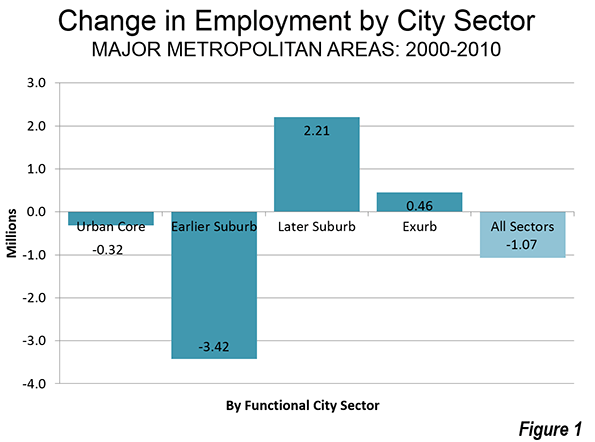

The United States lost jobs between 2000 and 2010, the first loss between census years that has been recorded in the nation’s history. The decline was attributable to two economic shocks, the contraction following the 9/11 attacks and the Great Recession, the worst financial crisis since the Great Depression. Yet, even in this moribund job market, employment continued to disperse in the nation’s major metropolitan areas.

This is the conclusion of a small area analysis (zip code tabulation areas) of data from County Business Patterns, from the Census Bureau, which captures nearly all private sector employment and between 85 and 90 percent of all employment (Note 1).

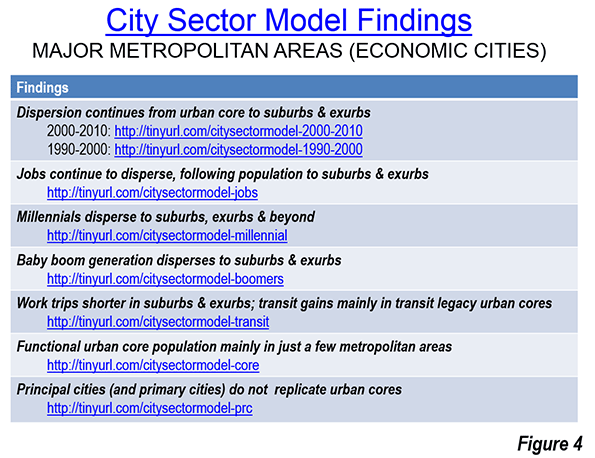

The small area analysis avoids the exaggeration of urban core data that necessarily occurs from reliance on the municipal boundaries of core cities (which are themselves nearly 60 percent suburban or exurban, ranging from as little as three percent to virtually 100 percent). This "City Sector Model" small area analysis method is described in greater detail in Note 2.

