The term “Greater New York” was applied, unofficially, to the 1898 consolidation that produced the present city of New York, which brought together the present five boroughs (counties). The term “Greater” did not stick, at least for the city. When consolidated, much of the city of New York was agricultural. As time went on, the term "Greater" came to apply to virtually any large city and its environs, not just New York and implied a metropolitan area or an urban area extending beyond city limits. By 2010, Greater New York had expanded to somewhere between 19 million and 23 million residents, depending on the definition.

Greater New York’s population growth has been impressive. Just after consolidation, in 1900, the city and its environs had 4.2 million residents, according to Census historian Tertius Chandler. Well before all of the city’s farmland had been developed, New York, including its environs, had become the world’s largest urban area by the 1920s, displacing London from its 100 year predominance. Yet, even when Tokyo displaced New York in the early 1960s, there was still farmland on Staten Island.

New York became even larger in two dimensions, as a result of geographic redefinitions arising from the 2010 census.

The Expanding New York Metropolitan Area

The New York metropolitan area grew by enough land area to add more than 700,000 residents between 2000 and 2010, even after the decentralization reported upon in the metropolitan area as defined in 2000. The expansion of the metropolitan area occurred because the employment interchange between the central counties and counties outside the metropolitan area in 2000 became sufficient to expand the boundaries by more than 1,000 square miles (2,500 square kilometers).

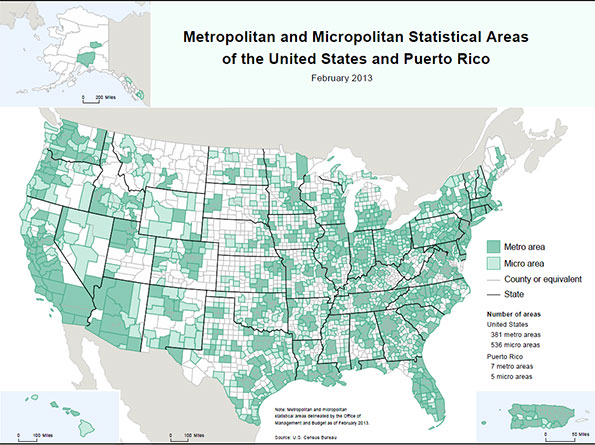

Summarized, metropolitan areas are developed by identifying the largest urban area (area of continuous urban development with 50,000 or more population) and then designating the counties that contain this urban area as “central counties.” Additional (“outlying”) counties are included in a metropolitan area if 25 percent or more of their resident workers have jobs in the central counties, or if 25 percent or more of the employees in the outlying county live in the central counties (There are additional criteria, which can be reviewed at 2010 Office of Management and Budget metropolitan area standards). In addition, adjacent metropolitan areas can be merged into a combined statistical area at a lower level of employment interchange (see below).

For example, one of the counties added to the New York metropolitan area in the 2010 redefinition was Dutchess (home of the Franklin Delano Roosevelt Presidential Library). A resident of Dutchess County who works across the county line in Putnam County (a central county) would count toward the 25 percent employment interchange with the central counties of the New York metropolitan area. Contrary to some perceptions, metropolitan areas do not denote an employment interchange between suburban areas and a central city, even as major an employment destination as the city of New York.

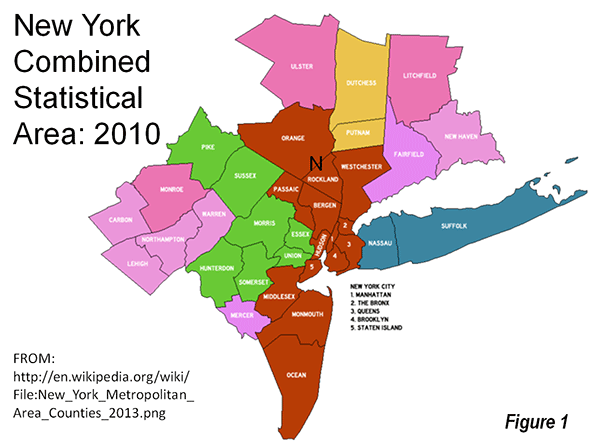

The OMB concept of “central” counties is in contrast to the more popular view that would consider the central counties to be Manhattan (New York County) or the five boroughs of New York City. In fact, out of the New York metropolitan area’s 25 counties, all but three (Dutchess and Orange in New York and Pike in Pennsylvania) are central counties. Sufficient parts of the urban area are in the other 22 counties, which makes them central.

