Core Based Statistical Area (CBSA) is the Office of Management and Budget’s (OMB) way of defining metropolitan regions. The OMB (not the Census Bureau) defines criteria for delineating its three metropolitan concepts, combined statistical areas, metropolitan statistical areas, and micropolitan statistical areas. The CBSA has obtained little use since this adoption for the 2000 census. According to OMB:

"A CBSA is a geographic entity associated with at least one core of 10,000 or more population, plus adjacent territory that has a high degree of social and economic integration with the core as measured by commuting ties."

In this context, core means urban area. If an urban area has 50,000 or more population, OMB defines a metropolitan area around it. If an urban area has 10,000 or more population but fewer than 50,000 residents, OMB defines a micropolitan area around it.

It is also important to understand that CBSAs, whether CSAs, metropolitan areas, or micropolitan areas are not urban areas. In fact, 94% of the area in CBSAs is rural — only 6% is urban (built-up urban cores and suburbs).

Combined statistical areas (CSAs) are made up of adjacent CBSAs that have a significant amount of commuting between them, but less than required for a metropolitan area or a micropolitan area. In some cases the CSAs seem so obvious as to make the smaller metropolitan area definitions seem ludicrous. One keen observer, Michael Barone of the Washington Examiner, put San Francisco and San Jose, as well as Los Angeles and Riverside-San Bernardino together in his recent analysis of population growth, because, as he rightly pointed out, they seem to "flow together."

Some CSAs are very large. For example the New York CSA is composed of 8 metropolitan areas (New York (NY-NJ-PA), Bridgeport (CT), New Haven (CT), Trenton (NJ), Allentown (PA-NJ), Kingston (NY). Torrington (CT) and East Stroudsburg (PA). On the other hand, many major metropolitan areas are not a part of a CSA, such as Phoenix and San Diego.

Since the term CBSA seems unlikely to achieve popular usage, this article uses the term "commuter shed" to denote the highest local level of metropolitan definition. The highest level for the largest regions are is the combined statistical area (CSA). In others they are defined as a metropolitan area or micropolitan area. The result is a consistent standard of economic geography defined by commuting. Yet such lists are rare or non-existent. A table of all 569 commuter sheds (over 1,000,000 population) is posted to demographia.com.

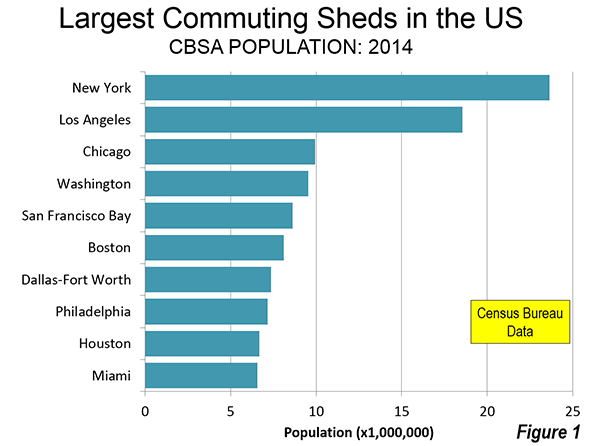

10 Largest Commuter Sheds

As a 2014, there were 60 commuter sheds in the United States with more than 1 million population (Table).

Not surprisingly, the nation’s largest commuter shed is New York. New York stretches from New Haven and Bridgeport, and Connecticut which are separate metropolitan areas out to Allentown which is principally in Pennsylvania and Trenton in New Jersey. The New York commuter shed has a population of 23.6 million. In fact, given the extensive suburban rail transit service between Southwestern Connecticut and New York City, it may be surprising that New Haven and Bridgeport are separate metropolitan areas, both with nearly 1,000,000 population. Moreover, there is virtually no break in the continuously built-up area between New York and southwestern Connecticut (Fairfield and New Haven counties) — they "flow together" to use Barone’s term. Since 2010, the Allentown metropolitan area, with nearly 1,000,000 population, was added to the New York CSA.