Distribution of Employment in Major Metropolitan Areas

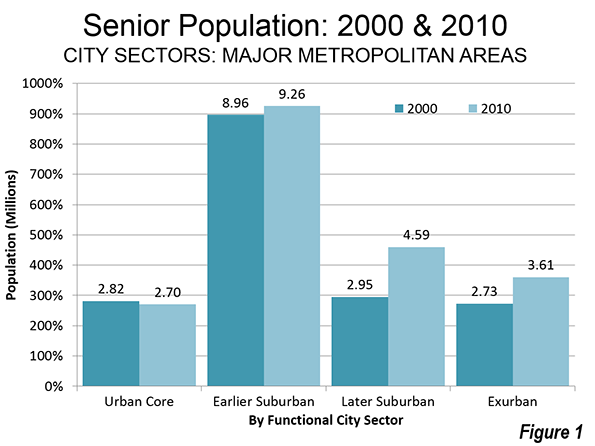

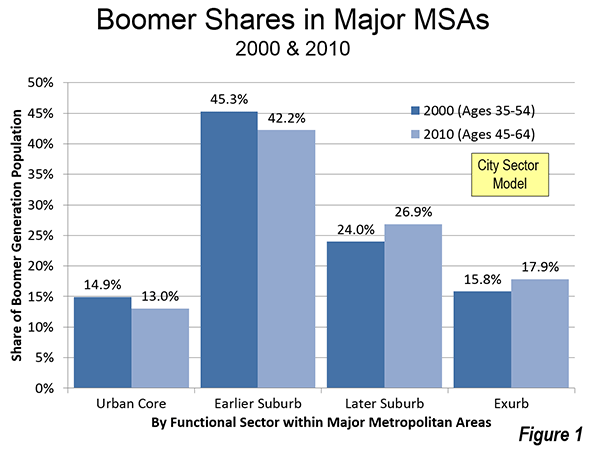

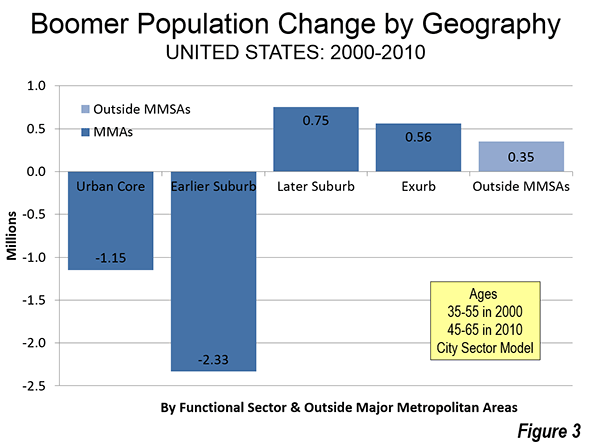

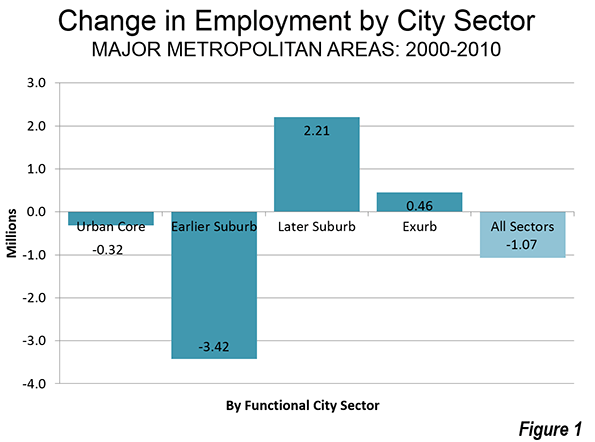

County Business Pattern data indicates that employment dropped approximately 1,070,000 in the 52 major metropolitan areas (those with more than 1,000,000 population) between 2000 and 2010. The inner city sectors (the functional urban cores and earlier suburbs) were hard-hit. Together the inner sectors, the functional urban cores and the earlier suburbs, lost 3.74 million jobs. The outer sectors, the later suburbs and the exurbs, gained 2.67 million jobs (Figure 1).

There were job losses of more than 300,000 in the functional urban cores, and even larger losses (3.2 million) in the earlier suburbs. The functional urban cores are defined by the higher population densities that predominated before 1940 and a much higher dependence on transit, walking and cycling for work trips. The earlier suburbs have median house construction dates before 1980.