The Expanding New York Combined Statistical Area

OMB has a larger metropolitan concept called the "combined statistical area." The combined statistical area is composed of metropolitan and micropolitan areas that have a high degree of economic integration with the larger metropolitan area. Essentially, adjacent areas are merged into a combined statistical area if there is an employment interchange of 15 percent. This occurs where the sum of the following two factors is 15 percent or more: (1) The percentage of resident workers in the smaller area employed in the larger area (not just central counties) and (2) The percentage of workers employed in the smaller area who reside in the larger area.

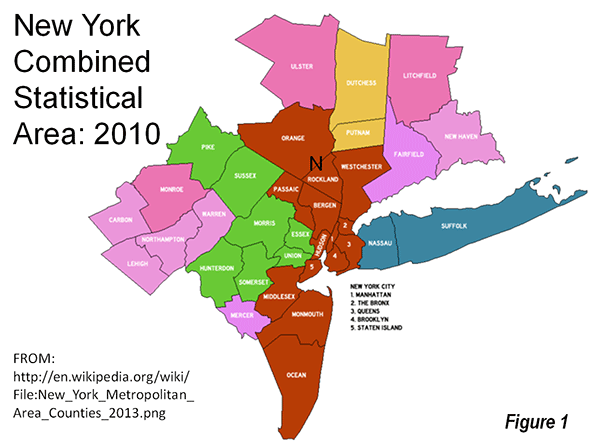

On this measure, New York became greater by more 1 million residents as a result of the changes in commuting patterns. The addition of Allentown (Pennsylvania – New Jersey) and the East Stroudsburg, Pennsylvania metropolitan areas expanded the New York combined statistical area by another 2,700 square miles (7,000 square miles), bringing the population to 23.1 million. Altogether, the metropolitan area and combined area land area increases added up to 3,700 square miles (9,700 square kilometers). The 35 county New York combined statistical area is illustrated in the map (Figure 1).

Organized Around the World’s Largest Urban Area (in Land Area)

