In a just released poll by the Bay Area Council a majority of respondents indicated an expectation that traffic congestion in the Bay Area (the San Jose-San Francisco combined statistical area) is likely to get worse.

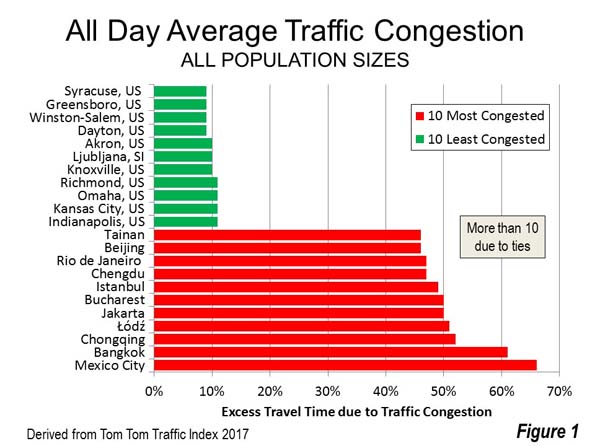

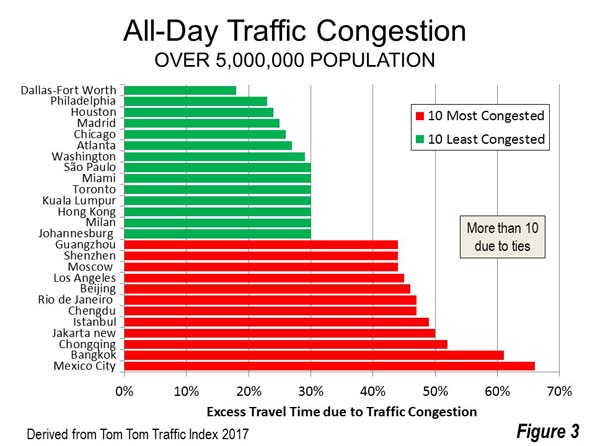

It is already bad enough. The Bay Area includes two major urban areas (over 1,000,000 population), with San Francisco ranked second worst in traffic congestion in the United States, closely following Los Angeles. In San Francisco, the average travel time during peak travel hours was reported to be 41 percent worse due to traffic congestion, according to the 2015 Annual Mobility Report from the Texas A&M Transportation Institute. That means a trip that would normally take 30 minutes without congestion stretches to 42 minutes. Los Angeles is only slightly worse, where the travel time congestion penalty is 43 percent. In the adjacent and smaller San Jose urban area, congestion adds 38 percent to travel times, tying with Seattle as third worst in the nation.

According to a Mercury News article by George Avalos, “The Bay Area’s traffic woes are so severe that more than two-thirds of the region’s residents surveyed in a new poll are demanding a major investment to fix the mess — even if that means stomaching higher taxes.” Residents perceive the problem as an “emergency that requires drastic solutions,” and 70 percent of those asked support a “major regional investment” to improve traffic.

Those who expect traffic congestion to get worse are probably right. Public policies in California and the Bay Area virtually require it. For example, the state has proposed a “road diet” program that would place significant barriers in the way of highway capacity expansion. Without capacity expansion, traffic is likely to only get worse.

