More than a decade ago, the Sierra Club and I crossed keyboards over urban density. The Sierra Club had just posted a new "neighborhood consumption calculator," that gave visitors the opportunity to look at the purported impacts of various density levels. The Sierra Club designated 500 dwelling units per acre as "efficient urban." Independently, Randal O’Toole and I quickly were on the Internet pointing out the absurdity of such high density. I noted that the so-called "efficient urban" density was far higher than that of the "black hole" of Calcutta, and high enough for all US residents to live in the Portland urban area.

Within 24 hours of our responses, the "neighborhood consumption calendar" had been taken off the Internet. It was later to reappear with "efficient urban" density being discounted a full 80 percent, to 100 housing units per acre. This is still far more dense than nearly all of the world except for low income world shantytowns.

The Kolkata Municipal Corporation (KMC): The central city of Calcutta, now called Kolkata, remains one of the densest on earth. Its population density is 63,000 per square mile (24,000 per square kilometer) is nearly the same density as in Manhattan or the Ville de Paris. More accurately, it resembles the entire urban area densities of Mumbai and Hong Kong. The expanding suburbs of Kolkata have a population density of 25,000 per square mile (9,000 per square kilometer). The next edition of Demographia World Urban Areas (due out in the spring) will estimate the population density of the Kolkata urban area at 30,000 per square mile (12,000 per square kilometer).

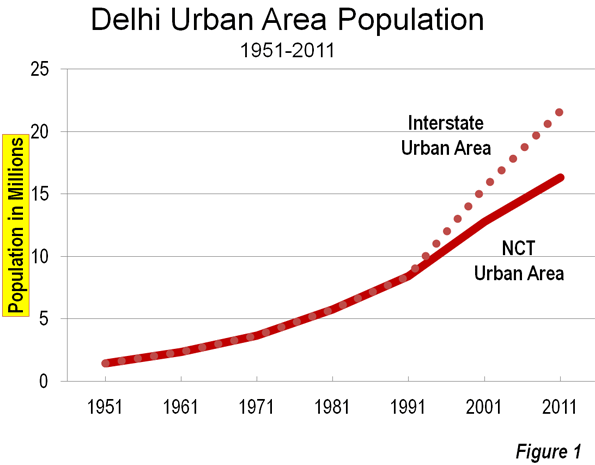

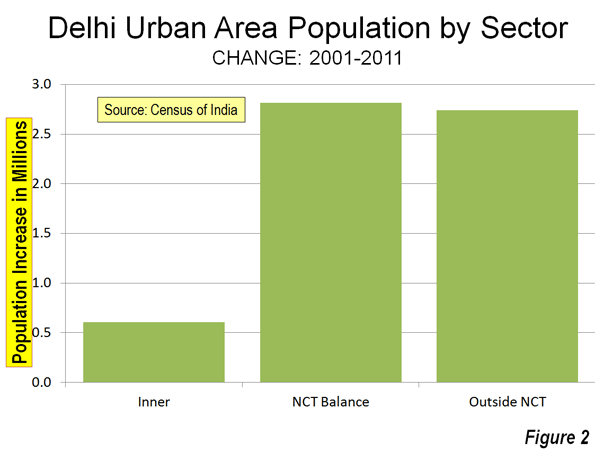

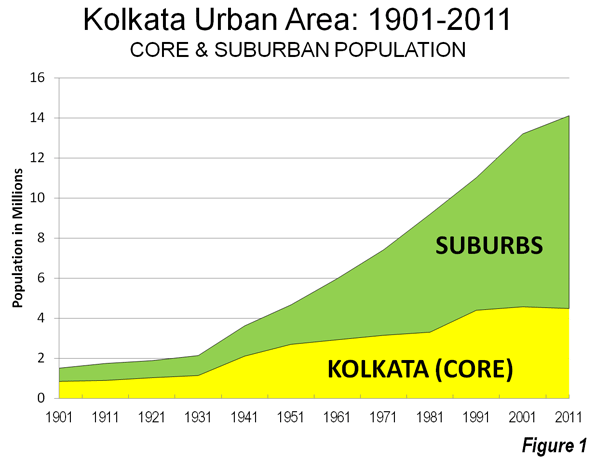

Kolkata’s spreading urbanization, however, has been going on for at least a half century. Since the 1951 Census, the central city of Kolkata has accounted for only 19% of the urban area population growth. The central city has added nearly 1,800,000 people while the suburbs have added approximately 7,650,000 (Figure 1).

