There is a growing body of research on the consequences of excessive land use regulation. The connection between excessive land use regulation and losses in housing affordability, has been linked to the doubling or tripling of house prices relative to incomes in places as diverse as Hong Kong, the United States, Canada, Australia, New Zealand and the United Kingdom.

More recently, research has identified serious consequences to national economies, beyond the fact that many households cannot afford to live, much less buy a home in the metropolitan areas with excessive land use regulation. Because residents such area have less income to spend due to the higher house costs, job creation and economic growth are hobbled. Rising inequality is also being cited as a consequence of excessive land use regulation.

The White House Economic Chairman’s Address

The issue has caught the attention of the White House (See: “Why White House Economists Worry about Land Use Regulations”). The Chairman of the White House Council of Economic Advisers, Jason Furman delivered an address on the subject to a conference hosted by the Urban Institute and Core Logic in Washington on November 20 (See: Barriers to Shared Growth: The Case of Land Use Regulation and Economic Rents).

Furman starts with the fundamentals: “Basic economic theory predicts—and many empirical studies confirm—that housing markets in which supply cannot keep up with demand will see housing prices rise.”

Furman cites research by Christopher Mayer of the University of Pennsylvania and C. Tsuriel Somerville of the University of British Columbia who “conclude that land use regulation and levels of new housing construction are inversely correlated, with the ability of housing supply to expand to meet greater demand being much lower in the most heavily regulated metro areas.” (see Note 1.)

The Association with Deteriorating Housing Affordability

Furman told the conference that: “While land use regulations sometimes serve reasonable and legitimate purposes, they can also give extranormal returns to entrenched interests at the expense of everyone else.” He suggested that: “There can be compelling environmental reasons in some localities to limit high-density or multi-use development. Similarly, health and safety concerns—such as an area’s air traffic patterns, viability of its water supply, or its geologic stability—may merit height and lot size restrictions.”

But, according to Furman, excessive land use regulation can severely impact the housing market:

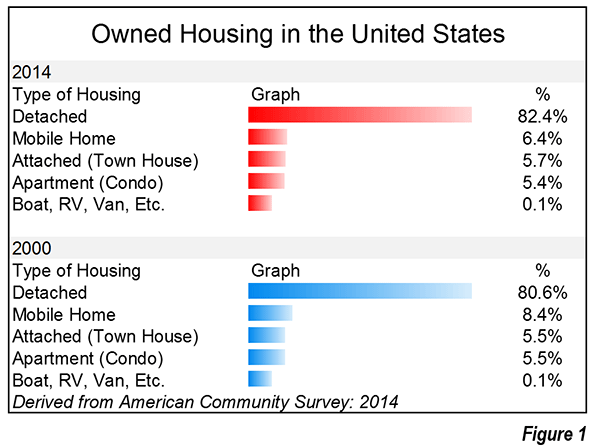

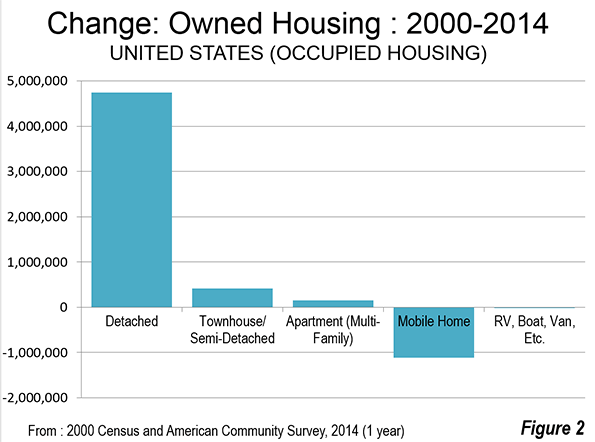

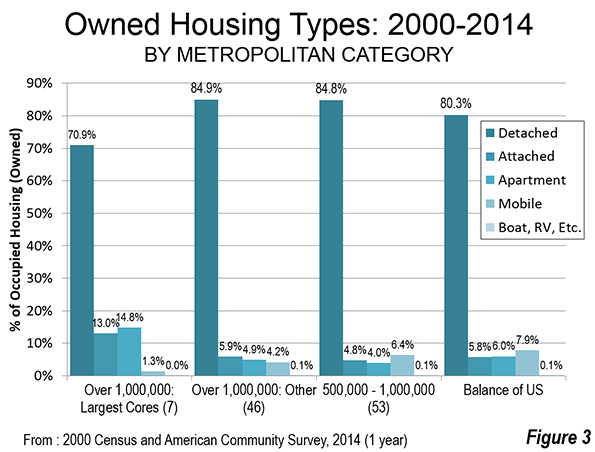

"…zoning regulations and other local barriers to housing development allow a small number of individuals to capture the economic benefits of living in a community, thus limiting diversity and mobility. The artificial upward pressure that zoning places on house prices—primarily by functioning as a supply constraint—also may undermine the market forces that would otherwise determine how much housing to build, where to build, and what type to build, leading to a mismatch between the types of housing that households want, what they can afford, and what is available to buy or rent."

