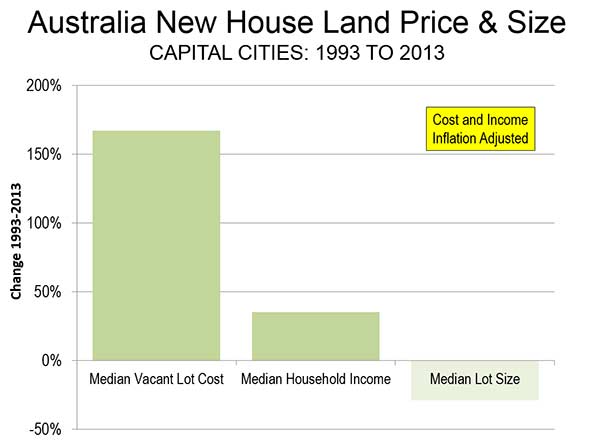

For seven decades urban planners have been seeking to force higher urban population densities through urban containment policies. The object is to combat "urban sprawl," which is the theological (or ideological) term applied to the organic phenomenon of urban expansion. This has come at considerable cost, as house prices have materially increased relative to incomes, which is to be expected from urban containment strategies that ration land (and thus raise its price, all things being equal).

Smart Growth America is out with its second report that rates urban sprawl, with the highest scores indicating the least sprawl and the lowest scores indicating the most (Measuring Sprawl 2014).

Metropolitan Areas and Metropolitan Divisions

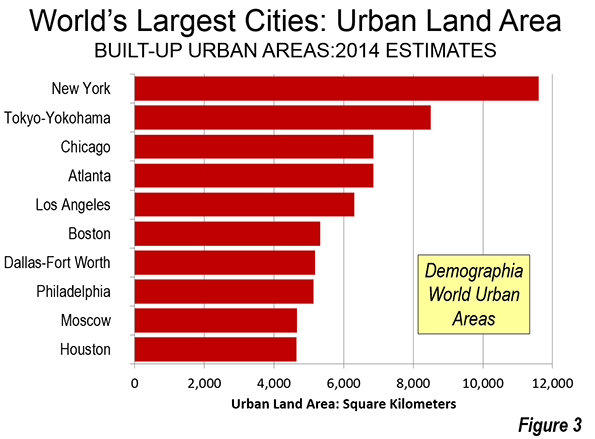

For the second time in a decade Smart Growth America has assigned a "sprawl" rating to what it calls metropolitan areas. I say "what it calls," because, as a decade ago, the new report classifies "metropolitan divisions" as metropolitan areas (Note 1). Metropolitan divisions are parts of metropolitan areas. This is not to suggest that a metropolitan division cannot have a sprawl index, but metropolitan divisions have no place in a ranking of metropolitan areas. Worse, metropolitan areas with metropolitan divisions were not rated (New York, Los Angeles, Chicago, Dallas-Fort Worth, Philadelphia, Washington, Miami, San Francisco, Detroit, and Seattle).

This year’s highest rating among 50 major metropolitan areas (over 1,000,000 population) goes to part of the New York metropolitan area (the New York-White Plains-Wayne metropolitan division) at 203.36. The lowest rating (most sprawling) is in Atlanta, at 40.99. This contrasts with 2000, when the highest rating was in part of the New York metropolitan area (the New York PMSA), at 177.8, compared to the lowest, in the Riverside-San Bernardino PMSA portion of the since redefined Los Angeles metropolitan area, at 14.2. Boston is excluded due to insufficient data (Note 2)

Rating Sprawl

The sprawl ratings are interesting, though obviously I would have done them differently.