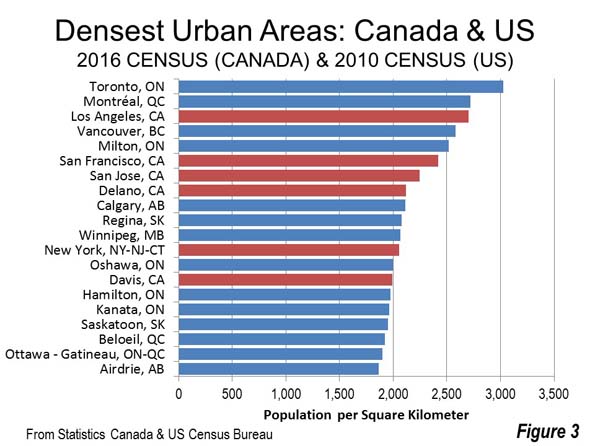

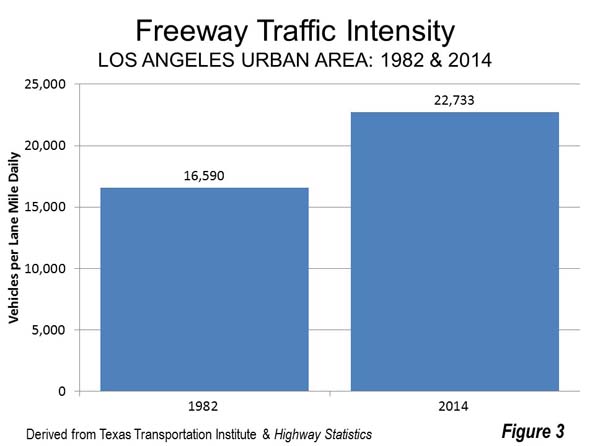

The regional transportation plan (Plan Bay Area), adopted by the Association of Bay Area Governments and the Metropolitan Transportation Commission, seeks significant densification (called “pack and stack” by critics). Should the plan succeed, you can bank on traffic congestion getting even worse. It is no coincidence that Los Angeles, San Francisco and San Jose have the worst traffic congestion in the nation. They are also the nation’s three densest urban areas. Indeed, higher densities are associated with greater traffic congestion.

There are, of course, things that can be done. But no one in the Bay Area should suspect that California, with its present policies, is up to the job.

Take, for example, the newly announced plan by Governor Brown and legislative leaders to spend $52 billion over the next 10 years on transportation, much of it on roads. The program would require the largest increase in the state’s gasoline tax and vehicle fees in history. It will all go to repairs and maintenance, which are necessary, and to transit, walking and bike infrastructure. Yet, according to press reports, it contains nothing for the highway capacity expansions required for serious congestion relief.

It is a sad commentary that the state has been deferring maintenance on the roads that carry more than 98 percent of the state’s surface (non-airline) travel, while continuing to pursue a mixed conventional-high- speed rail proposal that, at the moment, is set to cost $64 billion. If ever finished, it will probably cost much more and will be lucky to carry even one percent of California travel (See note).

