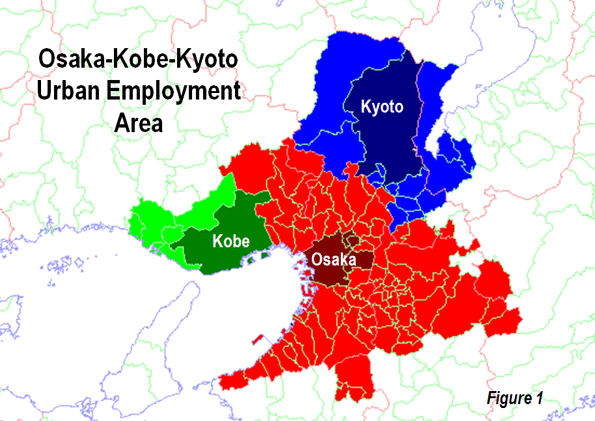

Osaka-Kobe-Kyoto is Japan’s second largest urban area and ranks as the 12th largest urban area in the world. With a population of approximately 17,000,000 and a land area of 1240 square miles (3200 square kilometers), Osaka-Kobe-Kyoto has a population density of 13,700 per square mile (5,200 per square kilometer), making it the most dense major urban area in Japan and among the denser urban areas in the high income world. The larger metropolitan region includes four prefectures, Osaka, Kyoto, Kyoto and Nara (Figure 1).

Adapted from WikiCommons user Kzaral

World’s Largest Conurbation

Osaka-Kobe-Kyoto is a conurbation, an urban area that has grown together from multiple cores (here, the urban areas of Osaka, Kobe and Kyoto). Most urban areas grow concentrically from a single core. In the process their suburban growth can engulf and incorporate smaller urban areas (such as Gifu in Nagoya, Bogor in Jakarta or Newark in New York), However, conurbations — such as Rhine-Ruhr region in Germany (Essen, Dortmund, Duisburg, and Bochum), Katowice-Gliwice-Tychy (upper Silesia) in Poland, Dallas-Fort Worth and Minneapolis-St. Paul in the United States — develop when major urban areas grow together (or merge), forming a larger urban area.

The municipality of Osaka, the largest in the region, long had been Japan’s second municipality exceeded by Yokohama (in the Tokyo region) in 1980; in the 17th century it was the country’s commercial capital. Kobe, across Osaka Bay (20 miles or 32 kilometers), was one of the most cosmopolitan cities and was the site of the devastating 1995 earthquake, from which it has recovered remarkably. Kyoto is the former, historic, imperial capital as is 35 miles (55 kilometers) north of Osaka. The previous imperial capital, the historic municipality of Nara is also located in the region. Both cities are well known for its historic temples.

Post-War Growth

Between 1950 and 1970, the Osaka-Kobe-Kyoto region experienced extraordinary growth, adding nearly 5.7 million residents. The increase from 9.8 million to 15.5 million exceed that of all urban areas in the world except Mexico City (approximately 6 million) and Tokyo (11 million). Tokyo’s 20 year increase was the largest numerically in history for a metropolitan region. By comparison, Los Angeles, the Western world’s fastest growing metropolitan region between 1950 and 1970, added 5.0 million new residents. In 1970, only the Tokyo and New York urban areas were larger than Osaka-Kobe-Kyoto.

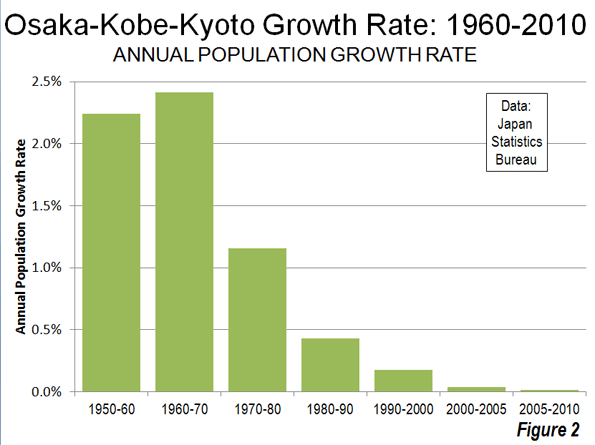

The region grew quickly after the Second World War but experienced an even higher growth rate — well in excess of two percent during Japan’s great economic takeoff in the 1960s. During the 1970s, the annual growth rate dropped to 1.5%, still well above the current experience of most high income urban areas.