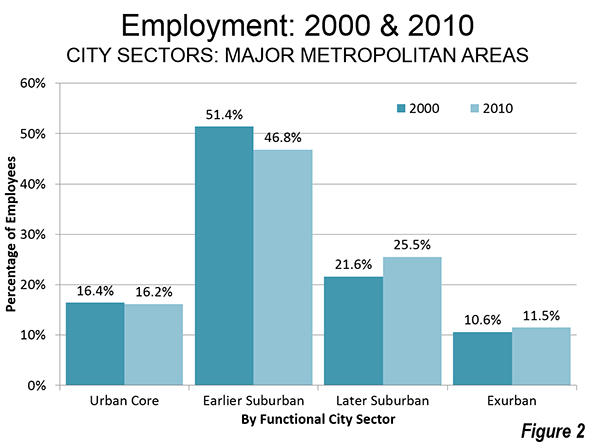

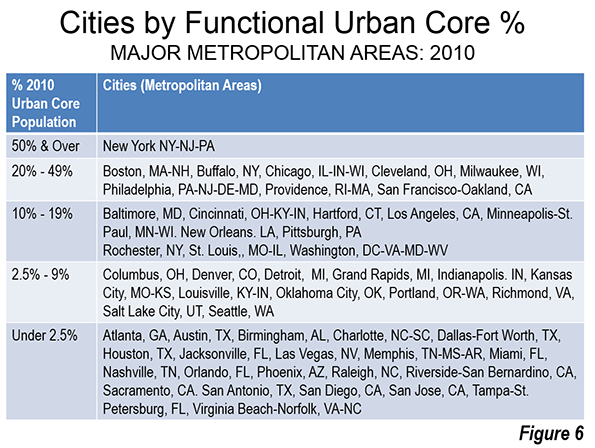

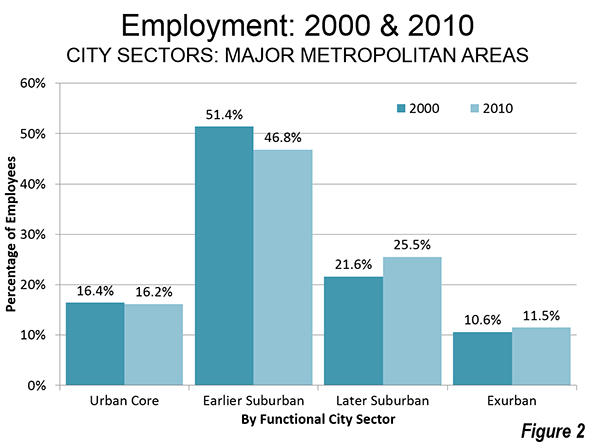

The share of major metropolitan area employment in the functional urban cores dropped from 16.4 percent in 2000 to 16.2 percent in 2010. This compares to the 8 percent of major metropolitan employment that is downtown (central business district) areas. The notion, however, that metropolitan areas are dominated by their downtowns is challenged by the fact that 84 percent of jobs are outside the functional urban cores.

The largest percentage of major metropolitan areas is clustered in the earlier suburbs, those with median house construction dates from 1946 to 1979. In 2010, 46.8 percent of the jobs were in the earlier suburbs, a decline from 51.4 percent in 2000.

These losses in employment shares in the two inner city sectors were balanced somewhat by increases in the outer sectors, the later suburbs (with median house construction dates of 1980 or later) and the exurbs, which are generally outside built-up urban areas. The increase was strongest in the later suburbs, where, where employment increased by 2.6 million. The share of employment in the later suburbs rose to 25.5 percent from 21.6 percent. There was also a 600,000 increase in exurban employment. The exurban share of employment rose to 11.5 percent from 10.6 percent (Figure 2).

