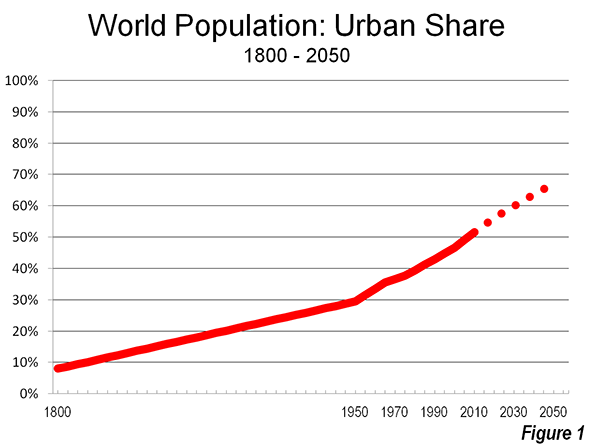

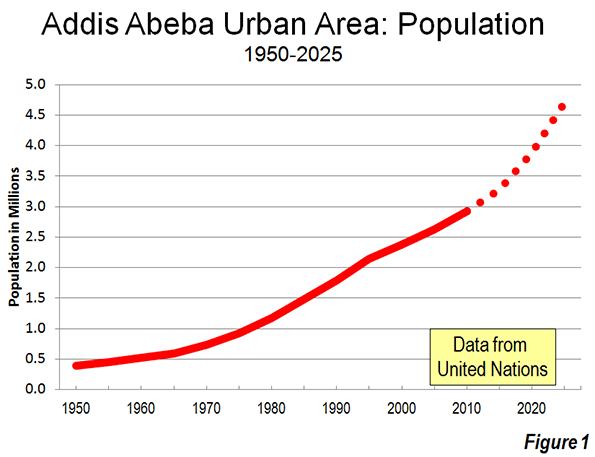

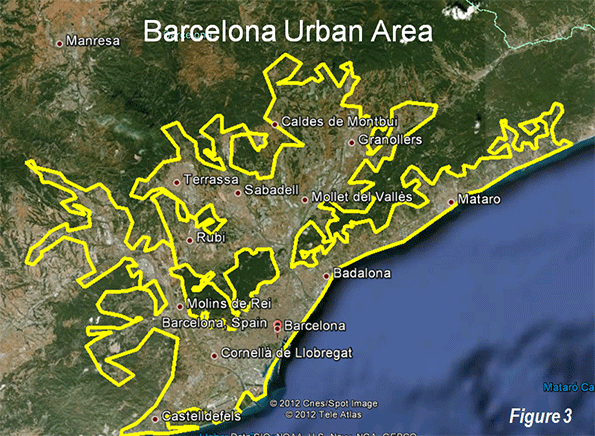

Within the last couple of years, the population of the world has become more than one half urban for the first time in history. By 2025, the world’s urban areas are expected to account for 58% of the world population, rising further to two-thirds in 2050. This represents a huge increase from the 29% that was urban in 1950, or estimates of approximately 10% (or less) in 1800. (Figure 1).