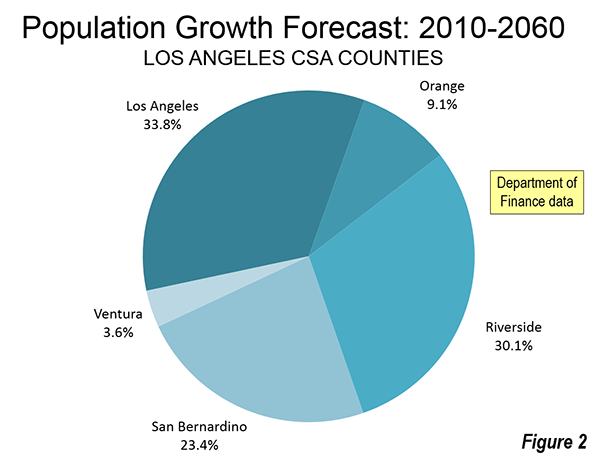

The second largest commuter shed is Los Angeles-Inland Empire, with 18.6 million residents. This includes the Los Angeles metropolitan area (Los Angeles and Orange Counties, Ventura County and the Riverside San Bernardino metropolitan area (Inland Empire, including Riverside and San Bernardino County), which is one of the largest in the nation, with more than 4 million population. Here, as in New York, there is virtually no break in the built-up urbanization between the two urban areas, Los Angeles and Riverside-San Bernardino.

Chicago is the third largest commuter shed, though its adjacent metropolitan areas are far smaller than in New York and Los Angeles. Chicago is also growing very slowly, with its population increase over the last year so small that it will take nearly to 2020 to reach 10 million, even though it only has 72,000 to go.

Just below Chicago, Washington and Baltimore combine to form nation’s fourth largest commuter shed. Already with more than 9.5 million residents and strong growth this decade, Washington-Baltimore could pass 10 million population and Chicago by 2020. Washington-Baltimore is unique in combining two of the nation’s historically largest and most intensely developed core municipalities along with the much more extensive suburbs (which contain 85% of the population). Washington-Baltimore now extends to Franklin County, Pennsylvania.

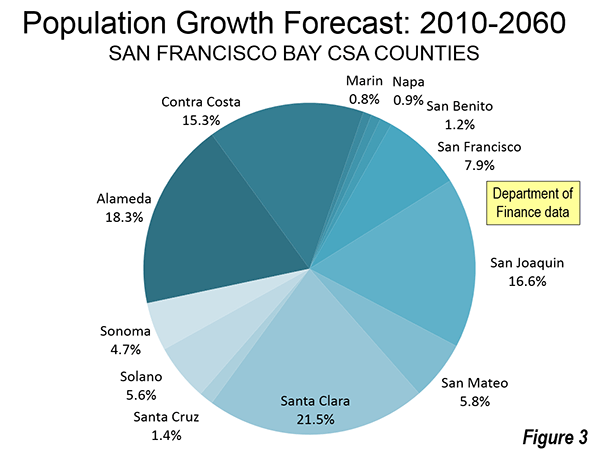

The fifth largest metropolitan complex is the San Francisco Bay Area with a population of 8.6 million. This includes the San Francisco, San Jose, Vallejo, Santa Rosa, Santa Cruz metropolitan areas and the recently added Stockton metropolitan area.. There is no break in the urbanization between San Francisco and San Jose.

The Boston CBSA was enlarged during the last decade to include Providence, a major metropolitan area in its own right. Boston also includes the Worcester metropolitan area, which is nearing 1,000,000 population. Boston-Providence has a population of 8.1 million.

The top 10 is rounded out by Dallas-Fort Worth (7.4 million), Philadelphia (7.2 million), Houston (6.7 million), and Miami (6.6 million).

The largest metropolitan complex in the nation that is not a part of a CSA is Phoenix, which is ranked 14th. Only one other commuter sheds in the top 20 is not a CSA (San Diego) and only six of the 60 commuter sheds with more than 1,000,000 population is not a CSA.