The Balance of Residents and Jobs

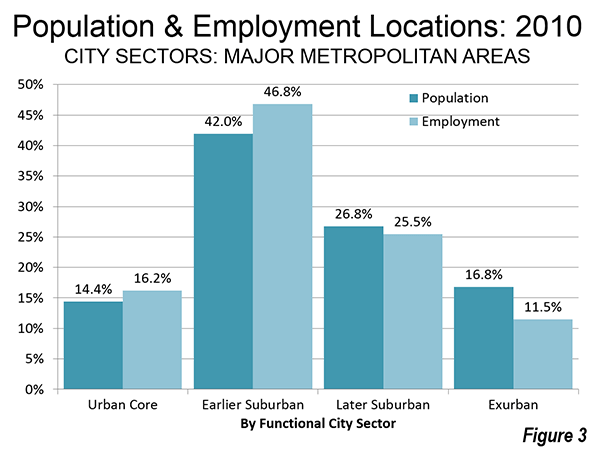

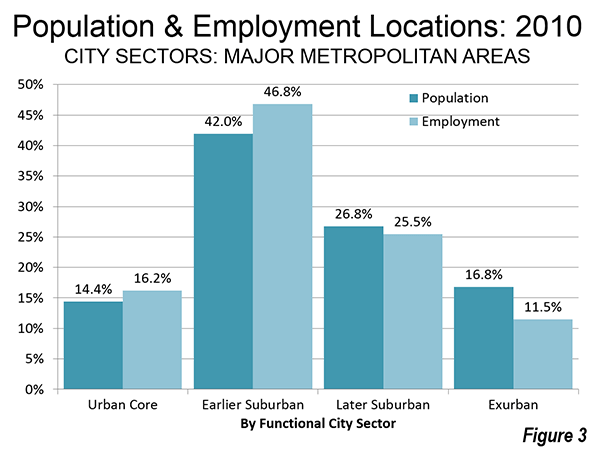

There is a surprisingly strong balance between population and employment within the city sectors, which belies the popular perception by some press outlets and even some urban experts that as people who farther away from the urban core, they have to commute farther. In fact, 92 percent of employees do not commute to downtown, and as distances increase, the share of employees traveling to work downtown falls off substantially. As an example, only three percent of working residents in suburban Hunterdon County, New Jersey (in the New York metropolitan area), work in the central business district, Manhattan, while 80 percent work in relatively nearby areas of the outer combined metropolitan area.

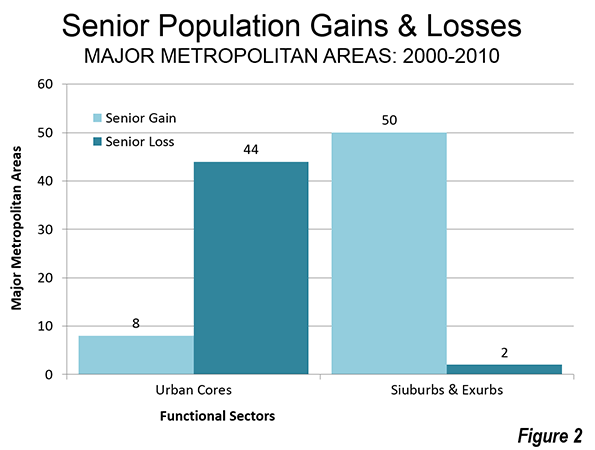

It is to be expected that the functional urban core would have a larger share of employment than population. However the difference is not great, with 16.2 percent of employment in the functional urban core and 14.4 percent of the population. The earlier suburbs have by far the largest share of the population at 42.0 percent. They also have the largest share of employment, at 46.8 percent. The later suburbs have 26.8 percent of the population, slightly more than their 25.5 percent employment share. The largest difference is, as would be expected, is in the exurbs, with 16.8 percent of major metropolitan area residents and 11.5 percent of employment (Figure 3). It is notable, however, that the difference between the share of population and employment varies less than 15 percent in the three built-up urban area sectors (urban core, earlier suburbs and later suburbs), though the difference was greater in the exurbs.