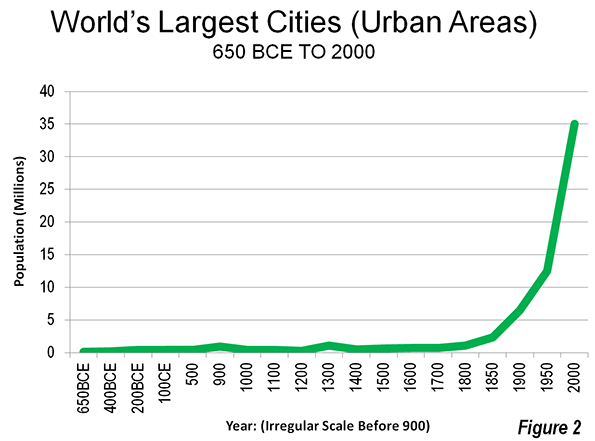

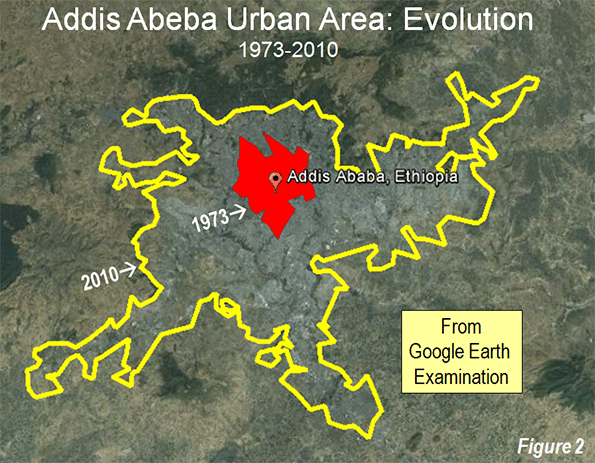

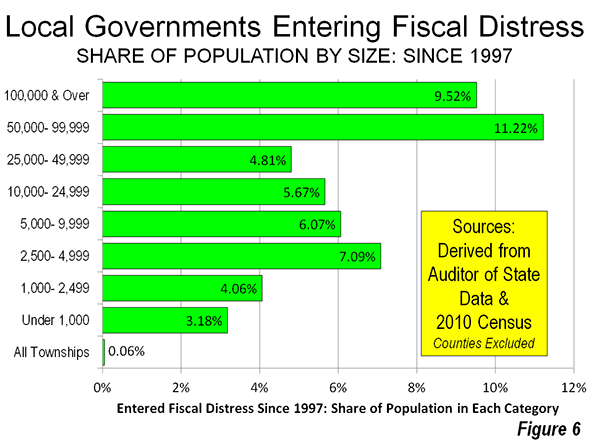

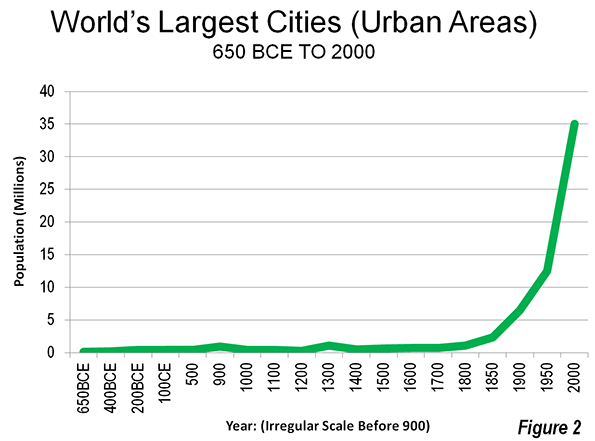

Urban areas have also gotten much bigger. In 1800, only Beijing had a population over 1,000,000. A number of others, such as Baghdad, Rome, Xi’an, Hanghzhou and Ayutthaya (Thailand) are reported to have reached between 1.0 and 1.5 million in the more distant past, but all had fallen back below the 1.0 million threshold by 1800 (Note 1). These population declines occurred for a variety of reasons, such as military losses, disease, as well as political and economic instability. In short, before the 19th century, large urban populations were largely unsustainable (Figure 2).

Over the intervening two centuries there has been an exponential increase in the number of large urban areas. By 1900, there were at least 15 urban areas over 1,000,000 population. By 2010, the figure had grown to approximately 450. New York had become the world’s first megacity (over 10 million population) by 1950, now there are at least 25 over 10 million.

What is Urban?

However, it would be a mistake to imagine that "half urban" means a world of large cities, or that the world is highly urbanized. The principal source for urban population data is the United Nations, which relies upon individual countries to provide the urban versus rural data. These nations each have their own definitions, which can vary markedly.

For example, in the United States, a settlement must reach 2,500 population before it is considered urban. Thus, Van, Texas, with a population of 2,502 in the 2010 census is urban, like New York with its 18 million. Canada requires settlements to have 1,000 residents. This means that Nobleford, Alberta, with a population of 1,000 in the 2011 census is urban, along with Toronto with its 6 million population. It seems curious that, with their similarities, United States and Canada have such different urban definitions.

However, as the UN indicates, differing definitions make sense in some cases. For example, agricultural villages in China can be larger than small urban areas in the United States, Canada or Western Europe. However, given the common view that agricultural dependence is an important difference between rural and urban, a Western urban definition would be inappropriate in China.

The differences in urban definitions can be substantial. According to the UN, urban definitions can require a population of as much as 50,000, and as little as 200, as in Sweden. With thresholds so low as 200, 1,000 or 2,500 population, the world urbanization data includes not only "cities," but also smaller settlements like small towns and villages (though there is no standard definition to differentiate between cities, towns and villages and the definitional problem is made worse by the sometimes use of these terms for administrative boundaries).