Fastest Growing Commuter Sheds

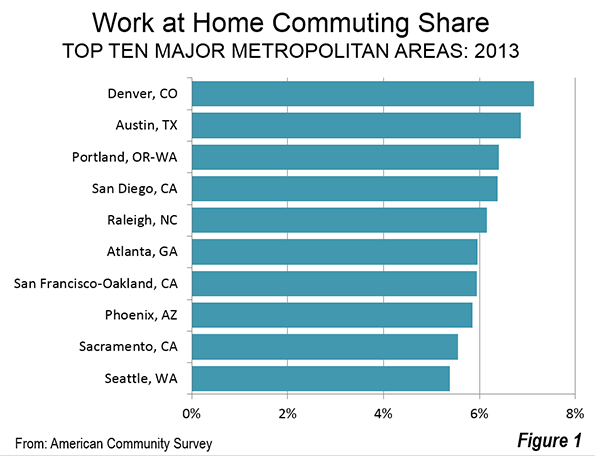

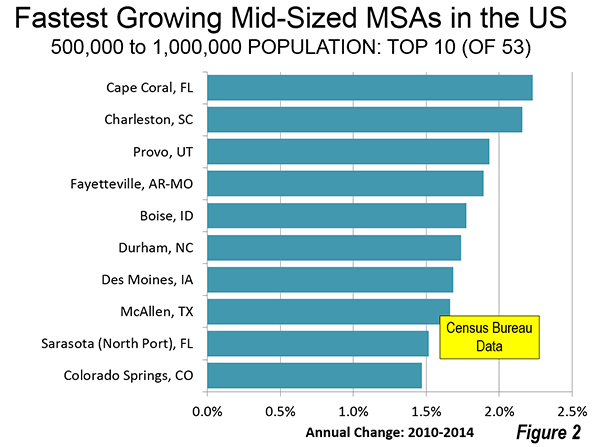

The fastest commuter shed growth rates are in the South, which accounts for eight of the ten fastest growing commuter shed’s. Austin ranks number one in annual percentage growth between 2010 and 2014, a position it also holds among major metropolitan areas. Cape Coral (Florida) ranks second. Cape Coral also ranks as the fastest growing among the midsized metropolitan areas (from 500,000 to 1,000,000 population). Houston ranks third in growth rate. Houston and Dallas-Fort Worth are the only commuter sheds with more than 5 million population that are among the top 10 in growth. The two non-Southern top 10 entries are from the West: Denver and Phoenix (Figure 2).

Slowest Growing Commuter Sheds

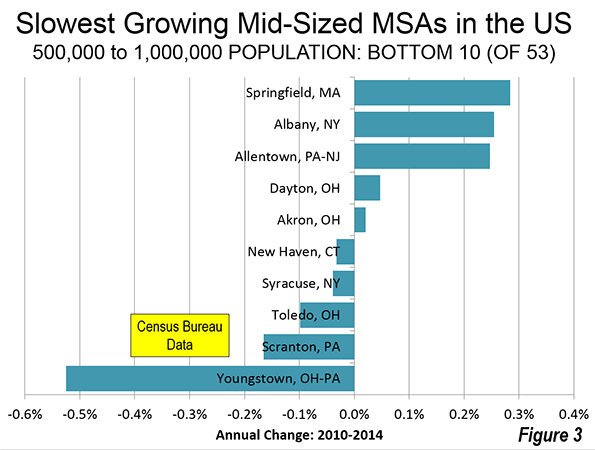

All of the 10 slowest growing major commuter sheds are in the old industrial heartland of the Northeast and Midwest. Cleveland-Akron is the slowest growing, having lost approximately 0.1 percent of its population annually. Pittsburgh, Dayton, Buffalo and Detroit have also lost population.