Stagnating Growth, Presaging Decline

As it turned out, the 1970s represented the conclusion of Osaka’s strong growth. From then on, growth fell quickly and has since virtually stopped. It appears likely that Osaka-Kobe-Kyoto will become the world’s first megacity (over 10 million population) to fall into population decline (see end note).

According to the 2010 census, the metropolitan region’s population of approximately 18,500,000 barely grew, adding only 13,000 residents from 2005. This represents an annual growth rate of 0.014%, a decline of 60% from its anemic 0.036% growth rate between 2000 and 2005 (Figure 2).

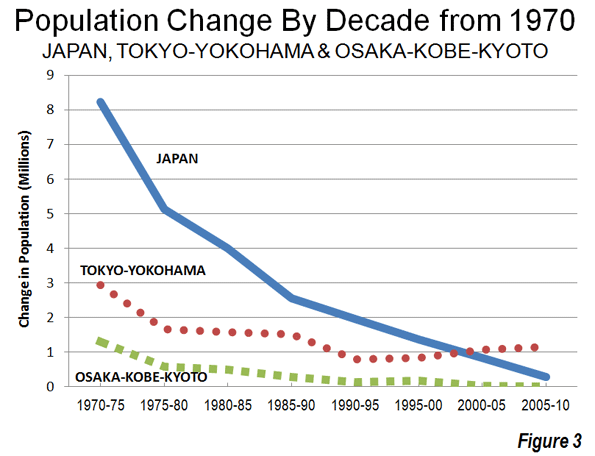

Osaka-Kobe-Kyoto’s is falling behind even Japan’s slow growth pace, being 2005 to 2010 expanding by less than one third of the national rate. One reason for this lies in continued concentration in the Tokyo metropolitan region (Figure 3). The Tokyo area captured 56% of the growth between 1970 and at 2010. Over the past five years Tokyo has added 1.1 million people, while the balance of the nation lost 1.4 million people. Japan’s population has stabilized and is expected to fall into decline in the years to come.

Suburban Expansion

As is typical of major metropolitan regions in the world virtually all of the growth in Osaka-Kobe-Kyoto since 1950 has been outside the historically core municipalities. Only 150,000 of the 6,250,000 population increase from 1950 to 2010 was in the municipalities of Osaka, Kobe or Kyoto. The suburbs accounted for nearly 98% of the region’s growth.

As growth came to a virtual stop, however, the historical core municipalities have done better. Between 2000 and 2010, the municipalities of Osaka, Kobe and Kyoto had added 125,000 people, while suburban areas lost 79,000. The net result was a 46,000 population increase between 2000 and 2010 (Table).

