Istanbul is unique in straddling two continents. The historical city was concentrated on the European side of the Bosporus, the wide, more than 20 mile long strait linking the Sea of Marmara (Mediterranean Sea) in the south to the Black Sea in the north. Nearly all of the historic city was located on a peninsula to the south of the Golden Horn, an inlet off the Bosporus. By 1990, the urban area had expanded to occupy large areas on both sides of the Bosporus.

The Urban Area

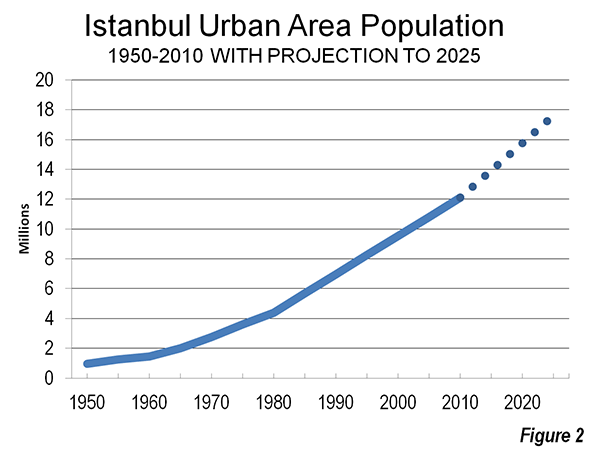

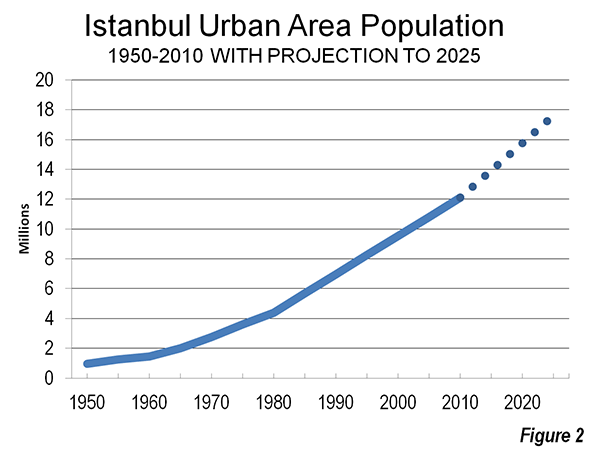

Istanbul, like many other developing world urban areas, has grown rapidly since World War II. In 1950, the urban area contained a population of less than 1,000,000. That is similar to the present population of urban areas like Edmonton, Adelaide and Raleigh. By 2012, the urban area had a population of nearly 12.7 million.

Few of the world’s cities boast a more storied history than Istanbul. It started as the Greek colony of "Byzantium," in the 7th century, BCE. By the fourth century, CE, Byzantium , taking advantage of Rome’s decline, was designated capital of the Roman Empire by the Emperor Constantine. The city was subsequently renamed "Constantinople." The final name change, to "Istanbul," was finalized in the early years of the post-Ottoman Empire Republic in the 1920s.

Constantinople became capital of the Eastern empire. Constantinople eventually emerged as the seat of Eastern Christianity (Easter Orthodoxy) and remains so today, despite more than 500 years of Islamic predominance under the Ottomans and later, the Republic of Turkey.

Like many ancient cities, Constantinople experienced wide swings in population, reaching 400,000 in 500 C.E. then dropping to under 50,000 by the time of the Ottoman conquest (1453). But the conquest proved a boon to the city.

By 1550, the population had risen to 660,000. At the time only Beijing was larger (690,000). At that point, the city walls (the present district municipality of Fatih) and urbanization north of the Golden Horn amounted to an estimated six square miles (15 square kilometers), for a population density of approximately 110,000 per square mile (42,500 per square kilometer). Such hyper-densities were typical of pre-1800 cities, when walking was the predominant mode of transport. Some older cities were even more dense: 17th century, Paris approached 175,000 per square mile (67,000 per square kilometer (Note: Walking Cities)