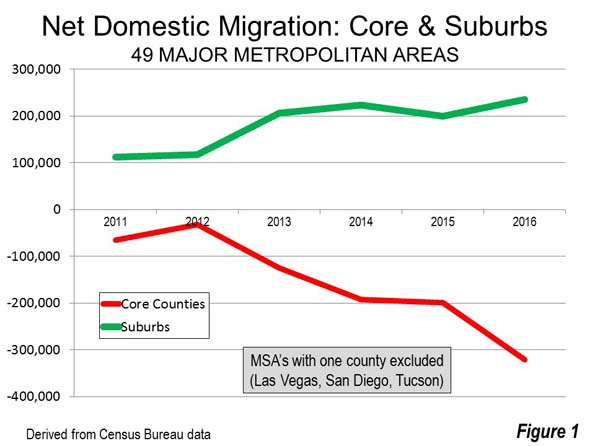

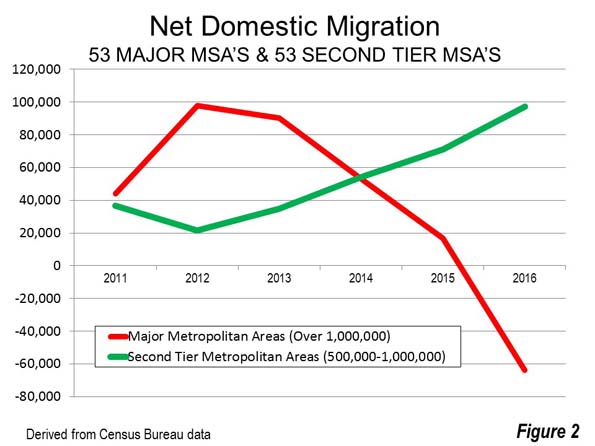

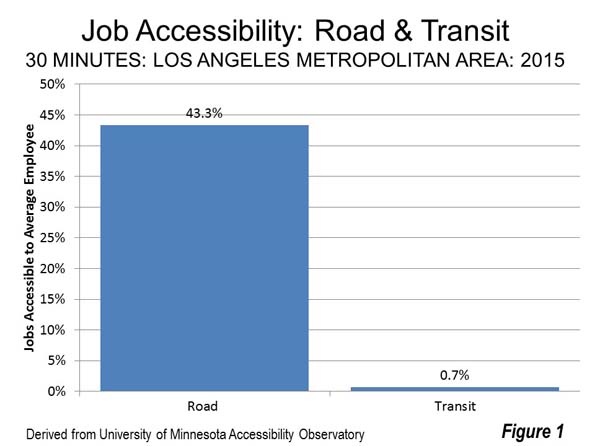

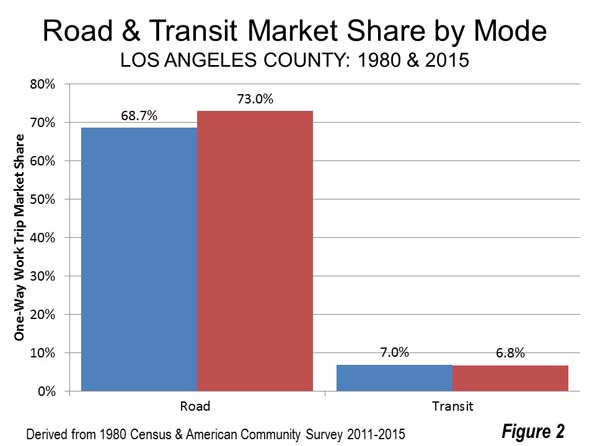

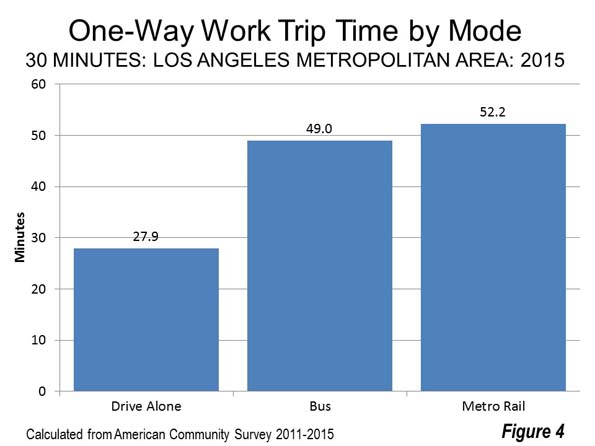

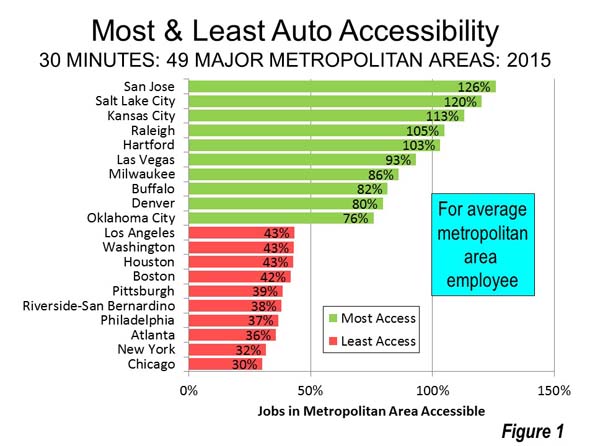

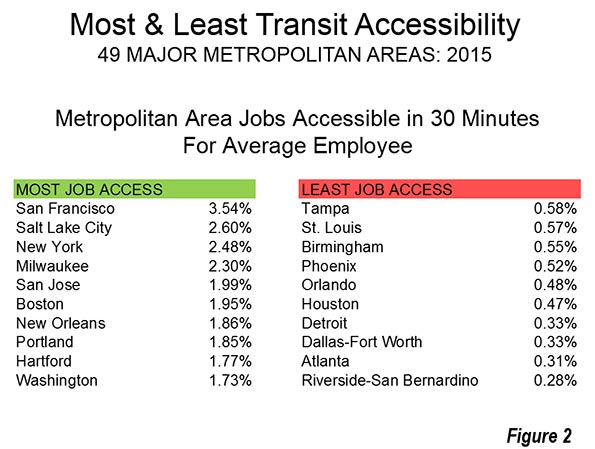

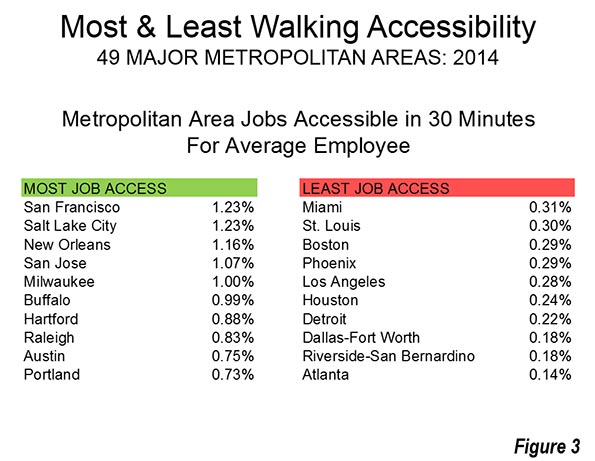

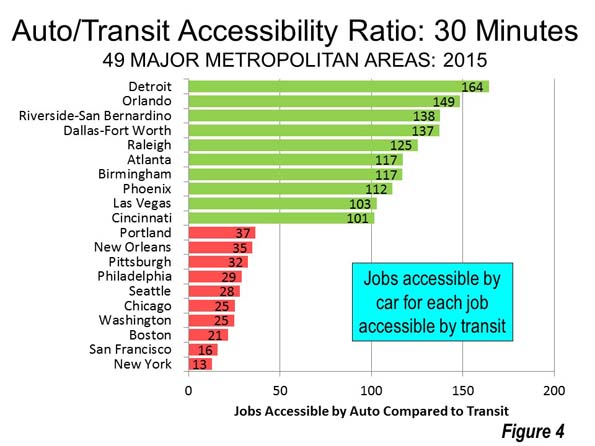

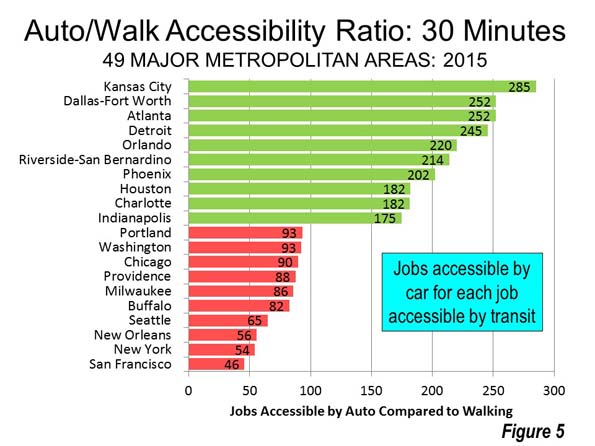

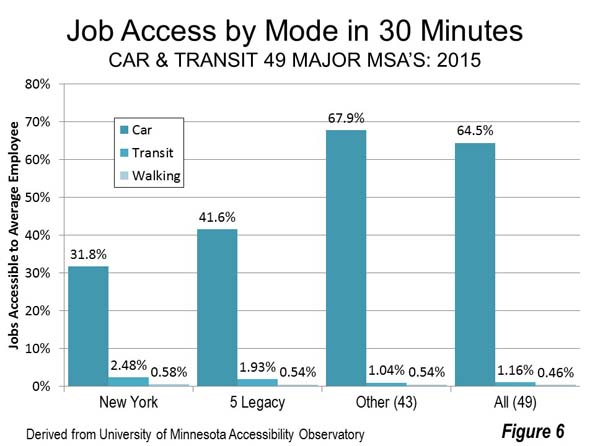

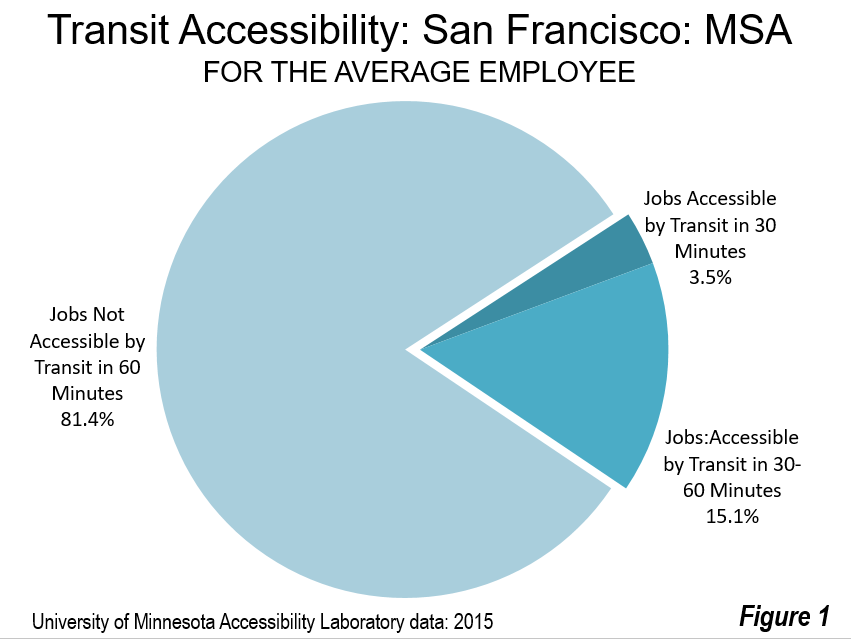

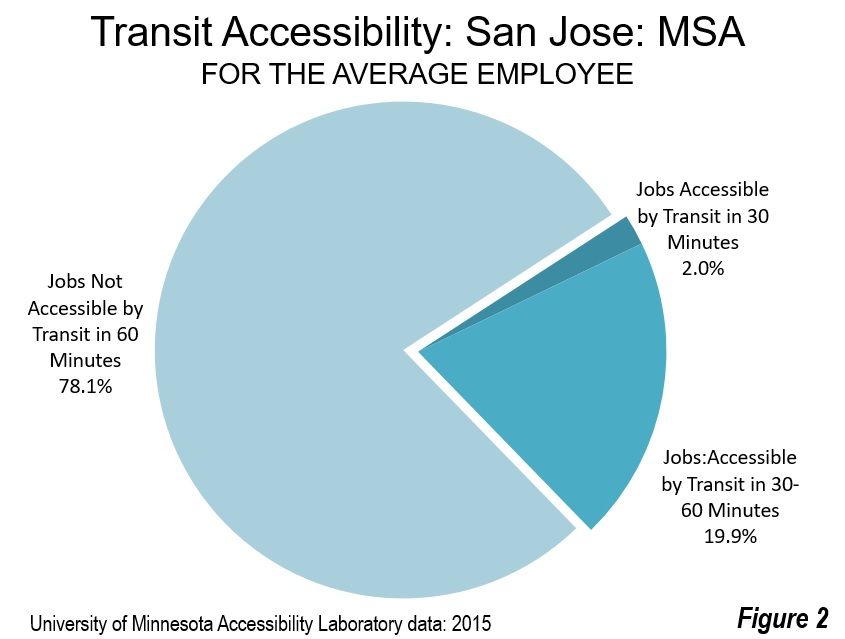

