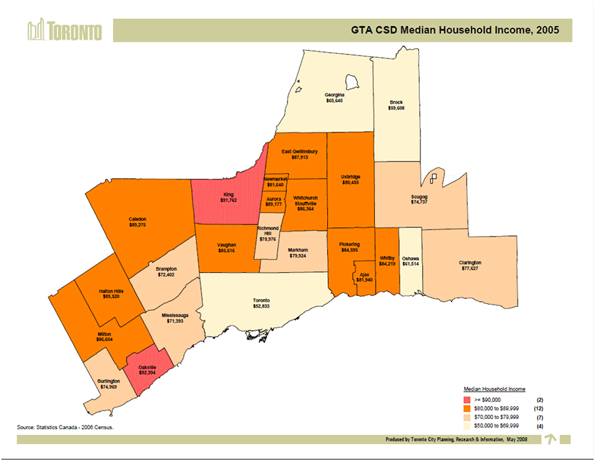

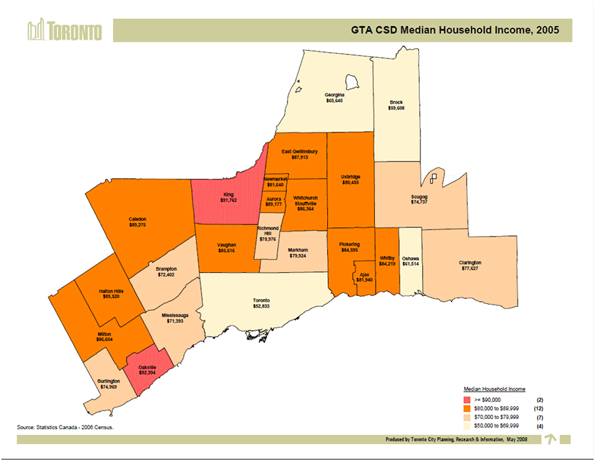

Since 2004 Downtown and North York have prospered but the rest of the city has lost jobs. This should make the results of the Professor Hulchanski’s report unsurprising. The financial sector isn’t enough to keep the entire city employed or lift wages in the city-controlled suburban rings. As a a result despite the thriving financial sector, Toronto was dead last in the GTA in terms of median incomes.