How Employment Followed Population in the 2000s

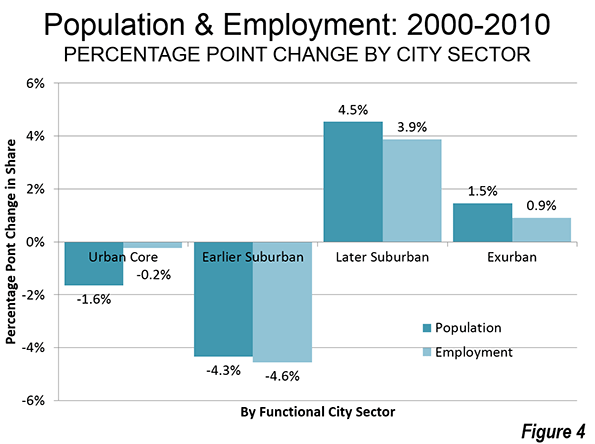

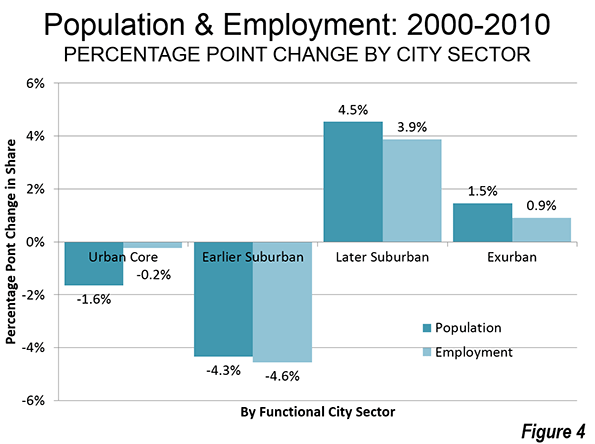

The outward shifts of population and employment are between in the city sectors. In the earlier suburbs, where the population and employment is the greatest, the population share declined 4.3 percentage points, while the employment share declined a near lockstep 4.6 percentage points. The later suburbs had a 4.5 percentage point increase in population share, followed closely a near lockstep 3.9 percentage point increase in employment share. In the exurbs, a 1.5 percentage point increase in the population share was accompanied by a 0.9 percentage point increase in the employment share. The connection is less clear in the functional urban core, where a 1.6 percentage point drop in the population share was associated with a 0.2 percentage point reduction in the employment share (Figure 4).

The similarity in population and employment shares between the city sectors is an indication that employment growth has been geographically tracking population growth for decades, as cities have evolved from moncentricity to polycentricity and beyond.

