Around the fifth century BCE, Athens may have been the most important city in the West. Like China’s Chang’an (modern Xi’an), the "on and off" capital of China, Athens has experienced many severe "ups and downs" throughout its remarkable history. At its ancient peak, Athens is estimated to have had more than 300,000 residents (historic population estimates vary greatly). At least one estimate indicates that Athens may have fallen to a population of under 5,000 by the middle 19th century. The city, now having evolved into the modern manifestation of the metropolitan area (Attica region), peaked at 3.9 million in the early 2000s, but its population has begun to drop again.

Athens is the capital of Greece and located at the south end of the Attica peninsula, on the Aegean Sea. The core municipality of Athens is located approximately 5 miles (8 kilometers) from the historic port of Piraeus, from which ferries operate to the Greek Islands.

Metropolitan Dispersion

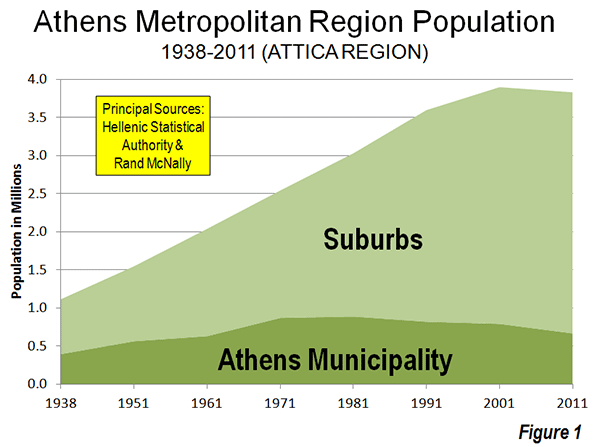

Like virtually all of the world’s metropolitan areas, population growth has been concentrated in the suburbs and exurbs for decades.

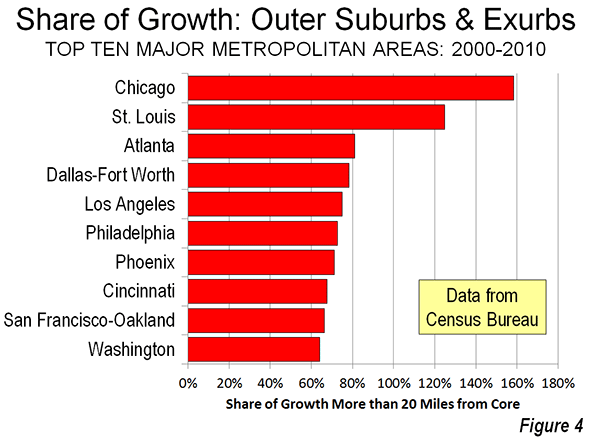

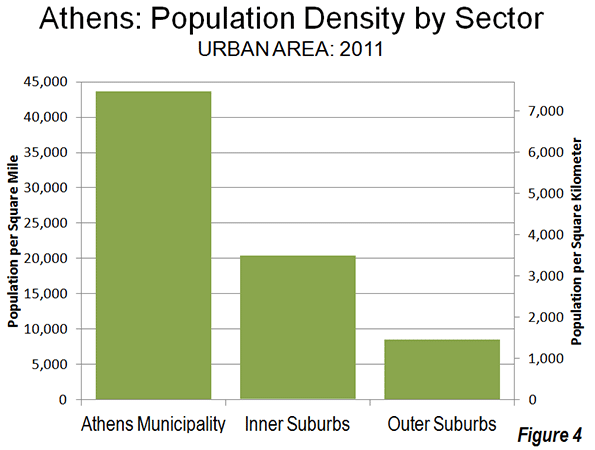

The Athens municipality (the historic core city) peaked at 885,000 in 1981. At a population density of nearly 60,000 per square mile (23,000 per square kilometer), Athens once stood among the most dense municipalities in the world. However, the Athens municipality since has declined, with population losses in each of the three subsequent decades. Between 2001 and 2011, the population fell 125,000 to 664,000, a decline of 16%. The Athens municipality is still dense, however, at 44,000 per square mile (17,000 per square kilometer). The rest of the urban organism, as is usually the case, is considerably less so.