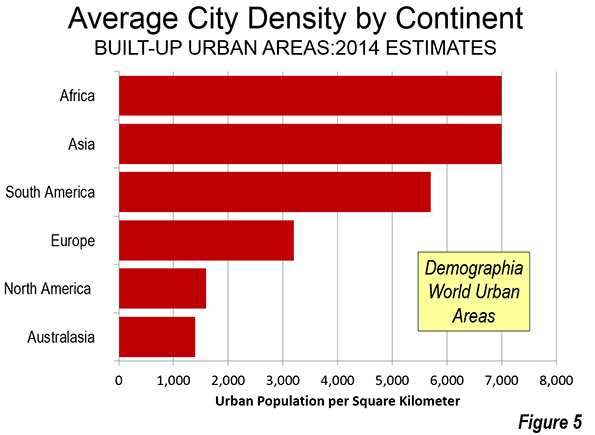

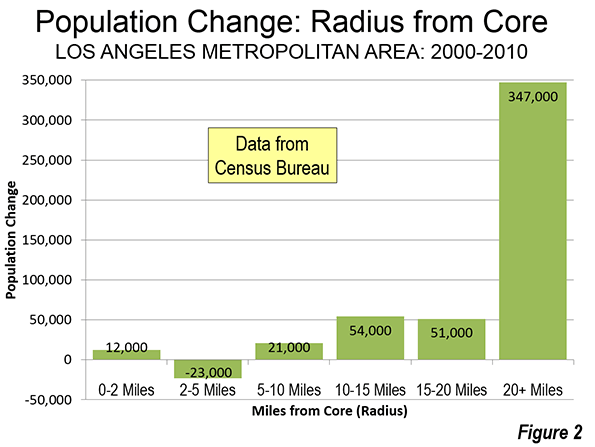

Overall urban population density would seem to be a more reliable indicator (called urbanized areas in the United States, built-up urban areas in the United Kingdom, population centres in Canada, and urban areas just about everywhere else). For example, the Los Angeles metropolitan area (combining its two component metropolitan divisions), has an index indicating greater sprawl than Springfield, Illinois. Yet, the Los Angeles urban area population density is about four times that of Springfield (6,999 residents per square mile, compared to 1747 per square mile, approximately the same as bottom ranking Atlanta). The implication is that if Los Angeles were to replicate the individual ratings that make up its index, and covered (sprawled) over four times as much territory, it would be less sprawling than today.

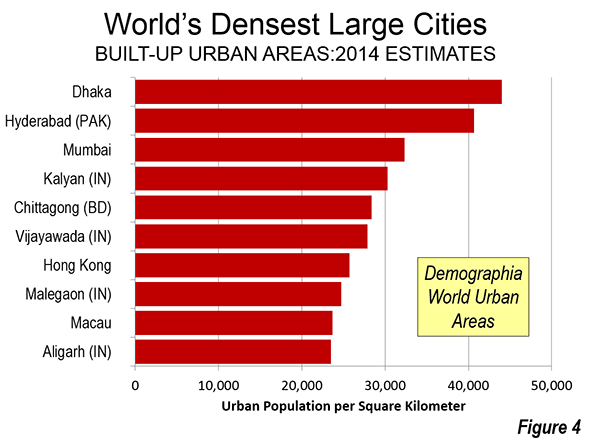

This case simply illustrates the fact that sprawl has never been well defined. Indeed, the world’s most dense major urban area, Dhaka (Bangladesh), with more than 15 times the urban density of Los Angeles and 65 times the urban density of Springfield, has been referred to in the planning literature as sprawling.

Housing Affordability

The principal problem with the report lies with its assertions regarding housing affordability. Measuring Sprawl 2014 notes that less sprawling areas have higher housing costs than more sprawling areas (Note 3). However, it concludes that the lower costs of transportation offset much more all of the difference. This conclusion arises from reliance the US Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) and US Department of Transportation (DOT) Location Affordability Index, which bases housing affordability for home owners on median current expenditures, not the current cost of buying the median priced home. Nearly two thirds of the nation’s households are home owners, and most aspire to be.

HUD-DOT describes its purpose as follows:

"The goal of the Location Affordability Portal is to provide the public with reliable, user-friendly data and resources on combined housing and transportation costs to help consumers, policymakers, and developers make more informed decisions about where to live, work, and invest."