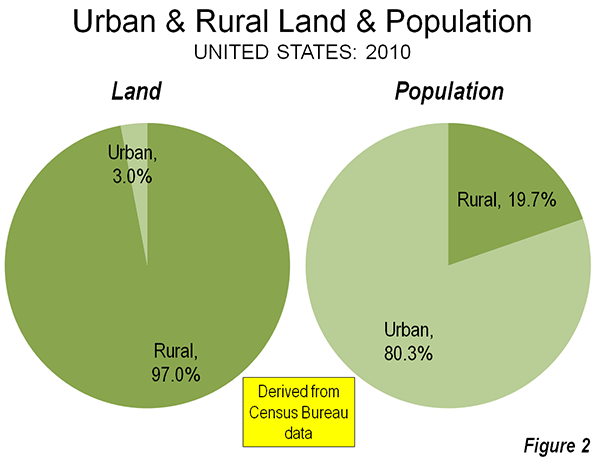

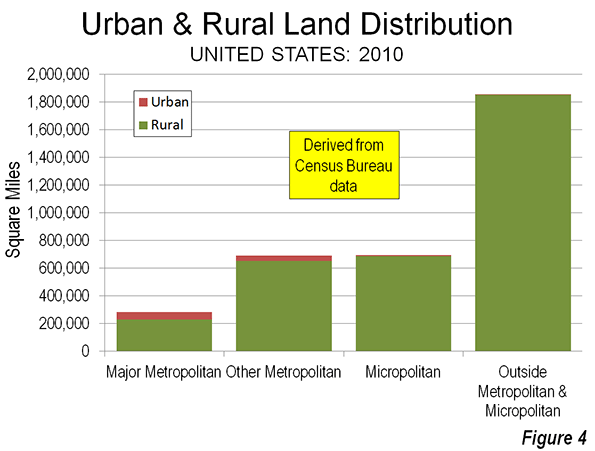

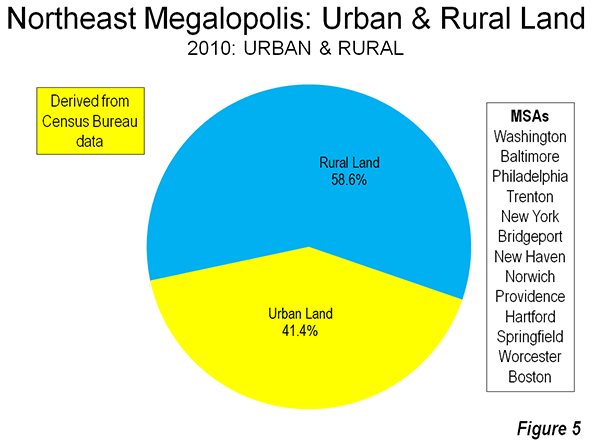

The New York combined statistical area is very large. It covers approximately 14,500 square miles (37,600 square kilometers). From north to south, it measures 235 miles (375 kilometers) from the Massachusetts border of Litchfield County, Connecticut to Beach Haven, in Ocean County, New Jersey. It is an even further east to west, at more than 250 miles (400 kilometers) from Montauk State Park in Suffolk County, New York to the western border of Carbon County in Pennsylvania (Note 2). Despite containing the largest urban area in the world, at 4,500 square miles (11,600 square kilometers), more than 60 percent of the combined statistical area is rural (see Rural Character in America’s Metropolitan Areas).

Dispersion of Jobs and Residences

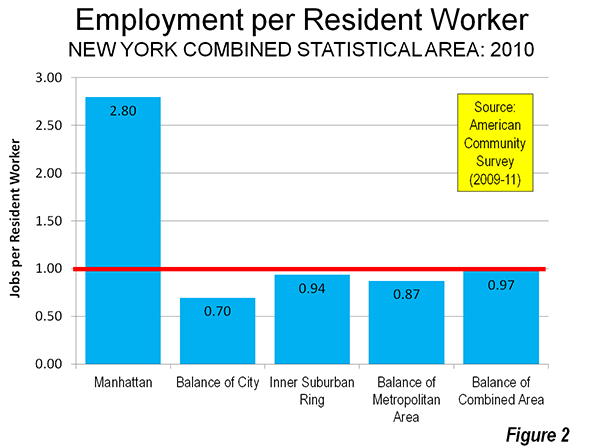

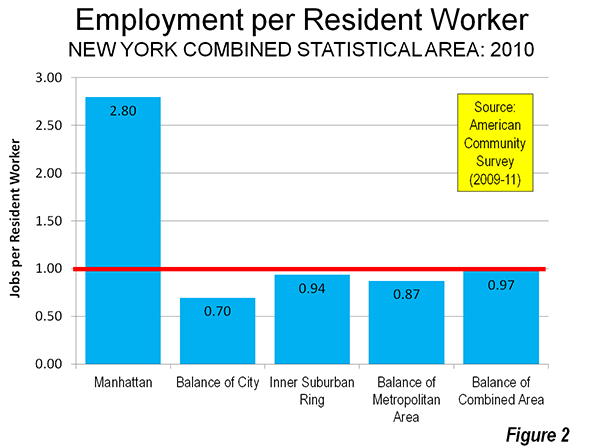

The dispersion characteristic of modern metropolitan regions is illustrated by the extent to which jobs have followed the population in the New York combined statistical area. In all “rings” outside the city of New York, there is near parity between resident workers and jobs. The greatest employment to worker parity (0.97) is in the metropolitan and micropolitan areas outside the New York metropolitan area (Allentown, PA-NY; Bridgeport, CT; East Stroudsburg, PA; New Haven, CT; Torrington, CT; and Trenton, NJ). There is 0.94 parity in the inner ring suburban counties, which include Nassau and Westchester in New York as well as Bergen, Essex, Hudson, Middlesex, Passaic and Union in New Jersey. The outer balance of the New York metropolitan area has slightly lower employment to worker parity, at 0.87 (Figure 2).