Some may romantically anticipate that transit can substitute for the automobile and reduce traffic congestion. This is fantasy, as the US experience with urban rail proves. For the most part, transit cannot get you from here to there in the modern metropolitan area. In the Bay Area, the average commuter using transit can reach only 3.5 percent of the jobs in 30 minutes in the San Francisco metropolitan area and 2.0 percent of the jobs in the San Jose metropolitan area (according to the University of Minnesota Accessibility Laboratory). Even with a 60-minute commute, the share of jobs accessible in both areas is only about 20 percent. Even where transit is most intense in the San Francisco Bay Area, the average commuter can reach 16 times as many jobs in 30 minutes and eight times as many in 60 minutes (Figures 1 and 2). That is not to minimize the value of transit, which carries 50 percent of commuters to the nation’s six largest downtown areas (New York, Chicago, Philadelphia, San Francisco, Boston and Washington). But in each of these metropolitan areas the overwhelming percentage of jobs are outside downtowns, where the overwhelming share of commuting is by car.

The hope of some planners that traffic will get so bad people will switch to transit requires service that takes people where they want to go. They must still be wondering why people persist in driving their cars that take them where they need to go instead of switching to transit that takes them where planners would like them to go. Of course, the reality is that transit provides little mobility beyond the urban core and cannot be made to do so at any reasonable cost.

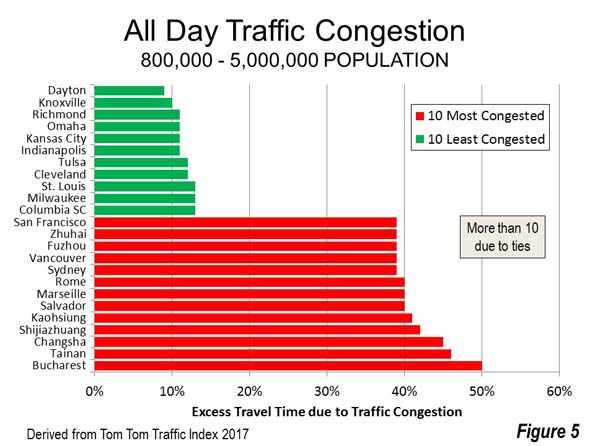

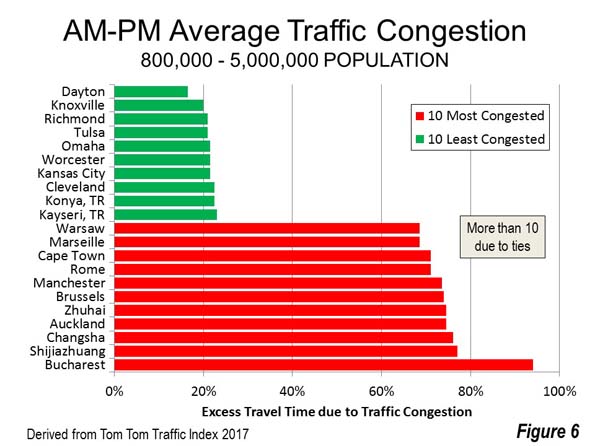

The bottom line is that traffic congestion can get considerably worse. In Bangkok and Mexico City, traffic congestion is at least 70 percent worse than in the Bay Area, according to the Tom Tom Traffic Index. This is despite much lower automobile ownership rates.

