New data from the American Community Survey makes it possible to review the trend in mode of access to employment in the United States over the past five years. This year, 2012, represents the fifth annual installment of complete American Community Survey data. This is also a significant period, because the 2007 was a year before the Lehman Brothers collapse that triggered the Great Financial crisis, while gasoline prices increased about a third between 2007 and 2012.

National Trends

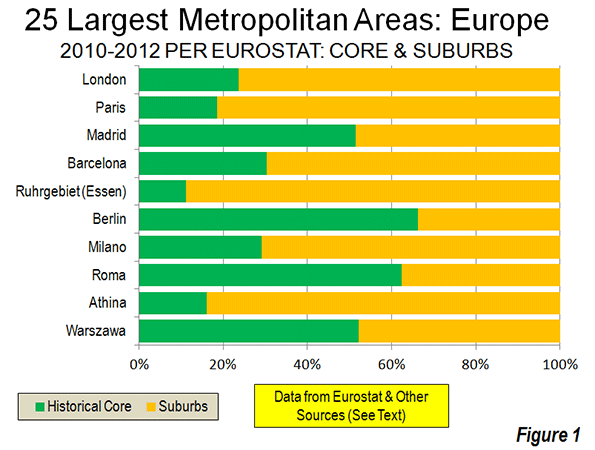

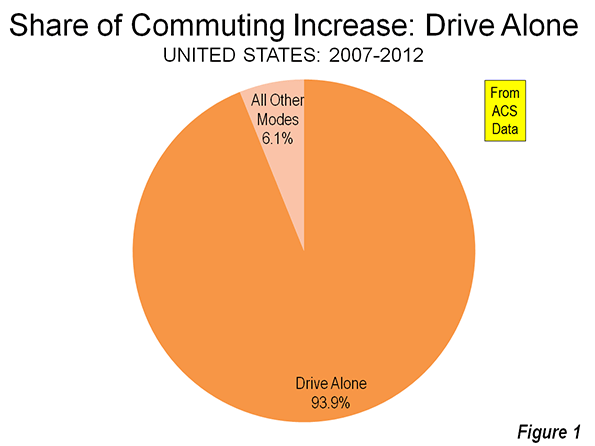

The work trip access data is shown in Tables 1 and 2. Driving alone continued to dominate commuting, as it has since data was first reported in the 1960 census. In 2007, 76.1 percent of employment access was by driving alone, a figure that rose to 76.3 percent in 2012. Between 2007 and 2012, driving alone accounted for 94 percent of the employment access increase, capturing 1.55 million out of the additional 1.60 million daily one-way trips (Figure 1). The other 50,000 new transit commutes were the final result of increases in working at home, transit and bicycles, minus losses in car pooling and other modes.

Carpools continued to their long decline, losing share in 43 of the 52 major metropolitan areas. Approximately 810,000 fewer people travel to work by carpools in 2012, which reduced its share from 10.7 percent to 9.7 percent.

Transit did better, rising from 4.9 percent of work access in 2007 to 5.0 percent in 2012. There was an overall increase of approximately 250,000 transit riders. This increase, however, may be less than might have anticipated in view of the much higher gasoline prices and the imperative for commuters to save money in a more difficult economy.

Bicycling also did well, rising from a 0.5 percent share in 2007 to a 0.6 percent share in 2012. Approximately 200,000 more people commuted by bicycle by 2012.

Walking retained its 2.8 percent share, with only a modest 15,000 increase over the period. The largest increase in employment access outside single occupant driving was working at home, which rose from 4.1 percent to 4.4 percent. This translated into an increase of approximately 470,000.

Metropolitan Area Highlights

Among the 52 metropolitan areas with more than 1 million population (major metropolitan areas), 47 had drive alone market shares of 70 percent or more. Birmingham was the highest, at 85.6 percent. Surprisingly, this grouping included metropolitan areas with reputations for strong transit ridership, such as Chicago, Philadelphia, and Portland. Four metropolitan areas had drive alone shares of between 60 percent and 70 percent: Seattle, Washington, Boston, and San Francisco, which had the second lowest in the nation at 60.8 percent. As would be expected, New York had by far the lowest drive alone market share at 50.0 percent.

Consistent with its low drive alone market share, New York led by a large margin the other metropolitan areas in its transit work trip market share. Transit carried 31.1 percent of New York commuters, up nearly a full percentage point from the 30.2 percent in 2007. New York alone accounted for nearly one-half of the growth in transit commuting over the period.

San Francisco continued to hold onto second place, with a 15.1 percent transit market share, up a full percentage point from 2007. Washington rose to 14.0 percent, up from 13.2 percent in 2007. Boston (11.9 percent) and Chicago (11.0 percent) were the only other major metropolitan areas to achieve a transit work trip market share of more than 10 percent, and were little changed from 2007.

Working at home continued to increase at a larger percentage rate than any other mode of work access. Four metropolitan areas were tied for the top position in 2012, at 6.4 percent. These included Raleigh, Austin, San Diego, and Portland, all metropolitan areas with a strong high-tech orientation. In San Diego and Portland, where large light rail systems have been developed, working at home is now more popular as a mode of access to work than transit.

