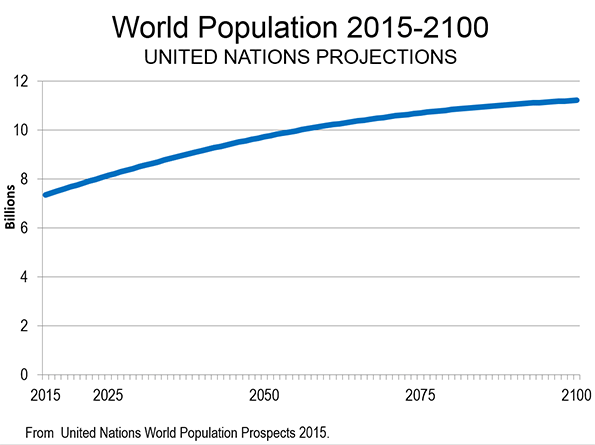

According to the new United Nations World Population Prospects: The 2015 Revision, the population of the world is projected to rise from 7.3 billion in 2015 to 11.2 billion in 2100. This represents a 53 percent increase. However, over the period, population growth will moderate substantially. This is indicated by the annual growth rate the first year (2015 to 2016), at 1.1 percent, compared to the last year (2099 to 2100) at 0.1 percent. Annual population growth is projected to decline 90 percent from the beginning of the period to the end (Figure 1).

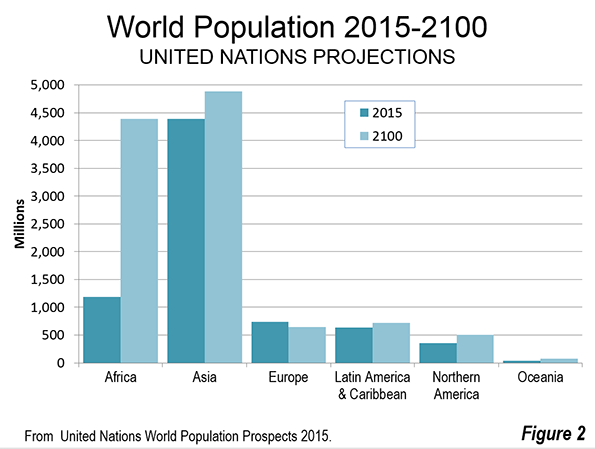

Growth by Continent

The distribution of growth among the continents will be anything but even. Approximately 83 percent of the growth is projected to be in Africa, which is to grow approximately 270 percent. Asia is expected to account for 13 percent of the world’s growth and add 11 percent to its population. Northern America (Note), while growing 40 percent is expected to account for four percent of the world’s population growth. Latin America and the Caribbean are expected to account for 2.2 percent of the world’s growth, and add 14 percent to their population. Europe (including all of Russia) is expected to decline in population by 13 percent (Figure 2).

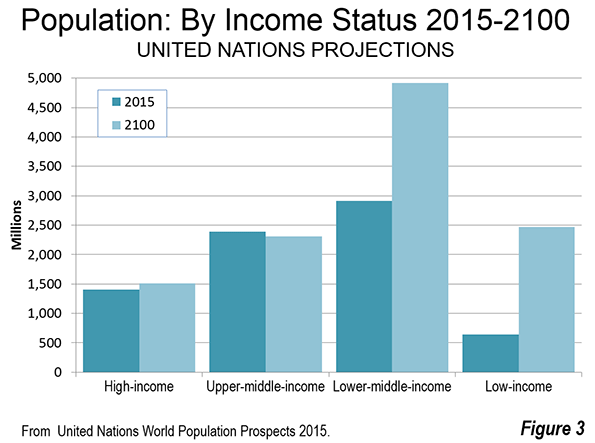

Population Growth by Income Status

World population growth is expected to vary widely by current income status (Figure 3). Income status is indicated on page 137 of this United Nations publication.

The world’s high income nations are expected to add only eight percent (111 million) to their population and will represent only three percent of the population growth. These nations are principally in North America and Europe, but also include Japan, South Korea, Saudi Arabia and others.

The world’s upper middle income nations are expected to experience a population decline of three percent, which amounts to a loss of 82 million residents. China, Russia, Mexico, South Africa, Iran and Brazil are examples of upper-middle income nations. When combined with the high income gain noted above the more affluent half of the world’s nations would add 29 million residents, or just 0.7 percent of the world’s growth. This is fewer people than live in the Tokyo metropolitan area.

This means that more than 99 percent of world growth from 2015 to 2100 is expected to be among the lower income nations. The lower middle income nations would gain 2 billion people, representing 52 percent of the population growth. The lower-middle income nations include India, Indonesia, Nigeria, the Philippines, Vietnam, Guatemala and others.

The lower income nations would gain 1.8 billion people, capturing 47 percent of the world’s growth. The lower income nations include Bangladesh, Tanzania, Myanmar, the Democratic Republic of the Congo and others.

In the high income and upper middle income regions, population growth will be also anything but consistent. Nations such as the United States, the United Kingdom, France, Canada and Australia are expected to grow far faster. The United States is expected to add 40 percent to its population and more than four times the population growth of all of the upper half of nations. Canada (up 39 percent) and Australia (up 77 percent), combined, are expected to add more population than the total upper income half of nations. These gains will be largely offset by losses in Japan, Germany, South Korea, Italy and others.