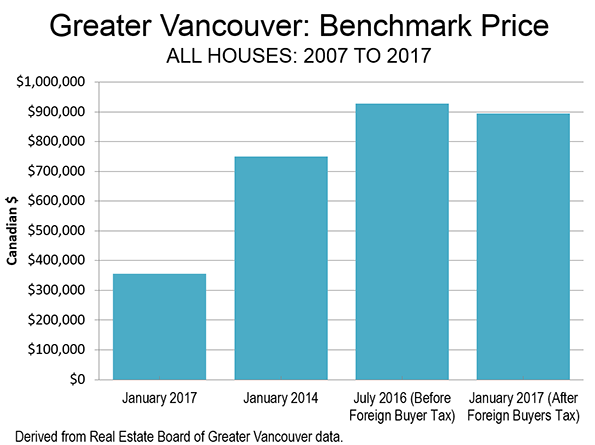

The survey indicated another alternative for those who really cannot stand the Bay Area’s unbearable and worsening traffic congestion. Move. The Bay Area Council found that 40 percent of respondents and 46 percent of Millennials are considering moving from the area in the next few years.

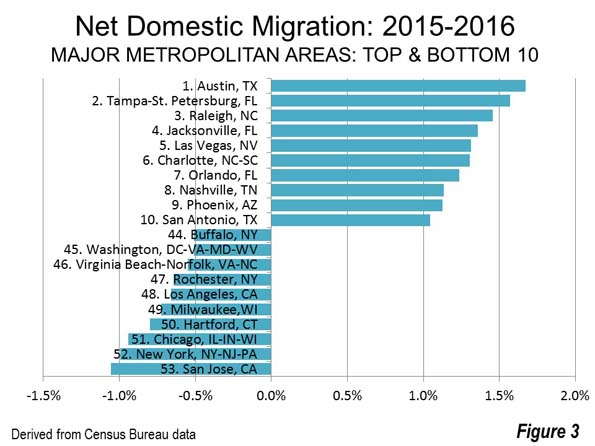

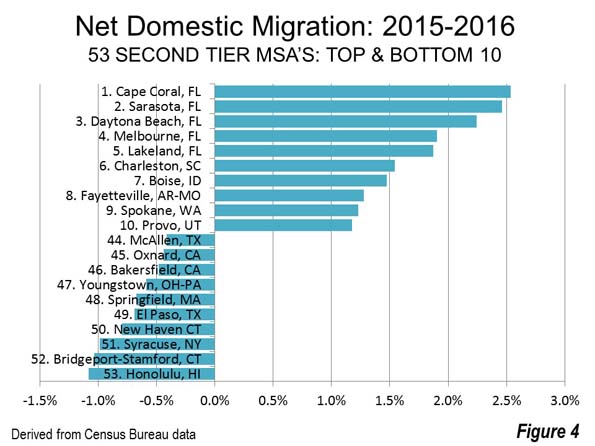

Indeed, that is beginning to happen. After a five-year respite in the Bay Area’s substantial net domestic out-migration, 26,000 more people left than arrived in 2016. The big loser was Santa Clara County (a net loss of 21,000), while San Francisco County (city) lost 7,000. Between 2000 and 2009, the Bay Area had lost more than 500,000 net domestic migrants.

For the millions who will remain in the Bay Area, however, moving is not a solution. Of course, a dawn of reason could occur among the leadership of California and the Bay Area, in which ideologically preferred solutions are replaced by practical strategies that work. Things will probably have to get much worse for the public to demand that.

Note: See my co-authored reports with Joseph Vranich, The California High Speed Rail Proposal: A Due Diligence Report (2008), and California High Speed Rail: An Updated Due Diligence Report (2012).

Wendell Cox is principal of Demographia, an international public policy and demographics firm. He is a Senior Fellow of the Center for Opportunity Urbanism (US), Senior Fellow for Housing Affordability and Municipal Policy for the Frontier Centre for Public Policy (Canada), and a member of the Board of Advisors of the Center for Demographics and Policy at Chapman University (California). He is co-author of the “Demographia International Housing Affordability Survey” and author of “Demographia World Urban Areas” and “War on the Dream: How Anti-Sprawl Policy Threatens the Quality of Life.” He was appointed to three terms on the Los Angeles County Transportation Commission, where he served with the leading city and county leadership as the only non-elected member. He served as a visiting professor at the Conservatoire National des Arts et Metiers, a national university in Paris.

Photo: City of San Francisco (by author)