Yet, a consumer relying on the Location Affordability Index could be seriously misled. The HUD-DOT index (Note 4) does not begin to tell the story to people seeking to purchase homes. The costs are simply out of pocket housing costs, regardless of whether the mortgage has been paid off and regardless of when the house was bought (urban containment markets have seen especially strong house price increases).An index including people who have no mortgage and people who have lower mortgage payments as a result of having purchased years ago cannot give reliable information to consumers in the market today.

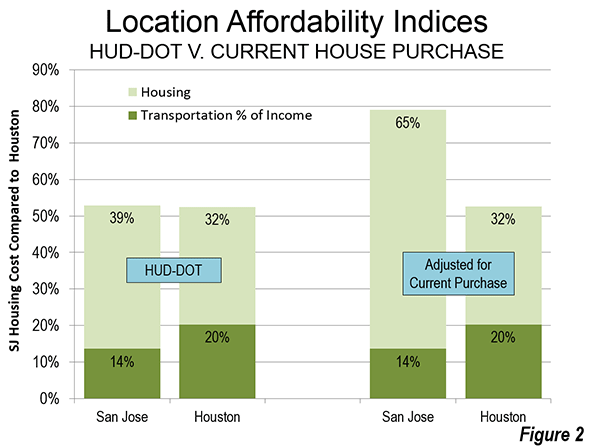

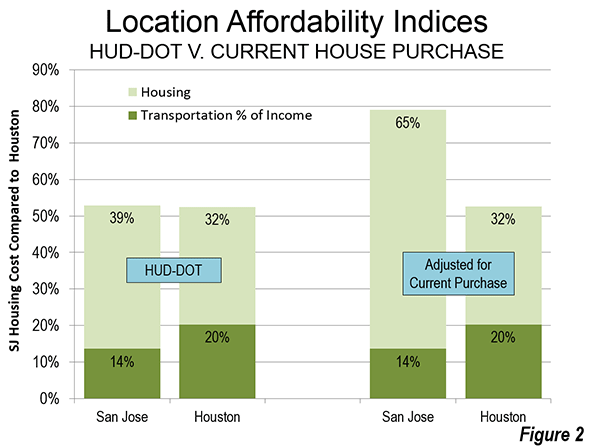

A household relying on this source of information would be greatly misled. For example, comparing Houston with San Jose, according to HUD-DOT, owned housing and transportation consume virtually the same share of the median household income in each of the two metropolitan areas. In Houston, 52.5 percent of income is required for housing and transportation, while the number is marginally higher than San Jose (52.9 percent).