According to 2012 US Census Bureau estimates, the major metropolitan areas comprised 55.2 percent of the national population. These metropolitan areas represented a slightly larger share of total employment, at 57.3 percent. The combined major metropolitan areas also had similar shares to their national population share in each of the employment access modes, ranging from a low of 55.3 percent of communters driving alone to 59.9 percent of walkers. The one exception was transit, where the major metropolitan areas constituted nearly all of commuters, at 90.7 percent, well above their 55.2 percent share of US population (Table 1).

| Table 1 | ||||||||

| Distribution of Employment Access (Commuting) by Employment Location: 2012 | ||||||||

| SHARE OF WORK ACCESS BY MODE (2012) | ||||||||

| All Employment | Drive Alone | Car Pool | Transit | Bike | Walk | Other | Work at Home | |

| MAJOR METROPOLITAN AREAS | 57.3% | 55.3% | 55.4% | 90.7% | 59.9% | 56.0% | 55.6% | 59.3% |

| Metropolitan Areas with Legacy Cities | 17.1% | 13.8% | 14.4% | 65.4% | 21.5% | 27.8% | 18.3% | 17.1% |

| 6 Legacy Cities (see below) | 6.0% | 2.7% | 4.1% | 55.1% | 12.7% | 16.3% | 7.8% | 4.6% |

| Suburban | 11.1% | 11.1% | 10.3% | 10.3% | 8.8% | 11.5% | 10.5% | 12.6% |

| New York Metropolitan Area | 6.4% | 4.2% | 4.5% | 39.6% | 5.8% | 13.6% | 8.5% | 5.9% |

| Legacy City: New York | 3.1% | 1.0% | 1.5% | 35.4% | 4.2% | 9.5% | 4.2% | 2.5% |

| Suburban | 3.3% | 3.2% | 3.0% | 4.2% | 1.7% | 4.1% | 4.3% | 3.5% |

| 5 Other Metropolitan Areas with Legacy Cities | 10.7% | 9.6% | 9.9% | 25.8% | 15.7% | 14.2% | 9.8% | 11.2% |

| 5 Legacy Cities (CHI, PHI, SF, BOS, WDC) | 2.9% | 1.7% | 2.6% | 19.7% | 8.5% | 6.8% | 3.6% | 2.1% |

| Suburban | 7.8% | 7.9% | 7.3% | 6.1% | 7.1% | 7.5% | 6.2% | 9.1% |

| 46 Other Major Metropolitan Areas | 40.2% | 41.5% | 41.0% | 25.3% | 38.4% | 28.2% | 37.3% | 42.2% |

| OUTSIDE MAJOR METROPOLITAN AREAS | 42.7% | 44.7% | 44.6% | 9.3% | 40.1% | 44.0% | 44.4% | 40.7% |

| United States | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% |

| Calculated from American Community Survey: 2012 (one year) | ||||||||

Follow this link to a table containing data for the nation’s major metropolitan areas.

Commuting Becomes More Concentrated in Legacy Cities

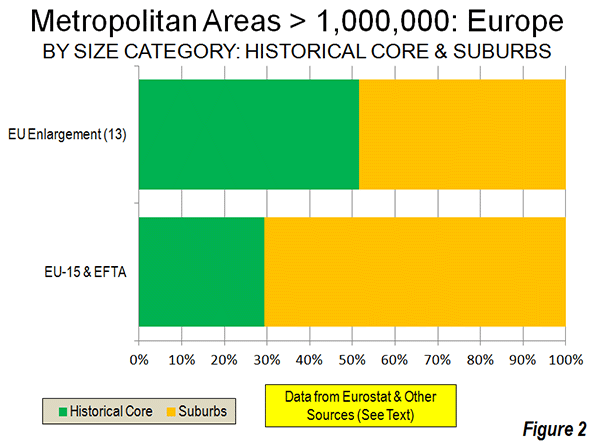

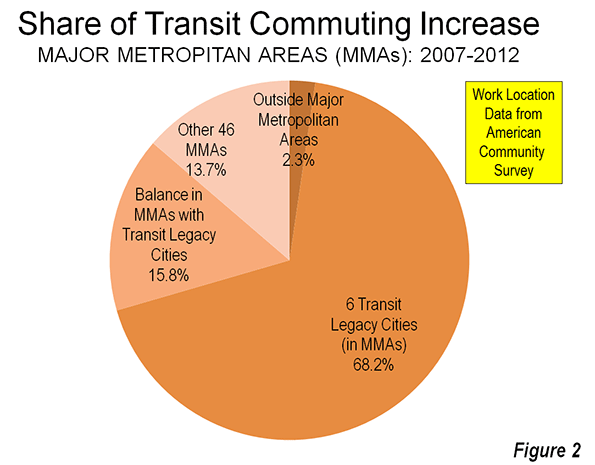

This concentration of transit commuting was most evident to the six large "transit legacy cities," (the core cities of New York, Chicago, Philadelphia, San Francisco, Boston, and Washington), which still exhibit sufficient remnants of their pre-automobile urban cores that support extraordinarily high transit market shares. The transit legacy cities accounted for 55 percent of all transit commuting destinations in the United States, yet have only six percent of the nation’s jobs. Between 2007 and 2012, the concentration increased, with transit legacy cities accounting 68 percent of the additional transit commutes were between 2007 and 2012. Outside the legacy cities, there was relatively little difference in the share of transit commutes within metropolitan areas with legacy cities and in the other major metropolitan areas (Figure 2)