It is generally recognized that the world’s largest urban area is Tokyo, with a population of more than 35 million. However, there is no consensus about the smallest urban area in the world. Our candidate is Godegård, located in the Motala municipality (Östergötland County) in Sweden. The 2010 census indicated that Godegård had a population of 200 residents, at the urban definition threshold for Sweden. Godegårdians live in an urban area of 0.10 square miles or 0.26 square kilometers (see Google Earth image above).

Distribution of the World Urban Population

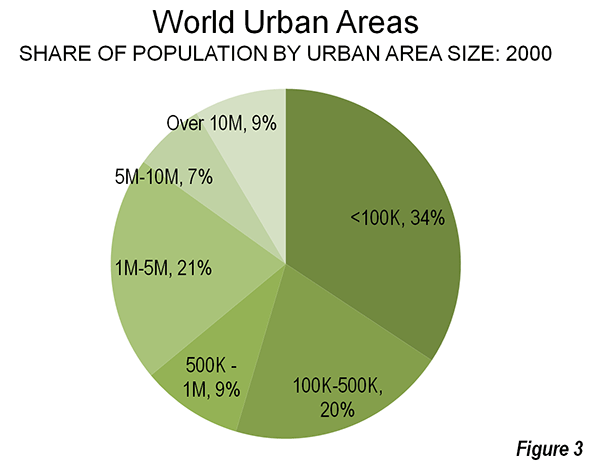

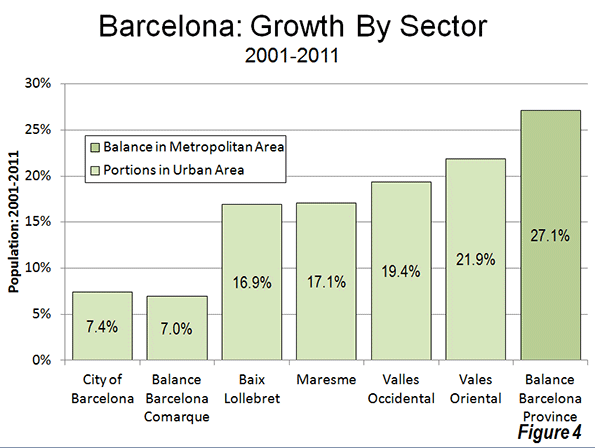

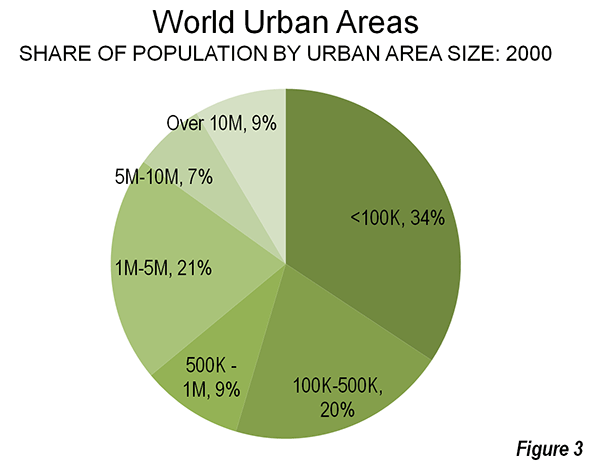

Urban areas are becoming physically larger and that a larger share of the urbanization is moving to the larger urban areas (areas of continuous urban development, including both urban cores and surrounding areas, generally called suburbs). However, a majority of the world’s urban population lives in smaller urban areas. In 2000, 30% of the world urban population lived in urban areas of less than 100,000 population (Note 2). Another 20% of the population lived in urban areas with between 100,000 and 500,000 population. Thus, nearly 55% of the world’s urban population lived in small and medium-sized urban areas in 2000 (Figure 3).

Historical and Projected Distribution of World Urban Population

The United Nations data is available back to 1950 and includes projections to 2025, based upon the size of urban areas in each year in five-year increments. The data is specific to the population categories, so that as an urban area changes categories (generally moving to a higher category), its population is reflected in the higher category and subtracted from the lower category.

