Washington’s Metro (subway), often called "America’s subway," may well be America’s embarrassment. As a feature article by Robert McCartney and Paul Duggan in the Washington Post put it: “’America’s subway,’ which opened in 1976 to great acclaim — promoted as a marvel of modern transit technology and design — has been reduced to an embarrassment, scorned and ridiculed from station platforms to the halls of Congress. Balky and unreliable on its best days, and hazardous, even deadly, on its worst, Metrorail is in crisis, losing riders and revenue and exhausting public confidence." (emphasis by author.)

The Post article started out by saying: "Metro’s failure-prone subway — once considered a transportation jewel — is mired in disrepair because the transit agency neglected to heed warnings that its aging equipment and poor safety culture would someday lead to chronic breakdowns and calamities." Moreover, according to the Post, there had been plenty of warnings over the nearly half-century the trains have been operated that maintenance and safety were not receiving sufficient attention. The article notes that the transit agency has lacked a robust safety culture and "it is maintenance regime was close to negligent."

Indeed, things have gotten so bad that the new general manager Paul J. Wiedefeld ordered a one day system shutdown to make emergency repairs out of fear that a fault that killed one passenger a year ago might have recurred. The problem was considered so serious by Mr. Weidefeld that little more than 12 hours notice was provided: "Scores of passengers were sickened, one fatally, in a smoke-filled tunnel; a fire in a Metro power plant slowed and canceled trains for weeks; major stretches of the system were paralyzed for hours by a derailment stemming from a track defect that should have been fixed long before; and, on March 16, in an unprecedented workday aggravation for every Metro straphanger, the entire subway was shut down for 24 hours for urgent safety repairs."

Things are so bad that Metro officials have warned it may be necessary to shut entire subway lines for up to six months to perform necessary maintenance.

The feature length article, at nearly 5000 words, could well add to the Washington Post’s impressive list of Pulitzer Prizes.

If there were an anti-Pulitzer Prize, it might well go to James Surowiecki of The New Yorker, who opined: "Today, the Metro is in such a state that fixing it may require shutting whole lines for months at a time. It’s yet again an example for the nation, but now it’s an example of how underinvestment and political dysfunction have left America with infrastructure that’s failing and often downright dangerous."

It is hard to imagine a more inappropriate characterization. Metro’s problem has nothing to do with any national infrastructure crisis. It is a crisis of competence — the failure of its governance system to competently manage the system.

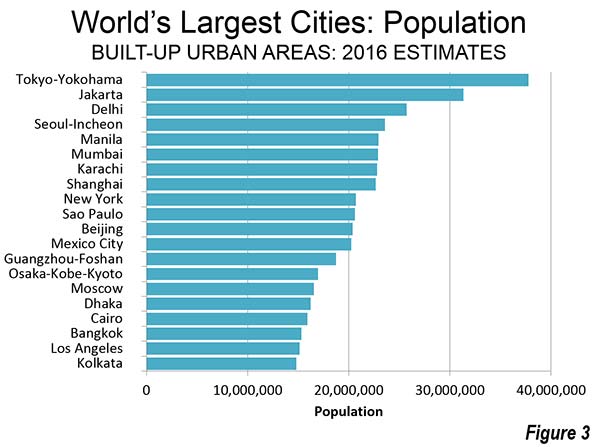

When is the last time that the entire New York subway was closed with 12 hours notice to make repairs critical to the safety of the system? Or when was the last such shutdown of the London Underground, the Paris Metro, or for that matter the Kolkata Metro or the Caracas Metro, much less the threat of closing lines for months at a time?

How many of America’s many light rail systems have shut down as a result of their having failed to sufficiently maintain their safety? There is plenty to criticize about the many new urban rail systems in the United States. They may not carry the number of passengers projected, and often have cost far more than taxpayers were told and they may not have reduced traffic congestion. But they have managed to provide safe transportation to their riders. Only one of America’s rail systems has failed so abjectly in the most fundamental of its responsibilities: America’s subway in Washington.

My one criticism of the Washington Post story is its preoccupation with finding new sources of funding. Funding levels do not excuse this failure. No one was forcing the powers that be in the Washington area to continue to expand a subway well into the hinterlands while the core was deteriorating. It was the responsibility of the governance structure of the Washington Metropolitan Area Transportation Authority (WMATA), which owns and operates Metro to put the safety of its customers first. If the priorities had been right and the system had not been built out faster than the funding would have prudently permitted, we would not be having this discussion.

Perhaps the most important lesson to be learned from the Washington Metro failure is that we need to learn the lessons. As the Post article indicates, there are multiple reasons that have contributed to Metro’s failure over decades and a number of WMATA administrations. Certainly no single board of directors or manager bears principal responsibility. It is important to learn exactly what went wrong, and examinations by organizations such as the Government Accountability Office, the Congressional Research Service, the Department of Transportation Inspector General and others would be appropriate. It is important to recognize that Metro is not the typical transit agency that has fallen into financial difficulties. This is a very special case and needs to be treated as the serious governance and management failure that it is. Answers are needed before any new money should be allowed to flow for Metro. For its part, WMATA needs to figure out what it can competently do with the money that is available.

Wendell Cox is principal of Demographia, an international pubilc policy and demographics firm. He is a Senior Fellow of the Center for Opportunity Urbanism (US), Senior Fellow for Housing Affordability and Municipal Policy for the Frontier Centre for Public Policy (Canada), and a member of the Board of Advisors of the Center for Demographics and Policy at Chapman University (California). He is co-author of the “Demographia International Housing Affordability Survey” and author of “Demographia World Urban Areas” and “War on the Dream: How Anti-Sprawl Policy Threatens the Quality of Life.” He was appointed to three terms on the Los Angeles County Transportation Commission, where he served with the leading city and county leadership as the only non-elected member. He served as a visiting professor at the Conservatoire National des Arts et Metiers, a national university in Paris.

Washington Metro photo by Ben Schumin. SchuminWeb assumed (based on copyright claims). Own work assumed (based on copyright claims).,