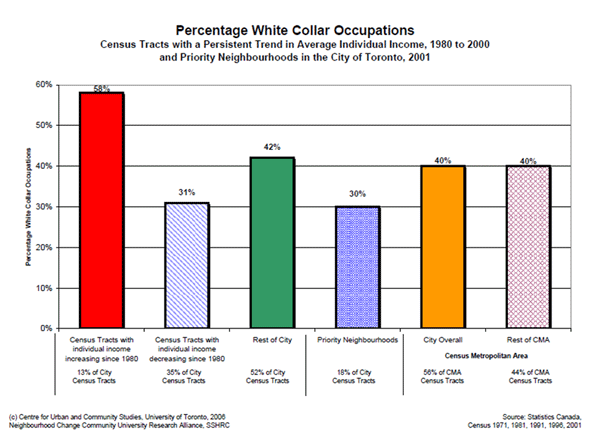

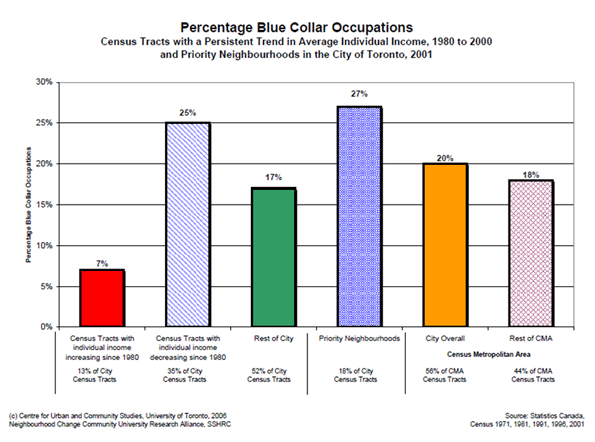

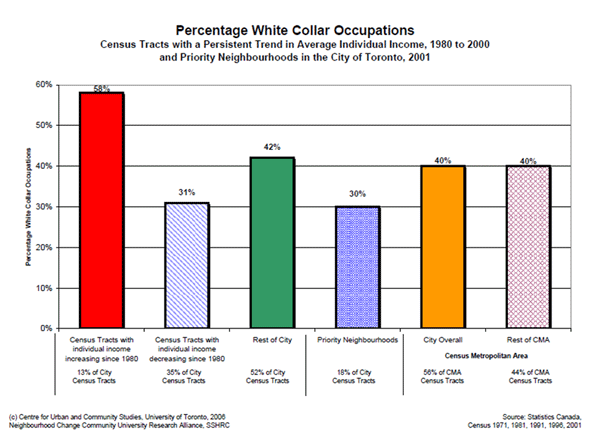

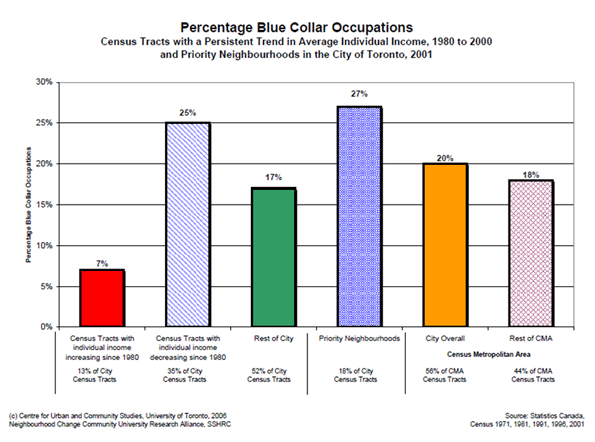

To turn this around, the city must decentralize decision making power so the suburban communities can come up with their own economic development strategies. No matter how much the city improves transit to the outer suburbs, they will not be able to significantly increase median incomes without creating more jobs. The financial sector will continue to grow, but many of jobs created in this sector require specialized training, and thus go to people from outside of the city. This doesn’t do much for former manufacturing workers in Scarborough and Etobicoke. Growth of the financial sector combined with the dispearance of blue collar jobs together guarantee continuing income disparities in the city.

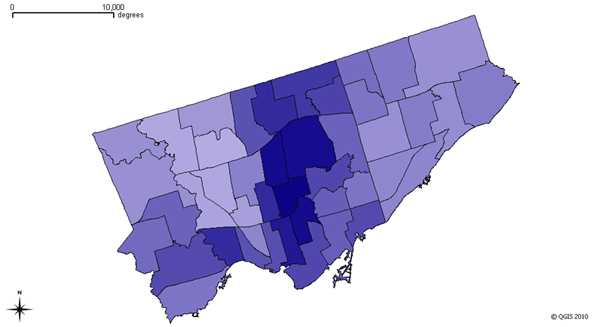

Below is previously published data from Professor Hulchanski that highlights how badly blue collar sections of the city have been hit.

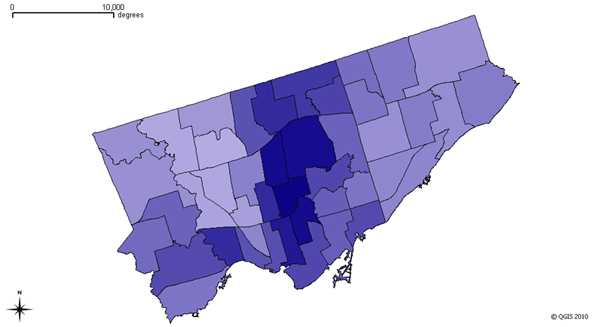

Fundamentally, a strong focus on financial and other so-called “creative class” jobs will do little for these areas. The above map was created by Richard Florida’s Martin Prosperity Institute. It shows that most creative class jobs are clustered around the subway, but this doesn’t mean that expanding rail transit will expand creative class employment. Building a light rail line through a neighbourhood doesn’t suddenly transform the residents into artists and physicians. It may attract more artists and physicians, but this could actually hurt local residents by driving up rent and property values without creating jobs for them. Below is a map of educational attainment by ward. The darker the colour, the higher the number of residents with a bachelor’s degree or higher.

The real problem is that a focus on elite jobs creates exactly the kind of bifurcation that progressive complain about. Given that city wide business policies are tailored towards creative class type occupations, it is unlikely that price sensitive manufacturers will find any reason to locate within city boundaries, rather than setting up shop in Mississauga or Barrie.