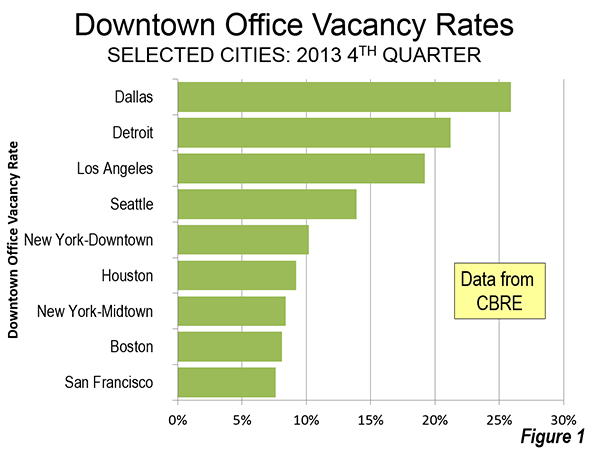

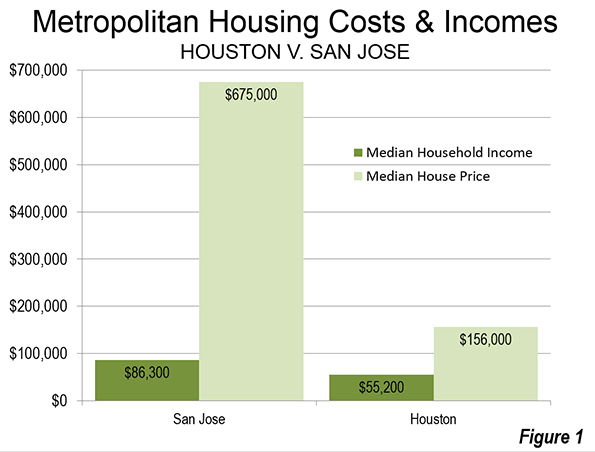

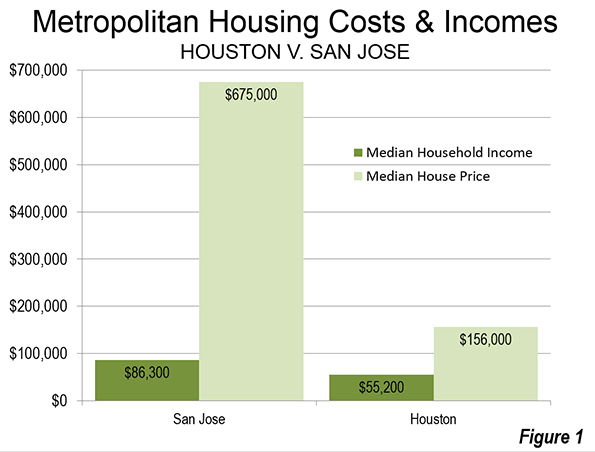

But the HUD-DOT numbers reflect nothing like the actual costs of housing in San Jose relative to Houston. The median price house in Houston was approximately $155,000, 2.8 times the median household income of $55,200 (this measure is called the median multiple) during the 2006-10 period used in calculating the HUD-DOT index. In San Jose, the median house price was approximately $675,000, 7.8 times the median household income of $86,300 (Figure 1).

If the Location Affordability Index reflected the real cost for a prospective home owner (HUD-DOT costs including a market rate mortgage for the house), a considerable difference would emerge between San Jose and Houston. The combined San Jose Location Affordability Index for home owners would rise to 85 percent of median household income, a full 60 percent above the Houston figure, rather than the minimal difference of less than one percent indicated by HUD-DOE (Figure 2).