The lowest employment to worker parity in the New York combined statistical area is in the four boroughs of New York City outside Manhattan, at 0.70. The greatest disparity is in Manhattan, where there are 2.80 jobs for every resident worker. Combining all of New York’s five boroughs yields a much more balanced 1.17 jobs per resident worker.

Example: Commuting from Hunterdon County

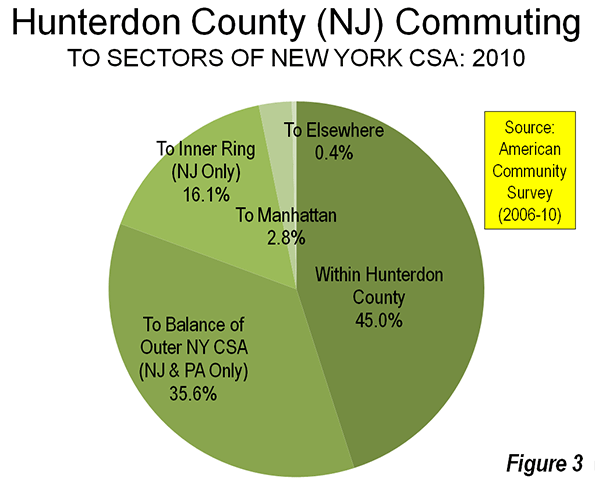

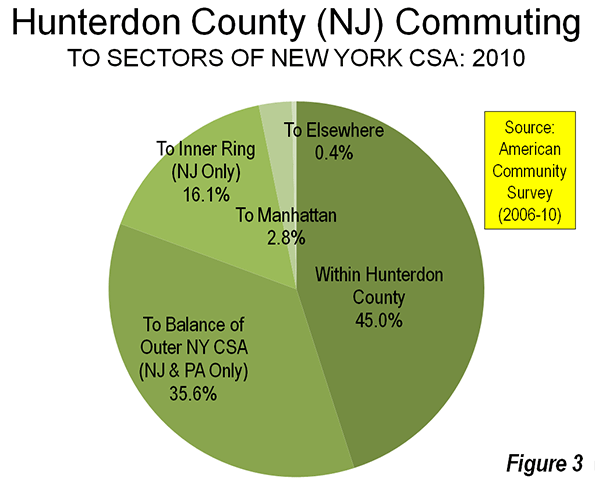

Hunterdon County, New Jersey provides an example of the dispersion of employment in the New York area. Hunterdon County is located at the edge of the New York metropolitan area. It is well served by the commuter rail services of New Jersey Transit. With a line that reaches Penn Station in New York City, approximately 55 miles (35 kilometers) away. Yet, the world’s second largest employment center (after Tokyo’s Yamanote Loop), Manhattan south of 59th Street, draws relatively few from Hunterdon County to fill its jobs.