The key to the intensive use of transit in the legacy cities is the small pockets of development that are particularly amenable to high transit market shares – the six largest downtown areas (central business districts) in the United States. Most of the commuting to transit legacy cities is to these downtown areas, Yet, the geographical areas of these downtowns is very small. Combined, the six downtown areas are only one-half larger than the land area of Chicago’s O’Hare International Airport. This yields employment per square mile densities of from 40 to 150 times densities of employee residences throughout their respective urban areas.

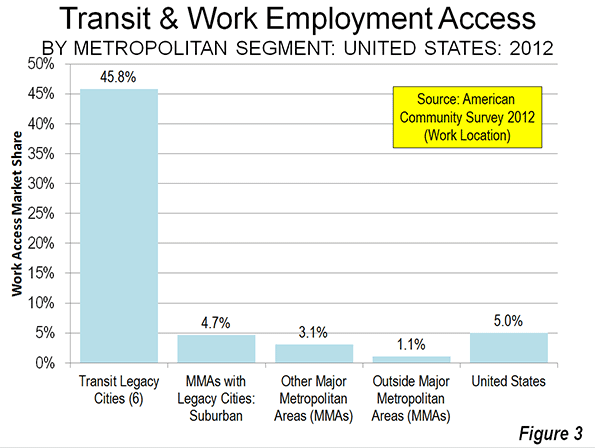

Not surprisingly, transit has very strong market shares to work locations in the transit legacy cities, at 45.8 percent. At the same time, transit commuting to locations outside the transit legacy cities is generally well below the national average. The exception is New York, where transit commuting to suburban locations is 6.4 percent, above the overall national average of 5.0 percent. In the five other metropolitan areas with transit legacy cities, transit commuting to suburban locations is 3.9 percent. This drops to 3.1 percent, overall, in the 46 other major metropolitan areas and 1.1 percent in the rest of the nation (Table 2 and Figure).

| Table 2 | |||||||

| Employment Access (Commuting) by Employment Location: 2012 | |||||||

| Drive Alone | Car Pool | Transit | Bike | Walk | Other | Work at Home | |

| MAJOR METROPOLITAN AREAS | 73.6% | 9.4% | 7.9% | 0.6% | 2.8% | 1.2% | 4.5% |

| Metropolitan Areas with Legacy Cities | 61.7% | 8.2% | 19.2% | 0.8% | 4.6% | 1.3% | 4.4% |

| 6 Legacy Cities (see below) | 33.9% | 6.5% | 45.8% | 1.3% | 7.6% | 1.6% | 3.3% |

| Suburban | 76.8% | 9.1% | 4.7% | 0.5% | 2.9% | 1.1% | 5.0% |

| New York Metropolitan Area | 50.0% | 6.8% | 31.1% | 0.6% | 6.0% | 1.6% | 4.1% |

| Legacy City: New York | 23.7% | 4.6% | 57.1% | 0.8% | 8.6% | 1.6% | 3.5% |

| Suburban | 74.8% | 8.9% | 6.4% | 0.3% | 3.5% | 1.6% | 4.6% |

| 5 Other Metropolitan Areas with Legacy Cities | 68.6% | 9.0% | 12.1% | 0.9% | 3.7% | 1.1% | 4.6% |

| 5 Legacy Cities (CHI, PHI, SF, BOS, WDC) | 44.8% | 8.6% | 33.7% | 1.8% | 6.5% | 1.5% | 3.1% |

| Suburban | 77.6% | 9.1% | 3.9% | 0.6% | 2.7% | 1.0% | 5.1% |

| 46 Other Major Metropolitan Areas | 78.7% | 9.9% | 3.1% | 0.6% | 2.0% | 1.1% | 4.6% |

| OUTSIDE MAJOR METROPOLITAN AREAS | 79.9% | 10.1% | 1.1% | 0.6% | 2.9% | 1.3% | 4.2% |

| United States | 76.3% | 9.7% | 5.0% | 0.6% | 2.8% | 1.2% | 4.4% |

| Transit legacy cities include the municipalities of New York, Chicago, Philadelphia, San Francisco, Boston & Washington | |||||||

Staying the Same

The big news in the last five years of commuting data is that virtually nothing has changed. This is remarkable, given the greatest economic reversal in 75 years and continuing gasoline price increases that might have been expected to discourage driving alone. Yet, driving alone continues to increase, while the most cost effective mode of car pooling continued to suffer huge losses, while working at home continued to increase strongly.

Wendell Cox is a Visiting Professor, Conservatoire National des Arts et Metiers, Paris and the author of “War on the Dream: How Anti-Sprawl Policy Threatens the Quality of Life.

Photograph: DART light rail train in downtown Dallas (by author)