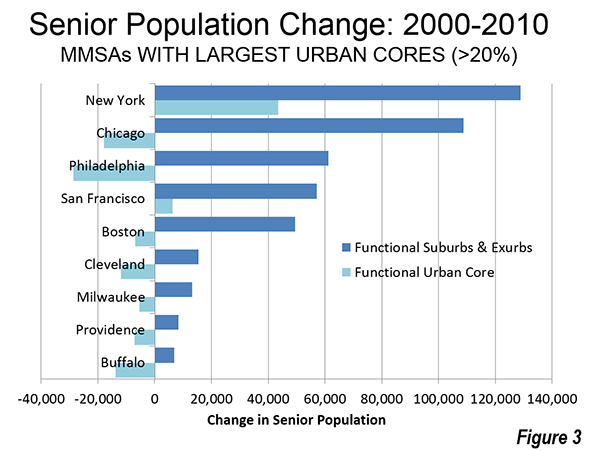

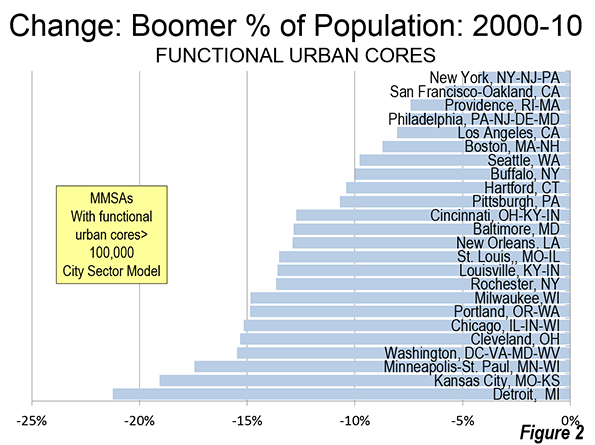

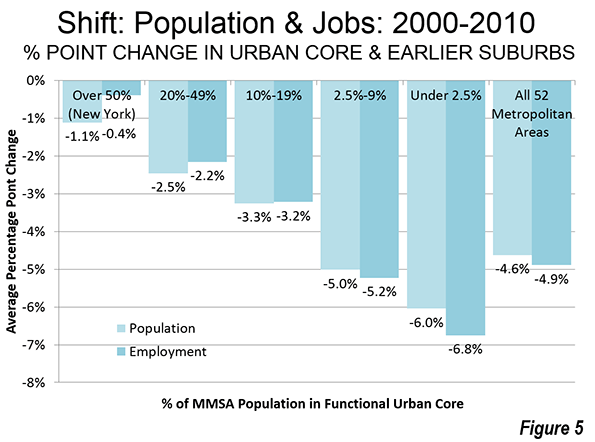

"Job Following" by Relative Urban Core Size

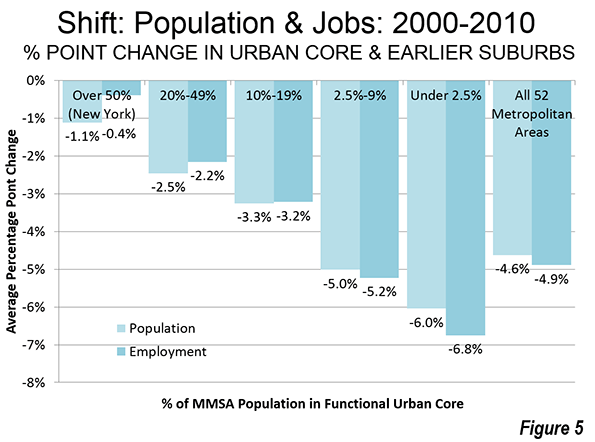

Similar results are obtained when cities are categorized by the population of their urban cores relative to the total city population. Each category indicates an outward shift from the functional urban cores and earlier suburbs to the later suburbs and exurbs, in both the population share and the employment share. However, the shift is less pronounced in the cities with larger relative urban cores, which tend to be in the older urban regions (Figure 5). Out of the 18 cities with functional urban cores amounting to more than 10 percent of the metropolitan area, 16 are in the Northeast (including the Northeastern corridor cities of Washington and Baltimore) and the Midwest, where strong population growth ended long ago.

As usual, New York is in a category by itself, New York, has a functional urban core with more than 50 percent of its population. New York experienced an outward shift of 1.1 percent in its population, and a 0.4 percent outward shift of its employment (the total shift in share, from the urban core and earlier suburbs to the later suburbs and exurbs, expressed in terms of percentage points).

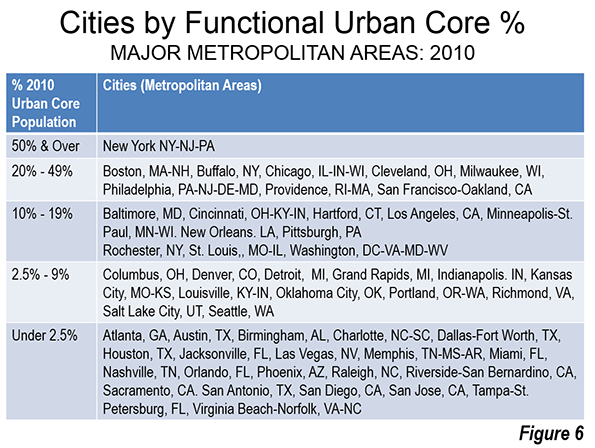

Generally speaking, the stronger the functional urban core, the less the movement of jobs and people from the center. The actual percentages of functional urban core population by city are shown in From Jurisdictional to Functional Analysis of Urban Cores and Suburbs (Figure 6).