Photo: Athens Core Density

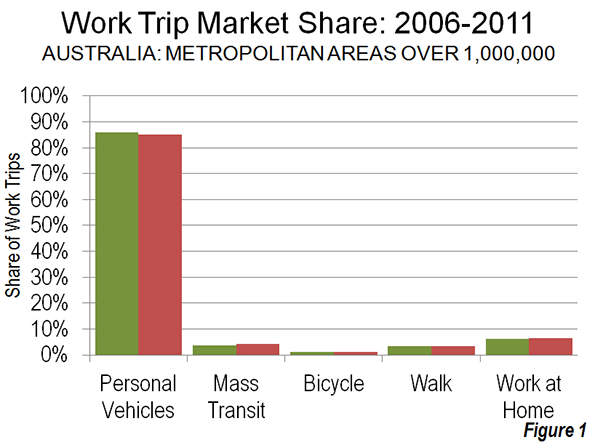

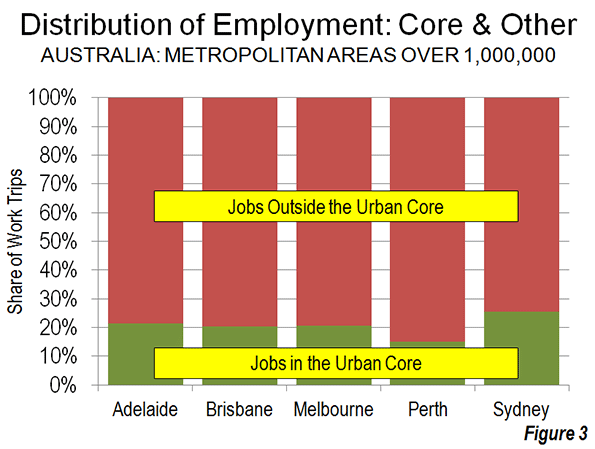

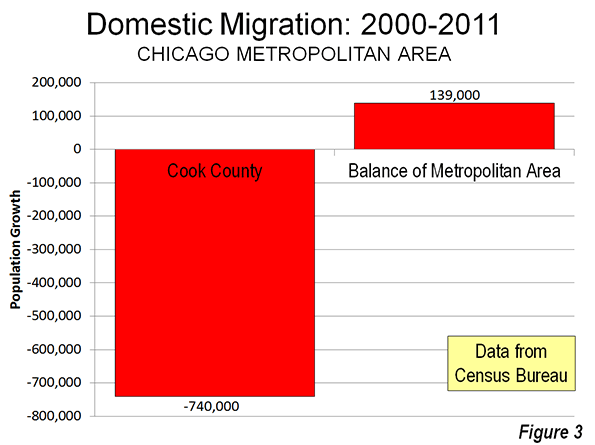

Since 1951, suburban and exurban Athens (see The Evolving Urban Form Series Definitions) has accounted for 95% of the growth in the metropolitan region, adding 2.2 million new residents, compared to approximately 100,000 for the Athens municipality. Since 1971, all of the population growth has been in the suburbs and exurbs (Figure 1).

However, over the last decade, population growth has dropped across the entire Athens metropolitan region. Certainly, the low Greek fertility rate is a factor (see The Rise of Post-Familialism: Humanity’s Future?). Greece’s total fertility rate (average number of children per women of child bearing age) is approximately 1.5, according to Eurostat, well below the replacement rate of 2.1 not to mention the 2.3 Greek figure in the late 1970s. More recently, it is likely that the Greek fiscal crisis has contributed to an even lower rate of increase by reducing the previously flow of international migration as well as discouraging family formation among native Greeks.

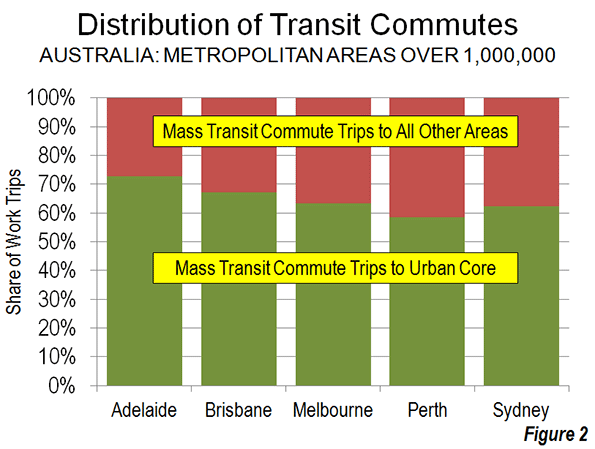

Athens growth slowed dramatically well before the financial crisis. Between 1991 and 2001, the Athens metropolitan region added approximately 300,000 new residents. But between 2001 and 2011, the metropolitan region lost 67,000 residents. However, the suburbs and exurbs gained marginally, adding 58,000 residents, partially offsetting the loss in the Athens municipality (Figure 2). Even so, the suburban population increase was miniscule compared to the 330,000 gain of the previous decade (photo: North Suburban Athens).