Caption: Sultan Ahmed Mosque (Blue Mosque), 17th Century, CE

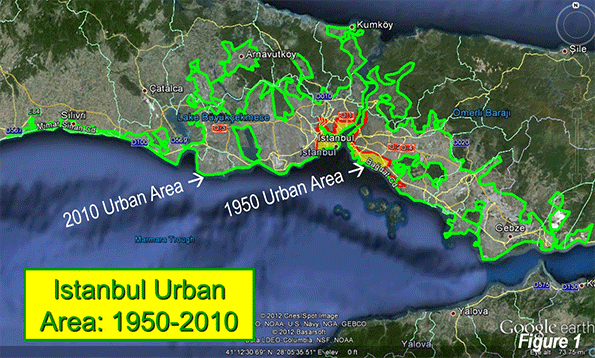

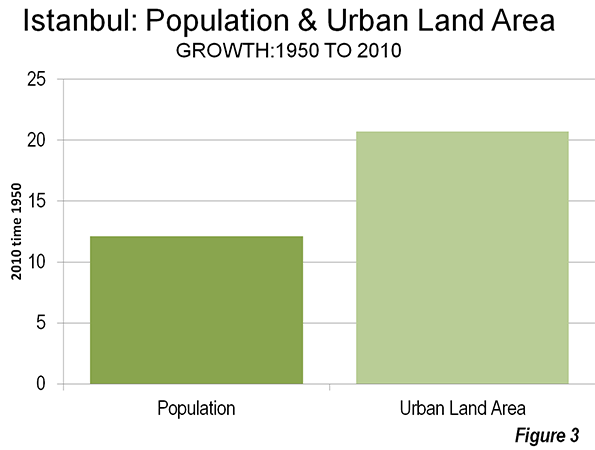

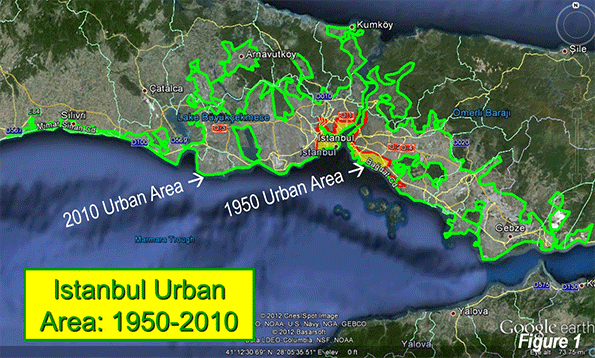

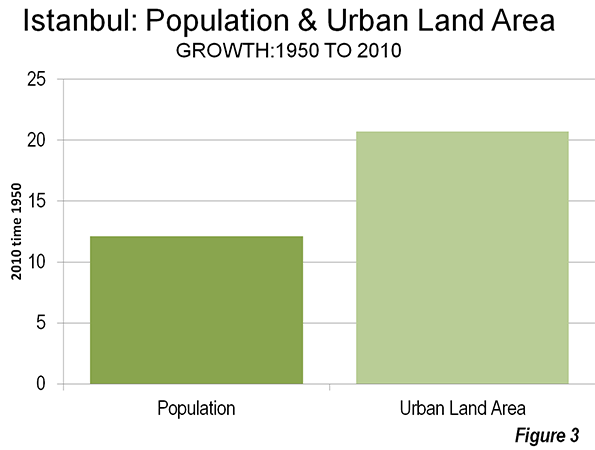

In the ensuing centuries, the urban area grew modestly to less than 1,000,000 in 1950, when the urban population density fell to 40,400 per square mile (15,600 per square kilometer). Rapid growth was to follow to today’s more than 12 million, along with a further drop in urban density, to 24,300 per square mile or 9,400 per square kilometer (Note: The Density of Istanbul). The physical expansion of the urban area now stretches north all the way to the Black Sea (Figure 1 shows the present extent of the urban area and the 1950 urban area). Over the 60 years, the urban area population grew more than 12 times, but the urban land area grew nearly 21 times (Table 1). Istanbul demonstrates the near universal truth that as cities grow, they become less dense (Figure 2).