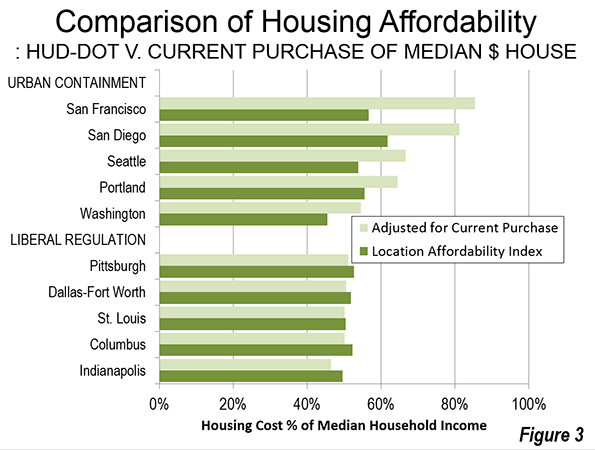

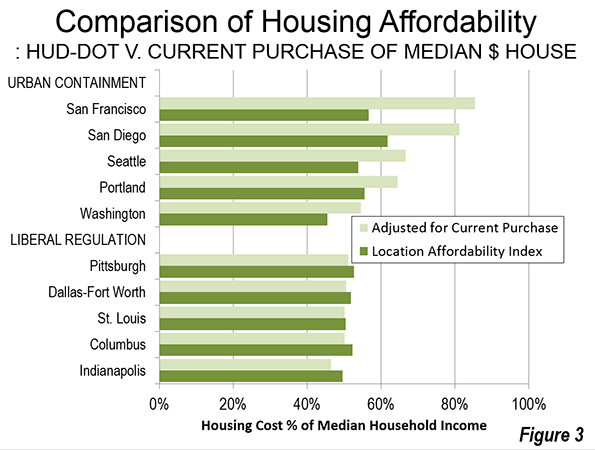

Under-Estimating the Cost of Urban Containment

There is a substantial difference between the HUD–DOT housing and transportation cost and the actual that would be paid by prospective buyers. Five selected urban containment markets indicate a substantially higher actual housing cost than reflected in the HUD–DOT figures. On the other hand, in the selected liberally regulated markets (or traditionally regulated markets), the HUD–DOE figure is much closer to the current cost of home ownership (Figure 3). This is a reflection of the greater stability (less volatility) of house prices in liberally regulated markets. Overall, based on data in the 50 major metropolitan areas, owned housing costs relative to incomes rise approximately 6 percent for each 10 percent increase in the sprawl index – that is, less sprawl is associated with higher house prices relative to incomes (Note 6).

The increasing impacts of urban containment’s housing cost increases have been limited principally to households who have made recent purchases. The effect will become even more substantial in the years to come as the turnover of the more expensive housing stock continues.

Granted, the 2006 to 2010 housing data includes part of the housing bubble and its higher house prices. However, house prices relative to incomes have returned to levels at or above that recorded during the period covered by Measuring Sprawl 2014 in "urban containment" markets, such as San Francisco, San Jose, Los Angeles, San Diego, Seattle, Portland, and Washington.

Economic Mobility and Human Behavior

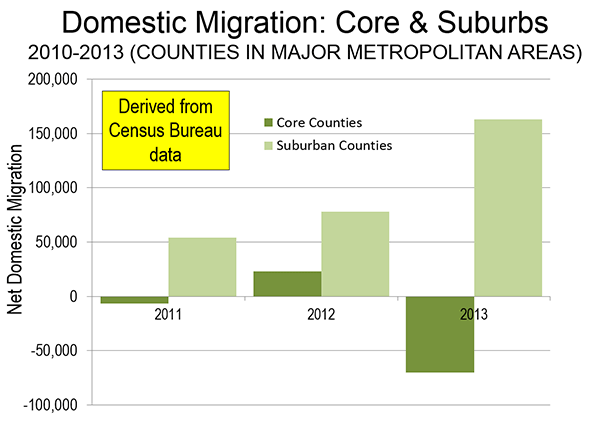

Another assertion requires attention: economic mobility is greater in less sprawling metropolitan areas. The basis is research by Raj Chetty and Nathaniel Hendren of Harvard University and Patrick Kline and Emmanuel Saez of the University of California, Berkeley. However, the realities of domestic migration suggest caution with respect to the upward mobility conclusions, as is indicated in Distortions and Reality About Income Mobilityand in commentary by Columbia University urban planner David King.

Virtually all urban history shows city growth to have occurred as people have moved to areas offering greater opportunity. Jobs, not fountains, theatres and art districts, drive nearly all the growth of cities. This means that there should be a strong relationship between the cities net domestic migration and the economic mobility conclusions of the research. The strongest examples show the opposite relationship.

