The proponents of currently fashionable planning doctrines favouring density promulgate a variety of baseless assertions to support their beliefs. These doctrines, which they group under the label of “Smart Growth”, claim, among other things, that from a health and sustainability perspective, the need to increase population densities is imperative.

With regard to health these high-density advocates have seized upon the obesity epidemic as a reason to advocate squeezing the population into high-density. This is based on a supposition that living in higher densities promotes greater physical activity and thus lower levels of obesity. They quote studies that show associations between suburban living and higher weight with its adverse health implications. But the weight differences found are minor – in the region of 1 to 3 pounds. Nor do the studies show it is suburban living that has caused this.

The suburbs, after all, have been with us for 70 years and reached its mature development over 40 years ago. Obesity, on the other hand, is a much more recent phenomenon and is primarily due to people eating too much fattening food.

Less discussed, however, are other facets to human health and it is important to consider the results of research on the association with high-density living of mental illness, children’s health, respiratory disease, heart attacks, cancer and human happiness.

A significant health issue relates to the scourge of Mental Illness. There is convincing evidence showing adverse mental health consequences from increasing density.

A monumental Swedish study of over four million Swedes examined whether a high level of urbanisation (which correlates with density) is associated with an increased risk of developing psychosis and depression. Adjustments were made to cater for individual demographic and socio-economic characteristics. It was found that the rates for psychosis (such as the major brain disorder schizophrenia) were 70% greater for the denser areas. There was also a 16% greater risk of developing depression. The paper discusses various reasons for this finding but the conclusion states: "A high level of urbanisation is associated with increased risk of psychosis and depression".

Another analysis, in the prestigious journal Nature, discusses urban neural social stress. It states that the incidence of schizophrenia is twice as high in cities. Brain area activity differences associated with urbanisation have been found. There is evidence of a dose-response relationship that probably reflects causation.

There are adverse mental (and other) health consequences resulting from an absence of green space. After allowing for demographic and socio-economic characteristics, a study of three hundred and fifty thousand people in Holland found that the prevalence of depression and anxiety was significantly greater for those living in areas with only 10% green space in their surroundings compared to those with 90% green space.

High-density advocates seem most oblivious to the needs of children. Living in high-density restricts children’s physical activity, independent mobility and active play. Many studies find that child development, mental health and physical health are affected. They also find a likely association of high-rise living with behavioural problems.

An Australian study of bringing up young children in apartments emphasizes resulting activities that are sedentary. It notes there is a lack of safe active play space outside the home – many parks and other public open spaces offer poor security. Frustrated young children falling out of apartment windows can be a tragic consequence. Children enter school with poorly developed social and motor skills. Girls living in high-rise buildings are prone to increased levels of overweight and obesity.

A British study found that 93% of children living in centrally located high-rise flats had behavioural problems and that this percentage was higher than for children living

in lower density dwellings. Anti-social behaviour often results. An Austrian study showed disturbances in classroom behaviour higher for children living in multiple-dwelling units compared to those living in lower densities.

There is also evidence of other potential health impacts on children living in higher density housing. These include short-sightedness due to restricted length of vision, and diminished auditory discrimination and reading ability due to exposure to noise.

Air pollution increases with density. This results from higher traffic densities together with less volume of air being available for dilution and dispersion. Nitrogen oxides in this pollution have adverse respiratory effects including airway inflammation in healthy people and increased respiratory symptoms in people with asthma. There is consistent evidence that proximity to busy roads, high traffic density and increased exposure to pollution are linked to a range of respiratory conditions. These can range from severe conditions (such as a higher incidence of death) to minor irritations. Moreover, these respiratory health impacts affect all age groups.

Several studies relate low birth weight to air pollution. A South Korean report, for example, found the pollutants carbon monoxide, nitrogen dioxide, sulfur dioxide, and total suspended particle concentrations in the first trimester of pregnancy pose significant risk factors for low birth weight.

Air pollution particulates are associated with killing more people than traffic accidents. Pollutants such as those emitted by vehicles are significantly associated with an increase in the risk of heart attacks and early death.

Cancer is a major health scourge and a relationship between increased colon cancer, breast cancer and total cancer mortality with population density has been found.

There is an association between overall Human Happiness and density. Professor Cummins’ Australian Unity Wellbeing Index reports that the happiest electorates have a lower population density. A United States study finds the satisfaction of older adults living in higher density social housing reduces as building height increases and as the number of units increases. By contrast, in lower densities there are higher friendship scores, greater housing satisfaction, and more active participation. This does not apply only to single family houses: Residents of garden apartments have a greater sense of community than residents of high-rise dwellings.

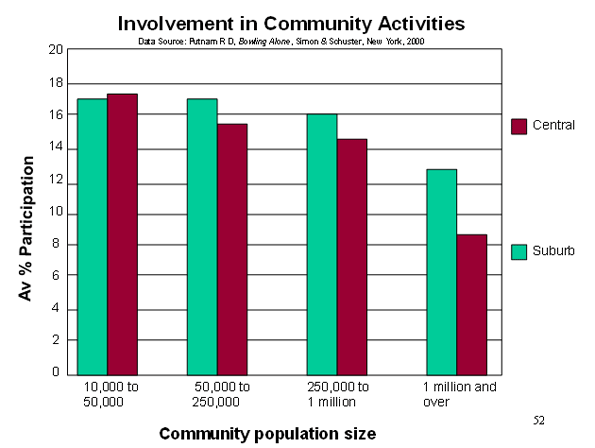

An example of misinformation on this issue can be found in R.D. Putnam’s famous book “Bowling Alone”. Putnam states that "suburbanisation, commuting and sprawl" have contributed to the decline in social engagement and social capital. However I have shown that data from charts in his book indicate quite the opposite:

Adapted from Figure 50, Putnam R D, Bowling Alone, Simon & Schuster, New York, 2000

This shows that involvement in these social activities are more common in the suburbs than in the denser centres of cities (and that they become more common as the community size and density decreases).

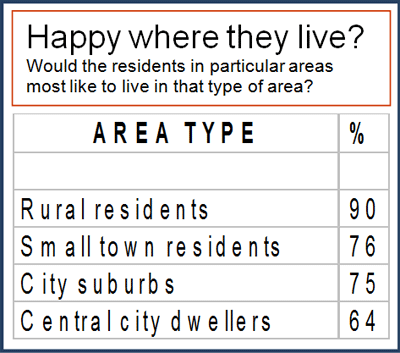

Community contentment relating to the density of surroundings is revealed by a study in New Zealand that asked people if the type of area they would most prefer to live in is similar to the area they currently live in. The responses are shown in this table.

So 90% of rural residents would prefer an area similar to their current area but only 64% of central city dwellers would prefer an area similar to their current surroundings. It can be seen that satisfaction decreases as density increases.

Thus evidence from a variety of sources points to greater human happiness and better health in lower densities — the exact opposite of the theories of the advocates for “cramming” people into ever small places.

(Dr) Tony Recsei has a background in chemistry and is an environmental consultant. Since retiring he has taken an interest in community affairs and is president of the Save Our Suburbs community group which opposes over-development forced onto communities by the New South Wales State Government.

Sydney suburb photo by BigStockPhoto.com.