In effect, excessive land use restrictions feed upon themselves to exacerbate the losses in housing affordability (Note 2):

"… some individuals are priced out of the market entirely, and homes in highly zoned areas also become even more attractive to wealthy buyers. Thus, in addition to constraining supply, zoning shifts demand outward, exerting further upward pressure on prices…"

Broader Consequences: Rising Inequality and Labor Mobility Stagnation

But the impacts go well beyond housing affordability losses. Furman expresses concern that the housing affordability losses in some cities make it difficult for households to move from elsewhere to take advantage of higher paying positions. He notes the impact of artificial constraints on housing supply as hindering mobility and suggesting that:

"Zoning and other land use regulations, by restricting the supply of housing and so increasing its cost, may make it difficult for individuals to move to areas with better-paying jobs and higher-quality schools. Barriers to geographic mobility reduce the productive use of our resources and entrench economic inequality."

He elaborated on this point:

"Reduced labor mobility may be a contributing factor to both increased inequality and lower productivity growth in the United States. This reduction in mobility has manifested itself in a wide variety of ways, including the fact that individuals are less likely to change jobs, to switch occupations or industries, or to move within States or across State lines. Businesses are creating and destroying jobs at a lower rate and fewer new businesses are being formed, both of which could be causes or consequences of a decline in labor mobility."

Part of the key to improving economic growth is greater job mobility.

"…increasing mobility ‘is going to be an important part of the solution of increasing incomes and increasing incomes across generations,’"

The greater restrictions imposed on mobility by excessive land use regulation particularly injures middle income and lower income households.

"But when zoning restricts the supply of housing and renders housing more expensive—even relative to the higher wages in the high productivity cities—then workers are less able to move, particularly those who are low income to begin with and who would benefit most from moving. As a result, existing income inequality across cities remains entrenched and may even be exacerbated, while productivity does not grow as fast it normally would."

Economic Growth and Distributional Consequences of Excessive Regulation

Mr. Furman cited ground-breaking research on the economic and distributional effects of excessive land use regulation. This includes:

Research by Raven Saks of the Federal Reserve Board, which “shows that an increase in labor demand in high regulation cities leads to a smaller increase in the housing stock, greater house price appreciation, and lower employment growth than in low regulation cities.”

Research by Peter Ganong and Daniel Shoag of Harvard University finding that the historic convergence of incomes between higher and lower income areas of the US has declined substantially. Furman said “One story for this lack of any convergence is that only high-income workers can afford to relocate to the high-productivity cities that have tight land use regulations, which reinforces existing inequality.”

Research by Chang-Tai Hseih of the University of Illinois, Chicago and Enrico Moretti of the University of California, Berkeley estimating a nearly 10 percent loss in national output from the reduced job mobility (Furman characterizes this modeled estimate as “tentative.”) Furman reported that the researchers attributed most of this loss to restrictions on housing supply.

Furman also expresses concern about intergenerational equity losses and the fact that over the past four decades land use regulations, along with larger income gains for the more affluent: “have worked toward pricing middle- and lower-income families out of the communities with the best schools.” In fact, in the major metropolitan areas, excessive land use regulations started four decades ago in California and Oregon, but with effects generally similar to what Furman suggests.

Toward Relief for Future Generations

The answer, according to Furman is better policies:

"Thus, within the broader context of declining migration rates, divergence across labor markets, and worsening housing affordability, pursuing more prudent zoning policies could also reduce inequality that is entrenched across generations."

Furman also notes the importance of studying restrictions, such as excessive land regulation because such an effort can: “…make the economy more competitive by artificial barriers, thus improving both the distribution of income and the productive capacity of the economy.”

Such improvements are genuine concerns. A year ago, the G-20 group of nations, meeting in Brisbane, adopted a communiqué declaring “better living standards” as their highest priority. They also committed to eradicating poverty. However, since last year, economic growth has been disappointing, as the post-Great Recession recovery appears stalled in second gear, at best. Yet despite the weak economy, housing affordability has deteriorated even more sharply in G-20 member states Australia, Canada, China and the United Kingdom.

As the US research indicates, real household income growth can be severely hobbled if much or all of the modestly rising incomes is consumed by extraordinarily rising housing costs. This also does nothing to reduce, much less eradicate poverty. Governments from Sacramento and Olympia to Sydney and London should strive to improve the situation by reforming counterproductive and economically destructive land use regulations.

Note 1: The academic references in this article are detailed in longer discussions in our new reports, A Question of Values: Middle-Income Housing Affordability and Urban Containment Policy, and Putting People First: An Alternative Perspective with an Evaluation of the NCE Cities “Trillion Dollar” Report.

Note 2: In a footnote to the speech transcript, Furman notes that housing housing affordability requires comparison to incomes rather than simple house price comparisons: “Yet, affordability measures are relative to wages in an area not levels of house prices across cities.” This required nexus to income is not always evident in research on housing affordability.

Wendell Cox is Chair, Housing Affordability and Municipal Policy for the Frontier Centre for Public Policy (Canada), is a Senior Fellow of the Center for Opportunity Urbanism (US), a member of the Board of Advisors of the Center for Demographics and Policy at Chapman University (California) and principal of Demographia, an international public policy and demographics firm.He is co-author of the "Demographia International Housing Affordability Survey" and author of "Demographia World Urban Areas" and "War on the Dream: How Anti-Sprawl Policy Threatens the Quality of Life." He was appointed to three terms on the Los Angeles County Transportation Commission, where he served with the leading city and county leadership as the only non-elected member. He served as a visiting professor at the Conservatoire National des Arts et Metiers, a national university in Paris.

Photo: Entering Oregon sign