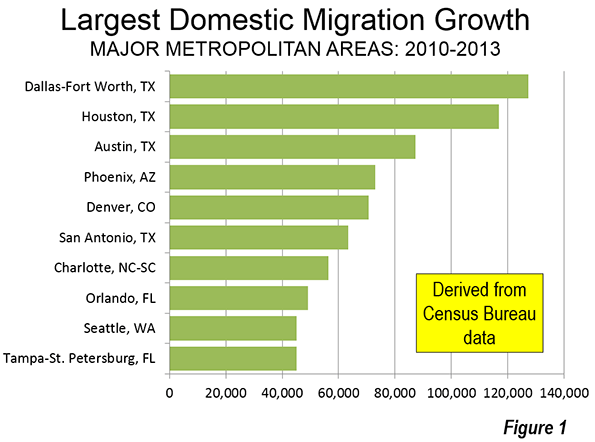

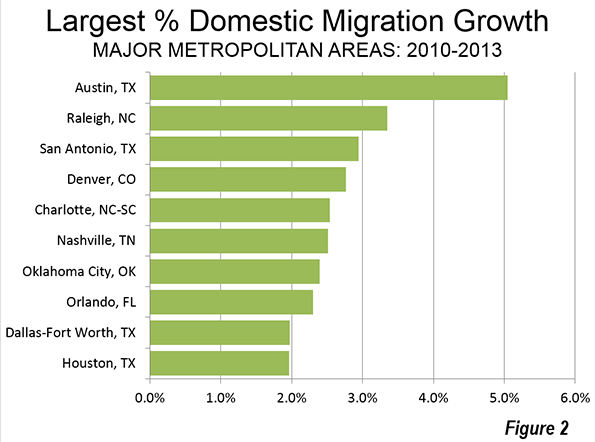

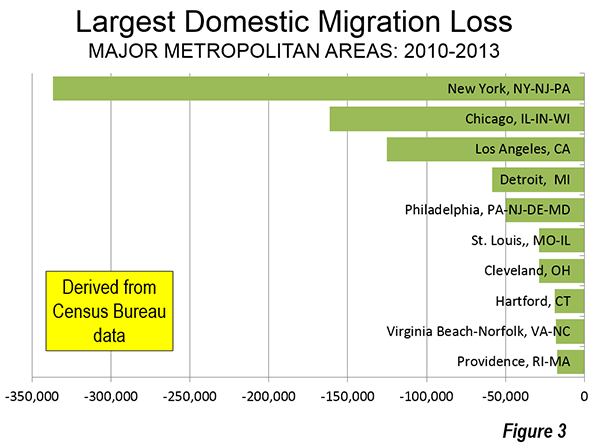

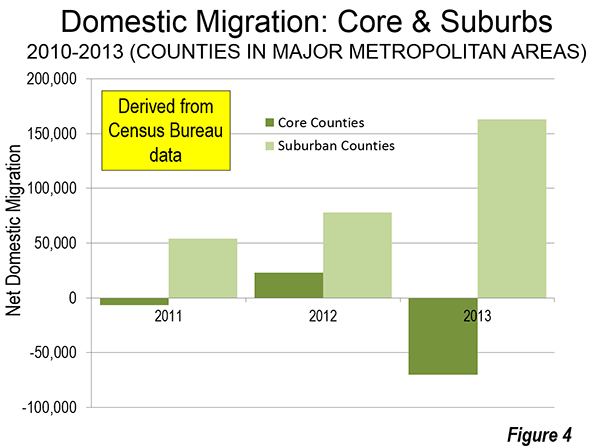

Domestic migration is strongly away from some metropolitan areas identified in the research as having the greatest upward income mobility also had substantial net domestic migration losses. For example, despite claims of high economic mobility New York, Los Angeles and the San Francisco Bay area, each lost approximately 10 percent of their population to net domestic migration in the 2000s. On the other hand, some metropolitan areas scoring the lowest in upward economic mobility drew substantial net domestic migration gains. For example, low economic mobility Charlotte and Atlanta gained 17 percent and 10 percent due to net domestic migration in the 2000s. Thus, the results of the economic research appear to be inconsistent with expected human behavior (Note 7).

Sprawl: An Inappropriate Priority

The new sprawl report is just another indication that urban planning policy has been elevated to a more prominent place than appropriate among domestic policy priorities. The usual justification for urban containment is a claimed sustainability imperative for its densification and anti-mobility policies. Yet, these policies are hugely expensive and thus ineffective at reducing greenhouse gas emissions, and thus have the potential to unduly retard economic growth (read "the standard of living and job creation"). Far more cost-effective alternatives are available, which principally rely on technology.

There is a need to reverse this distortion of priorities. Little, if anything is more fundamental than improving the standard of living and reducing poverty (see Toward More Prosperous Cities). Housing is the largest element of household budgets and policies of that raise its relative costs necessarily reduce discretionary incomes (income left over after paying taxes and paying for basic necessities). There is no legitimate place in the public policy panoply for strategies that reduce discretionary incomes.

London School of Economics Professor Paul Cheshire may have said it best, when he noted that urban containment policy is irreconcilable with housing affordability.