| Table 1 |

|

|

|

|

|

| Istanbul Urban Area: Population & Density from 1550 |

|

|

| Year |

Population in Millions |

Land Area: Square Miles |

Land Area: Square Kilometers |

Density:Square Mile |

Density: Square Kilometer |

| 1550 |

0.66 |

6 |

16 |

110,000 |

42,500 |

| 1950 |

0.97 |

24 |

62 |

40,400 |

15,600 |

| 2012 |

12.66 |

520 |

1,347 |

24,300 |

9,400 |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

| Change: 1550-1950 |

47% |

288% |

|

-63% |

|

| Change: 1950-2010 |

1205% |

2073% |

|

-40% |

|

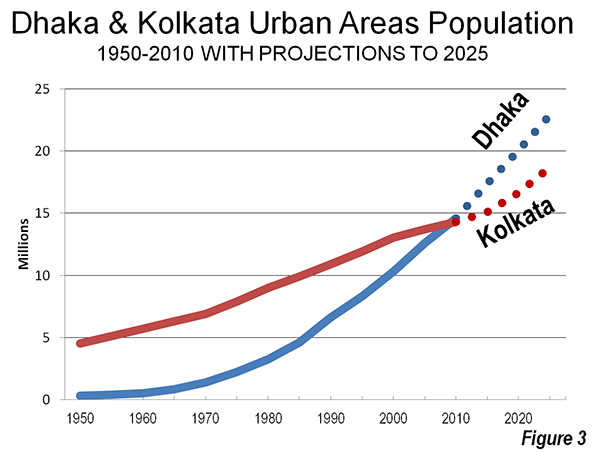

At United Nations projected growth rates, the urban area should approach 18 million by 2025 (Figure 2). There are reports of increased migration to Istanbul from Asian Turkey, which if continued, could make the 2025 figure even higher.

The Metropolitan Metropolis and Province

Istanbul is a both a metropolitan municipality and a province and can be considered a metropolitan area (labor market area). The province, most of it rural, covers land area of more than 2,100 square miles (5,300 square kilometers) and had a population of approximately 13.5 million according to the 2011 census. The urban area (area of continuous urban development) is much smaller, at only 520 square miles (1,347 square kilometers). Nearly all the population is concentrated in the urban area.

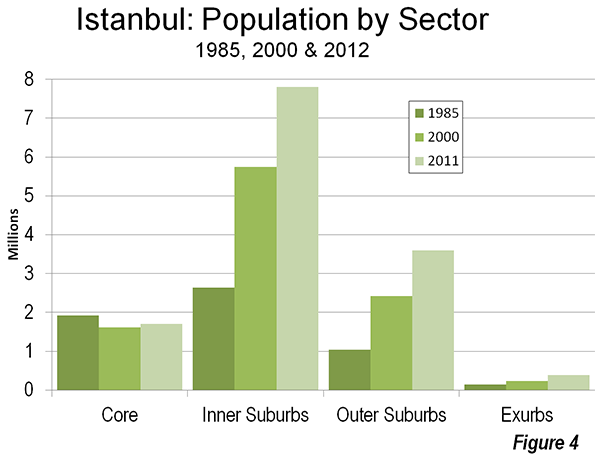

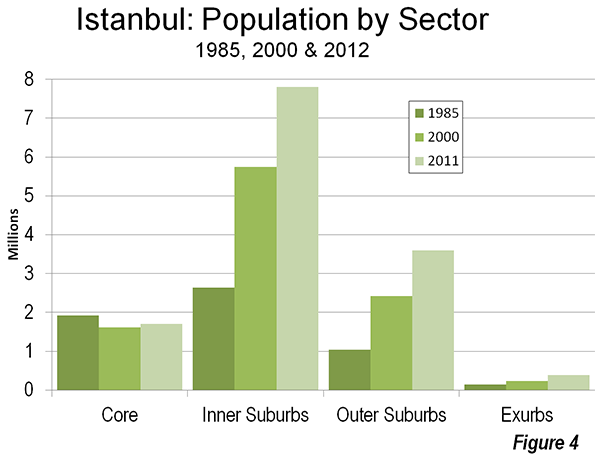

Since 1985, the metropolitan area’s growth largely has been outside the core. The historic core, on the peninsula (Fatih), lost 27 percent of its population, while the balance of the core, district municipalities to the north of the Golden Horn and to the west, lost 5 percent. Such core area losses have frequently occurred in many major metropolitan areas (for example, Osaka, Seoul, Mumbai, Chicago, Milan, Buenos Aires, and Mexico City).