Continuing Dispersion

The dispersion of US metropolitan areas continues, with perhaps the ultimate example of Portland (Oregon), which was recently combined with four other metropolitan areas (see: Driving Farther to Quality in Portland). The "flowing together" suggest that the combined statistical area may be an increasingly important in assessing regional trends.

| Core Based Statistical Areas (Commuter Sheds): United States | |||||

| Over 1,000,000 Population in 2014 | |||||

| 2014 Population Rank | Metropolitan Area | 2010 | 2014 | Annual % Change: 2010-2014 | Growth Rank |

| 1 | New York-New Haven, NY-NJ-CT-PA CSA | 23.077 | 23.633 | 0.56% | 41 |

| 2 | Los Angeles-Inland Empire, CA CSA | 17.877 | 18.550 | 0.87% | 30 |

| 3 | Chicago, IL-IN-WI CSA | 9.841 | 9.928 | 0.21% | 50 |

| 4 | Washington-Baltimore, DC-MD-VA-WV-PA CSA | 9.052 | 9.547 | 1.26% | 18 |

| 5 | San Fransicsco-San Jose, CA CSA | 8.154 | 8.607 | 1.28% | 17 |

| 6 | Boston-Providence, MA-RI-NH-CT CSA | 7.894 | 8.100 | 0.61% | 38 |

| 7 | Dallas-Fort Worth, TX-OK CSA | 6.818 | 7.353 | 1.79% | 8 |

| 8 | Philadelphia, PA-NJ-DE-MD CSA | 7.068 | 7.165 | 0.32% | 47 |

| 9 | Houston, TX CSA | 6.115 | 6.686 | 2.13% | 3 |

| 10 | Miami-West Palm Beach, FL CSA | 6.168 | 6.558 | 1.46% | 14 |

| 11 | Atlanta, GA CSA | 5.910 | 6.259 | 1.36% | 16 |

| 12 | Detroit, MI CSA | 5.319 | 5.315 | -0.02% | 56 |

| 13 | Seattle, WA CSA | 4.275 | 4.527 | 1.36% | 15 |

| 14 | Phoenix, AZ MSA | 4.193 | 4.489 | 1.62% | 9 |

| 15 | Minneapolis-St. Paul, MN-WI CSA | 3.685 | 3.835 | 0.94% | 26 |

| 16 | Cleveland-Akron, OH CSA | 3.516 | 3.498 | -0.12% | 60 |

| 17 | Denver, CO CSA | 3.091 | 3.345 | 1.88% | 6 |

| 18 | San Diego, CA MSA | 3.095 | 3.263 | 1.25% | 20 |

| 19 | Portland-Salem, OR-WA CSA | 2.921 | 3.060 | 1.10% | 23 |

| 20 | Orlando-Daytona Beach, FL CSA | 2.818 | 3.046 | 1.84% | 7 |

| 21 | Tampa-St. Petersburg, FL MSA | 2.784 | 2.916 | 1.10% | 22 |

| 22 | St. Louis, MO-IL CSA | 2.893 | 2.911 | 0.15% | 52 |

| 23 | Pittsburgh, PA-OH-WV CSA | 2.661 | 2.654 | -0.06% | 59 |

| 24 | Charlotte, NC-SC CSA | 2.376 | 2.538 | 1.57% | 11 |

| 25 | Sacramento, CA CSA | 2.415 | 2.513 | 0.94% | 27 |

| 26 | Salt Lake City-Ogden, UT CSA | 2.272 | 2.424 | 1.54% | 12 |

| 27 | Kansas City, MO-KS CSA | 2.343 | 2.412 | 0.68% | 36 |

| 28 | Columbus, OH CSA | 2.309 | 2.398 | 0.90% | 28 |

| 29 | Indianapolis, IN CSA | 2.267 | 2.354 | 0.89% | 29 |

| 30 | San Antonio, TX MSA | 2.143 | 2.329 | 1.98% | 4 |

| 31 | Las Vegas, NV-AZ CSA | 2.195 | 2.315 | 1.26% | 19 |

| 32 | Cincinnati, OH-KY-IN CSA | 2.174 | 2.208 | 0.37% | 46 |

| 33 | Raleigh-Durham, NC CSA | 1.913 | 2.075 | 1.94% | 5 |