On average, there was a shift of nearly five percent from the inner sectors (functional urban cores and earlier suburbs) to the outer sectors (later suburbs and exurbs)

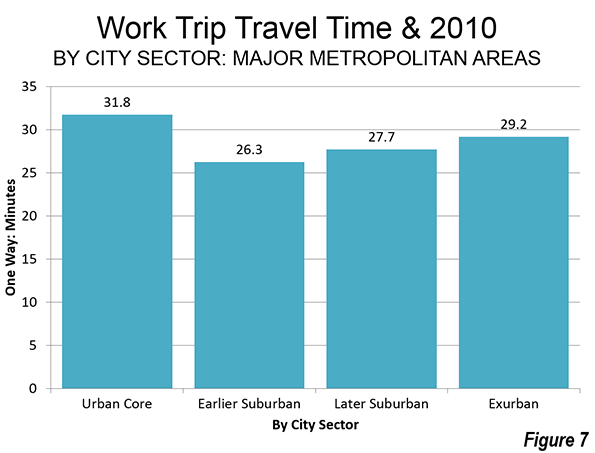

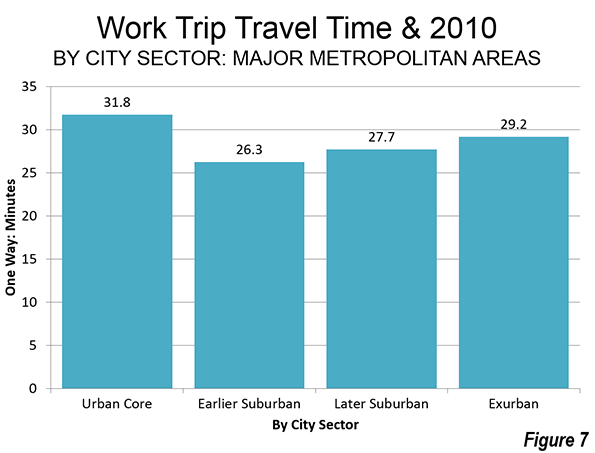

Commute Times: Less Outside the Urban Cores

The earlier suburbs are generally between the functional urban cores and the later suburbs geographically. As a result, jobs are particularly accessible to residents from all over the metropolitan area. A further consequence is that commute times are shortest (26.3 minutes) in the earlier suburbs, where approximately half of the people also live. Commute times are a bit higher in the later suburbs (27.7 minutes). The exurbs have the third longest commutes, at 29.2 minutes. Finally, commute times are longest in the functional urban cores (31.8 percent), both because traffic congestion is greater (to be expected, not least because of their higher densities), and more people take transit, which is slower (Figure 7).

The dispersed, and well coordinated location of jobs and residences is one reason that United States metropolitan areas have shorter commute times and less traffic congestion than its international competitors in Europe, Australia, and Canada. All this is testimony to the effectiveness with which people and the businesses established to serve them have produced effective labor markets, which are the most affluent in the world, in which the transaction related impacts of work trip travel time are less than elsewhere.