The inner ring, including district municipalities further to the west and north of the core on the European side and municipalities on the Asian side have captured nearly all the growth. From 1985 to 2011, inner ring district municipalities added 5,000,000 residents. The outer ring of suburban district municipalities gained 2.5 million residents with the greatest percentage growth, at nearly 250 percent. There has also been growth in exurban district municipalities (beyond the urban area), though it has been much more modest (Figure 4 and Table 2).

| Table 2 |

|

|

|

|

|

| Istanbul: Population Growth by Sector: 1985-2012 |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

1985 |

2000 |

2011 |

Change: 1985-2011 |

| Historic Core: Fatih |

591 |

459 |

429 |

-27% |

| Balance of Core |

1,336 |

2,175 |

1,270 |

-5% |

| Inner Ring |

2,635 |

5,747 |

7,800 |

196% |

| Outer Ring |

1,044 |

2,424 |

3,598 |

245% |

| Exurbs |

|

147 |

240 |

386 |

162% |

| Total |

|

5,753 |

11,045 |

13,483 |

134% |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

| Population in 000s |

|

|

|

|

Ascendant Asia

While European Istanbul has been dominant for millennia, it is perhaps fitting that Asian Istanbul is on the rise, with nearly 40 percent of the population, up from 31 percent in 1985. Asian Istanbul was made substantially more accessible by the first bridge over the Bosporus (1973).

Linking Istanbul

Istanbul is served by two major east-west freeways. Each (the O-1 and O-2) both have their own crossings of the Bosporus. Other freeways feed these both in Europe and Asia. The development of the mass transit system is somewhat curious. The inner Fatih area and Beyoğlu contain the historically most important commercial centers. However, they are being fast replaced by new skyscraper developments in Levent and Maslak. This is similar to the emergence of newer commercial cores that have become more important the older cores, such as in Mexico City, Sao Paulo, Beijing, and Manila, where multiple, large cores have grown.

Yet, Istanbul’s urban rail system keys on the old commercial centers. Both Levent and Maslak are located on a single Metro line, which makes them less convenient than if radial lines were being built to these centers instead. Both centers have good road access. Levent is located between the O-1 and the O-2 motorways, while Maslak is located just north of the O-2.

A passenger rail tunnel between Asia and Europe, the first, is scheduled for opening to Fatih in 2015. Local authorities predict that this and other pending projects could increase the share of trips by rail in Istanbul from 3.6 percent to as much as 27.6 percent. No such market share increase has ever occurred in the world since automobiles have become widely available. Further, like Istanbul’s transit system in general, the project will not provide direct service to Levent or Maslak.

Becoming Europe’s Largest Urban Area

Istanbul has always been considered European and remains so even with its huge suburbs in Asia. Istanbul trails Moscow as Europe’s largest urban area, but by 2025 should be the largest. Indeed, it seems likely that Istanbul will be the only European urban area to reach a population of 20 million, as much of Europe faces stagnant or even declining population.

Wendell Cox is a Visiting Professor, Conservatoire National des Arts et Metiers, Paris and the author of “War on the Dream: How Anti-Sprawl Policy Threatens the Quality of Life.”

——————–

Note: Walking Cities: Walking constrained the physical expansion of cities, and thus the population. As result, few pre-1800 cities reached 1,000,000 population and most were not able to sustain that level. The great expansion of urban areas followed, as walking was replaced by the more efficient transport modes of transit and automobiles, both of which permitted a sizeable expansion of urban footprints and labor markets. The subsequent economic growth is legendary and accounts for having attracted so many people from the countryside. In 1800, estimates suggest that urban areas contained under 10 percent of the world population. Today, the figure is 52 percent, according to the United Nations. This includes all urbanization, from the largest cities to the smallest towns.

Note: The Density of Istanbul. The province, most of it rural, covers land area of more than 2,100 square miles (5,300 square kilometers) and had a population of approximately 13.5 million according to the 2011 census. The urban area (area of continuous urban development) is much smaller, at only 520 square miles (1,347 square kilometers). This article highlights the urban density of Istanbul, which is the population per square mile or square kilometer. Other sources cite much lower figures, for the province/metropolitan municipality (metropolitan area). However, metropolitan area densities are not urban area densities. Metropolitan areas virtually always have more rural land than urban land, so their population cannot be included in calculations of urban density. The population and density noted above is based upon the 2011 census and will be reflected in the next edition of Demographia World Urban Areas.

Photo: Hagia Sophia (Santa Sophia) Church (now museum) built by Justinian (6th Century CE). Photos by author.

There is the understandable concern that eventually, the promoters will approach the state or the federal government for support. Not so, say Texas Central High Speed Railway officials. According to President Robert Eckels, not only is there no plan for subsidies, but "investors would likely walk away from a project that couldn’t stand on its own."

There is the understandable concern that eventually, the promoters will approach the state or the federal government for support. Not so, say Texas Central High Speed Railway officials. According to President Robert Eckels, not only is there no plan for subsidies, but "investors would likely walk away from a project that couldn’t stand on its own."