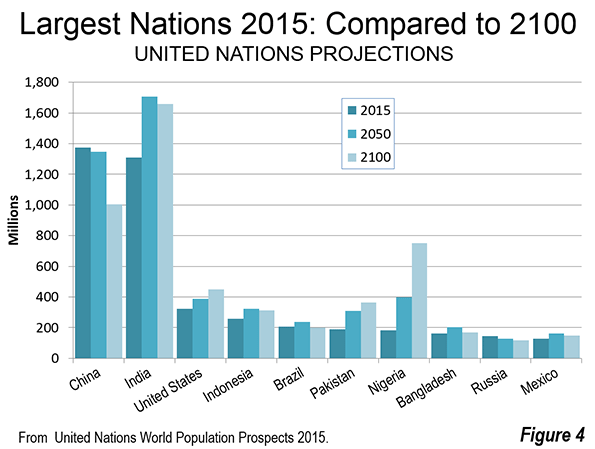

Largest Population by Nation

China, with the largest population in 2015, is expected to fall behind India in 2050 and remain in second place by 2100. India is expected to be the largest nation in both 2050 and 2100. However, India’s population will be less in 2100 than it was in 2050.

Eight of the 10 most populated nations, including India and China are expected to have a lower population in 2100 than in 2050 (Figure 4). Pakistan is expected to reach its population peak in 2095 and start declining in 2096. This leaves only the United States among today’s today’s 10 largest nations that is expected to be adding population in 2100. The growth rate between 2099 and 2100 (0.2 percent) is expected to be considerably below the growth rate at the beginning of the period (2015-2016), which was 0.7 percent.

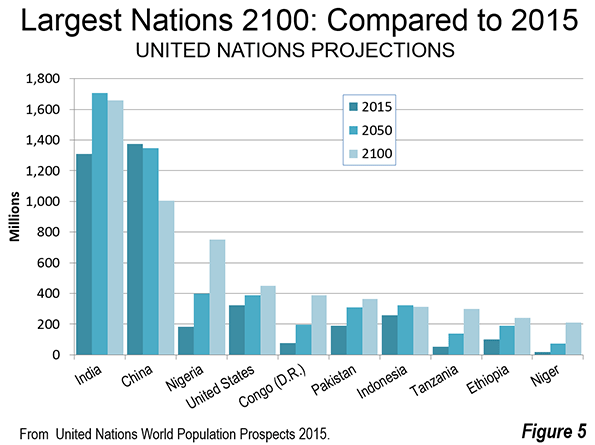

By 2100, there are expected to be substantial changes to the top 10 nations in population. Five of the 10 largest nations in the world are expected to be in Africa. This is an increase from one in 2015 (Figure 5). Nigeria will have replaced the United States as the third largest nation, with approximately 750 million people, having more than quadrupled in size. The Democratic Republic of the Congo (Congo – Kinshasa) would rank fifth, and is expected to reach 390 million people, quintupling in size. Tanzania would rank eighth, reaching 300 million residents, nearly 6 times its 2015 population. Ethiopia would have more than 240 million residents, 2.5 times its current population and would rank ninth. The 10th largest nation would be Niger, with 210 million residents, a figure 10 times its 2015 level. Among the African nations in the top 10, only Ethiopia would be declining by 2100, having reached its population peak in 2097.

Pakistan would retain its current sixth position, while Indonesia would fall from 4th to 7th. As noted above, India would be the largest nation in China would be second largest in 2100. By that date India would have an overall gain of approximately 350 million people from 2015, while China would lose 370 million people. The United States would add more than 125 million people. Brazil, which is currently ranked 5th, would lose approximately 10 million people and fall to 13th position. Eighth ranked Bangladesh, which was long among the fastest growing nations in the world, would gain only 10 million people and fall to 14th position. Russia, ranked 9th, would fall to 23rd, losing 25 million residents. Mexico, ranked 10th, would gain 20 million residents, and would be ranked 18th in 2100.

The Uncertainty of Projections

Of course projections of any kind are subject to wide error ranges. Economic growth, the extent of poverty, wars, social trends, medical advances and other factors can interfere. The simple fact is that none of us and no organization knows the future for sure. One study of UN population trends in six Southeast Asian nations found that 1980 projections from 1950 were 13.9 percent off by nation, with a range from minus 20 percent to plus 27 percent. There had been some improvement in comparing 1975 projections to 2000 actual populations, with an average error of 8.2 percent. The range was little improved, from minus 23 percent to plus 25 percent. Obviously projections are likely to be much more accurate in early years and the chances for greater accuracy are improved in larger nations or regions.

A World of Challenges

Regardless of the extent of accuracy, which cannot be known at this point, the projections indicate a continuation of trends that cause concern. A world that is experiencing virtually 100 percent of its growth in its poorest areas cannot help but face a tougher future. This makes it clear that the principal priority of governments around the world should be to improve affluence and reduce poverty. The challenges are gargantuan, but focusing on these issues is likely to result in a better, though less than ideal, world.

Note: Northern America includes Canada, the United States, Greenland, Bermuda and the French territory of Saint Pierre and Miquelon.

Photograph: Western Railway Headquarters (Churchgate), Mumbai, India (by author)

Wendell Cox is Chair, Housing Affordability and Municipal Policy for the Frontier Centre for Public Policy (Canada), is a Senior Fellow of the Center for Opportunity Urbanism (US), a member of the Board of Advisors of the Center for Demographics and Policy at Chapman University (California) and principal of Demographia, an international public policy and demographics firm.

He is co-author of the "Demographia International Housing Affordability Survey" and author of "Demographia World Urban Areas" and "War on the Dream: How Anti-Sprawl Policy Threatens the Quality of Life." He was appointed to three terms on the Los Angeles County Transportation Commission, where he served with the leading city and county leadership as the only non-elected member. He served as a visiting professor at the Conservatoire National des Arts et Metiers, a national university in Paris.