| Osaka-Kobe-Kyoto Metropolitan Region | ||||||

| Population Trend: 1920-2010 | ||||||

| Historical Core Municipalities | ||||||

| Year | Osaka | Kobe | Kyoto | Total | Suburban | Region |

| 1920 | 1,253 | 609 | 591 | 2,453 | 4,289 | 6,742 |

| 1930 | 2,114 | 765 | 788 | 3,667 | 4,668 | 8,335 |

| 1940 | 3,252 | 1,090 | 967 | 5,309 | 5,056 | 10,365 |

| 1950 | 1,956 | 765 | 1,102 | 3,823 | 5,941 | 9,764 |

| 1960 | 3,012 | 1,114 | 1,285 | 5,411 | 6,774 | 12,185 |

| 1970 | 2,980 | 1,289 | 1,419 | 5,688 | 9,780 | 15,468 |

| 1980 | 2,648 | 1,367 | 1,473 | 5,488 | 11,866 | 17,354 |

| 1990 | 2,623 | 1,477 | 1,461 | 5,561 | 12,556 | 18,117 |

| 2000 | 2,599 | 1,494 | 1,468 | 5,560 | 12,883 | 18,443 |

| 2005 | 2,629 | 1,525 | 1,475 | 5,629 | 12,847 | 18,476 |

| 2010 | 2,666 | 1,545 | 1,474 | 5,685 | 12,804 | 18,489 |

| In 000s | ||||||

| Data from Census of Japan | ||||||

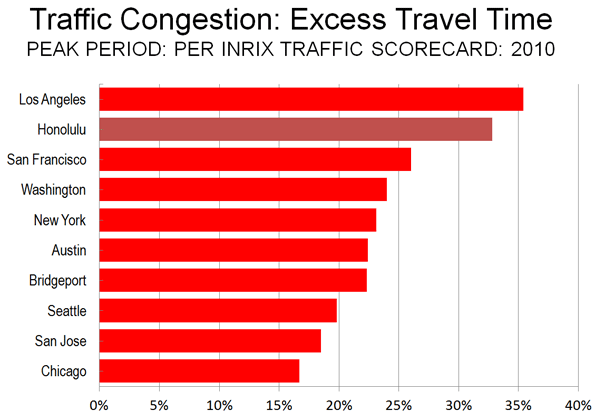

Transport in Osaka-Kobe-Kyoto

With its high density, Osaka-Kobe-Kyoto has a high level of traffic congestion. Osaka-Kobe-Kyoto ranks 19th highest road traffic density out of more than 90 urban areas for which data is available in the Millennium Cities database. This traffic density is despite the fact that Osaka-Kobe-Kyoto has the highest mass transit market share of any high-income world megacity outside Tokyo. In 2007, 57 percent of trips in the metropolitan region were by mass transit, compared to Tokyo’s 65 percent. By comparison, mass transit’s market share is approximately 30 percent in the Paris region and 10 percent in greater New York. The annual number of transit trips in Osaka-Kobe-Kyoto alone is more than one-half the total US ridership, despite having a population only 6% of the US.

However, lest any conclude that Osaka-Kobe-Kyoto (or Tokyo) might be a model for US or European metropolitan areas, it must be noted that transit’s market share has dropped from 80 percent in the late 1980s. Osaka-Kobe-Kyoto (as well as Tokyo and Nagoya) also demonstrate the "mass transit cannot be profitable" claim is a myth. In each of these three metropolitan areas, the vast majority of transit travel is on profitable private suburban railways.

Osaka-Kobe-Kyoto: The Future?

Very few large metropolitan areas have experienced population declines, and none with the vast scale and historic importance of Osaka-Kobe-Kyoto. Smaller metropolitan areas like Pittsburgh, Cleveland, Liverpool, Manchester and Genoa have stagnated and even experienced periods of population decline. But none have faced a future bleaker than likely for Osaka-Kobe-Kyoto. United Nations population projections indicate that Japan will decline in population by 20 percent between 2010 and 2050. As the nation’s economic activity continues to centralize in Tokyo, this could be particularly be ominous for Osaka-Kobe-Kyoto. The trains could get less crowded.

Wendell Cox is a Visiting Professor, Conservatoire National des Arts et Metiers, Paris and the author of “War on the Dream: How Anti-Sprawl Policy Threatens the Quality of Life”

—–

Note: New York is reputed to have become the first megacity in the world in the 1920s. As late as 1980, there were only five urban areas in the world with more than 10 million residents. In 2010 there were 25 megacities.

Photo: Himeji Castle, Kobe Prefecture. By Jean Love