Beyond Polycentricity

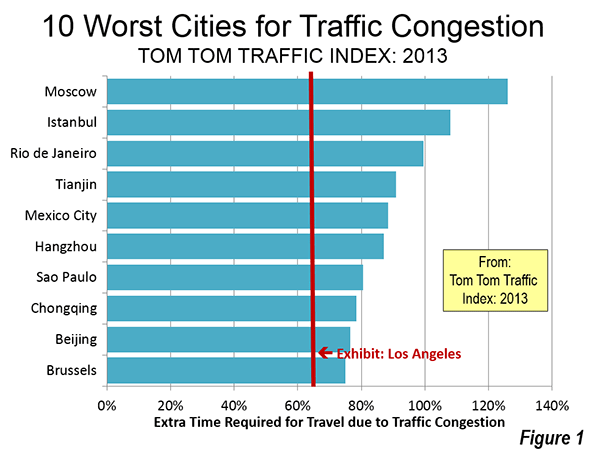

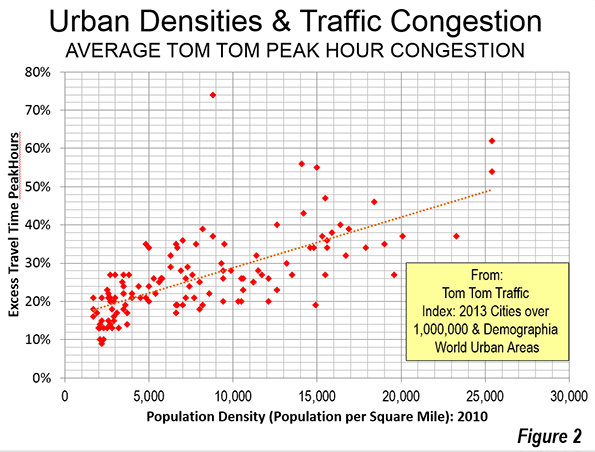

These are not new concepts, despite the continuing tendency to imagine the city as a monocentric organism where everyone works in downtown skyscrapers and lives in suburban dormitories. The lower density US city has not descended into the illusion of suburban gridlock that some planners have declared so stridently. Indeed, traffic congestion is considerably less intense in US cities than it is in the other parts of the high income world for which there is data.

A quarter century ago, University of Southern California economists Peter Gordon and Harry Richardson said that "the co-location of firms and households at decentralized locations has reduced, not lengthened commuting times and distances. Decentralization reduces pressures on the CBD, relieves congestion and avoids ‘gridlock.’" In 1996 they Los Angeles as "beyond polycentricity" Both of these observations fit well as a description of trends in the 2000s. Most US major metropolitan areas are now "beyond polycentricity," not just Los Angeles.

Wendell Cox is principal of Demographia, an international public policy and demographics firm. He is co-author of the “Demographia International Housing Affordability Survey” and author of “Demographia World Urban Areas” and “War on the Dream: How Anti-Sprawl Policy Threatens the Quality of Life.” He was appointed to three terms on the Los Angeles County Transportation Commission, where he served with the leading city and county leadership as the only non-elected member. He was appointed to the Amtrak Reform Council to fill the unexpired term of Governor Christine Todd Whitman and has served as a visiting professor at the Conservatoire National des Arts et Metiers, a national university in Paris.

——

Note 1: The Census Bureau describes "County Business Pattern" data as follows: "Statistics are available on business establishments at the U.S. level and by State, County, Metropolitan area, and ZIP code levels. Data for Puerto Rico and the Island Areas are available at the State and county equivalent levels. County Business Patterns (CBP) covers most NAICS industries excluding crop and animal production; rail transportation; National Postal Service; pension, health, welfare, and vacation funds; trusts, estates, and agency accounts; private households; and public administration. CBP also excludes most establishments reporting government employees.

Note 2: The City Sector Model allows a more representative functional analysis of urban core, suburban and exurban areas, by the use of smaller areas, rather than municipal boundaries. The more than 30,000 zip code tabulation areas (ZCTA) of major metropolitan areas and the rest of the nation are categorized by functional characteristics, including urban form, density and travel behavior. There are four functional classifications, the urban core, earlier suburban areas, later suburban areas and exurban areas. The urban cores have higher densities, older housing and substantially greater reliance on transit, similar to the urban cores that preceded the great automobile oriented suburbanization that followed World War II. Exurban areas are beyond the built up urban areas. The suburban areas constitute the balance of the major metropolitan areas. Earlier suburbs include areas with a median house construction date before 1980. Later suburban areas have later median house construction dates.

Urban cores are defined as areas (ZCTAs) that have high population densities (7,500 or more per square mile or 2,900 per square kilometer or more) and high transit, walking and cycling work trip market shares (20 percent or more). Urban cores also include non-exurban sectors with median house construction dates of 1945 or before. All of these areas are defined at the zip code tabulation area (ZCTA) level.

—–

Photo: Beyond Polycentric Houston (by author)