Photo: North Suburban Athens

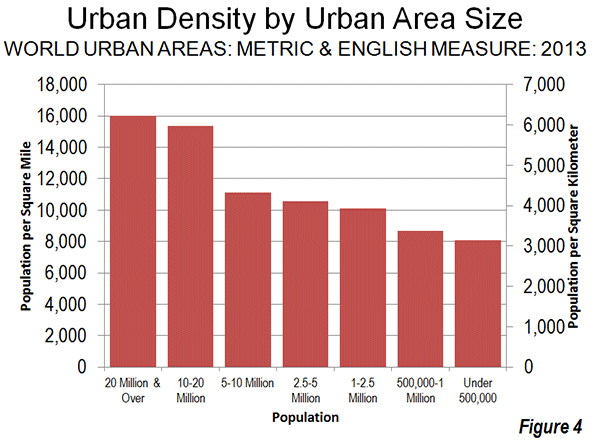

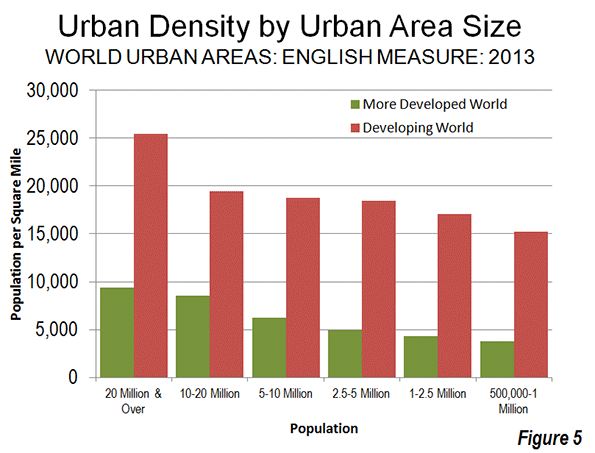

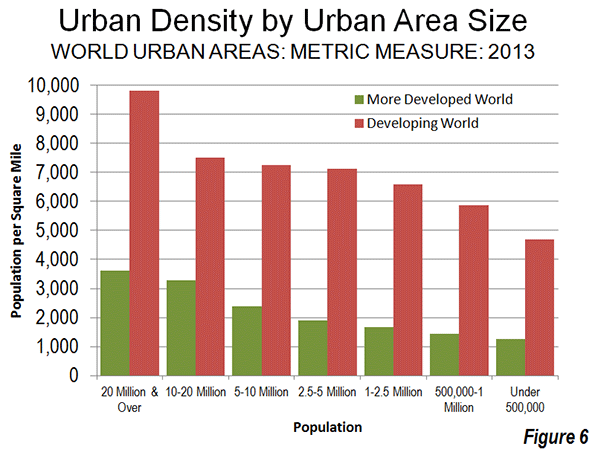

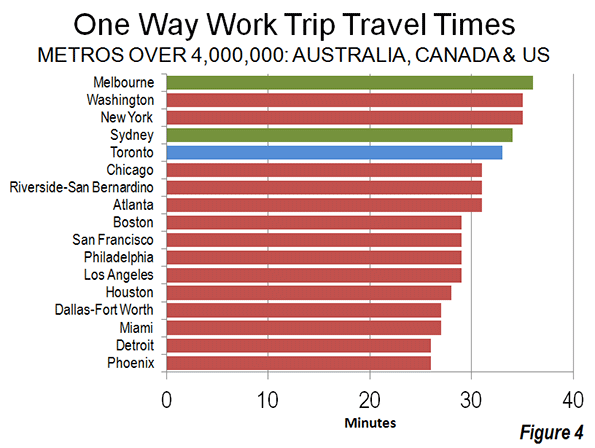

The Urban Area

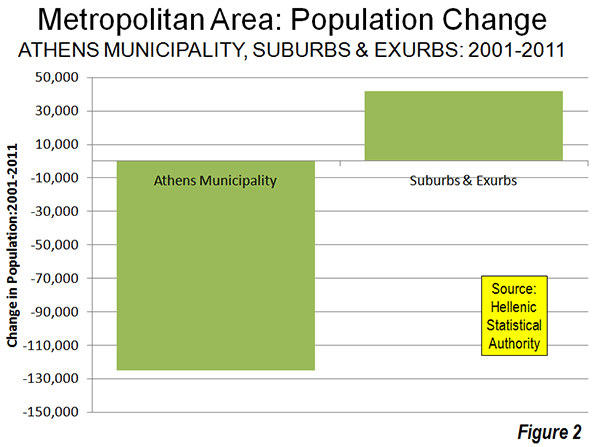

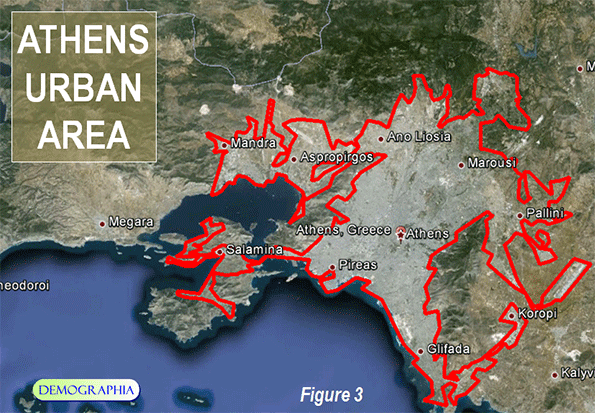

Even with its slow and even negative growth, the Athens urban area remains among the most dense in the developed world (Figure 3). No major urban area in Western Europe, Japan or the New World (Australia, Canada, New Zealand and the United States) is as dense. The 2013 edition of Demographia World Urban Areasindicates that the Athens urban area has a population of 3.5 million (Note), living in a land area of 225 square miles (580 square kilometers), for a density of 15,600 per square mile (6,000 per square kilometer). This places Athens slightly ahead of London (15,300 per square mile or 5,900 per square kilometer), about double the density of Toronto or Los Angeles and more than four times that of Portland.

As is typical around the world, the urban area of Athens exhibits a generally declining density from the core to the urban fringe. From the 44,000 per square mile (17,000 per square kilometer) Athens municipality density, the inner suburbs drop to approximately 20,000 per square mile (7,700 per square kilometer). This is still a high population density for inner suburbs, reflecting the fact that much of the area was developed before the broad achievement of automobile ownership (a similar situation is obvious in the inner ring suburbs of Paris). The outer ring suburbs have been more shaped by the automobile, yet have a density of 8,500 per square mile (3,300 per square kilometer), which still is high by Western European standards (Figure 4).

Affluence

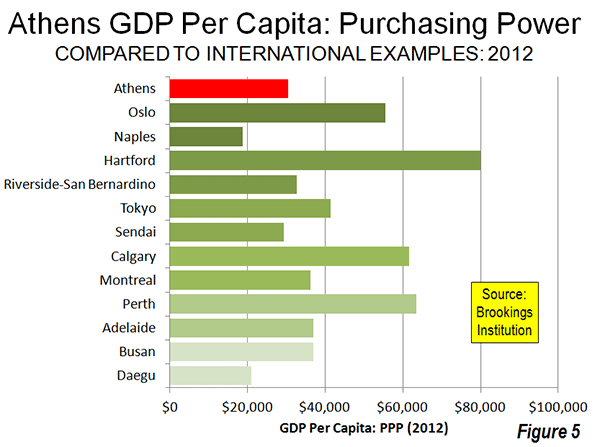

Athens has below average affluence among the metropolitan regions of the developed world. According to data in the Brookings Institution Global Metro-Monitor, Athens had a gross domestic product, purchasing power parity adjusted (GDP-PPP) per capita of $30,500 in 2012. This trails the most affluent metropolitan regions around the more developed world. It is less than one-half