| 34 | Milwaukee, WI CSA | 2.026 | 2.044 | 0.21% | 51 |

| 35 | Austin, TX MSA | 1.716 | 1.943 | 2.97% | 1 |

| 36 | Nashville, TN CSA | 1.788 | 1.913 | 1.59% | 10 |

| 37 | Norfolk-Virginia Beach, VA-NC CSA | 1.779 | 1.819 | 0.53% | 43 |

| 38 | Greensboro-Winston-Salem, NC CSA | 1.589 | 1.630 | 0.60% | 39 |

| 39 | Jacksonville, FL-GA CSA | 1.470 | 1.543 | 1.14% | 21 |

| 40 | Louisville, KY-IN CSA | 1.460 | 1.499 | 0.62% | 37 |

| 41 | Hartford, CT CSA | 1.486 | 1.488 | 0.02% | 55 |

| 42 | New Orleans, LA-MS CSA | 1.414 | 1.480 | 1.09% | 24 |

| 43 | Grand Rapids, MI CSA | 1.379 | 1.421 | 0.71% | 34 |

| 44 | Greenville, SC CSA | 1.362 | 1.410 | 0.81% | 33 |

| 45 | Oklahoma City, OK CSA | 1.322 | 1.409 | 1.50% | 13 |

| 46 | Memphis, TN-MS-AR CSA | 1.353 | 1.370 | 0.29% | 48 |

| 47 | Birmingham, AL CSA | 1.303 | 1.317 | 0.27% | 49 |

| 48 | Richmond, VA MSA | 1.208 | 1.260 | 1.00% | 25 |

| 49 | Harrisburg, PA CSA | 1.219 | 1.240 | 0.39% | 45 |

| 50 | Buffalo, NY CSA | 1.216 | 1.215 | -0.02% | 57 |

| 51 | Rochester, NY CSA | 1.175 | 1.177 | 0.05% | 54 |

| 52 | Albany, NY CSA | 1.169 | 1.174 | 0.10% | 53 |

| 53 | Albuquerque, NM CSA | 1.146 | 1.166 | 0.40% | 44 |

| 54 | Tulsa, OK CSA | 1.106 | 1.139 | 0.69% | 35 |

| 55 | Fresno, CA CSA | 1.081 | 1.121 | 0.84% | 32 |

| 56 | Knoxville, TN CSA | 1.077 | 1.104 | 0.58% | 40 |

| 57 | Dayton, OH CSA | 1.080 | 1.078 | -0.05% | 58 |

| 58 | Tucson, AZ CSA | 1.028 | 1.051 | 0.53% | 42 |

| 59 | El Paso, TX-NM CSA | 1.013 | 1.050 | 0.85% | 31 |

| 60 | Cape Coral, FL CSA | 0.940 | 1.028 | 2.13% | 2 |

| In millions | |||||

| Data from US Census Bureau | |||||

| Metropolitan Statistical Areas shown only if not in a Combined Statistical Area. | |||||

Wendell Cox is Chair, Housing Affordability and Municipal Policy for the Frontier Centre for Public Policy (Canada), is a Senior Fellow of the Center for Opportunity Urbanism (US), a member of the Board of Advisors of the Center for Demographics and Policy at Chapman University (California) and principal of Demographia, an international public policy and demographics firm.

He is co-author of the "Demographia International Housing Affordability Survey" and author of "Demographia World Urban Areas" and "War on the Dream: How Anti-Sprawl Policy Threatens the Quality of Life." He was appointed to three terms on the Los Angeles County Transportation Commission, where he served with the leading city and county leadership as the only non-elected member. He served as a visiting professor at the Conservatoire National des Arts et Metiers, a national university in Paris.

Photo: Albany (NY) City Hall (by author)