Over the past two decades, the central city’s growth has been minimal, adding 87,000 people from 1991 to 2011, while the suburbs added more than 3 million new residents. This intensifies the pattern of the last half-century where most growth clustered close to the city core.

Between 1901 and 1951, 59% of the growth in the Kolkata urban area was in the central city (Kolkata lost the British capital to Delhi in 1911).

Photo: Victoria Memorial, KMC

Slower Growth in the Urban Area: Kolkata is an unusually shaped urban area, nearly 50 miles (80 kilometers) long and stretched along the Hooghly River, one of the many mouths of the Ganges. Dhaka, the megacity capital of Bangladesh used to be on a mouth, until the river’s course changed. The urban area averages little more than 10 miles (16 kilometers) in width. The municipality of Kolkata is in the south, on the east bank of the Hooghly, with most of the suburbs to the north or just across the river.

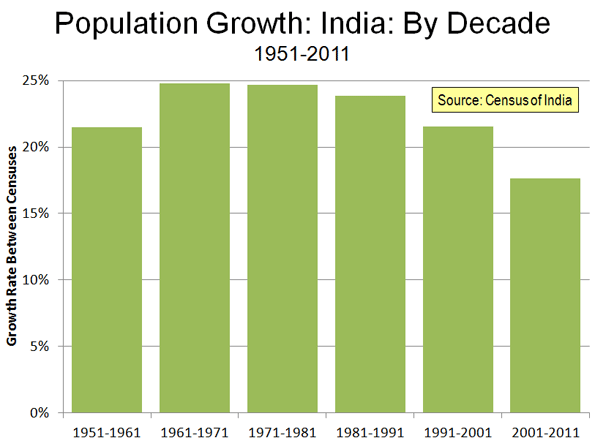

Like a number of major urban areas around the world, Kolkata has seen its population growth slow markedly. The peak population growth decade was the 1930s, when there was an increase of 69%. Growth dropped to 29% during the 1940s but continued at 20% or more until 2001. However, between 2001 and 2011, the urban area growth rate dropped to 7%, as the area added only 900,000 new residents. Despite its earlier, smaller size, the Kolkata urban area had not added this few people since the 1921 to 1931 decade.

In reality, Kolkata is getting less dense by the day. The results of the 2011 Census of India showed that every new resident of the Kolkata urban area was added in the suburbs (Note 1). Yes, the central city of Kolkata remains very dense but its population fell from 4,573,000 people in 2001 to 4,487,000 people in 2011. At the same time, the population of suburban Kolkata grew by nearly 1,000,000 people, and accounted for 110% of the population growth.

Photo: Howra Bridge, Hooghly River (Howra)

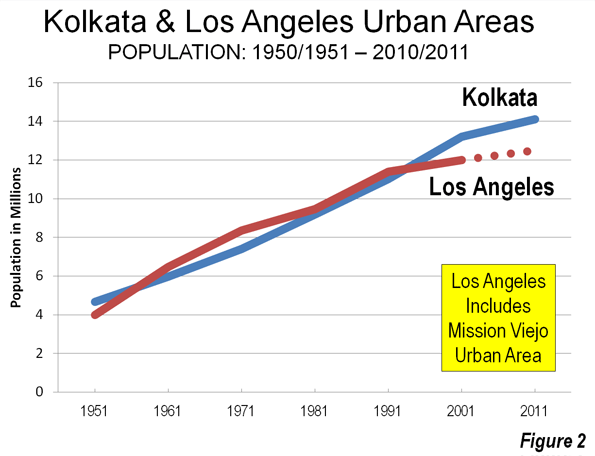

Kolkata, Los Angeles and China: It also may seem strange that despite its huge typically third world growth since 1951, the Kolkata urban area grew at a rate similar to that of the Los Angeles urban area (Note 2). Los Angeles was larger from the 1960s to 1990, while Kolkata was larger in the 1950s and has been larger the last two decades (Figure 2). Still, Kolkata’s growth has fallen to high income world rates. Other Asian megacities (over ten million) including Delhi, Shanghai, Beijing, Mumbai, Shenzhen, Manila, Jakarta, Dhaka and Guangzhou) have all experienced much faster growth over the past decade (Note 2). Shanghai and Beijing combined added nearly the same number of people as live in Kolkata.