the gross domestic product per capita of Hartford (US), the world’s most affluent major urban area ($79,900). The Athens GDP-PPP is approximately one-half that of regional leaders Perth (Australia) at $63,400, Calgary ($61,100), Tokyo ($41,400) and Busan (South Korea) at $36.900. Athens also ranks well below Western Europe’s most affluent metropolitan region, Oslo, at $55,500. Athens is also less affluent than the least major metropolitan areas with the lowest GDP-PPPs per capita in Australia (Adelaide), Canada (Montréal), and the United States (Riverside-San Bernardino). However, Athens has a higher GDP-PPP per capita than Sendai (Japan), Daegu (South Korea) and Naples (Figure 5), the least affluent major metropolitan areas in their respective geographies.

Low Fertility, Declining Migration and An Uncertain Future

Even as the national fertility rate dropped in the late 20th century, Athens continued to grow strongly due largely to international migration, especially from Albania. During the 1990s, virtually all of the population growth in Greece was the result of immigration, as the natural components of growth (births minus deaths) fell into decline. During the 2000s, immigration declined so severely that the nation lost population, most of it in the Athens metropolitan region (with the Athens municipality’s loss exceeding the nation’s) where the foreign born population has concentrated. Much of the decline in international migration resulted from the severe economic crisis.

Athens typically exhibits the principal function of cities in civilization. When cities compete well by facilitating economic aspiration, they grow. When they do not, cities stagnate or fall into decline. For Athens, stagnation or decline seems the likely scenario in the foreseeable future.

Wendell Cox is a Visiting Professor, Conservatoire National des Arts et Metiers, Paris and the author of “War on the Dream: How Anti-Sprawl Policy Threatens the Quality of Life.

—–

Note: The difference between the metropolitan area and urban area population is the residents living in exurban areas (outside the urban area, but within the metropolitan area).

Photo: The Acropolis (all photos by author)