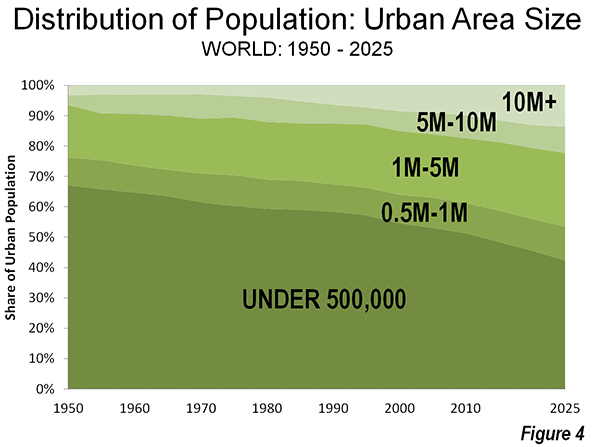

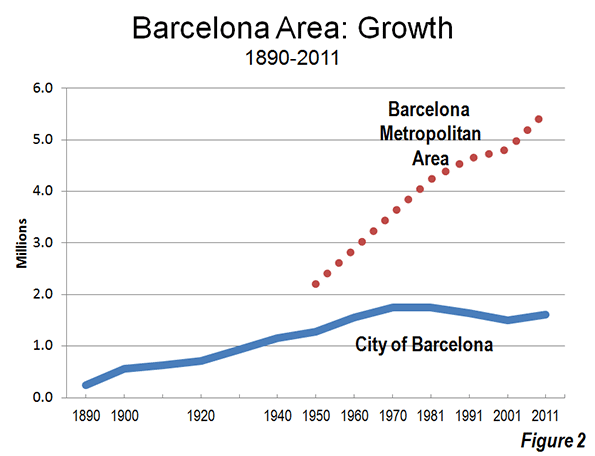

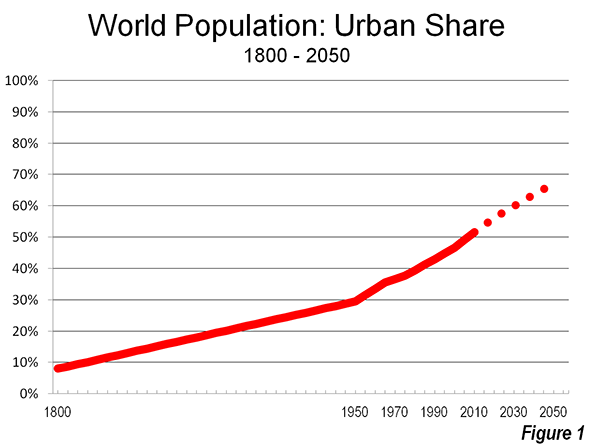

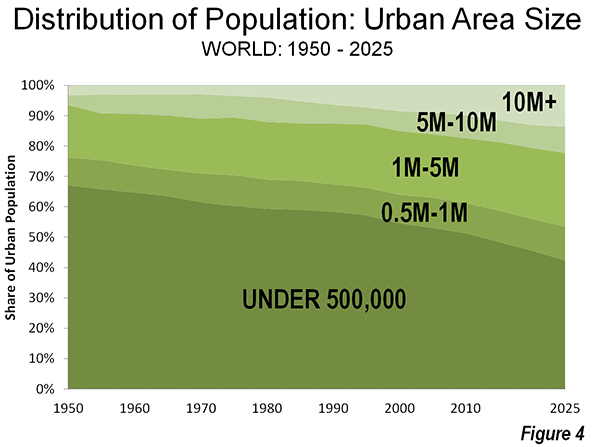

Despite all of the attention given to the world’s megacities, only 10% of the world’s urban residents are in urban areas with more than 10 million population. However, both the number and share of people living in megacities has increased substantially. From 1950 to 2010, the share of world urban population living in megacities more than tripled, from 3% to 10%. By 2025, the United Nations projects that the megacities will have nearly 14% of the urban population.

Strong growth has also emerged among the urban areas with from 5,000,000 to 10,000,000 population. Their share of the population has more than doubled since 1950 and is expected to rise further by 2025.

The share of the population in urban areas with from 1,000,000 to 5,000,000 population has grown more slowly, but accounted for 20% of world urbanization in 2010 and is expected to rise to nearly 25% by 2025. These urban areas are projected to add more people than the world’s megacities by 2025.