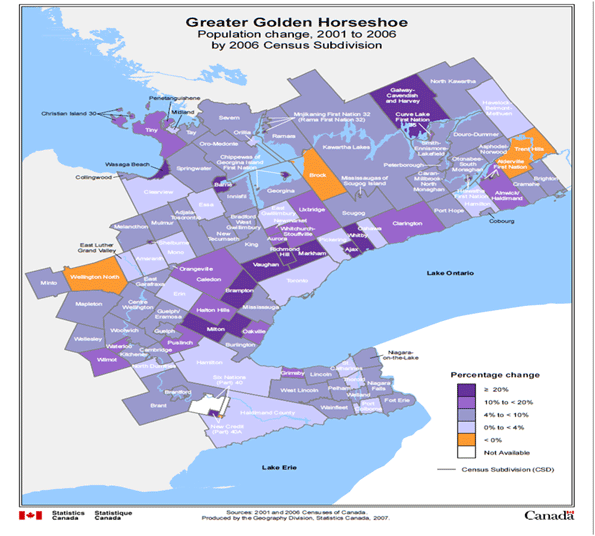

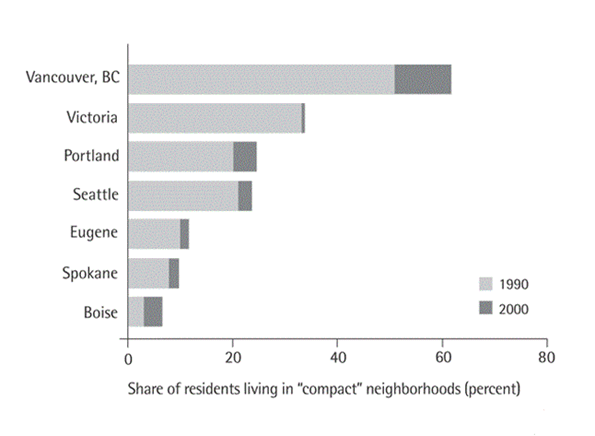

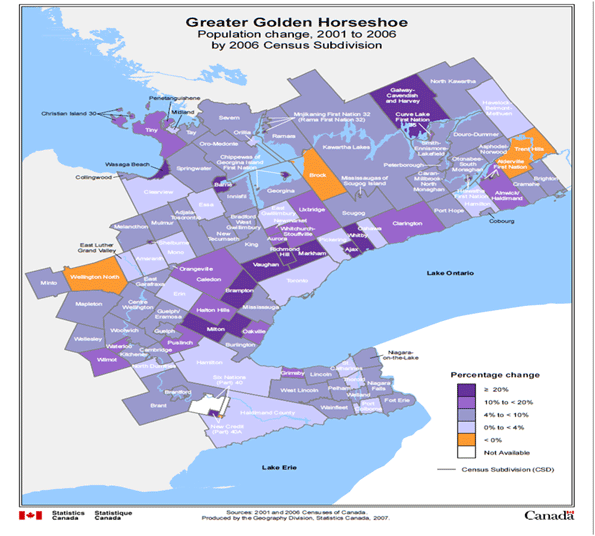

Indeed, for all the temptation by urbanists to point to Toronto’s suburban ring as an example of the decline of suburbia, the peripheral suburban areas outside of city limits have been booming. Here is a map of growth in the GTA between 2001-2006. While Toronto grew modestly, suburban cities Milton, Brampton, Vaughan, Richmond Hill, Markham, Ajax, and Whitby all grew by at least 20%. Even Oshawa, which was hit hard by the decline of the auto sector, has managed to survive, and indeed maintained a higher median income than Toronto during this period. Regional rival Mississauga eclipsed Toronto’s growth rate, and emerging regional player Barrie grew by over 20%.

In short, despite its strong financial core, Toronto is losing its standing as the go-to destination in the GTA. And it could get worse. Mississauga is working hard to lure financial services and advanced manufacturing jobs from Toronto. Several other cities, such as Guelph and Waterloo are actually competing for the very creative types that Toronto’s policies are tailored to attract. Other cities, such as Barrie are working hard to cannibalize what is left of Toronto’s manufacturing and distribution sectors. Were it not for amalgamation, Etobicoke or Scarborough could just as easily have undertaken a similar strategy to attract blue collar jobs.

The Three Cities report identifies serious regional disparities in Toronto. Unfortunately, it doesn’t provide much insight into how to fix the problem. Expanding transit options will only go so far towards this. Building more light rail may raise median incomes by attracting wealthier people to these neighbourhoods. Ironically, this will only widen the income gap. The real challenge is finding out how to create opportunities for blue collar jobs in suburban Toronto. Unfortunately, amalgamation has imposed one size fits all policies that may work downtown, but utterly fail in the suburbs and continue to drive people to the periphery outside the city limits. Ironically, the very policies that seek to halt “sprawl” may well end up exacerbating it.

Toronto Skyline photo by Smaku

Steve Lafleur is a public policy analyst and political consultant based out of Calgary, Alberta. For more detail, see his blog.