Hyper-Densities: Nonetheless, Kolkata continues to have some of the highest densities in the world. In 2001, one third of the central city population (1.49 million) live in slums and shantytowns (photo). They are crammed into just 2 square miles (5 square miles). This would be like all the population of the San Fernando Valley living within a radius 0.6 miles (1 kilometer) of Los Angeles City Hall or all the population of the city of Dallas in the space covered by the passenger terminals at Dallas-Fort Worth International Airport. This is more than 725,000 people per square mile (280,000 per square kilometer), and would nearly equal the "efficient density" definition that the Sierra Club wisely discarded. It can only be hoped that when the 2011 Census slum data is available, it will show that all of the city of Kolkata’s population loss will have been from the slums.

Kolkata, like that of other large urban areas around the world described in The Evolving Urban Form series, shows that, given a chance, people reveal their preferences by moving to more space, to construct a better life for themselves and their households.

Photo: KMC Slum

Wendell Cox is a Visiting Professor, Conservatoire National des Arts et Metiers, Paris and the author of “War on the Dream: How Anti-Sprawl Policy Threatens the Quality of Life”

| Kolkata Urban Area: Population 1901-2011 | ||||||

| Year | Kolkata Municipal Corporation (KMC) | Suburbs | Kolkata Urban Area (Urban Aggolmeration) | KMC Share of Growth | KMC Growth | Suburban Growth |

| 1901 | 848,000 | 662,000 | 1,510,000 | 56.2% | ||

| 1911 | 896,000 | 849,000 | 1,745,000 | 51.3% | 5.7% | 28.2% |

| 1921 | 1,031,000 | 854,000 | 1,885,000 | 54.7% | 15.1% | 0.6% |

| 1931 | 1,141,000 | 998,000 | 2,139,000 | 53.3% | 10.7% | 16.9% |

| 1941 | 2,109,000 | 1,512,000 | 3,621,000 | 58.2% | 84.8% | 51.5% |

| 1951 | 2,698,000 | 1,972,000 | 4,670,000 | 57.8% | 27.9% | 30.4% |

| 1961 | 2,927,000 | 3,057,000 | 5,984,000 | 48.9% | 8.5% | 55.0% |

| 1971 | 3,149,000 | 4,271,000 | 7,420,000 | 42.4% | 7.6% | 39.7% |

| 1981 | 3,305,006 | 5,888,994 | 9,194,000 | 35.9% | 5.0% | 37.9% |

| 1991 | 4,400,000 | 6,622,000 | 11,022,000 | 39.9% | 33.1% | 12.4% |

| 2001 | 4,573,000 | 8,633,000 | 13,206,000 | 34.6% | 3.9% | 30.4% |

| 2011 | 4,487,000 | 9,626,000 | 14,113,000 | 31.8% | -1.9% | 11.5% |

—–

(Lead Photo: Mahatma Gandhi Road, KMC.

—–

Note 1: This is the Kolkata "urban agglomeration," which is the term the Census of India uses to denote urban areas, or areas of continuous urban development. The Census of India, however, applies to criteria to its urban area definitions that make them difficult to compare to urban areas in other parts of the world. The Census of India does not, for example, allow an urban agglomeration to be defined across state lines. Thus, the Delhi urban area continues to be shown as smaller then the Mumbai urban area. This is despite the fact that the immediately adjacent urbanization of Delhi includes millions of additional people in the states of Haryana and Uttar Pradesh and is by international definition by far the largest urban areas in India. The other difficulty is that the Census of India includes the entire land area of any municipality in the urban area. Thus, where municipalities are particularly large in area, as in the case of Mumbai, considerably more land area is reported that he is truly urban. This can lower urban area densities by the inclusion of large areas that are rural. In the case of the call, urban area, the municipalities are generally much smaller, and the geographical definition of the Census of India is much closer to a genuine definition of an urban area or urban agglomeration.

Note 2: The Mission Viejo urban area is included in the 2000 Los Angeles urban area population in this comparison. Much of this urban area was included in Los Angeles before the 2000 census and it seems likely that it will be reunited with Los Angeles in 2010. The 2010 US urban area geographical definitions have not yet been released. Based upon the change in the Los Angeles metropolitan area population, it is assumed that the Census Bureau’s urban area will show a population of approximately 12.5 million.

Note 3: Chongqing is sometimes incorrectly characterized as a megacity, because of its status of a "provincial level municipality" in China. However, the Chongqing provincial municipality is largely rural, and covers a land area similar to that of Austria or Indiana. The Chongqing urban area has a population of approximately 7 million.