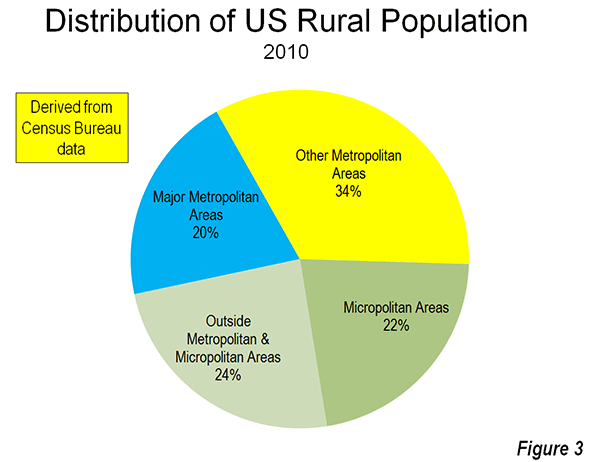

Among resident workers, 45 percent have jobs in Hunterdon County. Another 36 percent work in other outer counties of the combined statistical area. This leaves only 19 percent of workers who commute to the rest of the combined statistical area. The New Jersey inner suburban counties attract 16 percent of Hunterdon’s commuters and Manhattan employs just three percent of Hunterdon’s resident workers (Figure 3). Fewer than 0.5 percent of Hunterdon’s commuters work in the balance of the CSA, including the outer boroughs of New York, the other New York counties and Connecticut). The detailed area definitions are included in the Table.

| DISTRIBUTION OF COMMUTING FROM HUNTERDON COUNTY, NEW JERSEY |

| To Locations in the New York Combined Statistical Area (2006-2010) |

| NY CSA Sector |

Commuting from Hunterdon County |

Areas Included |

| Hunterdon County |

45.0% |

Hunterdon County, NJ |

| Outer Combined Statistical Area |

35.6% |

Monmouth County, NJ |

| Morris County, NJ |

| Ocean County, NJ |

| Pike County, PA |

| Somerset County, NJ |

| Sussex County, NJ |

| Allentown metropolitan area, PA-NJ |

| East Stroundsburg metropolitan area, PA |

| Trenton metropolitan area, NJ |

| Inner Ring (New Jersey only) |

16.1% |

Bergen County, NJ |

| Essex County, NJ |

| Hudson County, NJ |

| Middlesex County, NJ |

| Passaic County, NJ |

| Union County, NJ |

| Manhattan |

2.8% |

New York County, NY |

| Elsewhere |

0.4% |

Bronx |

| Brooklyn |

| Queens |

| Staten Island |

| Dutchess County, NY |

| Nassua County, NY |

| Orange County, NY |

| Putnam County, NY |

| Rockland County, NY |

| Suffolk County, NY |

| Westchester County, NY |

| Bridgeport metropolitan area, CT |

| Kingston metropolitan area, NY |

| New Haven metropolitan area, CT |

| Torrington metropolitan area, CT |

From Commuter Belts and Concentricity to Dispersion

Metropolitan areas are labor markets, as OMB reminds in its 2010 metropolitan standards, which refer to metropolitan areas, micropolitan areas, and combined statistical areas as geographic entities associated with at least one core plus “adjacent territory that has a high degree of social and economic integration with the core as measured by commuting ties. ”

Yet metropolitan areas have changed a great deal. Through the middle of the last century, metropolitan areas were perceived as monocentric with core cities and a surrounding “commuter belt” from which the city drew workers to fill its jobs. However, metropolitan areas have become more polycentric, as Joel Garreau showed in his book Edge City: Life on the New Frontier. In more recent years, metropolitan areas have become even more dispersed, with most employment located in areas that are hardly centers at all. Of course, some people still commute to downtown and edge cities. Others work even further away, but most find their employment much closer to home. That is the story of New York and, which has just become greater, and other metropolitan areas as well.

——

Note 1: OMB revised its metropolitan terms in 2000. The term “core based statistical area” (CBSA) is used to denote metropolitan areas (organized about urban areas of 50,000 population or more) and micropolitan areas (organized around urban areas of 10,000 to 50,000 population). The former “consolidated metropolitan statistical area,” was replaced by the combined statistical area, which is a combination of core based statistical areas. OMB also notes that the term “urban area” includes “urbanized areas” (50,000 population or more) and “urban clusters (10,000 to 50,000 population).

Note 2: Part of the reason for this large geographic expanse is the use of counties as building blocks of core based statistical areas. If the smaller geographic units were used (such as census blocks, as in the delineation of urban areas), the geographies would be smaller, though populations would be similar.

——-

Wendell Cox is a Visiting Professor, Conservatoire National des Arts et Metiers, Paris and the author of “War on the Dream: How Anti-Sprawl Policy Threatens the Quality of Life.

Photograph: 59th Street, Manhattan (by author).