———

Note 1: The previous Smart Growth America report used primarily metropolitan statistical areas (PMSAs), which have been replaced by metropolitan divisions. The primary metropolitan statistical areas were also subsets of metropolitan areas (labor market areas). This is problem is best illustrated by the fact that the Jersey City PMSA, composed only of Hudson County, NJ, is approximately one mile across the Hudson River from Manhattan in New York. Manhattan is the world’s second largest central business district and frequent transit service connects the two. Obviously, Jersey City is a part of the New York metropolitan area (labor market area), not a separate labor market.

Note 2: Because of incomplete data, Boston is not given a sprawl rating in Measuring Sprawl 2014. A different rating system in the previous edition resulted in a Boston rating among the least sprawling. Yet, the Boston metropolitan area is characterized by low density development. Outside a 10 mile radius from downtown, the population density within the urban area is slightly lower than that of Atlanta (same square miles of land area used).

Note 3: Higher house prices relative to household incomes are more associated with policies to control urban sprawl (such as urban growth boundaries and other land rationing devices), than with the extent of sprawl. More compact (less sprawling) urban areas do not necessarily have materially higher house prices. For example, in 1970, the Los Angeles urban area was one of the most dense in the United States, yet it was within the historical affordability range (a median multiple of less than 3.0). The emergence of Los Angeles as the nation’s most dense urban area in the succeeding decades (and 30 percent increase in density) is largely the result of a change in urban area criteria. Through 1990, the building blocks of urban areas were municipalities, which meant that many square miles of San Gabriel Mountains wilderness were included, because it was in the city of Los Angeles. Starting in 2000, the building blocks or urban areas became census blocks, which are far smaller and thus exclude the large swaths of rural territory that were included before in some urban areas.

Note 4: The transport costs from the Location Affordability Index are accepted for the purposes of this article.

Note 5: The current purchase housing cost is based on the average price to income multiple over the period of 2006 to 2010, relative to the median household income (calculated from quarterly data from the Joint Center for Housing Studies of Harvard University, State of the Nation’s Housing 2011). It is assumed that the buyer would finance 90 percent of the house cost at the average 30 year fixed mortgage rate with points over the period. The 10 percent down payment is allocated annually in equal amounts over the 360 months (30 years). The final annual cost estimate is calculated by adding the monthly mortgage payment and down payment allocation to the median monthly housing cost in each metropolitan area for households without a mortgage.

HUD-DOT uses the "selected monthly owner cost" from the American Community Survey (ACS) for its cost of home ownership. According to ACS, “Selected monthly owner costs are calculated from the sum of payment for mortgages, real estate taxes, various insurances, utilities, fuels, mobile home costs, and condominium fees."

Note 6: This is based on a two-variable regression estimation (log-log) with the sprawl index as the independent variable and the substituted housing share of income as the dependent variable for the 50 largest metropolitan areas (excluding Boston), It is posited that most of the variation in housing costs is accounted for by variation in land costs. Other significant factors, such as construction costs and financing costs in this sample vary considerably less. A sprawl index for each metropolitan areas represented by metropolitan divisions (not provided in the sprawl report) is estimated by population weighting.

Note 7: Another difficulty with that research is that it measured geographic economic mobility at age 30, well before people reach their peak earning level. This is likely to produce less than reliable results, since those who achieve the highest incomes as well as the most educated such as medical doctors and people with advanced degrees) are likely to have larger income increases after age 30 than other workers.

Wendell Cox is principal of Demographia, an international public policy and demographics firm. He is co-author of the “Demographia International Housing Affordability Survey” and author of “Demographia World Urban Areas” and “War on the Dream: How Anti-Sprawl Policy Threatens the Quality of Life.” He was appointed to three terms on the Los Angeles County Transportation Commission, where he served with the leading city and county leadership as the only non-elected member. He was appointed to the Amtrak Reform Council to fill the unexpired term of Governor Christine Todd Whitman and has served as a visiting professor at the Conservatoire National des Arts et Metiers, a national university in Paris.

Suburban neighborhood photo by Bigstock.