Urban areas from 500,000 to 1,000,000 population have increased their share even less, rising from 9% of the world urban population in 1950, to 10% in 2010 and a projected 11% by 2025.

Virtually all of the loss in urban population share has been in the urban areas with populations below 500,000. In 1950, these urban areas represented more than two thirds of the world urban population. This has since fallen to one-half and is expected to drop to 42% by 2025. (Figure 4)

Share of Growth

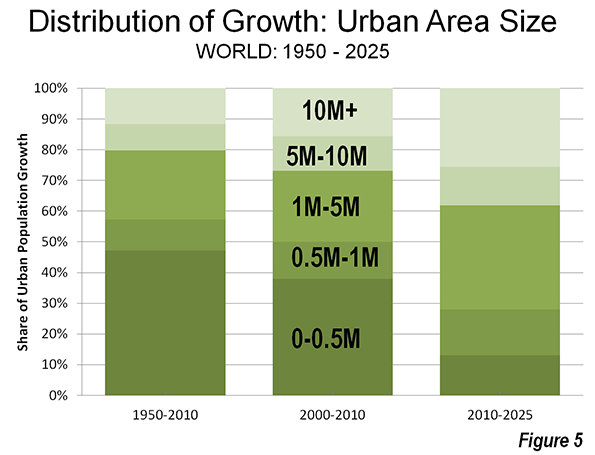

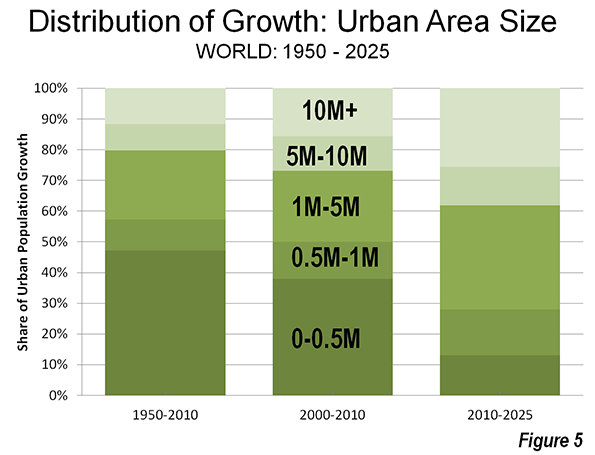

This does not mean the smaller urban areas are losing population. Between 1950 and 2010, these urban areas added more than 1.3 billion residents, and are expected to add nearly 150 million more between 2010 and 2025. However, urban population growth has been increasingly to the larger urban areas. Between 1950 and 2010, 47% of the urban population growth was in areas with less than 500,000 people. This dominance continued from 2000 and 2010, with a 38% share of the growth. However, it is expected that between 2010 and 2025 the greatest growth will be among urban areas with from 1,000,000 to 10,000,000 population (47%) and in the megacities (26%), while the smaller urban areas are expected to account for less than 13% of growth (Figure 5). Even so, the smaller urban areas will still have nearly three times as many residents as the megacities.

An Urbanizing, But Not Heavily Urbanized World

A half urban world is a world of settlements that includes villages, small towns, larger urban areas and megacities. Even as the population becomes more concentrated in the larger urban areas, smaller urban areas will continue to account for a large share of the world urban population for the foreseeable future. Thus, a half (or more) urban world will continue to include the likes of Godegård, Nobleford and Van as well as megacities that could approach 50 million.

Wendell Cox is a Visiting Professor, Conservatoire National des Arts et Metiers, Paris and the author of “War on the Dream: How Anti-Sprawl Policy Threatens the Quality of Life.”

—-

Photo: Google Earth image of Godegård, Sweden, which may be the smallest urban area in the world (see text above).

Note 1: There is a considerable range of research on the size of the largest urban areas throughout history. The authoritative source is Tertius Chandler (Four Thousand Years of Urban Growth: An Historical Census).

Note 2: This estimate is developed from data in Angel, Parent, Civco, Blei and Potere (2010) and United Nations data. Angel, et al (also see A Planet of People: Angel’s "Planet of Cities") provide estimates for urban areas from 100,000 to 500,000 population in 2000, which makes it possible to estimate the population of urban areas below 100,000 population, using UN data for 2000. Estimates for urban areas under 100,000 population is not available for other years.